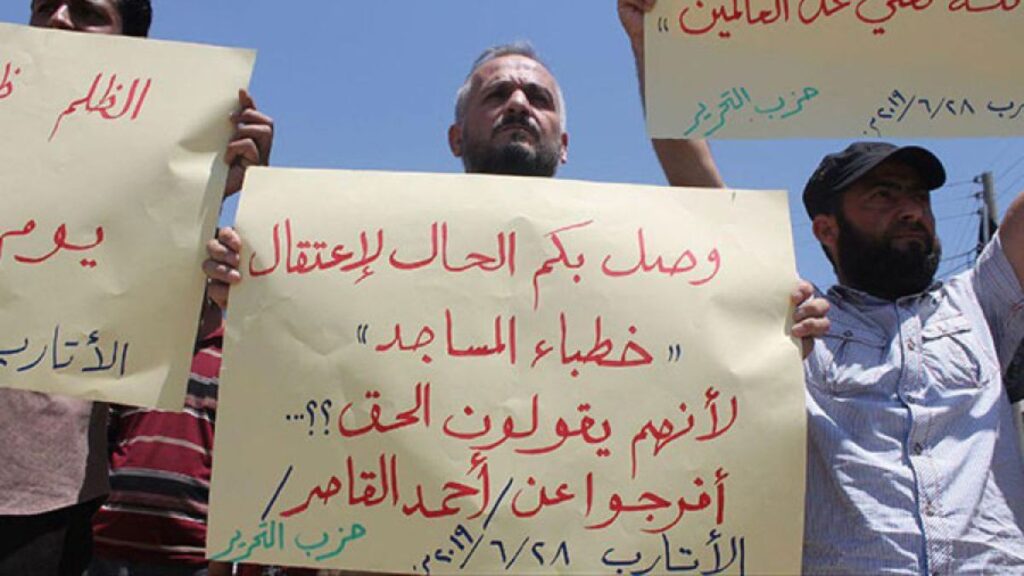

Idlib, Release of a Group of “Hizb ut Tahrir” Detainees

The Syrian government released a number of detainees affiliated with the Islamist-oriented Hizb ut-Tahrir party who had been imprisoned in Idlib (northwestern Syria) on Monday, February 16.

Abdo al-Dali, a member of the media office of Hizb ut-Tahrir, Wilayah Syria, confirmed to Enab Baladi that several party members detained in Idlib had been freed, most notably Ahmad Abdel Wahab, head of the party’s media office in Syria.