The Warnings in Cold War History

Netflix viewers got an introduction, this spring, to a famous physics experiment: the three-body problem. A magnetized pendulum suspended above two fixed magnets will swing between them predictably. A third magnet, however, randomizes the motion, not because the laws of physics have been repealed, but because the forces involved are too intricate to measure. The only way to “model” them is to relate their history. That’s what Netflix did in dramatizing the Chinese writer Liu Cixin’s science-fiction classic, The Three-Body Problem: a planet light years from earth falls within the gravitational attraction of three suns. It’s no spoiler to say that the results, for earth, are not auspicious.

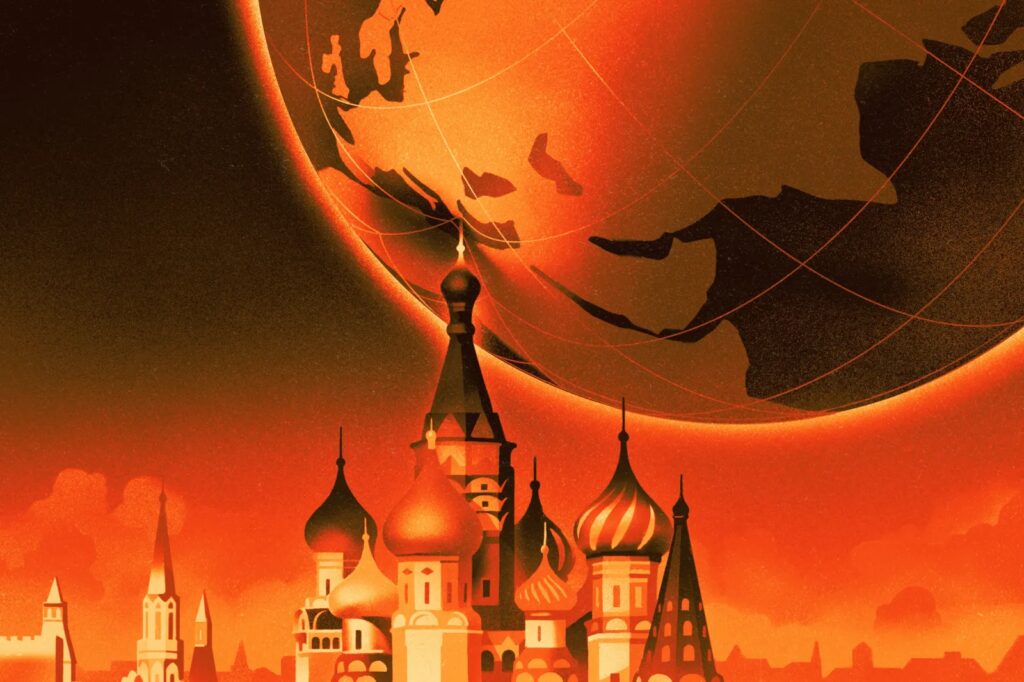

Sergey Radchenko, a historian at Johns Hopkins University, comes from the East Asian island of Sakhalin, a good place from which to detect geopolitical gravitations. His first book bore the appropriate title Two Suns in the Heavens: The Sino-Soviet Struggle for Supremacy, 1962–1967. His second, Unwanted Visionaries: The Soviet Failure in Asia at the End of the Cold War, extended his analysis through the 1980s. Now, with To Run the World: The Kremlin’s Cold War Bid for Global Power, Radchenko seeks to refocus recent scholarship, which has sought to “decenter” the history of that conflict, back on the superpowers for which it was originally known.

Previous accounts of the Soviet Union’s Cold War emphasized bipolarities: Marxist-Leninist ideology versus Russian nationalism in the “orthodox-revisionist” debates among historians half a century ago; then the revolution-versus-imperialism paradigm advanced by the expatriate scholars Vladislav Zubok and Constantine Pleshakov in the 1990s. “Decenterists” have since added a third polarity, contrasting the relative stability of the superpowers’ “long peace” with persistent violence among their surrogates elsewhere. Cold War history has therefore become, in this sense, its own three-body problem. How can we begin pulling it back together and, if possible, extract lessons for the future?

Theory, Radchenko acknowledges, won’t help: it privileges parsimony as a path to predictability but too often confirms what’s obvious while oversimplifying what’s not. That leaves, as an alternative, narration. But narration requires archives for validation, and access to archives seems unlikely in Vladimir Putin’s Russia, a regime not known for transparency.

History, however, is full of surprises. One is what Radchenko describes as a “deluge” of Cold War–era documents, released over the past decade, from Soviet government and Communist Party archives, as well as from the personal papers of Kremlin leaders. Radchenko doesn’t try to explain why this has happened; he’s content instead to make the most of the opportunity it presents to “know” Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Gorbachev, and their associates at a “very personal level.” It’s like being a “psychological counselor,” he writes, “in a session with a client who tells the same stories over and over again to reveal the underlying passions and fears.”

HOME AND AWAY

So what, from that vantage point, can one learn? Radchenko’s most significant finding is how great the gap was between the ideology on which the Soviet Union was founded, on the one hand, and the topography on which it sought to impose its authority, on the other. “What the Soviets saw as their ‘legitimate’ interests,” he writes, “were often not seen as particularly ‘legitimate’ by anybody else, leading to a kind of ontological insecurity on the Soviet part that was compensated for by hubris and aggression.”

Take, for example, Joseph Stalin’s simultaneous commitment to world revolution and to securing the state he ran. The Soviet Union, he believed, deserved a place of honor in international affairs as the first nation to have aligned itself with the class struggle, the previously hidden driver of modern history. Its security, however, required brutalities: agricultural collectivization, indiscriminate purges, exorbitant wartime sacrifices. The difficulty here, Radchenko points out, is that unilateral imposition secures neither honor nor safety: respect, if genuine, can arise only by consent. That left Stalin seeking to enhance the Soviet Union’s external reputation without compromising its internal safety while maintaining, in both domains, its and his own legitimacy. In short, a three-body problem.

Radchenko defines legitimacy as satisfaction with things as they are, and there are various ways of obtaining it. Marlon Brando, in The Godfather, spoke softly but left a horse head, when needed, on selected bedsheets: offers followed that recipients couldn’t refuse. Stalin was capable of such efficiencies, but only within realms he fully controlled. Beyond these, his preference was to convene bosses like mafia dons dividing up territories—hence his expectation at the World War II conferences in Tehran, Yalta, and Potsdam that his U.S. and British counterparts would acknowledge Soviet authority over half of Europe. But Stalin saw this, Radchenko argues, as only a temporary arrangement. The Anglo-Americans, being predatory capitalists, would soon go to war with one another, Stalin believed, leaving Europeans not yet within the Soviet sphere to voluntarily choose communist parties to lead them, in close correspondence with Moscow’s wishes.

When that didn’t happen—when Moscow’s legitimacy beyond Stalin’s authority failed to take root—he had only improvisation to fall back on: indecisiveness in responding to the Marshall Plan, a Czechoslovak coup that alarmed more than intimidated those who witnessed it, an unsuccessful blockade of Berlin from which he had to back down, and a botched campaign to displace Tito’s communist regime in Yugoslavia, the only one in Europe with homegrown legitimacy. That’s how the Soviet leader earned an honor he wouldn’t have wanted: he, more than anyone else, deserves recognition for having founded NATO in 1949. Legitimacy was the wild card, the disrupter, the third sun in the Stalinist Cold War firmament.

CALLING THEIR BLUFF

Stalin, a Europeanist, had no plans, Radchenko emphasizes, for “turning the world red.” Nikita Khrushchev was more ambitious. “National liberation” movements in Africa, Asia, and the Middle East would, he thought, look to the Soviet Union for leadership, if it could free itself from Stalinist repression while achieving more rapid economic development than capitalism had so far accomplished. Meanwhile, Mao Zedong’s establishment of a “people’s republic” in China more than compensated for communism’s setbacks in central and western Europe. Khrushchev wasn’t content, however, with these favorable portents. He wanted to speed things up, and that made him personally, in pursuit of his particular vision of legitimacy, his own wild card.

Khrushchev began the process with his 1956 “secret speech” denouncing Stalin to the 20th Party Congress. Because he’d failed to prepare anyone for it, the address became a “wound-up spring”—Radchenko’s apt characterization—which, when released, caused consternation at home; revolts in Poland and Hungary; disillusionment among French, Italian, and even Scandinavian communists; and deep distrust within the mind of Mao, who had only begun, with Stalin safely dead, to regard him as a role model. International communism did indeed go global, but in such a manner as to immediately fragment itself.

The successful Sputnik satellite launch of 1957 might have reversed these losses had Khrushchev not tried to make it a panacea. If the Soviet Union could send satellites into orbit, he reasoned, then why not refrigerators into kitchens? Why shouldn’t a socialist planned economy outproduce capitalist rivals in all respects?

Few goods of any kind appeared in communist households, however, a disappointment especially evident in East Germany, within which the postwar settlement had left the conspicuous capitalist enclave of West Berlin. Khrushchev tried resolving the situation with rockets: he would terminate Western rights in the city and enforce the restriction with threats of nuclear war. American spy planes and satellite photography, however, revealed that the Soviet military had not produced missiles “like sausages” as Khrushchev had unwisely bragged.

With his bluff called, Khrushchev allowed the East Germans the humiliation of a wall around West Berlin, then authorized the atmospheric test of an unusably gigantic thermonuclear bomb, and finally quietly—but not quietly enough—dispatched missiles armed with nuclear warheads to Fidel Castro’s Cuba, the only communist outpost in the Western Hemisphere, all in an effort to regain global respect by threatening global annihilation. Fed up with such risk-taking, Khrushchev’s Kremlin colleagues deposed him in October 1964, leaving Leonid Brezhnev to gradually consolidate the power he would hold longer than any Soviet leader apart from Stalin himself.

LEGITIMACY AND ITS DISCONTENTS

Brezhnev was stolid, soothing, and, until his health began to fail in the mid-1970s, reassuringly steady. That has faded him for most historians, who prefer writing about more colorful characters, but hints of revisionism have begun to appear: Zubok’s 2007 book, A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War From Stalin to Gorbachev, gives Brezhnev almost the status of U.S. President Richard Nixon, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, and West German Chancellor Willy Brandt as an architect of détente. How, though, could such an implied acceptance of international stability coexist with the expectation, which Brezhnev never repudiated, that “proletarians” in all countries would eventually rise up?

Through sharing legitimacies, Radchenko suggests, the most important of which was that the superpowers both feared a nuclear apocalypse. The Cold War didn’t end history, but it did remove whatever benefits might have remained in fighting another world war. Despite an overwhelming U.S. advantage in nuclear weapons at the time of the Cuban missile crisis, neither side was willing to risk using them against the other. Brezhnev’s role, through the rest of the 1960s, was to replace Khrushchev’s bluffs with actual capabilities, thereby creating a balance in strategic weaponry that made possible the arms limitation agreements of the 1970s. Quests for legitimacy, in this instance, converged compatibly.

A second convergence had to do with the demarcation of boundaries: Cold War competition would continue in some areas, but not in others. Brezhnev made it clear that the Soviet Union would still support “wars of national liberation” in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, while the Americans, less explicitly, committed themselves to waging what might be called “wars of containment” in those same regions. Meanwhile, the status quo that divided Europe would remain in place.

A third priority, for Brezhnev, was personal diplomacy. Khrushchev relished the recognition that came with his 1959 visit to the United States, but neither he nor Stalin tried to build long-term relationships with American or other Western leaders. Brezhnev, however, pursued Nixon almost as relentlessly as a stalker does a star, even as the president escalated military operations in Vietnam in 1972 and then sank into the Watergate swamps of 1973–74. Images of the two relaxing at Nixon’s San Clemente residence, admiring the Pacific while in shirtsleeves with feet propped up and drinks within reach, were a high point for Brezhnev, if not for the international proletarian revolution.

And yet legitimacies, Radchenko shows, could be a double-edged sword. Demarcations didn’t always diminish temptations, as when Nixon and Kissinger forced the Soviets out of the Middle East after the 1973 Yom Kippur War, or when Brezhnev took advantage, two years later, of the Americans’ defeat in Vietnam to expand Soviet activities in eastern and southern Africa. Third parties could upset equilibriums by switching sides, as the Chinese spectacularly did when they welcomed Nixon to Beijing in 1972, or by shaming superpower patrons for insufficient militancy, a proficiency the Cubans deployed against the Soviets in Africa in the years that followed.

Leadership, too, posed legitimacy problems. Presidential campaigns became permanent in the United States after Watergate, leaving little time and too much visibility for reflections, rectifications, and reassessments. Meanwhile, the absence of criticism and hence accountability in the Soviet Union required keeping Brezhnev in power until the day he died, a process hardly conducive to agility or adaptivity. These difficulties opened the way for Ronald Reagan, in his 1980 presidential campaign and during his first years in office, to question the legitimacy of the Cold War itself: if the purpose of détente had been not to end that conflict but to institutionalize it, was that the best that the competitors could do?

That brings Radchenko to the last Soviet leader, who so suspended himself between legitimacies that the end of his career coincided with the end of his country. Mikhail Gorbachev set out to reform his regime in such a way as to convince Europeans to welcome its membership among them, Americans to regard it as a partner in securing world order, and the world itself to acknowledge his own personal preeminence as, in Radchenko’s words, “strategist-in-chief for change.”

The first whiffs of perestroika, however, set off a “dash for the West” among former Soviet satellites, which saw far more clearly than Gorbachev that fulfilling his mission would mean their liberation. That withholding of legitimacy in his own neighborhood denied Gorbachev the much wider legitimacy he had hoped to obtain. Witnessing this, the non-Russian republics of the Soviet Union saw no reason themselves to remain within it, as ultimately, under Boris Yeltsin, did the Russian republic itself. Having delegitimized himself on all fronts, Gorbachev wound up, Radchenko somewhat rudely reminds us, making a Pizza Hut commercial in 1997. To be fair, he was the only Nobel Peace Prize winner to do so.

DISTANT MIRRORS

So is To Run the World, as Radchenko acknowledges in his introduction, “dangerously thin on theory”? For anyone in search of clockwork predictability, the answer is surely yes. But if one seeks patterns—the recognition of similarities across time, space, and scale—then this book has the potential to significantly revise not only how historians think about the Soviet Union but also the much longer sweep of Russian history that has now unexpectedly produced, in Putin, a new tsar.

For what Putin appears to want is a new legitimacy based on much older ones: not the ideological rigidities of Marxism-Leninism, but the murkier and more malleable legacies of tsarist imperialism, Russian nationalism, and an almost medieval religious orthodoxy. Where the Soviet Union fits within this frame—a post-Soviet history that echoes pre-Soviet history—remains to be determined, but by emphasizing legitimacy, Radchenko has pointed the way. “The sources of Soviet ambitions,” he concludes, “are not specifically Soviet but both precede and postdate the Soviet Union.” Putin’s ambitions aren’t likely to be much different.

Radchenko’s book challenges, as well, the study of grand strategy. That field has long loved binaries: ends versus means, aspirations versus capabilities, planning versus improvisation, hopes versus fears, even foxes versus hedgehogs. The unofficial motto of the Yale Grand Strategy program has long been F. Scott Fitzgerald’s claim that the sign of a first-rate intelligence is “the ability to hold two opposed ideas in the mind at the same time, and still retain the ability to function.” But what if it’s three?

The Cold War didn’t end history, but it did remove whatever benefits might have remained in fighting another world war.

What Radchenko shows is that the demands of revolution, security, and legitimacy were equally compelling for Soviet leaders during the Cold War. The first two they could balance with roughly predictable results, but not the third. For it lay beyond their remit: the “strong” were not always able to do what they wanted, to paraphrase Thucydides, and the “weak” found many ways to resist instruction, thereby retaining the right to decide things for themselves.

Should we conclude from this, then, that autocracies find retaining legitimacy more difficult than do democracies? It would be reassuring to think so, were it not for the particular questions lodged, like malevolent matryoshka dolls, within this larger one. How was it that ancient Athens, arguably the world’s first democracy, turned out to be its last for the next two millennia? Why did the American founders see themselves as establishing not a democracy but a republican empire? Didn’t the Americans, during the century named for them, also have, like the Soviet Union, an ideology they sought to export? How many recipients of instructions given then respect them now? And finally, do political processes within the United States reliably produce agile, adaptive leadership?

Good books, whatever their subject, provide mirrors in which we see ourselves, often with disconcerting results. To Run the World more than meets that standard. It’s not just a major reconsideration of Cold War history but also an admonition to any country—or to any ruler of a country—foolish enough to try turning its title into an agenda for action.