Pour raconter son histoire, Fayçal prend ses précautions. Il n’accepte de parler qu’en-dehors de son quartier, dans un café discret. Le jeune homme n’a pas encore 30 ans. De forte corpulence, il a un visage doux et arbore un sourire gêné. Méfiant, il regarde constamment autour de lui. Après avoir passé plus d’un an en Syrie, il est retourné chez ses parents. Depuis, il ne sort presque plus de chez lui et se sent surveillé en permanence.

Pour raconter son histoire, Fayçal prend ses précautions. Il n’accepte de parler qu’en-dehors de son quartier, dans un café discret. Le jeune homme n’a pas encore 30 ans. De forte corpulence, il a un visage doux et arbore un sourire gêné. Méfiant, il regarde constamment autour de lui. Après avoir passé plus d’un an en Syrie, il est retourné chez ses parents. Depuis, il ne sort presque plus de chez lui et se sent surveillé en permanence.

Né au sein d’une famille assez aisée de la classe moyenne, Fayçal grandit dans un quartier populaire. Employé dans l’entreprise de ses parents, il est indépendant financièrement et a une vie stable.

Après la révolution, son “entourage” qu’il juge conservateur, l’incite à se tourner vers la religion. Il se met à fréquenter la mosquée du quartier et assiste aux “dourous”, des cours de théologie prodigués par l’imam. Comme dans les médias ou sur les réseaux sociaux, le conflit syrien y est constamment abordé et Fayçal commence à s’y intéresser. “Des femmes, des enfants massacrés, c’est impossible de rester insensible”, se souvient-il. “Beaucoup de jeunes sont partis, persuadés de devoir aider leurs frères sunnites”.

At a recent conference in Cologne on the future of Europe’s Muslims, Ali Erbaş, the head of Turkey’s state religious authority, the Diyanet, railed against what he called the “increase in anti-Islamic discourse and actions… [that] threaten European multiculturalism.”

At a recent conference in Cologne on the future of Europe’s Muslims, Ali Erbaş, the head of Turkey’s state religious authority, the Diyanet, railed against what he called the “increase in anti-Islamic discourse and actions… [that] threaten European multiculturalism.” Pour raconter son histoire, Fayçal prend ses précautions. Il n’accepte de parler qu’en-dehors de son quartier, dans un café discret. Le jeune homme n’a pas encore 30 ans. De forte corpulence, il a un visage doux et arbore un sourire gêné. Méfiant, il regarde constamment autour de lui. Après avoir passé plus d’un an en Syrie, il est retourné chez ses parents. Depuis, il ne sort presque plus de chez lui et se sent surveillé en permanence.

Pour raconter son histoire, Fayçal prend ses précautions. Il n’accepte de parler qu’en-dehors de son quartier, dans un café discret. Le jeune homme n’a pas encore 30 ans. De forte corpulence, il a un visage doux et arbore un sourire gêné. Méfiant, il regarde constamment autour de lui. Après avoir passé plus d’un an en Syrie, il est retourné chez ses parents. Depuis, il ne sort presque plus de chez lui et se sent surveillé en permanence. The Syrian jihad presented invaluable opportunities for

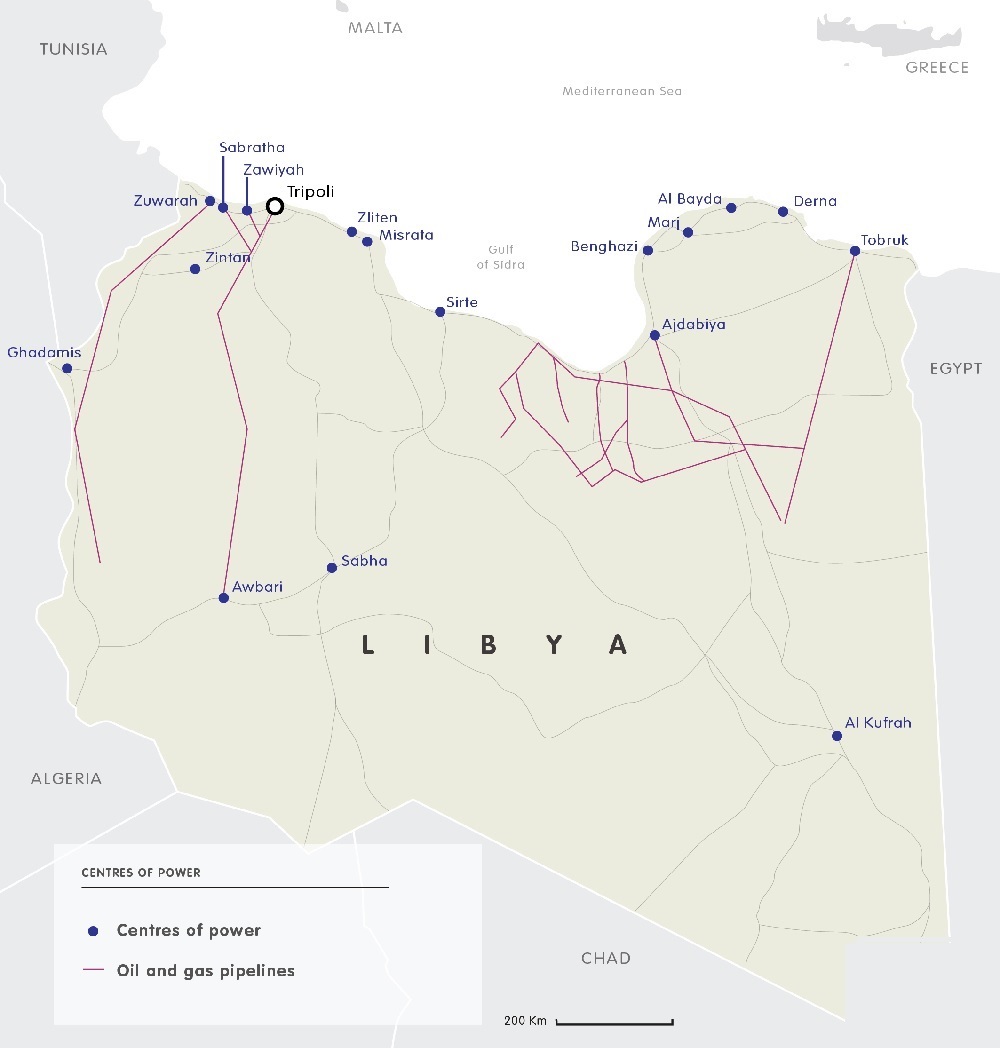

The Syrian jihad presented invaluable opportunities for Since the downfall of Muammar Gaddafi, a power vacuum has led Libya down a path of factionalism and war. Isolated from both Tobruk and Tripoli’s rule, extremists and separatists thrive, leaving the future of Libya hanging in the balance.

Since the downfall of Muammar Gaddafi, a power vacuum has led Libya down a path of factionalism and war. Isolated from both Tobruk and Tripoli’s rule, extremists and separatists thrive, leaving the future of Libya hanging in the balance.