No Place for Tajiks Here: How the EU is handing over refugees to the Rahmon regime over false accusations of ISIS links

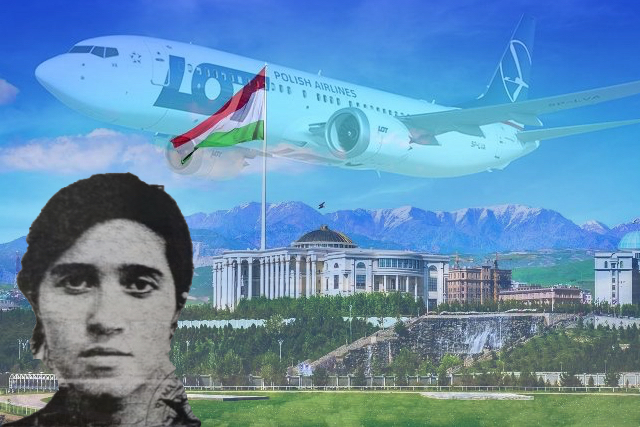

Belgian authorities are expected to make a decision soon regarding Tajik refugee Sitoramo Ibrokhimova. She will most likely be extradited to the Rahmon regime, as was her sister, 27-year-old Nigora Saidova, who was sent to Tajikistan along with her seven-month-old daughter on charges of aiding terrorism, which, according to The Insider, were fabricated. In her homeland, Saidova was sentenced to eight years in the worst women’s prison, where prisoners face rape and torture. Poland has been denying refugee status to Tajiks year after year — they are among the top three in terms of refusals, after Russians and Iraqi citizens. Emomali Rahmon uses the fear of ISIS to persecute entire families of emigrants – these can be both relatives of terrorists and relatives of oppositionists, but, as The Insider and the Polish weekly Polityka found out, European authorities do not really understand the case materials and often extradite citizens to Rahmon against whom the charges are obviously falsified. According to human rights activists, sometimes those forcibly returned are extradited to Russians: they are interrogated on the territory of the 201st military base near Dushanbe – tortured and forced to confess about ties to Ukraine.