As the U.S. prepares to withdraw from Afghanistan, China seeks to leverage opportunities for influence while avoiding potential security risks.

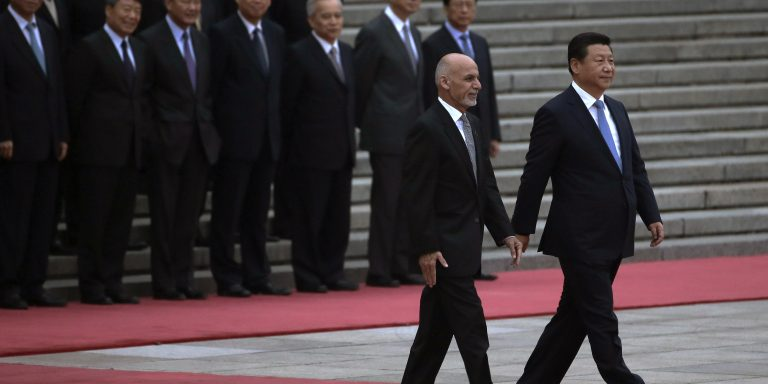

In early June, foreign ministers from China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan met to discuss how to maintain security amidst a U.S. troop withdrawal.

China’s growing visibility in the region means Beijing could find its diplomats and assets being targeted by terrorists more frequently

China increasingly views the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan through the lens of great power competition, rather than a solely regional matter.

As the United States prepares to withdraw from Afghanistan, countries in the region are tailoring their respective strategies to take advantage of the resulting power vacuum. Beijing has been preparing for this scenario, conducting outreach and steadily improving relations with the various Afghan actors, including the Taliban, in anticipation of this inevitability and to secure its political, security, and economic interests. China has touted its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and strengthened cooperation with Pakistan through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), featuring investment in the Gwadar port. China has portrayed the BRI as a solution to both instability and underdevelopment, arguing that by linking Afghanistan with Pakistani sea ports it will help promote Afghanistan’s development and offer new economic opportunities. A Chinese-funded project near Kabul seeks to create one of the largest copper mines in the world. China has myriad other economic interests in Afghanistan, projects which could be derailed by spiraling violence that spills over into neighboring countries. Moreover, it retains a watchful eye on the impact of events in Afghanistan on the Uyghur community in the region.

In early June, foreign ministers from China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan met to discuss how to maintain security amidst a U.S. troop withdrawal, which China has openly criticized. Their meeting stressed the importance of preventing an upsurge in terrorism that could have second order effects beyond Afghanistan’s borders. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi spoke at length about the need to “strengthen communication and cooperation” between Beijing, Kabul, and Islamabad. Following a recent terrorist attack against a girls’ school in Kabul, believed to be carried out by the Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP), China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying sought to lay blame on the United States, criticizing Washington’s abrupt withdrawal for contributing to instability. As much as China deplores a U.S. military presence on its border, the same presence has kept a lid on the dangerous militant groups operating in Afghanistan, Pakistan, and other parts of South and Central Asia.

Some counterterrorism analysts have speculated that with the U.S. withdrawing its troops, and with China becoming a more visible presence throughout South Asia, Beijing could find its diplomats and assets targeted by terrorists with increasing frequency. According to a recent report by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, terrorist groups in Pakistan, including the Tehrik-e-Taliban (TTP) and ethnic Baluch separatist groups, have begun cooperating to push back against China’s growing influence. China’s widespread oppression of Uyghur Muslims, which some, including several Western countries, have labeled a genocide, has drawn the ire of jihadist groups such as al-Qaeda. In 2019, al-Qaeda’s general command released a statement expressing solidarity with the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) and the Uyghur people. China is concerned that if Afghanistan descends into chaos, it will provide fertile ground for militants rebuild a safe haven to network and train. Uyghur militants with combat experience in Syria are a particular concern for Beijing.

China increasingly views the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan through the lens of great power competition. For the past two decades, Washington has been bogged down in a resource-draining counterinsurgency operation which has divided the United States politically, an ancillary benefit to Beijing. The U.S.-led Global War on Terror has also provided China with a degree of cover for its own campaign against the Uyghurs. Under the guise of shared counterterrorism interests, Beijing has frequently inflated the threat posed by Uyghur militants and used that as a pretext to carry out its repressive campaign in Xinjiang. For its part, the United States’ decision to withdraw from Afghanistan is also shaped by great power competition. Because Washington views Beijing as its primary adversary, there is a growing chorus in the Beltway (Washington DC) calling for “ending endless wars” and repurposing military assets for competition with near peer rivals, including China and Russia. China also recognizes that as the U.S. draws down its commitment in Afghanistan, Beijing will be compelled to increase its own development aid and diplomatic resources, which will be essential to stability. China is cautious not to become overly involved, however, cognizant to avoid the trap that has befallen so many other great powers that have been drawn into the “Graveyard of Empires.”