A cursory glance at recent headlines from Zimbabwe could give one the impression that things are looking up. A recent World Bank report predicted growth of nearly 4 percent this year. The government took a small first step toward compensating farmers whose land was violently seized by the state decades ago. But closer inspection reveals a country with tremendous structural challenges and a government focused only on regime survival.

It is true that good rains have been a boost to the agricultural sector and have eased the burden of hunger in Zimbabwe. But that sector, like all others, is stymied by the ruinous governance that, coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, has left half of the population living on less than a dollar a day. Moreover, citizens cannot count on the favorable rains persisting. Zimbabwe is one of the countries most affected [PDF] by climate change in the world. If it had a government with credibility, Zimbabwe could be an important voice on the international stage advocating for more meaningful action to support adaptation and mitigation measures. But no one is looking to Harare for leadership because its government is synonymous with corruption and repression.

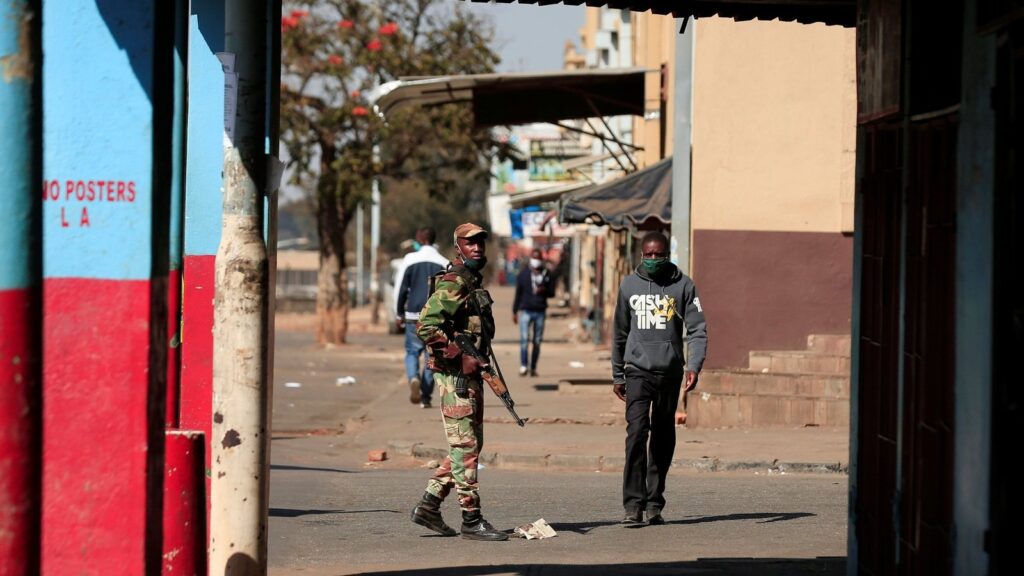

The murky nature of the vehicle the state used for its first payment to former landholders, Kuvimba Mining House Ltd., points to continued patterns of elite enrichment and the absence of accountability at the top. At the same time, the government is engaged in new land seizures, aimed at perceived enemies like civil society leaders, part of its continued campaign to silence dissent and close political space. The state subjects independent journalists to regular harassment and arrest, bullies the judiciary when it shows pockets of independence, and instigates and exploits divisions in the political opposition to silence critical voices in parliament.

Like many other countries in the region, Zimbabwe has an overwhelmingly young population. Any government would find it challenging to steward truly inclusive growth, ensure opportunities for its young people, address the realities of climate change, and strengthen governing institutions and public trust. But the record of the current leadership provides little reassurance that it aims for any of these goals. Two-thirds of Zimbabweans believe their country is going in the wrong direction. Without a fundamental change in the nature of governance, they are almost certain to be proved right.