It was the kind of calling that Petr Jasek simply could not turn away from. For more than 28 years, the Czech Republic native and global ambassador for international nonprofit The Voice of the Martyrs (VOM) had traveled the world in support of persecuted Christians.

And then what was supposed to be a four-day trip to aid a badly beaten, young Christian convert in the Islam-dominant nation of Sudan in December 2015 turned into 445 days of torment and torture – and Jasek learned first hand what it felt like to be hunted and oppressed for his faith.

While preparing to board a flight home from the country’s capital Khartoum, the Christian leader was detained on charges of espionage and purporting to “wage war against the country of Sudan.” He was informed he was facing the death penalty and thrown into a filthy cell.

Although it was seemingly designed for just one person, Jasek was caged with six other cellmates – who he quickly learned were members of ISIS.

“They asked me to tell them some news from the outside world, and a few weeks earlier was the series of coordinated terrorist attacks across Paris,” Jasek, who has documented a haunting chronology of his experiences in a new book, “Imprisoned with ISIS: Faith in the Face of Evil,” told Fox News. “Then I heard the cheering, and I knew.”

The men, Jasek went on, were all young and “highly intelligent” – doctors, pharmacists and computer engineers – and were from an array of different countries, including Sudan, Pakistan, Egypt and Somalia. One fighter, in particular, was held in higher regard than the others. He was a Libyan national who had purportedly served as a personal bodyguard to Usama bin Laden in the barren hills of Tora Bora in the early days of the U.S. invasion in Afghanistan.

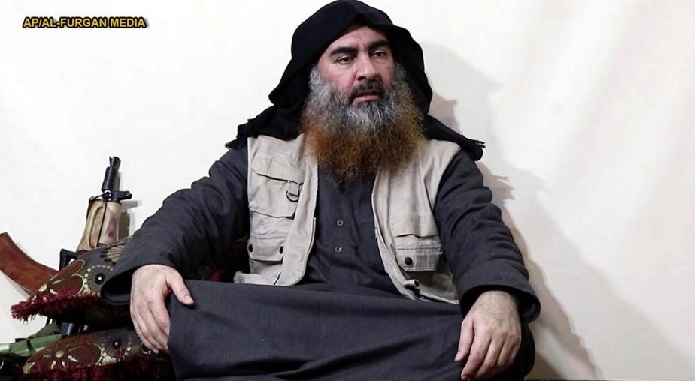

After being injured in a U.S. bomb blast and imprisoned after returning home to Libya, Jasek said, the jihadist was released by then ruler Muammar Gaddafi and went on to pledge allegiance to the notorious ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi before severing the heads of 21 Coptic Christians on the Libyan shores in February 2015. The fellow inmates lauded the Libyan as “the man of the sword,” whose hands were still figuratively saturated in the blood of the nonbelievers.

But the initial curiosity the ISIS terrorists had toward their new devoutly Christian cellmate quickly gave way to brutality and beatings.

“They started to treat me as an infidel, calling me a filthy rat and a filthy pig. I was not allowed to move on my own; they forced me to answer their questions,” Jasek recalled. “Then started the physical attacks – fists to my face, kicking my legs with their shoes still on. They used a wooden stick to beat me and experimented with other modes of torture.”

At one point, Jasek’s body was forced into such arduous positions for extended periods that he was not even able to walk for days on end. The sound of laughter from the guards echoed through the iron bars and constantly swirled in his mind.

“The guards were allowing them (the ISIS members) to have more freedom in prison than any of the others because they were afraid of them,” Jasek explained. “It makes you question who the real prisoners are.”

As the men prayed loudly around him at least five times per day and read from their Korans, the Czech native – who was not permitted so much as a Bible – turned his Christian prayers inward and did whatever he could to hold on to the remaining threads of his sanity.

“I was concerned I would lose my sane mind,” Jasek admitted. “Worse than the living conditions, the infectious diseases, and the worry of losing my life, I was trying to occupy my mind to something that made sense.”

He could not, he would not, fall apart, he pledged silently.

On one especially grim day, after months of merciless treatment at the hands of ISIS, as his body broke down and he suffered from malnutrition, the ISIS operatives decided Jasek should be waterboarded and demanded relocation to the only cell with a running tap. Just before the process was about to begin, the Christian leader was whisked away by a guard and into the dearth of solitary confinement.

“You would think these people would be punished, but actually, I was the one punished,” he said.

In the solitary cell, where there were no cracks of light, Jasek was left to endure another torture method dubbed “the freezer,” whereby freezing air was haphazardously blown in to bite his feeble frame.

The sobering nights and days dragged on, and Jasek was relocated to several other prisons – some overstuffed with the sick and diseased, teeming with insects and overflowing sewage. He had little more than scraps of moldy bread to eat and dozens fought over the meager rations to temporarily ease their hunger pains.

His case was finally brought before Sudan’s Court of Law in early February 2016.

“In one sense, it was a tragic comedy,” Jasek noted, detailing how it is all the worst kept secret that the judge was merely an arm of then-President Omar Bashir’s secret police. “I was sentenced to life imprisonment.”

As it stands, Sudan is ranked the seventh worst country for the persecution of Christians, according to global watchdog Open Doors.

And although Jasek knew deep down that Christians across the world were praying for him and diplomats spanning Europe and beyond were advocating for his release, the ruling gave him a new lease on life.

In a musty cell converted into a makeshift chapel, Jasek resumed his passion for preaching to fellow prisoners, the ones who had fallen through the cracks of society.

“Once, sometimes twice a week, I would preach to the hopeless, the desperate, and the forgotten prisoners. I knew we were being monitored, but I had nothing left to lose. I had already been sentenced to life imprisonment so there could be no more penalty on me,” Jasek said. “I saw the way their lives transformed through the gospel, and that was the most important mission of my life.”

Suddenly, one morning in the spring of 2017, 445 days after he was cuffed and dragged from Khartoum’s airport, the heavy prison cell door was wrenched open and the guards told him he was to be released.

The behind-the-scenes negotiations had finally come to fruition. And although Jasek walked away from those decrepit confines and never looked back, he returned home with a profound sense of clarity and understanding that the path of persecution was one he had been destined to travel.

“Persecution was to be expected because that is what Jesus had been preparing his followers for all along, so having this mindset helped me to overcome throughout this time,” Jasek added. “I prayed a lot, and I knew that my life was not in my own hands. This strength came not from myself, but the strength came from Lord Jesus.”