The Erdogan regime is further shaking up the East Mediterranean geopolitical and energy landscape

Turkey has announced plans to explore a slice of the Mediterranean claimed last year by the Tripoli-based Libyan government, following an air offensive that has pushed the rival forces of warlord Khalifa Haftar out of western Libya.

Turkish energy minister Fatih Donmez said on Sunday that Turkish and Libyan companies will be cooperating on ambitious oil and gas drilling operations in the newly claimed area of sea. The claim is highly controversial—in November last year Ankara and Libya’s internationally recognised Tripoli government signed an agreement extending their economic exclusion zones (EEZs) into territory already claimed by Greece and Cyprus.

The two tracts meet in the middle, overlapping several other countries’ claims and potentially putting another obstacle in the way of plans by Egypt, Cyprus and Israel to build a gas pipeline to Europe. All three have joined with Greece to oppose the Turkey-Libya agreement, which the EU has declared a violation of the Law of the Sea.

Expanded role

Turkey has never before had a major oil concession in Libya, but it expects that to change after giving hefty military support to Tripoli. Its state-run firm Turkish Petroleum has lodged a bid with the Tripoli government for seven exploration blocks off the Libyan coast.

Donmez gave no specific location for the blocks—nor whether they are new or will include taking existing concessions from other IOCs—but said exploration work will begin in September.

It comes as Turkey reinforces its economic and military footprint in Libya. Ankara is building a naval and air base in western Libya to increase its military clout against Haftar. It is also building two Libyan power plants and is in talks about construction and other contracts.

Hurdles remain

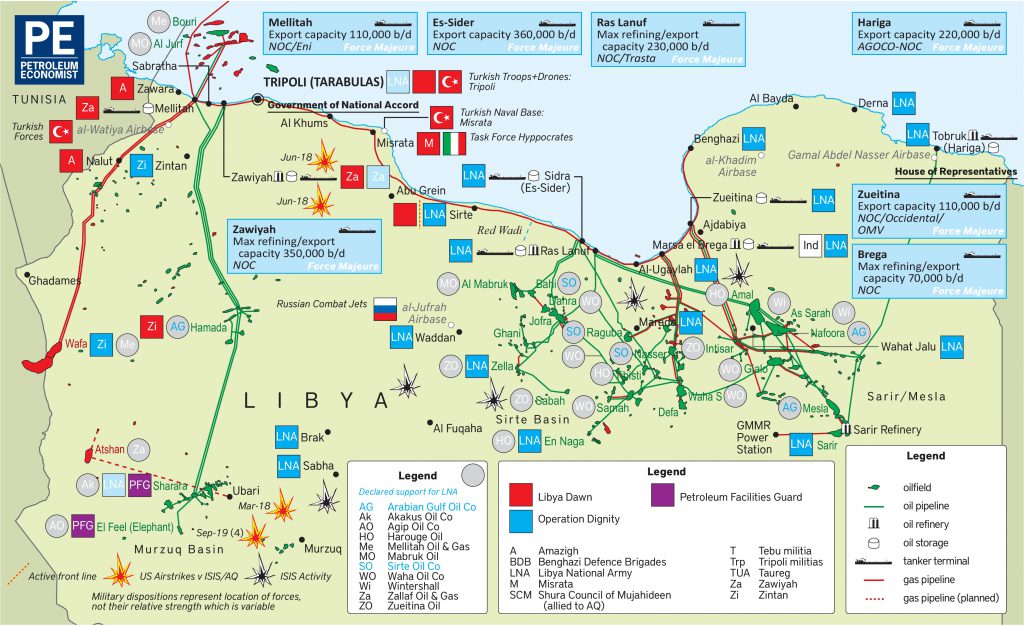

One complication for the regime of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is that the Libyan territorial claim it wants to explore is off the east coast, controlled by Haftar and his allied Tobruk government—a rival administration to the one in Tripoli. Haftar has been vociferous in his opposition to Turkey, accusing it of aiding Islamist elements. And, despite his recent military setbacks, he can still draw on support from allies Egypt, France, Russia and the UAE.

Libya’s oil industry also remains in the doldrums, hamstrung by a blockade of key ports and fields imposed by Haftar in January. Since then, production has fallen from 1.2mn bl/d to c.90,000bl/d, mostly from offshore wells, with export losses now over $5bn.

Haftar’s retreat earlier in the month saw brief re-openings for two south-western oil fields: Sharara, Libya’s largest, and Feel. But, days later, local militias moved into the security vacuum in the south-west, occupying both fields, which were again closed by the National Oil Corporation (NOC).

In a sharp reminder of the chaos bedevilling the country, on 10 June a militia occupied Mellitah, the terminal, operated by Italy’s Eni that ships gas to Italy through the Greenstream pipeline. Eni says the gunmen were persuaded to leave the plant later the same day.

Libya’s civil war, which marks its sixth anniversary in July, is now centred on the struggle for oil, despite question marks over whether the market could absorb the resumption of Libyan production in its current demand-parlous state. Fighting is focused on the border of eastern Libya’s Sirte Basin fields, which, under normal circumstances, account for two-thirds of national production.

Alarmed by the Turkish success, the US has reported Russia deploying 14 fighter bombers to the central Libyan base of Al Jufra to give Haftar air support in ongoing fighting around the coastal town of Sirte. The town is seen by both sides as gateway to the Sirte Basin.