By African Investigative Publishing Collective and ZAM team: David Dembélé (Mali), Theophilus Abbah (Nigeria), Charles Mafa and John Mukela (Zambia), T. Kaiwonda Gaye* (Liberia), Estacio Valoi (Mozambique), Purity Mukami with Africa Uncensored, Kenya

“You must be very careful,” says the lawyer over the phone to the local reporter. “This is a dark and sensitive dossier. You mustn’t mess with it. My client is connected to the very top in this country and he has been doing business with most important people over the past thirty-five years. As Africans, we have to do things the African way. You must not listen to these foreign whites who sent you to investigate my client.” It is a puzzling remark, because his client is white and originally from Western Europe. But the fact that the kleptocrat ruler of the country in question and his political elite have done business with him for so long has made him African, the lawyer explains. When he talks of ‘these whites’ he does not mean whites like his client, but whites like the ones in (partly Europe-based) ZAM Magazine, who, together with the local reporter, are trying to unearth some detail about this ‘dark and sensitive’ very African way of doing things.

It must be noted that the lawyer, instead of saying ‘African,’ used the name of his country. He spoke to the reporter as fellow nationals of a specific African country and referred to his nation’s way of doing things. But in essence, the cliché is the same. It has been used by western and other international business people to justify their sometimes less than savoury business on the continent for decades. “We have to pay bribes here, it is the African way,” they would say, emphasizing that they would much prefer doing business cleanly and properly, but that this was, alas, simply impossible.

There was and is sometimes a bit of truth in that. Local kleptocrats -as shown in our previous transnational investigation, African Oligarchs (1)- do in fact often insist on partnerships that feed corruption. And the country where the above mentioned lawyer lives ranks among the top corrupt countries in the world. (It is part of the reason why we can’t as yet write openly about where and how we exactly met this lawyer, since it might endanger the reporter on the ground. We hope to publish this part, the seventh country, in the near future, when we are assured of his safety.)

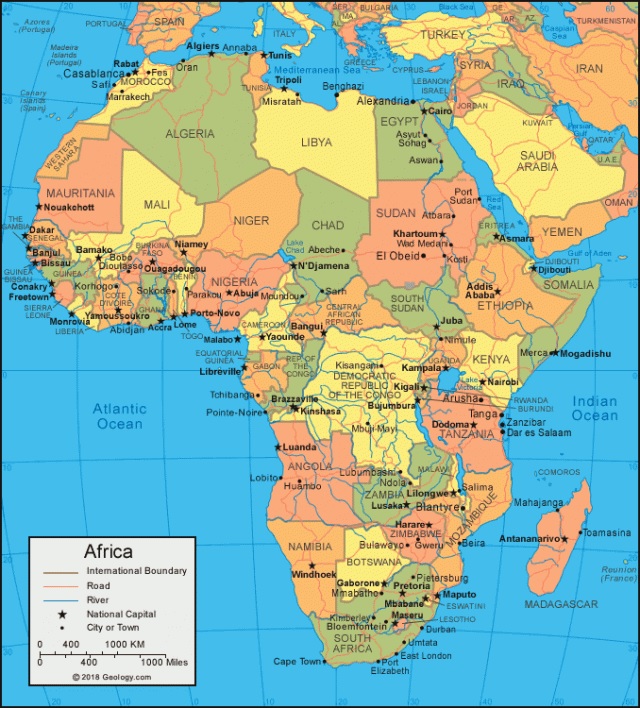

This transnational investigation has been all about middlemen such as the one who has employed this lawyer: international businesspeople, bankers, accountants, lawyers and sometimes even diplomats, who are “connected to the very top.” Results from our exploration, over the past nine months, in vastly different African countries, show that African oligarchs from Mozambique to Mali, and from Liberia to Kenya, are assisted by such international and local business connectors in joint efforts to make money from natural resource wealth and state budgets. Whereas many of these business deals and transactions are legal in terms of the letter of the law -as are, for example, many of the off shore accounts unearthed by the Panama Papers- what we discovered sheds a spotlight on the kleptocracies’ mechanisms. Going deep into the belly of ruling circles in countries where the vast majority of citizens are desperately poor, we discovered how local and international business partners assist presidents, ministers and ruling party bureaucrats work to convert political power, often via access to natural resources, into personal financial reserves and assets.

Selling out

The outcomes of the investigation underline once again that the stereotype of foreign multinationals that ‘take wealth’ from Africa needs to be nuanced. The problem of African wealth extraction does not come from ‘outside’ alone. While ‘African Oligarchs’ showed that ruling elites in many cases actively sell out their own countries, ‘The Associates,’ as we have called the new project, shows how they do it and in partnership with whom. Politicians, after all, are not always financially savvy; those who want to loot their countries do need their bankers, lawyers, accountants and business friends. The arrangement always concerns one or more state officials or politicians who dish out the contracts, the licenses and the opportunities; the associates provide the business and financial channels, and pay back with a share.

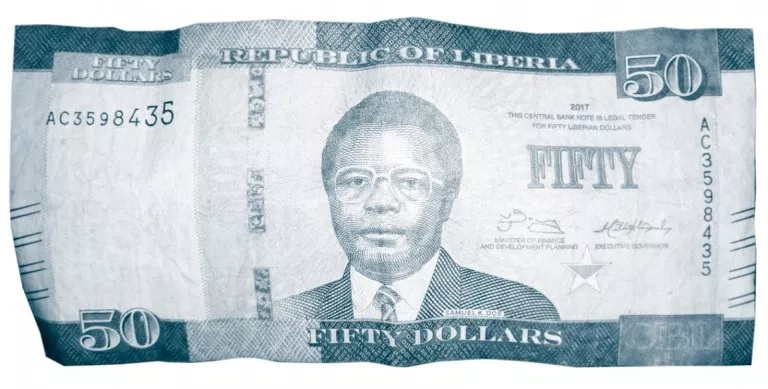

Associates of kleptocratic governments can be foreign or local. In Kenya, politically connected business people were found to have made millions out of a failed dam project that left poor farming communities in the Rift Valley to battle with dry and unsafe water sources. At the top, the politicians who gave the dam contract to a bankrupt Italian company created the opportunity for local associates to benefit from equally useless subcontracts. Huge payments were made from state coffers to these connected business people in exchange for questionable services to a project that so far left behind little more than rubble. In Liberia, equally local, but money-savvy presidential associates-turned-ministers got their hands on newly printed banknotes as well as on a large part of the country’s foreign dollar reserves. Among the methods used were intricate financial exchange exercises that resulted in sky-rocketing inflation and food prices as well as empty bank vaults. In Mozambique, a Chinese company at the root of devastating deforestation received even more licenses from its friends in the state so that they could move on to deplete its seas of fish. As a result, while local fishermen and villages are left without food and income, the company and its associated Mozambican ministers -and a general- benefit.

The West African nation of Mali, meanwhile, forks out double to triple the price for the bottles of mineral water it purchases through ‘anonymous middlemen’ from a friendly businessman associate, who in turns deposits much of his large income in Panama. In Nigeria, a region that could have prospered as a result of large-scale steel manufacturing, has been left abandoned and poor as ever because four decades of politicians, in successive governments, allowed it to be looted: each time by a different set of business associates. Apart from the first six months of its existence, the plant has not produced any steel.

STREAMER The same company at the root of devastating deforestation was now depleting the seas of fish

The investigation found gradual differences between the countries. In Kenya, for example, where professional media and activists over the years have achieved more transparency in state affairs and an incipient tradition of political accountability, it is becoming less easy for corrupt officials and businesspeople to get away with cheating citizens: all companies involved in the questionable Rift Valley dam contract are now under investigation by the law enforcement authorities. In Nigeria, in similar developments, parliamentarians are pressuring the government to finally show leadership and governance with regard to the steel project. The politicians who rule Mozambique have as yet not shown that they want to change their ‘wealth-sharing’ ways, but they are currently being dragged into an era of accountability with the arrest of former Finance Minister Manuel Chang and charges against Chang’s associates in the Swiss bank Credit Suisse in a US$ two billion dollar loan fraud.

In contrast, there is still a long way to go with regard to other countries in this investigation. In Mali, officials simply put the phone down when they are asked about the percentages they receive from overbilling suppliers. In Liberia, militias threaten those who “make problems” for the president and a series of fatal car accidents recently killed three whistle blowers in the newly printed banknotes scandal.

No ‘rotten apples’

What all the countries where we worked did have in common, is that the corruption was not a simple crime committed by individual ‘rotten apples.’ If that were so, the dismissal and arrest of such apples -be they politicians, bureaucrats or business associates- would have an impact. But on its own, arrests were not enough. It was noted that many politicians have gone to jail for corruption in Cameroon, -often after falling out of favour with President Biya- , but the system whereby rulers personally benefit from state resources has stayed in place throughout. In other countries where arrests for corruption have taken place, like in Mozambique and Zambia (where the Minister of Public Works was recently arrested), the arrests have also not (yet) changed the system whereby state structures facilitate the access of the politically powerful to state coffers and contracts. Even democratic, or democratic-looking, elections were not found to make much difference: President Weah in Liberia was elected democratically, but the opaque governance where paper work is full of ‘discrepancies’ and nobody is held accountable for missing money, remains. It appears to be only when social protest results in practical transparency measures, accountability and impartial law enforcement, that systemic changes get a chance to develop.

In most of the countries we investigated, the systems of corruption are still largely in place. Law enforcement authorities still often hesitate to investigate the very powerful. It is the reason why good civil servants -our very good sources- fear for their jobs and livelihood when they speak out. In Mozambique, we found that while a mayor can allow foreign fishing companies to rent his own house for their fish-packing, an anti-poaching unit member is scared to mention his name. The fishing companies have licenses after all; with the state littered with officials doing the bidding of ‘those above,’ the state’s administration itself is used to legalise wrong practices. Similarly, Zambia’s President Edgar Lungu has legally signed away environmental protection for Lusaka’s forest, thereby severely endangering the river water artery for the capital city. The act preceded the construction by Chinese and local associates of luxury houses for the local elite, eager to occupy its “dream homes” in the nature reserve.

The elite wants ‘dream homes’ in the forest

As a result of the construction in the forest and the pollution of the river, Lusaka’s ordinary citizens may be left with only sewage-contaminated ground water to drink. Together with the Kenyan dam example, the now sky-high food prices in Liberia as a result of large numbers of new banknotes untraceably entering the economy, the starving Mozambican fishermen, and the despairing people of Mali’s north, our case studies paint a picture of what the wealth gap in Africa increasingly looks like: a citizenry without clean water or food reserves, whilst the elite live their ‘noble life’ -in the words of the developers- in a place called Kingsland City.

But civil society protests are growing. Liberia’s opposition, together with several citizen groups, has called for a day of protest against corruption and high food prices on 7 June. In Zambia, civil organisations have taken the government to court to protect their water supply. In Nigeria, parliamentarians, NGOs and journalists have called for a stop on the corrupt parasiting of the steel plant and in Kenya, persistent efforts by good civil servants, journalists and transparency activists are slowly opening up the truth about the state’s finances.

International transparency

It must be noted that international investigations and good governance initiatives have played an important role in uncovering assets and sometimes even judicial proceedings against dictators. In 2017, France confiscated a yacht and other assets of Teodorin Nguema, Vice President of Equatorial Guinea and son of its kleptocrat president Obiang Nguema, whilst simultaneously convicting Teodorin -in absentia- of fraud. One year later, the Ontario Securities Commission in Canada, fined a number of mining company directors for false accounting in their deals in the DRC. United States law enforcement agencies helped bring about the arrest of Mozambique’s Finance Minister Chang, who had channeled fraudulent loan transactions partly through banks in New York. The development organization USAID helped bring to light the banknotes shenanigans in Liberia by insisting on a public investigation. International transparency institutions like EITI (the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative) have helped unearth information about kleptocrats’ business associates who avoid paying tax in Mali and Cameroon. Corrupt Nigerian politicians and their associate bankers have been held accountable in the United Kingdom.

Perhaps the good news is that the ‘African way’ cliché is increasingly outdated. African citizens, activists, journalists and thousands of ethical, hard-working civil servants within governments and states welcome the international spotlight, investigations, and arrests of those implicated in theft from their countries. They protest corruption and demand transparency, accountability and good governance.

Still, much needs to be done. Support for African investigative journalists as they continue expose wrongdoing is once again noted as an important need. During this investigation, three members of our team were threatened. Besides the one reporter being told that he must not “mess” with the business he was investigating, Estacio Valoi received death threats in Mozambique while he was held by the army and his laptop, phone and cameras were searched, while our Liberian colleague operates amid so much fear and unsafety that we had to use a pseudonym for him in this report.