On Sept. 9, Turkey’s Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu embarked on a three-day trip to West Africa, which included stops in Mali, Senegal, and Guinea-Bissau. During his trip, Cavusoglu emphasized Turkey’s support for Mali’s post-coup transition process, struck infrastructure-related commercial deals with Guinea-Bissau, and underscored its commitment to engaging with multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations (UN) and African Union (AU), on addressing security challenges in the Sahel.

Although Turkey’s involvement in West Africa is lower profile than its military intervention in Libya and large-scale investments in Somalia, Ankara has paid considerable attention to the region since Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan visited Mauritania, Mali, and Senegal in March 2018. Turkey has leveraged cautious participation in the Sahel’s counterterrorism initiatives and humanitarian aid supplies, in order to gain the cooperation of West African countries in Erdogan’s global crackdown against the Gulenist Movement — referred to by the Turkish government as the Fethullah Terrorist Organization (FETO) and blamed for the failed 2016 coup attempt — and weaken the standing of Ankara’s geostrategic rivals, France and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Security and humanitarian outreach

Since the 2012 coup in Mali, which exacerbated instability in the Sahel, Turkey has criticized France-led counterterrorism interventions and supported African-led stability promotion initiatives, such as those led by the G5 Sahel bloc (Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, and Chad). In January 2013, the Turkish Foreign Ministry condemned France’s Operation Serval counterterrorism intervention on the grounds that the UN Security Council had sanctioned only an African-led intervention and that French “unilateral action” would deprive Malians of agency over their political future. Turkish state-aligned media outlets have also expressed concerns about France using counterterrorism operations as a means of extending its influence over its former colonies, such as Mali and Niger.

Although tensions between France and Turkey undoubtedly influence Ankara’s position on Sahel security, Turkey has also taken steps to promote African-led solutions. In September 2017, Turkey engaged with Nigeria on limiting the flow of guns to terrorist groups, such as Boko Haram, as Turkish ports were reportedly used as conduits for these shipments. During his March 2018 visit to Mauritania, Erdogan pledged $5 million in financial assistance to the G5 bloc’s counterterrorism efforts. These initiatives have resulted in closer bilateral security cooperation between Turkey and Sahel countries. On July 26, Turkey signed a military cooperation agreement with Niger, which would allow for bilateral cooperation against the prospective spillover of instability from Libya to West Africa.

Turkey has complemented its security outreach to Sahel countries with highly publicized supplies of humanitarian aid. This soft power campaign has intensified in recent months, as the combined impact of socioeconomic deprivation, political violence, and the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbate the region’s humanitarian crisis. In May, the Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency (TIKA) supplied aid to The Gambia, which aimed to alleviate the country’s food shortages. On June 17, Turkey announced that it would ship a wide array of medical equipment, which included 50,000 surgical masks, 30,000 N95 masks and 2,000 protective glasses, to Niger and Chad, in order to assist their struggle against the COVID-19 pandemic.

In keeping with Turkey’s global efforts to rein in the Gulenists’ influence, Ankara has leveraged its tightening relationships with Sahel countries to encourage them to crack down on Gulenist-affiliated educational institutions. In December 2017, Turkey announced that Senegal would shutter 12 Gulenist-affiliated schools, as bilateral relations between the two countries had improved, and Erdogan emphasized Senegal’s cooperation in the struggle against the Gulenists during his 2018 visit. Chad has also been a receptive partner in Turkey’s anti-Gulenist efforts and Turkish Ambassador to Nigeria Melih Ulueren has courted Abuja’s support for the closure of Gulenist schools, as part of a broader bilateral campaign against terrorism. Turkey has offered educational cooperation as an incentive for closing Gulenist schools. To reward Guinea-Bissau for its compliance on the issue, Turkey signed an educational cooperation agreement with the country during Cavusoglu’s Sept. 10 visit.

Ankara’s geostrategic aims

In addition to aiding Erdogan’s anti-Gulenist campaign, Ankara’s outreach to Sahel countries has geostrategic aims, as Turkey seeks to outflank France and counter the UAE in West Africa. Turkey’s desire to challenge France’s interests, in spite of the power asymmetries between the two countries in the region, was revealed by its response to the Mali coup. In stark contrast to France’s condemnations of Mali’s coup and Ankara’s opposition to the 2013 overthrow of President Mohammed Morsi in Egypt, Turkey emphasized the need to restore democracy and engaged in dialogue with Mali’s transitional authorities.

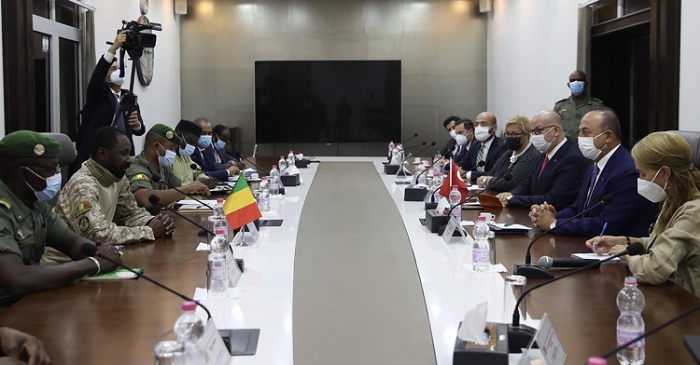

As anti-French protests in Mali erupted after the coup, due to France’s staunch alignment with recently toppled President Ibrahim Boubacar Keita, Cavusoglu met with members of the National Committee for the Salvation of the People, which orchestrated Mali’s coup. In addition to capitalizing on France’s diminished political leverage in Mali, Turkey’s forays into Niger’s mining sector seek to undercut the commercial hegemony of French nuclear power company Areva. As Turkey capitalized on unease among Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) member states about France’s 2013 counterterrorism campaign in Mali and Erdogan distinguished Turkey’s policies from “French neocolonialism” in Niger in that same year, Ankara’s sharpened challenge to Paris’s influence in West Africa is the culmination of a long-standing strategy.

The UAE also views Turkey’s rising influence in the Sahel with trepidation. An Aug. 24 report published by the Emirates Policy Center, a leading Abu Dhabi-based think tank, warned that Turkey’s expanded presence in West Africa “might exacerbate tensions in the region” and expressed concern about Turkey’s alleged sponsorship of terrorism in the Sahel. Turkey’s humanitarian assistance is also aimed at countering similar aid provisions from the UAE, which included a 6 ton shipment of COVID-19-related assistance to Niger and a $2 billion development assistance grant to Mauritania approved in February. As UAE-aligned media outlets have expressed concern that Turkey could establish a military foothold in Niger to assist Libya’s Government of National Accord (GNA), the Sahel is destined to be an emerging theater of Turkey-UAE contestation in the months to come.

Although Turkey’s ability to exert geopolitical influence in the Sahel pales in comparison to established great powers, such as the U.S., France, and China, and emerging powers such as Russia, West Africa is likely to become an increasingly important vector of Ankara’s continental strategy. As tensions between Turkey, France, and the UAE boil over in the eastern Mediterranean and North Africa, we should keep a close eye on a spillover of these hostilities to West Africa in the months ahead.