Introduction

Non-state armed groups (NSAGs) pose a thorny policy dilemma for US and European officials trying to stabilize fragile states.1 NSAGs are far from homogenous in their motivations, tactics, and structure, resulting in highly varied roles in either perpetrating or mitigating violence, with many playing a part in both. On one side, NSAGs can create instability by using violence to advance a range of interests, from political influence and financial gain to challenging a central government’s legitimacy or territorial control. Many NSAGs are directly responsible for civilian harm, including perpetrating targeted violence, persecuting, killing and committing brutal abuses against citizens.2 There is no shortage of examples of NSAGs that fit this mold. From Boko Haram in Northeast Nigeria to Katibat Macina in Mali, armed groups have wreaked havoc on the lives of civilians as well as US and European security interests.

In other contexts, however, the picture is not as clear-cut. Some armed groups play a role in maintaining security and protecting citizens from other violent actors, including the state. NSAGs can also provide services, collect taxes, resolve disputes, and establish governance systems in areas where they exercise control. The pandemic has shed light on how the governing authority of NSAGs can be utilized to manage the spread of COVID-19: for example, in Myanmar, non-state armed groups established health checks and restricted travel.3 Depending on the various roles they play in a community, such actors may be viewed as locally legitimate in the eyes of the population. NSAGs, even those with a history of using coercive power, can fill a governance gap and might be the only viable partner for the government and its international supporters trying to stabilize a conflict-affected area.

The dual nature of NSAGs poses the problem of whether, and how, the host government, the United States, and European powers should cooperate with NSAGs as part of a broader stabilization strategy. Critically, NSAGs proliferate in contexts where the social contract between the state and its citizens is broken (or nonexistent). Yet, many stabilization strategies are predicated on the assumption that NSAGs will ultimately be incorporated into political structures, which, by nature, may be corrupt and captured by elites who are more interested in holding power rather than moving toward a democratic system. This presents particular challenges for stakeholders aiming to promote sustainable peace and stability.

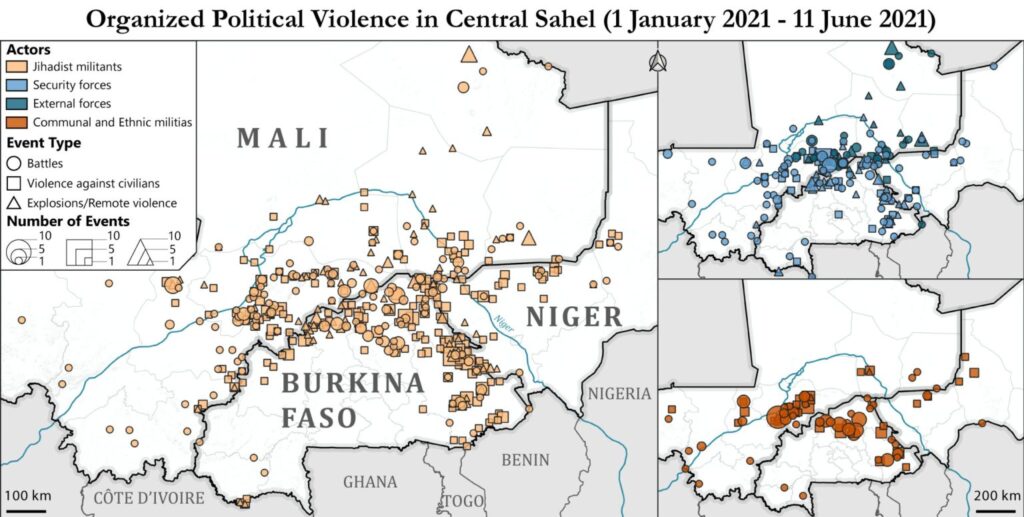

This policy conundrum is particularly pronounced in the Sahel.4 Across this conflict-ridden region, a range of NSAGs—from armed groups holding political motivations and self-defense militias to violent extremist organizations (VEOs)—operate with wide license to advance their interests and have caused conflict rates to skyrocket. In 2021, the Sahel experienced a 70 percent increase in violent incidents carried out by militant Islamist groups (from 1,180 to 2,005 events), just one type of NSAG common to the region, over the previous year.5

But NSAGs are not a conflict-producing scourge everywhere in the Sahel. In some locales where the government—nationally or locally—is weak, corrupt, perceived as illegitimate, or all three, NSAGs often fill a governance void or, at minimum, provide essential services. Witness the Koglweogo in Burkina Faso, which enjoy legitimacy in the eyes of local populations. These “Guardians of the Bush” formed to offset the central government’s inability to quell violent extremist organizations (VEOs), and in some areas provide forms of judicial governance. To the north, in Mali, self-defense groups are common in large swathes of the country. And in Niger, the Izala movement provides security and other forms of governance. These groups are not without their problems. However, the Sahel often offers no easy options for engagement. Solutions will come with difficult trade-offs. Any stabilization approach must account for the legitimacy these groups hold and explore means for engagement, if not outright collaboration or support.

But NSAGs are not a conflict-producing scourge everywhere in the Sahel. (…) However, the Sahel often offers no easy options for engagement. Solutions will come with difficult trade-offs.

Recognizing this challenge, policy makers on both sides of the Atlantic have augmented efforts to understand how NSAGs operate and develop evidence-based approaches to mitigate risks stemming from them. They have done so to confront the NSAG problem generally and for the Sahel specifically. Despite this more concerted focus, however, Washington and its transatlantic allies must do more to enhance their approaches—alone and together.

This policy brief examines how transatlantic cooperation regarding NSAGs can be strengthened. It begins by describing the proliferation of NSAGs generally and the threat they pose to stability in the Sahel specifically. It then explores US and European policies toward engaging NSAGs, highlighting how these frameworks remain underdeveloped on both sides of the Atlantic—and pointing to opportunities for greater coordination. With this overview of the challenge in place, the brief pivots to outlining a three-part solution. The first is a set of criteria the United States and Europe can use to determine which groups are acceptable to engage—generally and as partners in stabilization specifically. This is a thorny policy dilemma but a thicket allies must work through if they are to stabilize key areas of the Sahel. The second is an approach for burden-sharing by establishing a set of common objectives for transatlantic cooperation. The third includes practical options for policy development and parameters for dealing with NSAGs generally and in the Sahel specifically.

The framework is rooted in the principles of the “strategic empowerment” approach to stabilization, which involves supporting local actors that exercise governing authority in a citizen-centric manner and align with U.S. values and standards. 6

Fragile states offer no optimal solutions, but strategic empowerment is the best available option and well suited for the increasingly contested nature of stabilization. “Contested stabilization” is defined as “situations where international actors pursue their own contradictory strategic objectives in a fragile or conflict-affected state. It is the stabilization corollary to a proxy war: Actors engage in stabilization activities—diplomacy and other assistance, to empower local actors and systems they can influence—with the aim of improving their own core interests, gaining access to emerging markets or resources, antagonizing adversaries, and expanding their perceived sphere of influence.” 7