Russia is now in a far worse negotiating position than in 2014. Finding itself at the mercy of a monopsonist buyer, there is very little it can actually do.

A key topic of discussion during the Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s recent visit to Moscow was the Power of Siberia 2 gas pipeline project planned to export Russian natural gas from the Yamal Peninsula in Western Siberia to China. In the wake of the war in Ukraine and ensuing collapse of trade with Europe that has left Russia’s gas reserves stranded, the pipeline has taken on new importance and urgency. While the terms of the contract remain under negotiation and shrouded in secrecy, the future outlines of its pricing formula can be discerned from the existing Russian-Chinese gas contract: for the original Power of Siberia pipeline.

Gazprom has long touted the first Power of Siberia as a highly profitable and successful project—while going to great lengths not to disclose the actual parameters of ongoing trade. In June 2014, when the project was launched, the following figures were made public: Russia would sell China 38 billion cubic meters (bcm) of gas annually, totaling 1,000 bcm over a thirty-year contract, with an estimated sale price of $350 to $400 per 1,000 cubic meters.

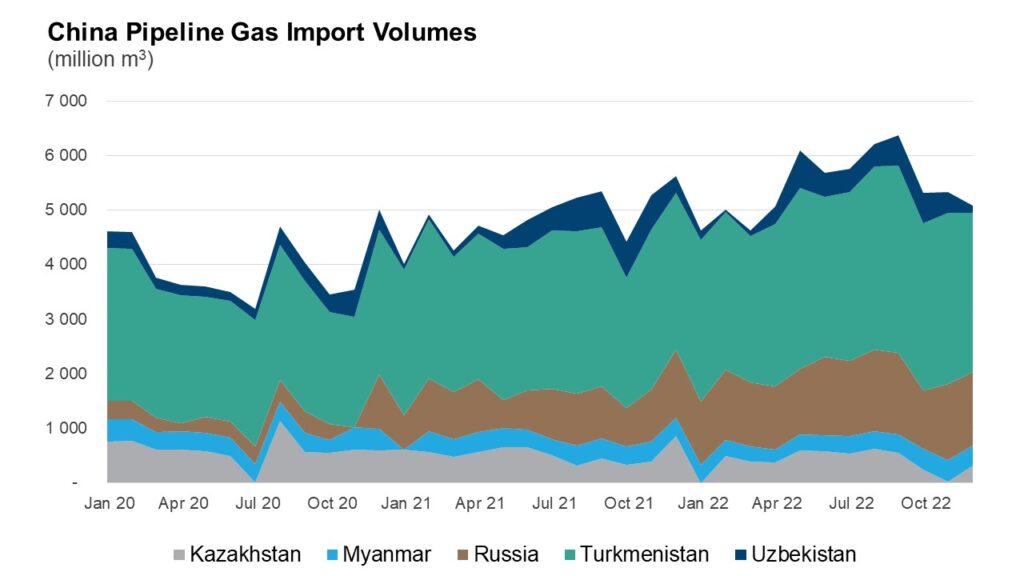

Gazprom has never disclosed the pricing formula, limiting itself to publishing annual sales volumes. Chinese customs authorities are also secretive about the parameters of their pipeline gas imports, and stopped publishing import volume data at the beginning of 2022. But China does still report monthly gas payment figures, and the data available for 2020–2021 are enough to make an educated guess on the structure of the contracts and compare China’s gas purchases from Turkmenistan, Myanmar, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Russia.

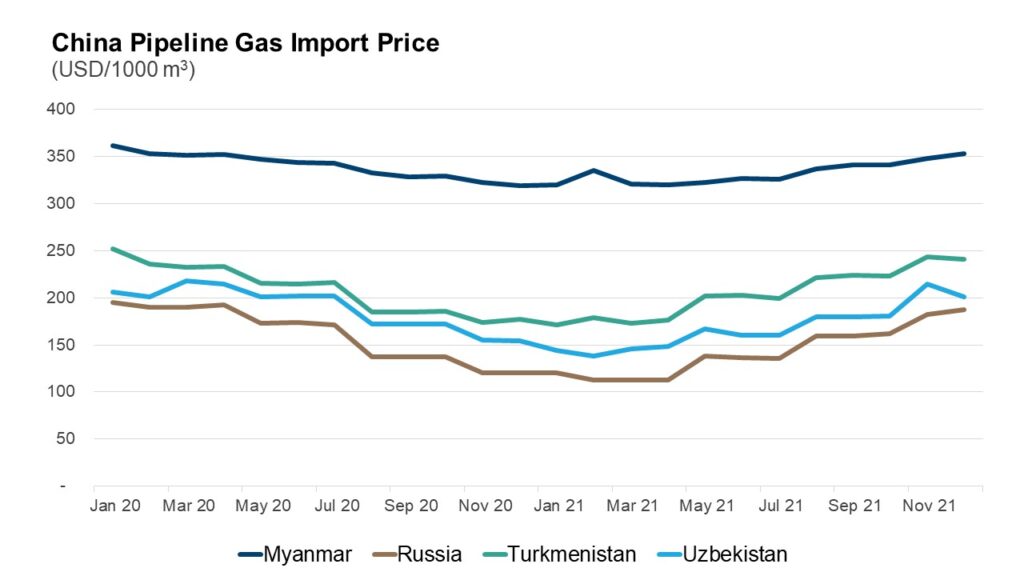

The chart above shows that Gazprom clearly got the worst deal among all of China’s pipeline suppliers. While the Myanmar contract, signed in the early 2000s for relatively small volumes, may not be a good reference point, comparison with the two Central Asian countries is more revealing. The price difference between the Russian and Turkmen contract is on average $55 per 1,000 cubic meters.

The discount in the Uzbek contract compared to Turkmenistan’s may be explained by geography: the pipeline originates in Turkmenistan and passes through Uzbekistan, picking up gas along the way, probably at a lower transportation tariff. But there are 2,150 kilometers of pipeline between Russia’s Chayanda field and the Chinese border, while Turkmenistan’s Galkynysh field is 1,830 kilometers from the Chinese border. The Power of Siberia enters China at Heihe in the industrial northeast, 500 kilometers from Harbin and 1,600 kilometers from Beijing, while the Central Asia–China pipeline crosses the border into Xinjiang, 3,000 kilometers from Beijing across the Gobi Desert, so the value of the gas at China’s western border should also be lower than in the northeast.

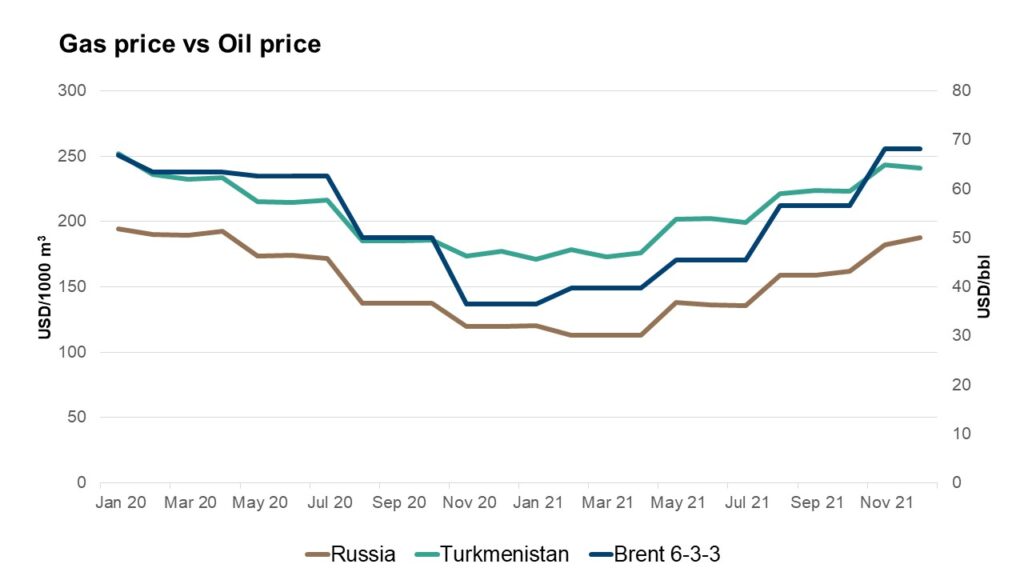

It is also obvious that the pricing for all the Chinese pipeline gas contracts is in parallel, most likely as a result of using the so-called 6-3-3 Brent average, meaning that the price is fixed for three months based on a six-month average with a three-month delay: i.e., the gas price for October–December is determined by averaging the oil price in January–June.

This observation makes it possible to derive a simple linear dependency for the formula in the Gazprom gas sales contract. The formula, at least for the observable price range, is:

GP=2.5*OP+20,

where GP is the gas price per 1,000 cubic meters, and OP is the Brent oil price per barrel on a 6-3-3 averaging basis. (Real regression coefficients are slightly different, but these are likely the round numbers stipulated in the contract.)

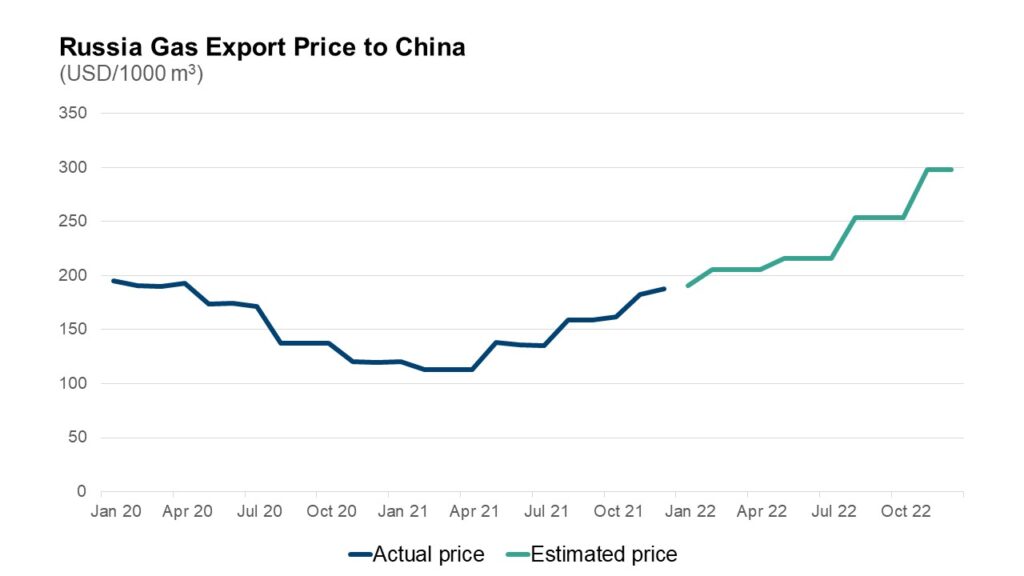

China has not reported volume data for 2022, but Russia has—on an annual basis only. Making a very simplistic assumption on the volume trajectory results in the following full price trajectory in 2020–2022.

There have been many unflattering comparisons between the prices that Russia managed to obtain from the European markets and the Chinese market. In general, these comparisons are not a perfect instrument, since gas markets are still compartmentalized. U.S. and Canadian producers sell their gas in North America at substantially lower prices than what American LNG fetches in Europe without being chastised for having subpar contracts for domestic sales. China is the only viable market for East Siberian gas, and as we have established, the Russian contract is in line with the rest of China’s gas import portfolio, albeit at a 15–20 percent discount.

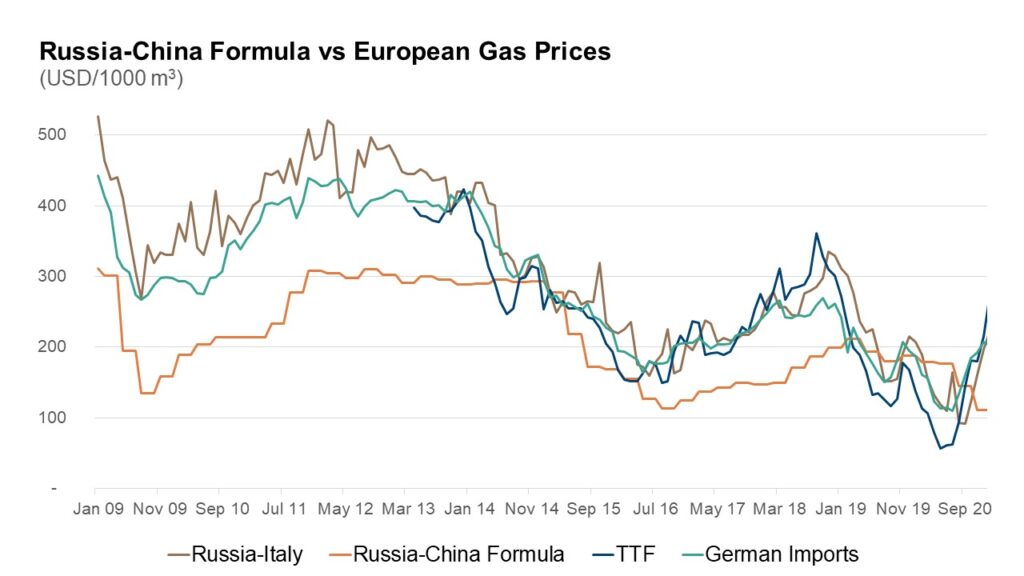

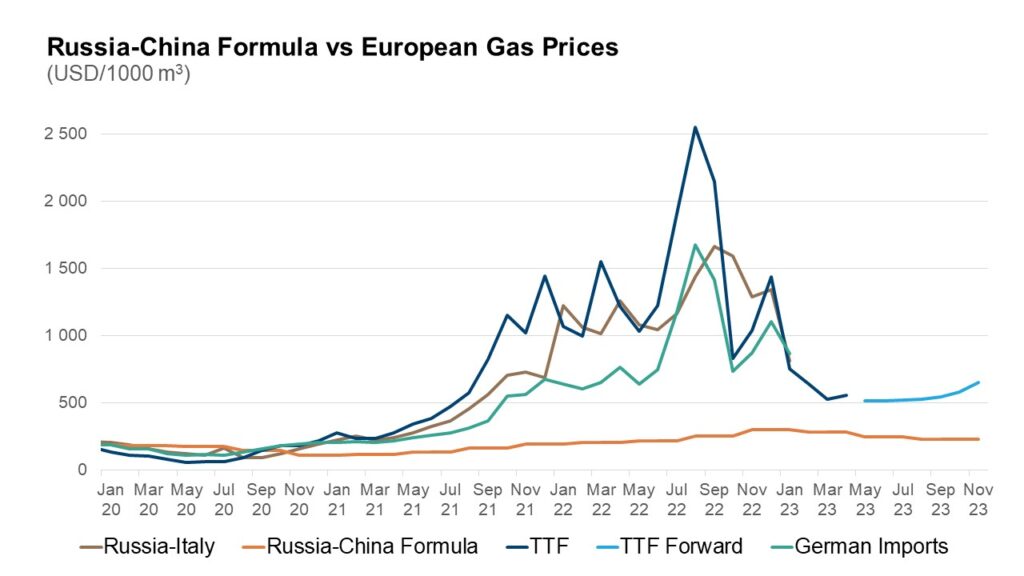

Still, it is interesting to compare the prices Russia was getting from the European market—for example, Russian sales to Italy, average German import prices, and European spot prices. It makes sense to run this comparison for two distinct periods: one until the end of 2020 (before the turmoil in the European gas markets), and the other from 2021 until today. The formulaic nature of the price in the Chinese contract—based on the oil price with a nine-month lag—makes it possible to predict the price of Russian gas exports to China and compare it with forward prices in Europe.

This picture offers a glimpse into the thinking of Gazprom executives back when the original Power of Siberia was being negotiated. In 2009–2014, oil prices ranged from around $30 per barrel to over $110. As we can see, in the late 2000s, gas prices in Europe were calculated on the same Brent 6-3-3 basis as the Chinese contract, but at a $150–200 per 1,000 cubic meters premium over the Russian-Chinese formula. By 2014, Gazprom was already under pressure to abandon the oil-linked pricing and shift to the European gas exchange link. That switch happened in 2016, and at the time of the signing of the Chinese contract, Gazprom’s management may well have felt that the price levels of the European contracts, based on parameters negotiated in the 1970s and 1980s in a very different market environment, were no longer sustainable and were ready for some concessions. Indeed, in the summer of 2014, when the oil price was in the triple digits, gas prices in Europe were already declining and the Chinese formula price was on par with European market prices.

The first half of 2014 was the last leg of the great oil price rally, but that only became obvious later on. In the summer of 2014, most price forecasts put the future oil price firmly above $100 per barrel. In an environment of high oil prices, oil-indexed contracts—even ones with mediocre parameters—would at least be on par with the spot market when compared to the Central Asian contracts. Gazprom executives apparently assumed that low prices were unlikely, and based their planning on a long-term oil price scenario of about $125 per barrel. Incidentally, when put into the Chinese contract formula, that estimate produces the $380 per 1,000 cubic meter price that was quoted by Gazprom’s leadership at the time of the contract’s signing. Clearly they were certain that the tide was rising, and it seemed more important to have a contract in place than to waste time trying to make it solid. The contract probably ended up being nowhere near as disastrous for Gazprom as some critics have suggested, but it’s certainly not lucrative.

Still, the oil-linked formula of averaging the price over long periods came in very useful during the COVID pandemic, when the Chinese market was much more profitable than Europe’s, and even falling oil prices in the same period did not change that. The European gas market turmoil, triggered first by extreme weather events around the globe and later amplified by Russia’s attempt to impose a gas blockade, changed this dynamic.

Oil-linked gas contracts created a safe haven for China amid an almost tenfold rise in gas prices in Europe and corresponding dynamics on the LNG markets. European gas prices have since climbed down from their peak, and for the rest of 2023 the forward market price is in the vicinity of $500, while the Chinese price will likely reach $300 before easing to $285. This is still higher than pre-pandemic prices of $200–250 for sales to Europe, but a far cry from the $380 proudly announced in 2014, even before we remember that $380 in 2014 dollars is equivalent to $470 in 2023.

A decade on, Russia and Gazprom might look at the lessons from the Power of Siberia 1 saga and resolve to be tougher in negotiations for the Power of Siberia 2. At the very least, Russia might try to draw a comparison with the pricing formulas for the Central Asian countries. Ultimately, however, a precedent has already been established, and Russia is now in a far worse negotiating position than in 2014. Finding itself at the mercy of a monopsonist buyer, there is very little it can actually do.