Abstract: Over 1,000 adult male foreign fighters, women, and minors from the Western Balkans spent time in Syria and Iraq and around 500 from the region are still there, including children born in theater. After seven years of fighting and at least 260 combat deaths, the last active jihadi unit from the Western Balkans in Syria and Iraq is a modest ethnic Albanian combat unit fighting with Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in Idlib. The rest of those remaining in Syria and Iraq, mostly minors, are held in Kurdish-controlled IDP camps. Some 460 others have gradually returned home, making the Western Balkans the region with the highest concentration of returning foreign terrorist fighters in Europe and creating a long-term security challenge compounded by inadequate resources and the threat posed by homegrown jihadi militants.

The Western Balkans emerged as a meaningful source of European foreign fighters in the Syrian conflict.1 Although it appeared suddenly, this jihadi mobilization wave did not materialize in a vacuum. It was and remains the most visible manifestation of a wider religious militancy phenomenon in the region. This article will examine both parts of the phenomenon: the current state of the Western Balkans foreign fighter contingenta and the complex challenge they represent as well as the scope and significance of the homegrown jihadi pool in the region. The metrics provided in this article have been compiled from data that was last updated in early to mid-2019 and was provided or released by Western Balkans law enforcement agencies and/or collected from a wide range of reports released by international organizations and academic institutions.

Part One: Exploring the Western Balkans Foreign Fighters Contingent

Data and Observed Trends

Since 2012, about 1,070 nationalsb of Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, and Montenegro traveled to Syria and Iraq, primarily joining the ranks of the Islamic State and in lesser numbers the al-Qa`ida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra—most recently rebranded Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). This unprecedented outflow of foreign fighters from the region peaked in 2013-2014 and almost grinded to a halt by 2016,2 although aspiring jihadi militants continued their largely unsuccessful attempts to cross into Syria well into 2017.3 About two-thirds of the contingent, or 67 percent, were male adults at the time of departure, 15 percent women, and 18 percent children.c Kosovo contributed the region’s largest number of men (256),4 whereas Bosnia and Herzegovina contributed the highest number of women (61) and children (81).5

Due to new births between 2012 and 2019, the number of children of foreign fighters from the Western Balkans in Syria and Iraq has sizably increased. According to official data, the number of children born in theater to Kosovan and Bosnian parents as of early 2019 stood at 155.d These new births have further increased the size of the Western Balkans contingent who have spent time in Syria and Iraq to at least 1,225.e

In the last seven years, about 260 of those who traveled to Syria and Iraq from the Western Balkans have been reportedly killed in armed hostilities, or, in a few cases, died of natural causes. That represents almost one-quarter of the original contingent of 1,070 individuals. Some 460 others have returned to their countries of nationality or residence.f The majority had returned by 2015.g A few others were transferred to North Macedonia by the U.S. military in 20186 after being captured by the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), thus making that country one of the first in Europe to publicly repatriate Islamic State fighters detained in Syria.7 The repatriation continued in April 2019 with Kosovo accepting the transfer of 110 individuals, of whom 74 are children, 32 women, and four alleged male foreign fighters. This was one of the largest repatriations of its kind so far.8 Bosnia and Herzegovina repatriated only one alleged foreign fighter.9

The author estimates the size of the Western Balkans contingent of foreign fighters and family members remaining in Syria and Iraq stands at over 500 individuals, made up one-third by male combatants and two-thirds by children (including those born in theater) and women.h They are mostly being held in Kurdish-controlled prisons and camps for displaced people while a smaller number continues to be embedded with the organizations they joined in Syria and Iraq.10 At least two foreign fighters, one from North Macedonia and one from Kosovo, are serving life sentences in Turkey.11 Nationals of Bosnia and Herzegovina currently compose the largest group of the Western Balkans contingent remaining in the conflict theater.i

As of mid-2019, the largely mono-ethnic Islamic State-affiliated units of Western Balkans foreign fighters appear to no longer be active in the conflict theater. This is mostly due to successful targeting of their leadership by U.S.-led coalition airstrikes and considerable battlefield casualties that have caused a significant drop in the presence of active Western Balkans foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq, likely to the lowest point since the beginning of the jihadi outflow in 2012.12

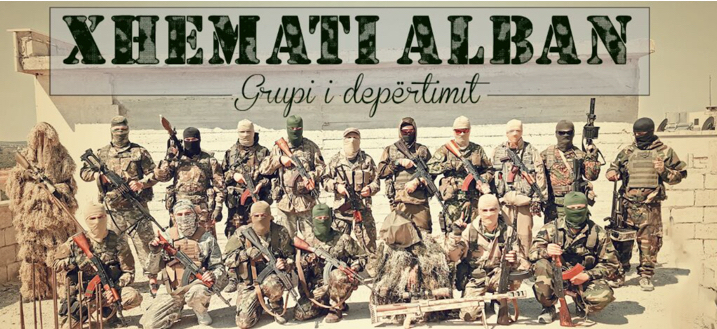

The last active jihadi presence from the region in Syria is an ethnic Albanian unit within HTS. Xhemati Alban is a katiba (combat unit) composed of ethnic Albanian fighters operating in and around the northwestern Syrian province of Idlib. Combatants of other Western Balkans ethnicities continue to fight with HTS, but ethnic Albanians appear to be the only ones from the region to still operate a mono-ethnic unit with its commanding structure.13 This may be indicative of both a sufficiently large number of fighters and adequate military capabilities. Research by the authorj and linguistic idiosyncrasies from propaganda footage indicate that these fighters originate primarily from North Macedonia and Kosovo. Video and photographic propaganda material released between 2017-2018 by an affiliated media outlet suggest the unit may have up to two dozen active fighters in its ranks.k Other martyrdom propaganda footage indicates that the unit may have suffered at least 18 combat deaths, one after a SVBIED attack during an offensive in Aleppo in late February 2016.14 The latest martyrdom announcement was issued by the unit’s official propaganda channel on May 13, 2019.

The unit’s commander is Abdul Jashari, a 42-year-old ethnic Albanian citizen of North Macedonia, going by the nom de guerre Abu Qatada al-Albani. Jashari is an influential figure and close military advisor to Abu Muhammad al-Julani, the leader of HTS, who appointed Abu Qatada al-Albani in the summer of 2014 to lead the organization’s military operations in Syria.15 The U.S. Treasury Department designated Jashari a terrorist on November 10, 2016.16 His name appeared recently in HTS communiqués as one of the members of a high committee tasked with leading reconciliation efforts with Hurras al-Din, a jihadi faction affiliated with al-Qa`ida.17

As part of Xhemati Alban’s continued engagement and propaganda efforts via social media channels targeting audiences in the Balkans, in August 2018, the group released a 33-minute video entitled “Albanian Snipers in the Lands of Sham.”18 This high-quality propaganda video, narrated in Albanian with English subtitles, documents various stages of training, planning, and combat efforts of the unit’s sniper squad, which appears to be self-sufficient both at weapons craftsmanship and tactical training. Its members use customized, high-precision rifles with relatively expensive scopes and craft-made suppressors.19 The skillsets displayed in the video indicate possible ex-military or paramilitary background and affiliation.

The Complex Challenge of Returnees

From the start of the Syrian armed conflict, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and North Macedonia experienced some of the highest rates in Europe for mobilization into jihadi terrorist organizations relative to population size.20 A similar trend has characterized the reverse flow, where according to official data about 460 individuals from the region have returned home from Syria and Iraq, 242 of whom to Kosovo.21 By comparison, the countries of the European Union, with a cumulative population size of 500 million, have received about 1,500 returnees.22 As data indicates, the Western Balkans is currently the region with the highest concentration of returned foreign fighters in Europe. With some 500 other adult male combatants, women, and minors still in Syria, it is not inconceivable that the number of returnees may double in size in the future. Kosovo, with its 134 returnees per million nationals, tops the chart, followed by North Macedonia with 42 per million. The United Kingdom, by comparison, has reported about 6 returnees of “national security concern” per million, whereas Germany and France about four per million.l The scale of the Western Balkans challenge in dealing with the long-term social and national security implications of this considerable wave of returnees becomes clearer when considering the very modest resources and capacities available in the region compared to the rest of Europe.

The emerging practice of stripping citizenship or permanent residence to foreign fighters that is gaining traction in some European countries might complicate things further for the Western Balkans, as it shifts the burden of prosecuting and handling dozens of returnees with dual nationality to countries already overburdened and ill-equipped to do so both in terms of resources and expertise.m In October 2018, Kosovan authorities accepted the transfer from Turkey of an ethnic Albanian Islamic State fighter and his three children. He was born in Germany to parents that had emigrated there from Kosovo.23 That was after Germany revoked his permanent residence permit although he had lived all his life in Germany, had reportedly been radicalized there, and fought in Syria with the so-called “Lohberger Brigade,” a German-speaking jihadi unit.24 He was swiftly indicted, tried, and found guilty in Kosovo within a three-month timeframe for “organizing and participating in a terrorist group.”25 Though, after pleading guilty, he received a five-year prison sentence, that was only for the crime of joining a terrorist organization rather than possible crimes committed during the four years spent fighting with the Islamic State in Syria.n

Despite significant capacity and resource challenges, the Western Balkans countries have tried and sentenced a significant number of returning jihadis. Kosovo has been at the forefront of these efforts with 73 successful prosecutions of male returnees as of early 2019, which is more than all the other countries of the region combined.26 That is six out of every 10 returnees. By comparison, the United Kingdom has prosecuted one in 10 jihadis returning from Syria, for a total of about 40 individuals.27 o Courts in North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina—the other two countries with the largest numbers of returnees in the Western Balkans—have issued guilty verdicts against 32 and 18 of their foreign fighter nationals, respectively.28

Yet, due to generally lenient sentencing regimes29 in the countries of the Western Balkans, often based on plea bargains, the prison sentences in terrorism-related cases have largely ranged from one to six years with few exceptions in cases of prominent recruiters.30 For example, in Kosovo, the average sentence in terrorism-related cases has been 3.5 years.31 As a result, about 40 percent of those sentenced for terrorist offenses in Kosovo in the past few years have already been released from prison.p In Bosnia and Herzegovina, sentencing leniency has gone even further. In one criminal proceeding, a defendant holding dual Bosnian and Austrian citizenship entered a guilty plea for providing recurrent financial support to the Islamic State and settled with the court to pay a fine of about $15,000 in lieu of a one-year prison sentence.32 Another returning foreign fighter was sentenced in late 2016 to one year in prison after admitting that going to Syria was a mistake.33 On average, the 25 individuals prosecuted and sentenced by a court of appeals verdict in Bosnia and Herzegovina have received prison sentences of one year and 11 months for terrorism-related activities, including fighting in Syria.34

Overall, the sentences handed down in the Western Balkans for terrorism offenses are among the most lenient in Europe. The average sentence in the European Union for terrorism-related offenses was five years in 2017.35 The average increased to seven years in 2018.36 By comparison, the average sentence for criminal offenses related to the Islamic State in the United States in mid-2019 stood at 13.5 years in prison.37 Yet, while E.U. countries have the resources, capabilities, and practical experience required to develop and implement prison-based rehabilitation and post-incarceration aftercare programs—including employment assistance and socioeconomic incentives—that is not the case in the Western Balkans. Uneven progress has been made to date toward putting in place any meaningful rehabilitation and reintegration programs for returning foreign fighters, women, or minors.38 Although detailed strategies and action plans have been drafted across the region, inadequate allocation of funding has hampered their implementation and impact.39

Another concern related to foreign fighter returnees is the likelihood that some may have returned to the region with the assistance of support networks without being detected by the authorities, or at least have been able to evade them for some time. An alleged Kosovo-born Islamic State recruiter and a U.S. permanent resident at the time of travel to Syria in 2013, relocated to Bosnia and Herzegovina in January 2017 using fake travel documents. He was able to hide in Sarajevo for about six months using numerous fake identities before being arrested, at which time he was reportedly found in possession of passports from six countries.40 He was extradited to the United States in October 2017 where he has been indicted. While the purpose of his relocation to Bosnia and Herzegovina remains unclear, he could face a life sentence in the United States if found guilty.41

In another case, a former Islamic State foreign fighter of Kosovan citizenship was arrested in February 2019 by the Albanian customs authorities while attempting to board a ferry to Italy using a forged North Macedonian passport. In January 2017, a court in Kosovo had sentenced him to two years and six months in prison, but the police had been unable to locate him following the completion of the trial until he resurfaced in Albania.42 Both of these cases illustrate the ability of these returning foreign fighters to evade law enforcement authorities, travel and relocate abroad, and obtain travel documents under false identities. In other cases, returnees under house arrest absconded and returned to Syria.43 All the above is unlikely to have happened without the logistic and financial assistance of support networks with criminal connections.

Part Two: Examining the Scope and Significance of the Homegrown Jihadi Pool

The unprecedented jihadi mobilization wave of the last decade in the Western Balkans may have been sudden in its manifestation, but it did not occur in a vacuum.44 As such, the foreign fighters are only the most visible manifestation of a wider phenomenon of religious militancy in the Western Balkans, the size and threat of which is not easily measured. Numerous counterterrorism operations resulting in hundreds of arrests, convictions, and various foiled terrorist attacks have revealed the instrumental role of well-integrated radicalization, recruitment, and mobilization networks organized around salafi enclaves, ‘unofficial’ mosques, and a variety of faith-based charities, movements, and associations run by local fundamentalist clerics and religious zealots.45

In essence, observed radicalization and mobilization patterns are similar to those elsewhere in Europe, where known salafi organizations like Sharia4Belgium, Millatu Ibrahim, and Die Wahre Religion have been heavily linked to foreign fighter flows to Syria and Iraq. In 2015, for example, a court in Belgium found 45 members of the salafi organization Sharia4Belgium guilty of sending fighters to Syria and other terrorist-related offenses.46 In 2016, Germany banned Die Wahre Religion (The True Religion) known for its proselytizing campaign “Lies!” (Read!) that was also active in the Balkans—about 140 of the group’s supporters are known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq.47 One key difference, nonetheless, is that in the Western Balkans, the proliferation of ultraconservative organizations with political agendas was enabled by the post-Balkans conflict environment, where these entities were able to exploit societal vulnerabilities and rifts, mixing humanitarian aid with salafi indoctrination and militantism.48

While the contingent of Western Balkans foreign fighters is only the most visible manifestation of the terrorist threat in the region, questions abound as to the size of the less visible component of the problem: the contingent of radicalized individuals that has often provided ideological, logistical, or financial support to foreign fighters and at times has been responsible for plotting terrorist attacks. In a way, terrorism-related arrests and failed plots make some aspects of this problem set more visible. Although no official data exists for these countries, data and trends observed elsewhere in European countries may provide a general indication of the possible size of the problem in the Western Balkans.

According to a report on the terrorist threat in France presented to the French Senate, as of March 2018 the French intelligence services had identified 1,309 French nationals or residents who had traveled to Syria and Iraq since 2012.49 The same report indicated that as of February 2018, the “Fichier de traitement des Signalements pour la Prévention de la Radicalisation à caractère Terroriste,” (FSPRT) a database used by French security services to monitor and assess the magnitude of the domestic terrorist threat posed by Islamist extremists,q had 19,725 “active profiles/entries” of radicalized individuals, 4,000 of which considered “particularly dangerous.”50 r In France therefore, the number of radicalized individuals considered to pose a potential national security threat is about 15 times higher than the number of known foreign fighters.

Similarly, the British MI5 has over the years identified 23,00051 onetime jihadi extremists living in the United Kingdom, 3,000 of whom were the focus of 500 ongoing terrorism investigations or monitoring operations in early 2017.s By comparison, the number of reported British foreign fighters in July 2017 stood at about 850,52 making the number of the homegrown jihadi—posing either a residual or active national security threat—about 27 times higher than the number of foreign fighters.

It is very possible the divergence between the French and United Kingdom ratios is because the FSPRT list and the MI5 list are based on different criteria. But based on the similar trends observed in France and the United Kingdom regarding the much larger size of the homegrown jihadi population relative to the foreign fighter contingent, it would not be inconceivable to assume at least a 15:1 homegrown jihadi to foreign fighter ratio in the Western Balkans context.t Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that methodologies for measuring terrorist radicalization and national security threat differ from country to country. Also, while similar in some ways, jihadi radicalization trends are not uniform across countries as they result from the interplay of a variety of socio-political, historical, and ideological variables that are largely country and region specific.

Two other indicators point to the existence of a robust and ideologically committed contingent of jihadi militants operating in the Western Balkans: the persistent activities of ‘social media jihadis’ who openly support and disseminate the ideology and propaganda of terrorist organizations, and the unprecedented number (as far as the region is concerned) of both foiled terrorist attacks and arrested homegrown terrorists in recent years. Following the clampdown on accounts disseminating jihadi content by Facebook, local ‘social media jihadis’ have partially migrated over the past years to other social media platforms such as the messaging application Telegram, which has a relatively less aggressive content removal policy.u

Research conducted for this assessment on the week of March 11, 2019, identified 27 active (not requiring membership) Telegram channels/pages in the Albanian language and 6,352 subscribers/accounts that followed one or more of these pages operated by militants and/or fighters of the Islamic State (13 channels), HTS (six channels), or generic jihadi supporters (eight channels).v The content circulated through these channels focused on promotion of jihad; sharing news bulletins from official media channels of jihadi organizations operating in various conflict theaters; salafi literature; sermons of local and foreign salafi clerics generally imprisoned for terrorism-related activities; propaganda videos and infographics; and jihadi nasheeds.w

While in the past couple of years there has been a drop in jihadi media output in Western Balkans’ languages,x an avid cadre of committed ‘social media jihadis’ continue to engage regularly with audiences online, disseminate jihadi propaganda, recruit, incite violence, and even plot attacks. In late 2017, a court in Kosovo sentenced an Islamic State supporter to one year and six months in prison for using social media platforms to incite attacks against Kosovan government institutions and foreign embassies.53 A few months later, another Islamic State supporter, the sibling of a Kosovan Islamic State suicide bomber, received a sentence of 200 hours of community service for inciting vehicular attacks via social media.54 In October 2018, they were both found guilty on additional charges, the first for attempting to enlist support and funding for a suicide attack and the other for not reporting the case to the police.55

Terrorist plots have been successfully disrupted by counterterrorism operations in the past three years in Kosovo, Albania, North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Serbia. In a 2016 foiled plot involving an advanced Islamic State-directed plan to carry out simultaneous attacks in the region, including one on the Israeli national soccer team visiting Albania, nine Kosovan citizens were found guilty.56 According to the prosecution, one of the perpetrators had previously fought in Syria and some of the plotters were taking directives on the attack from their compatriots in leadership positions within the Islamic State.57

In 2015, two soldiers were killed in the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina by an armed Islamist gunman who blew himself up after carrying out the attack. Notes glorifying the Islamic State were found in his house.58 In June 2018, Kosovan authorities reportedly foiled another attack targeting NATO forces stationed in Kosovo.59 One of the plotters was arrested previously for attempting to travel to Syria and another one was expelled from Italy.60 The latest foiled attack was reported in North Macedonia on February 15, 2019, where the police arrested 20 alleged Islamic State supporters.61

In sum, some returnees from Syria and Iraq have reportedly been involved in terrorism-related activities and found in possession of illegal firearms and explosives upon their return.62 Yet, the foiled terrorist plots have largely involved individuals not known to have traveled to Syria and Iraq, although in many cases they were related to or associated with known foreign fighters. Judging from this perspective, the homegrown jihadis have so far been a more significant source of domestic security threat than foreign fighters.

Conclusions

This assessment has found that the presence of Western Balkans foreign fighters currently active in Syria and Iraq is likely at the lowest point since 2012 and the remaining contingent of about 500 individuals is made up for two-thirds by minors and women. While already the region with the highest concentration of returning foreign fighters in Europe, additional repatriations are bound to compound the Western Balkans’ long-term social and security challenge further.

In light of the sizable wave of returnees from Syria and Iraq, special attention and resources should be dedicated to assessing, monitoring, and actively countering the robust jihadi networks in the region. The considerable numbers of terrorism-related arrests, convictions, and foiled attacks in the Western Balkans clearly indicate that the countries of the region have stepped up their CT efforts in response to a heightened terrorist threat. Yet, unless adequately augmented, scarce resources and capacities will likely continue to hamper the scope and effectiveness of these efforts. Prison sentences that are not matched by substantive prison-based rehabilitation and post-incarceration supervision and support efforts are unlikely to duly mitigate the social and security risks posed by returnees and homegrown terrorist offenders.

Policy makers should consider proactively adjusting national security responses to the demographic shifts observed in the composition of the remaining Western Balkans contingent in Syria, currently dominated by noncombatants. The “children of the Caliphate,” including those from the Western Balkans, will likely represent a long-term challenge with national security implications. As such, there is a strong case for prioritizing efforts addressing this complex challenge.

Substantive Notes

[a] In this article, “Western Balkans foreign fighter contingent” encompasses—without prejudice to participation in armed combat or implication (direct or indirect) in terrorist activity—all nationals of Western Balkans countries reported by law enforcement authorities to have spent time in areas controlled by designated terrorist organizations in Syria and Iraq from 2012. It is important to emphasize that minors are a distinct, largely noncombatant subgroup considered part of this contingent due to national affiliation and association with their adult parents. Nevertheless, it is also important to note that many children and minors of all nationalities who have transitioned into adulthood while in Syria and Iraq have systematically received ideological and military training in camps for “the cubs of the Caliphate” and, in some cases, have directly participated in armed combat, execution of prisoners, and suicide attacks. See John Horgan, Max Taylor, Mia Bloom, and Charlie Winter, “From Cubs to Lions: A Six Stage Model of Child Socialization into the Islamic State,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, September 10, 2016. See also Asaad Almohammad, “ISIS Child Soldiers in Syria: The Structural and Predatory Recruitment, Enlistment, Pre-Training Indoctrination, Training, and Deployment,” ICCT, February 2018.

[b] Total number compiled based on data from each of the six Western Balkans countries. For Albania, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Albania 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 36; for Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Kosovo* 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 32; for North Macedonia, see “Commission Staff Working Document, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 38; for Bosnia and Herzegovina, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018 Report, European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 25; for Montenegro, see “2019 Transitional Action Plan for the Continued Implementation of Activities in the Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism 2016-2018,” Government of Montenegro, January 2019, p. 38; for Serbia, see Joana Cook and Gina Vale, “From Daesh to ‘Diaspora’: Tracing the Women and Minors of Islamic State,” ICSR, 2018, p. 16.

[c] The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child defines child as “a human being below the age of 18 years.”

[d] According to interviews with representatives of law enforcement agencies and investigative journalists from the two countries, as of early 2019, the number of children born to Kosovan nationals was 78 and that of children born to Bosnian nationals was 77. Author interviews, early 2019. For Bosnia and Herzegovina, see also Admir Muslimovic, “Authorities Negotiating the Return of Fighters, Women and Children from Syria,” Detektor, February 2, 2019.

[e] The reason it was at least this number (and likely higher) is because at the time of this publication, there was no official data available for newborn children of citizens of Albania, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia in Syria and Iraq.

[f] These numbers are derived by the author from various sources. For Albania, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Albania 2018 Report,” p. 36; for Montenegro, see “2019 Transitional Action Plan for the Continued Implementation of Activities in the Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism 2016-2018,” p. 38; for North Macedonia, see “Commission Staff Working Document, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report,” p. 38, and also Ryan Browne, “US transferring some ISIS detainees from Syria to their home countries,” CNN, August 7, 2018; for Bosnia and Herzegovina, see Daria Sito-Sucic, “Bosnian women struggle to return female relatives, children from Syria,” Reuters, March 8, 2019; and for Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Kosovo* 2018 Report,” p. 32, and Taulant Qenaj, “The Hard Reintegration of Returnees from Syria,” Radio Free Europe, May 7, 2019. Updated information was also received directly from Western Balkans law enforcement representatives in early 2019.

[g] About 300 foreign fighters and family members had returned to the Western Balkans by the end of 2015. This figure is derived by the author from a number of sources. For Bosnia and Herzegovina, see “Bosnia To Shut Down Radical Muslim Groups After Imam Threatened,” Radio Free Europe, February 27, 2016; for North Macedonia, see Lirim Shabani, “Spasovski: The Returnees Are Being Monitored,” Telegrafi, March 25, 2016; for Albania, see Aleksandra Bogdani, “Albania faces ‘Jihadi Fighters in the Shadows’ Threat,” BalkanInsight, March 23, 2016; and for Kosovo, see Adrian Shtuni, “Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo,” United States Institute of Peace Special Report 397 (2016).

[h] This number is derived by the author from various sources with the assumption that individuals not reported as dead or returned are still in Syria and Iraq. It is likely that some foreign fighters relocated to other countries or have slipped back home without being detected by local authorities. For Albania, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Albania 2018 Report,” p. 36; for Montenegro, see “2019 Transitional Action Plan for the Continued Implementation of Activities in the Strategy for Countering Violent Extremism 2016-2018,” p. 38; for Bosnia and Herzegovina, see Sito-Sucic; for Serbia, see Maja ivanovic, “After ISIS Collapse, Serbian Women Trapped in Syria,” BalkanInsight, April 25, 2019; and for Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document Kosovo* 2019 Report,” European Commission, May 29, 2019, p. 38.

[i] Starting from 2012, Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina with 358 and 323 nationals, respectively, were the two main contributors of Western Balkans foreign fighters to Syria and Iraq. As of mid-2019, Kosovo has experienced 242 returns (including 110 in April 2019). By comparison, Bosnia and Herzegovina has experienced only about 60 returns, of which single digit were children. Given the much smaller number of Bosnian returnees and information provided by Bosnia’s prime minister in mid-March that 102 Bosnian adults remained in theater, it follows that Bosnian nationals currently compose the bulk of the Western Balkans contingent remaining in Syria and Iraq. For Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document Kosovo* 2019 Report,” p. 38; for Bosnia and Herzegovina, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018 Report,” p. 25, and also Cook and Vale, p. 16, and Amina Bijelonja, “The Returnee From Syria Cufurovic Was Transferred to Zenica Prison,” Voice of America, April 22, 2019.

[j] The author monitored their social media channels and discussed the subject with law enforcement contacts from the Western Balkans.

[k] This propaganda was tracked by the author between 2017-2018 on a Telegram messaging channel affiliated with Xhemati Alban.

[l] These numbers are calculated by the author from the tabulation of foreign fighters per country in Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign fighters and the threat of returnees,” Soufan Center, October 2017 as well as other sources reporting on the most recent transfer of foreign fighters in the Western Balkans. For North Macedonia, see “Commission Staff Working Document, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report,” p. 38, and also Browne; for Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Kosovo* 2018 Report,” p. 32, and Qenaj.

[m] Determining the size of the pool of Western Balkans foreign fighters and homegrown jihadis with dual nationality or residence in Western countries is beyond the scope of this article. Yet, information provided in various publications appears to indicate that the size is not insignificant. According to the U.S. State Department’s “Country Reports on Terrorism 2016,” of the 300 Austrian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq and those prevented from departing, ethnic Bosnians represent the second-largest group after the Chechens who had entered Austria as asylum seekers over the past decades. Furthermore, a recent study by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences on 130 Swiss-based jihadis—including 72 foreign fighters—monitored by the Swiss intelligence service FIS revealed that about one-third of them have a Western Balkans background. For more, see Miryam Eser Davolio, Mallory Schneuwly Purdie, Fabien Merz, Johannes Saal, and Ayesha Rether, “Updated review and developments in jihadist radicalization in Switzerland – updated version of an exploratory study on prevention and intervention,” June 2019.

[n] Recent research has emphasized the legislative and practical challenges of collecting admissible forensic evidence for the successful prosecution of crimes that may have been committed in foreign war zones by returning foreign fighters. For more on this, see Christophe Paulussen and Kate Pitcher, “Prosecuting (Potential) Foreign Fighters: Legislative and Practical Challenges,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism – The Hague, January 30, 2018.

[o] There are many possible reasons determining the number of successful prosecutions in each country, including the different standards and rules of admissible evidence in court that vary across legal systems and the different use of negotiated agreements such as plea bargains.

[p] According to information issued by Kosovo judicial authorities and obtained by the author as of March 2019, Kosovan authorities have successfully prosecuted and sentenced 73 returning foreign fighters and 33 individuals found guilty for recruiting, providing support, and engaging in terrorist activities domestically. Of the 106 convicted individuals, 42 had been released after serving their sentence.

[q] Editor’s note: FSPRT contains only radical Islamists, while the Fiches S (another list maintained by French authorities) includes other types of threats to the national security. FSPRT is specific to Islamist radicalization. Jean-Charles Brisard communication to this publication, July 2019.

[r] These 4,000 individuals categorized as “particularly dangerous” met at least one of the following criteria: demonstrated a strong desire (verified instead of assumed) to travel abroad to wage jihad; had a proven link to a terrorist activity or network; and/or were reported as a dangerous Islamist radical.

[s] This contingent of 23,000 individuals is considered by the authorities to pose different levels of security risk. Following the May 22, 2017, Manchester Arena bombing the United Kingdom’s Security Minister Ben Wallace announced that 3,000 “subjects of interest” were the focus of 500 active terrorism investigations whereas 20,000 “former subjects of interest” who were previously investigated were considered to constitute a residual risk. It is likely that some of the previously investigated individuals no longer pose a threat. Yet, the Manchester Arena bomber, Salman Abedi, was a “former subject of interest,” which exemplifies the challenge of accurately assessing the level of threat posed by each subject of interest. For more on this, see Raffaello Pantucci, “Britain on Alert: The Attacks in London and Manchester and the Evolving Threat,” CTC Sentinel 10:7 (2017).

[t] The 15:1 projection is based on the smaller homegrown jihadi to foreign fighter ratio per available information in the cased of France; the projection would be higher if the ratio of the United Kingdom is applied. It should be pointed out that due to the very dynamic nature of terrorist radicalization, the databases of radicalized individuals considered to pose a potential terrorist threat may contain false positives but also miss cases of terrorist radicalization. In the case of France, according to a recent study by GLOBSEC, about 80 percent of the individuals behind 22 terrorist incidents were on terrorist watchlists. The rest were not previously known to the authorities. See Ken Dilanian, “Report: Nearly all terror attacks in France carried out by suspects already known to police,” NBC, January 6, 2019. A more precise assessment of the actual size of the pool of radicalized individuals posing a potential national security threat in the Western Balkans would require more specific research.

[u] This migration of Western Balkans ‘social media jihadis’ to Telegram followed a broader trend shift of the Islamic State and other terrorist groups’ communication strategy worldwide. For more on this, see Bennett Clifford and Helen Powell, “Encrypted Extremism, Inside the English-Speaking Islamic State Ecosystem on Telegram,” George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, 2019.

[v] The total number of subscribers to the 27 channels may not necessarily represent unique individuals/followers.

[w] Despite efforts by Telegram to suspend these channels, they are quickly reactivated by their administrators under slightly different names. Hundreds of subscribers would follow the reactivated channels within a short time. During the timeframe of monitoring, despite fluctuations, the number of channels and subscribers remained roughly the same. In the same timeframe, the active Facebook account of an ethnic Albanian foreign fighter posting from Syria had 1,150 followers, while the account of another ethnic Albanian returned and incarcerated Islamic State foreign fighter had over 2,700 followers.

[x] This trend observed by the author may have resulted from a number of reasons, including the aggressive policies adopted by social media platforms and the decimated capacities of Islamic State media outlets.

Citations

[1] A.J. Naddaff, “Kosovo, home to many ISIS recruits, is struggling to stamp out its homegrown terrorist problem,” Washington Post, August 24, 2018; “Bosnia: Islamic state group prime recruitment hotbed in Europe,” France 24, December 21, 2015; Carlotta Gall, “How Kosovo was turned into fertile ground for ISIS,” New York Times, May 21, 2016.

[2] For Albania, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Albania 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 36; for Kosovo, see “Commission Staff Working Document, Kosovo* 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 32; for North Macedonia, see “Commission Staff Working Document, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 38; for Bosnia and Herzegovina, see “The Western Balkans: Transition Challenges, European Aspirations and Links to the MENA Region,” NATO Parliamentary Assembly, April 21, 2017, p. 8.

[3] “Commission Staff Working Document, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia 2018 Report,” p. 38.

[4] Updated official data provided by Kosovo Police to the author in early 2019. See also “Commission Staff Working Document, Kosovo* 2019 Report,” p. 38.

[5] “Commission Staff Working Document, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2018 Report,” European Commission, April 17, 2018, p. 25.

[6] Ryan Browne, “US transferring some ISIS detainees from Syria to their home countries,” CNN, August 7, 2018.

[7] Carlo Munoz, “Pentagon praises Macedonia for repatriation of ISIS foreign fighters,” Washington Times, August 7, 2018; Browne.

[8] “110 Returnees from Syria to Kosovo,” Voice of America, April 20, 2019.

[9] “Bosnia brings back, detains Islamic fighter from Syria,” Reuters, April 20, 2019.

[10] “Syria war: Kosovo brings back 110 citizens including jihadists,” BBC, April 20, 2019.

[11] “Men behind first DAESH attack in Turkey get multiple life sentences,” Daily Sabah, June 15, 2016.

[12] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2017,” U.S. Department of State, September 19, 2018, p. 98. See also “SIPA: Bajro Ikanovic, a Bosnian citizen previously convicted on terrorism charges, killed in Iraq,” Klix, March 23, 2016; “Al-Kosovi, Commander of Albanian ISIS jihadis, killed in Syria,” Balkanweb, February 8, 2017; and “Albanian ISIS commander reported dead,” Kallxo, April 4, 2016.

[13] These observations are based on the author’s monitoring of jihadi activities of Western Balkans individuals in Syria and Iraq and communications with law enforcement authorities from the Western Balkans.

[14] Adrian Shtuni, “OSINT Summary: Video eulogizes Albanian Jabhat al-Nusra suicide bomber in Syria’s Aleppo,” IHS Jane’s, July 8, 2016.

[15] Thomas Joscelyn, “Leaked audio features Al Nusrah Front emir discussing creation of an Islamic emirate,” FDD’s Long War Journal, July 12, 2014.

[16] “Counter Terrorism Designations and Updates,” U.S. Department of the Treasury, November 10, 2016.

[17] Thomas Joscelyn, “Analysis: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Hurras al-Din reach a new accord,” FDD’s Long War Journal, February 15, 2019.

[18] Aaron Zelin, “New video message from Hayy’at Tahrir al-Sham: Albanian Snipers in al-Sham,” jihadology.net, August 4, 2018.

[19] “The Albanian Sniper Squad in Syria and their Weapons,” Calibre Obscura, December 12, 2018.

[20] Adrian Shtuni, “Dynamics of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo,” United States Institute of Peace Special Report 397 (2016).

[21] “Commission Staff Working Document Kosovo* 2019 Report,” European Commission, May 29, 2019.

[22] Eric Schmitt, “Defeated in Syria, ISIS fighters held in camps still pose a threat,” New York Times, January 24, 2018.

[23] “Kosovo detains man suspected of joining Syria terror groups,” Associated Press, October 9, 2018; Bjorn Stritzel, “9. Dernjani is now scheduled to be deported to Kosovo,” Twitter, June 10, 2018; “Germany requested Kosovo to handle the case of the ISIS Albanian fighter who raped minors,” Insajderi, December 2018.

[24] “ISIS fighter from Dinslaken sentenced to five years in prison,” Bild, January 15, 2019.

[25] Mirvet Thaqi, “The accused who pled guilty to participating in a terrorist group received a five year prison sentence,” Betimi Per Drejtesi, January 14, 2019.

[26] This is according to information issued by judicial authorities in the Western Balkans and obtained by the author.

[27] Lizzie Dearden, “Only one in 10 jihadis returning from Syria prosecuted, figures reveal,” Independent, February 21, 2019.

[28] This is according to information received by judicial authorities in the Western Balkans.

[29] “Country Reports on Terrorism 2017,” U.S. Department of State, September 19, 2018, p. 76.

[30] Sabina Pergega, “Spectacles, trials and sentences handed down to individuals accused of participating and inciting participation in the ‘war of nobody,’” Betimi Per Drejtesi, January 2, 2018; Zijadin Gashi, “Zeqirja Qazimi and six others sentenced to 42 years in prison for terrorism,” Radio Free Europe, May 20, 2016.

[31] This is according to information issued by Kosovo judicial authorities and obtained by the author.

[32] Haris Rovcanin, “Bosnian ISIS backer avoids jail by paying fine,” Balkan Insight, December 19, 2016.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Albina Sorguc, “Bosnia Court Jails Syria Fighter for Three Years,” BalkanInsight, April 17, 2019.

[35] “European Union terrorism situation and trend report 2018,” Europol, 2018, p. 20.

[36] “European Union terrorism situation and trend report 2019,” Europol, 2019, p. 26.

[37] “GW tracker: the Islamic State in America,” George Washington University’s Program on Extremism, 2019.

[38] Denis Dzidic, “No deradicalization schemes for Bosnian terror convicts,” Detektor, March 28, 2017.

[39] Albina Sorguc, “Bosnia has plan, but no money, to fight radicalization,” Detektor, December 28, 2018.

[40] “Mirsad Kandic: ISIS’ border guard and intelligence officer,” Radio Free Europe, November 16, 2017.

[41] Brendan Pierson, “Former Brooklyn resident charged in U.S. with aiding Islamic State,” Reuters, November 1, 2017.

[42] “ISIS fighter had evaded law enforcement in Kacanik, arrested in Vlore,” Insajderi, March 13, 2019.

[43] Ervin Qafmolla, “Escape of those accused of terrorism highlights the failure of the justice system in Kosovo,” Gazeta JNK, November 8, 2016.

[44] Adrian Shtuni, “Ethnic Albanian foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq,” CTC Sentinel 8:4 (2015). See also “Bosnia’s Dangerous Tango: Islam and Nationalism,” International Crisis Group, February 26, 2013; Miranda Vickers, “Islam in Albania,” Defence Academy of the United Kingdom, March 2008; Nidzara Ahmetasevic, “Emissaries of Militant Islam Make Headway in Bosnia,” BalkanInsight, December 10, 2007.

[45] “126 years in prison for nine jihadists charged with terrorism,” Top Channel, May 3, 2016; Rory Mulholland, “Muslim radicals in mountain villages spark fears in Bosnia,” Telegraph, April 30, 2016.

[46] “Sharia4Belgium trial: Belgian court jails members,” BBC, February 11, 2015.

[47] Melissa Eddy, “Germany bans ‘True Religion’ Muslim group and raids mosques,” New York Times, November 15, 2016.

[48] Shtuni, “Dynamics of radicalization and violent extremism in Kosovo;” Vickers; “Bosnia’s Dangerous Tango;” Ahmetasevic.

[49] “Terrorist Threat: For a Just but Firmer Republic,” Report 639 (2017-2018), French Senate, July 4, 2018, p. 28.

[50] Ibid., p. 56; Juliette Campion, “Comment les personnes radicalisées sont-elles suivies en France?” (How have radicalized individuals been tracked in France), France Info, March 26, 2018.

[51] Sean O’Neill, Fiona Hamilton, Fariha Karim, and Gabriella Swerling, “Huge scale of terror threat revealed: UK home to 23,000 jihadists,” Times, May 27, 2017.

[52] Grahame Allen and Noel Dempsey, “Terrorism in Great Britain: the statistics,” House of Commons Library, June 7, 2018, p. 28.

[53] Labinot Leposhtica, “Court of appeals increases sentence for Rakip Avdyli,” kallxo.com, 2017.

[54] Arita Gerxhaliu, “Court sentences ISIS Facebook propagator,” kallxo.com, January 31, 2018.

[55] Kastriot Berisha, “Accused terrorists express their ‘regret’ before being sentences by court,” kallxo.com, October 5, 2018.

[56] Sylejman Kllokoqi, “8 Kosovo Albanians jailed on foiled attack on Israeli team,” Associated Press, May 18, 2018.

[57] Leotrim Gashi, “Two verdicts expected on cases related to fourteen indicted of terrorism,” Betimi per Drejtesi, May 18, 2018.

[58] Zdravko Ljubas, “Murder of two Bosnian soldiers an act of terrorism,” Deutsche Welle, November 19, 2015.

[59] “6 charged in Kosovo with planning terror attacks,” Associated Press, October 5, 2018.

[60] “Is ISIS inside Kosovo? Who are the four individuals arrested today for planning terrorist attacks,” Gazeta Express, June 29, 2018.

[61] “Twenty people related to ISIS arrested in North Macedonia,” Koha.net, February 16, 2019.

[62] “Former jihadist wounded in Syria arrested in Pogradec,” Kallxo.com, November 13, 2016.