Hamas, or the Islamic Resistance Movement, is a Palestinian Islamist military and sociopolitical movement that grew out of the Muslim Brotherhood, a Sunni religious and political organization founded in Egypt in 1928 that has branches throughout the world.10 Hamas emerged in Gaza in the late 1980s, and established itself as an alternative to the secular Fatah movement in the 1990s by violently attacking Israeli targets after Fatah had entered into a peace process with Israel. Over time, Hamas has attacked or repressed Palestinian political and factional opponents.

After Israel withdrew military forces from Gaza in 2005, Hamas forcibly seized the territory from the Fatah-controlled Palestinian Authority (PA) in 2007. Hamas has both political and military components and exercises de facto government authority and manages service provision in Gaza. Hamas controls Gaza through its security forces and obtains resources from smuggling, informal “taxes,” and reported external assistance. According to the U.S. State Department, “Hamas has received funding, weapons, and training from Iran and raises funds in Persian Gulf countries. The group receives donations from some Palestinians and other expatriates as well as from its own charity organizations.”11 One media report has suggested that during this decade, Hamas has received some of its funding in cryptocurrency.12

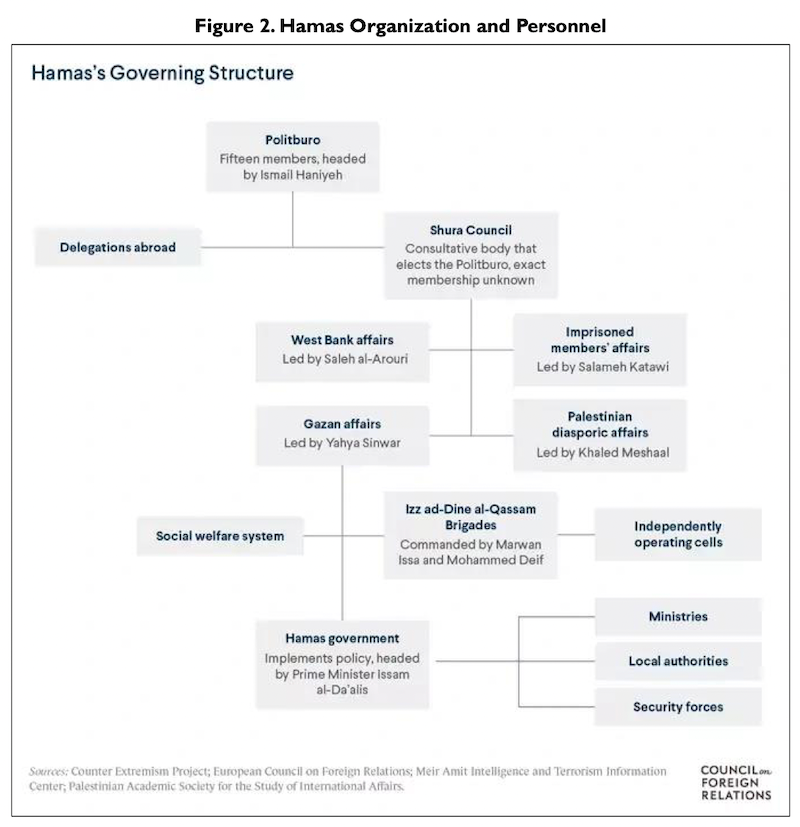

Yahya Sinwar, Hamas’s leader for Gaza, came from Hamas’s military wing (see below). Aside from those living in Gaza and the West Bank, some Hamas leaders and personnel may live in Arab countries and Turkey. Hamas’s political bureau leader, Ismail Haniyeh, appears to be based in Doha, Qatar.

Hamas and other Gaza-based militants have engaged in occasional conflict with Israel since Hamas seized Gaza by force in 2007. During the major conflicts in 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, and 2021, Hamas and other militants launched rockets indiscriminately toward Israel, and Israeli military strikes largely decimated Gaza’s infrastructure.

Since 2007, Gaza has faced crisis-level economic and humanitarian conditions, partly owing to broad restrictions that Israel and Egypt—citing security concerns—have imposed on the transit of people and goods. Gazans face chronic economic difficulties and shortages of electricity and safe drinking water.13 Because Gaza does not have a self-sufficient economy, external assistance largely sustains humanitarian welfare. Egypt and Qatar helped mediate conflict and provided basic resources in the wake of the four past major conflicts, but Gaza has not experienced broader economic recovery or reconstruction.

Hamas’s military wing, the Izz al Din al Qassam Brigades,14 has killed hundreds of Israelis15 and more than two dozen U.S. citizens (including some dual U.S.-Israeli citizens)16 in attacks since 1993. As the Qassam Brigades developed from a small band of guerrillas into a more sophisticated organization with access to greater resources and territorial control, its methods of attack evolved from small-scale kidnappings and killings of Israeli military personnel to suicide bombings and rocket attacks against Israeli civilians. The planning, preparation, and implementation of the October 7, 2023, attacks in Israel apparently demonstrate a further evolution in the Qassam Brigades’ capabilities, including the use of drone munitions, personnel- capable gliders, and complex infantry operations featuring thousands of personnel attacking across Israeli-controlled lines along multiple axes.

Hamas’s ideology combines Palestinian nationalism with Islamic fundamentalism. Hamas’s founding charter committed the group to the destruction of Israel and the establishment of an Islamic state in all of historic Palestine.17 A 2017 document updated Hamas’s founding principles. It stated that Hamas sees its conflict as being with the “Zionist project,” rather than Jews in general, and expressed willingness to accept a Palestinian state within the 1949/50-1967 armistice lines if it results from “national consensus,” while rejecting Zionism completely and stating Hamas’s preference for the establishment of an Islamist Palestinian state from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea and from the southern Israeli city of Eilat to the Lebanese border.18 (For background on the history of Arab-Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian conflict, see Appendix B in CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti.)

Having consolidated control over Gaza, and pursuing popular support through armed attacks on Israel, Hamas has appeared to seek to compete politically with other Palestinian movements or establish its indispensability to a future negotiated Israeli-Palestinian political arrangement. Hamas’s 2017 document states that the group remains open to democratic political competition with Palestinian rivals, but underscores goals incompatible with recent Arab-Israeli normalization diplomacy. Elections have not occurred in Gaza since 2007, and Hamas appears to maintain strict control over political activity in areas under its control. Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have documented Hamas human rights violations against Palestinian civilians and violence against Israelis.

Foreign terrorist organization designation and consequences19

The U.S. government designated Hamas as a foreign terrorist organization (FTO) on October 8, 1997. (The Iran-backed Shia Islamist group Lebanese Hezbollah (or Hizballah) was designated as an FTO on the same date.) The State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism (CT) is responsible for identifying entities for designation as an FTO. Prior to doing so, the Department is obligated to demonstrate that the entity in question engages in “terrorist activity” or retains the capability and intent to engage in terrorist activity or terrorism.20 When assessing entities for possible designation, the CT Bureau looks not only at the actual terrorist attacks that a group has carried out, but also at whether the group has engaged in planning and preparations for possible future acts of terrorism or retains the capability and intent to carry out such acts.

Entities placed on the FTO list are suspected of engaging in terrorism-related activities. By designating an entity as an FTO, the United States seeks to limit the group’s financial, property, and travel interests. Per Section 219 of the INA, as amended by Section 302 of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-132), the Secretary of State must demonstrate that the entity of concern has met the three criteria to allow the Department to designate it as an FTO. The suspected terrorist group must:

be a foreign organization,

engage in or retain the capability and intent to engage in terrorism, and

threaten the security of U.S. nationals or the national defense, foreign relations, or the economic interests of the United States.

In general, the designation of an entity, such as Hamas, as an FTO leads or may lead to the following consequences:

It is unlawful for a person in the United States or subject to the jurisdiction of the United States to knowingly provide “material support or resources” to a designated FTO.

Representatives and members of a designated FTO, if they are aliens, are inadmissible to, and in certain circumstances removable from, the United States.

The Secretary of the Treasury may require U.S. financial institutions possessing or controlling any assets of a designated FTO to block all transactions involving those assets.

May motivate efforts by the U.S. government and other nations to curb terrorism financing.

May stigmatize and isolate the FTO outside of its established support base.

May deter donations or contributions to and economic transactions with the FTO.

May heighten public awareness and knowledge of the FTO and terrorist organizations more generally.

May signal to other governments U.S. concern about designated organizations.

Hamas’s relationship with Iran

The Iranian government has supported Hamas for decades, going back nearly to the group’s inception.21 Iranian officials met with Hamas leaders and expressed public backing for the group and its goals beginning in the early 1990s, as Hamas sought to take up the mantle of Palestinian resistance to Israel against the backdrop of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO)-Israel negotiations that culminated in the 1993 Oslo Accord.22 Hamas opened an external office in Iran in 1992.

It is less clear how much material support the Iranian government provided to Hamas in the first years of the relationship. In 1998, Hamas’s spiritual leader Ahmad Yassin (later killed in a 2004 Israeli strike) reportedly obtained from Iran a pledge of $15 million a month.23 Hamas leaders gave conflicting accounts of their ties with Iran throughout the 1990s, perhaps sensitive to Palestinian domestic criticisms of Hamas as being reliant on foreign sponsors.24

During the second Palestinian intifada (or uprising) of 2000-2005, Iran reportedly continued to provide support to Hamas, including via the Shia Islamist group Lebanese Hezbollah (also an FTO).25 Some have contrasted Iran’s relationship with Hezbollah (a “full Iranian proxy,” in the words of one observer) with its relationship with Hamas (“a pragmatic partner to Iran’s anti-Israel axis”).26

Since Hamas took over de facto control of the Gaza Strip in 2007, it has engaged in several rounds of conflict with Israel, with continued reported material and financial support, but uncertain direction, from Iran. Iranian aid has been especially important to Hamas in light of Israeli-Egyptian restrictions in place for Gaza since 2007 on the transit of people and goods, and with regard to Hamas’s arsenal of rockets, which have featured prominently in Hamas attacks against Israel for years. Iran initially smuggled rockets into Gaza by sea and via illicit tunnels under the Egyptian border. After Egypt began cracking down on those tunnels in 2013, and as ties between Iran and Sudan (a key arms transit point) began to deteriorate in 2014, Iran focused more on teaching Palestinian militants how to use Iranian systems and locally manufacture their own variants.27

Iran-Hamas relations deteriorated after the outbreak of violence in Syria in 2011, with Iran and Hezbollah backing the government of Bashar al Asad, and Hamas siding with the mostly Sunni opposition. In 2012, Hamas’s political leadership left Damascus for Qatar, where it has reportedly been based since then. In 2017, with Hamas more isolated regionally and with the Iran-backed Asad government ascendant, the two sides began to repair ties and have since appeared closely aligned. Hamas’s top political leader, Ismail Haniyeh, reportedly visited Tehran at least three times between 2019 and the October 7 attacks.28

The level of Iranian material support for Hamas has reportedly remained high in recent years. In a September 2020 publication, the State Department reported that “Iran historically provided up to $100 million annually in combined support to Palestinian terrorist groups, including Hamas, Palestine Islamic Jihad (PIJ), and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command.”29 Haniyeh reportedly said in a January 2022 interview that Iran was the “main funder” of a $70 million “plan of defense for Gaza” after 2009.30

Hamas attacks: Why and why now?

Hamas leaders have said that their planning and preparation for the October 2023 attacks took place over several years, suggesting that the group made a strategic decision to prepare itself to be able to carry out attacks and operations that might change the status quo and prevailing assumptions in the group’s long confrontation with Israel.31 The decision to launch the attacks in October 2023 may reflect various Hamas motivating factors, including:

Disrupting Arab-Israeli normalization efforts – The October 7 attacks may have been intended to disrupt existing and potential future normalization agreements between Israel and Arab states, including U.S.-backed efforts to promote Saudi-Israeli normalization.

Seeking to strengthen its domestic position – Hamas may have launched the attacks in a bid to bolster its domestic political position vis-à-vis the struggling Palestinian Authority (PA) and its president since 2005, Mahmoud Abbas. Difficult and deteriorating living conditions in Gaza may have increased local political pressure on Hamas, and Hamas leaders may have perceived political opportunity arising from a pattern of confrontations in 2022 and 2023 between Israelis and Palestinians in the West Bank and in Jerusalem. A former senior U.S. official has speculated, “

Capitalizing on Israeli domestic turmoil – Political tensions have risen in 2023 among Israelis, stemming from disputes over proposed judicial reform and other issues. Hamas and its allies may have perceived an opportunity to amplify discord among Israelis by launching the attacks and successfully targeting Israeli military and civilian targets.

Using hostages for prisoner releases or other concessions – Hamas leaders have long highlighted the release of Palestinian prisoners held by Israel as a priority for the group, and may have launched the attacks to use hostages to obtain prisoner releases or other Israeli concessions.

Notes:

10 U.S. State Department, Country Reports on Terrorism, 2021, released February 2023.

11 Ibid.

12 Angus Berwick and Ian Talley, “Hamas Militants Behind Israel Attack Raised Millions in Crypto,” Wall Street Journal, October 10, 2023.

13 For information on the situation, see U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory (OCHA-oPt), Gaza Strip: Critical Humanitarian Indicators, https://www.ochaopt.org/page/gaza-strip-critical- humanitarian-indicators.

14 Izz al Din al Qassam was a Muslim Brotherhood member, preacher, and leader of an anti-Zionist and anti-colonialist resistance movement in historic Palestine during the British Mandate period. He was killed by British forces in 1935.

15 Figures sourced from Jewish Virtual Library website at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Terrorism/TerrorAttacks.html and https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/comprehensive-listing-of-terrorism-victims-in-israel. In the aggregate, other Palestinian militant groups (such as Palestine Islamic Jihad, the Fatah-affiliated Al Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) also have killed scores, if not hundreds, of Israelis since 1993.

16 Figures sourced from Jewish Virtual Library website at http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Terrorism/usvictims.html.

17 For an English translation of the 1988 Hamas charter, see http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/hamas.asp.

18 “Hamas in 2017: The document in full,” Middle East Eye, May 1, 2017. This document, unlike the 1988 charter, does not identify Hamas with the Muslim Brotherhood.

19 Prepared by John Rollins, Specialist in Terrorism and National Security. For more information, see CRS In Focus IF10613, Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), by John W. Rollins.

20 As defined in Section 212 (a)(3)(B) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) (8 U.S.C. §1182(a)(3)(B)), or “terrorism,” as defined in Section 140(d)(2) of the Foreign Relations Authorization Act (FRAA), Fiscal Years 1988 and 1989 (FRAA) (22 U.S.C. §2656f(d)(2)).

21 The Iranian government has backed terrorist groups since the early 1980s, focused initially on supporting the Shia

Islamist group Hezbollah in Lebanon and pressuring Persian Gulf monarchies to cease their support for Iraq in its war against Iran. After the first Palestinian intifada (or uprising) broke out in 1987 (the same year Hamas was founded), Iran began to focus more on supporting Palestinian groups. See U.S. State Department, Patterns of Global Terrorism: 1986, January 1988 and Patterns of Global Terrorism: 1989, April 1990.

22 “Iran pledges to aid Hamas in fight for ‘free Palestine,’” Independent (London), November 17, 1992; Christopher Walker, “PLO fears rise of fundamentalists,” Times (London), December 18, 1992; “Iran tells Hamas it is firmly against PLO peace deal,” Reuters, November 30, 1993. For background on the Oslo Accord, see CRS Report RL34074, The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations, by Jim Zanotti.

23 Laura King, “Hamas leader gaining Arab support,” Associated Press, May 27, 1998.

24 See, for example, “Hamas leader Yasin interviewed on attacks on civilians, ties with Iran,” BBC Monitoring, October 16, 1999.

25 Aaron Mannes, “Iran binds Hizballah to Hamas,” Jerusalem Post, March 30, 2004.

26 Ido Levy, “How Iran fuels Hamas terrorism,” Washington Institute for Near East Policy, June 1, 2021.

27 Fabian Hinz, “Iran transfers rockets to Palestinian groups,” Wilson Center, May 19, 2021; Adnan Abu Amer, “Report outlines how Iran smuggles arms to Hamas,” Al-Monitor, April 9, 2021.

28 Maren Koss, “Flexible resistance: How Hezbollah and Hamas are mending ties,” Carnegie Middle East Center, July 1, 2018. Haniyeh reportedly visited Tehran in June 2019, January 2020 (for Soleimani’s funeral), and August 2021 (for Raisi’s inauguration). Iran and Sudan announced the resumption of diplomatic relations on October 9, 2023.

29 U.S. State Department, Outlaw Regime: A Chronicle of Iran’s Destructive Activities, September 2020.

30 Mai Abu Hasaneen, “Hamas holds memorial tribute for Soleimani in Gaza,” Al-Monitor, January 7, 2022.

31 Hamas official Ali Baraka quoted in Samia Nakhoul and Laila Bassam, “Who is Mohammed Deif, the Hamas commander behind the attack on Israel?” Reuters, October 11, 2023.

32 Martin Indyk, “Why Hamas Attacked—and Why Israel Was Taken by Surprise,” Foreign Affairs, October 7, 2023.