It’s going to be more difficult and a lot more dangerous for the Israeli Air Force to continue its frequent strikes against Iranian military assets in Syria.

The London-based Arabic language newspaper Asharq Al-Awsat reported on Saturday that Russia would be providing Syria with a higher-level anti-missile defense system than is currently deployed.

The report concludes that Moscow has “run out of patience with the Israeli strikes” and expects little or no blowback from the American administration. Russian President Vladimir Putin has been Syrian President Bashar Assad’s patron during years of civil war but has maintained a level of acceptance of former Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu’s constant attacks on Iranian arms and military equipment arriving in Syria.

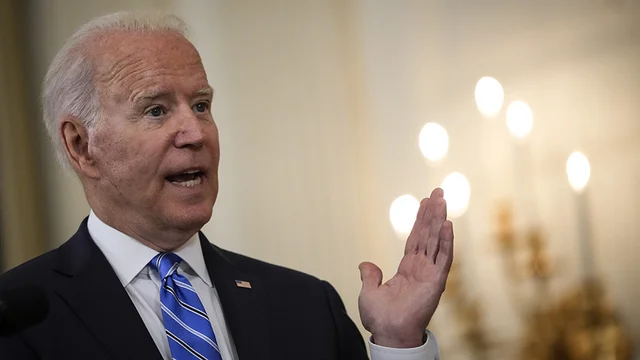

More than 100 strikes are estimated to have been launched by Jerusalem over the past year. There is an apparent re-evaluation underway by Putin regarding how far he is willing to allow Israel to go in the Syrian skies since the Biden and Bennett administrations have taken over.