One of the main long-term consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is the restructuring of export flows in the global oil market. This will have direct consequences for Middle Eastern players, forcing them to choose whether to compete with Russia and each other or continue to coordinate their efforts.

In spite of the rumors that Russia might be suspended from the OPEC+ deal, the current cooperation between Moscow and other oil producers may still survive and continue beyond September 2022, when the agreement on production cuts expires, although the chances of this happening are decreasing. There are ongoing concerns about the stability of the oil market and keeping the cartel together is the only way to manage it. Even though its production capacity is declining, Russia remains an important player and one whose role in Asia, a key consumer market for Gulf oil producers, could potentially increase. If there were questions during the first weeks of the conflict in Ukraine about whether the threat of sanctions and logistical bottlenecks would allow Moscow to redirect its oil exports from Europe to Asia, by now the answer is clear: yes, it can. For example, in the case of oil terminals in the west of Russia, the volume of oil supplies going to the “East” increased from 0.14 million barrels per day (mbpd) in January 2022 to 0.9 mbpd in April and 0.55 mbpd in May.

Putting aside its initial fears and hesitation, India turned out to be the main buyer of extra volumes of Russian oil. From almost zero in February, its imports rose to 0.9mbpd in May; in previous years its average imports did not exceed 0.2mbpd. China quickly followed India’s example. Interest in additional supplies emerged not only from traditional buyers of Russian hydrocarbons among China’s independent oil refining companies (so-called teapots), but also from major Chinese players affiliated with the government, which had initially said they would not be interested in buying Russian oil due to the threat of sanctions. However, as statistics show, after an initial decline in Russian oil exports to China from 1.7mbpd in January to 1.4mbpd in February, volumes began growing again, reaching 1.6mbpd in April and almost 2mbpd in May. In April and May of this year, Russian seaborn oil supplies to China reached their highest levels since March 2020, exceeding 1mbpd, against an average of 0.8mbpd in 2021. Moreover, demand for Russian oil is not limited to China and India, with Indonesia and Sri Lanka both showing an interest as well.

The first dose is free

Several factors support the growth of Russian oil supplies to Asia. The most important one is the unprecedented discounts that Russian producers are offering their customers to compensate for the potential risks and costs of purchasing politically toxic oil. According to various estimates, this discount may be as high as $25-35 per barrel, which attracts profit-minded refiners that have already significantly boosted their margins and countries that are experiencing economic difficulties and cannot afford to purchase oil at the high official price. Russia’s partial loss of the petrochemical market may also benefit the oil trade: Russian oil may be in demand as a feedstock in those countries that have tried to replace Russia and increase their exports in the markets for fuel and other petrochemical products. Thirdly, Moscow should be grateful to Tehran, which previously allowed Asian consumers to develop a number of techniques to circumvent sanctions to buy Iranian oil. These same techniques are now being used by Beijing and others to adjust their oil trade with Russia in light of the new realities. At the same time, in terms of the oil volumes available, their quality, and in some cases their greater proximity, Russian hydrocarbons appear be more attractive for Asian consumers than Iranian ones. Finally, Moscow is ready to pay the costs associated with the supply of oil to Asian markets and quickly learns from its mistakes. This extends not only to its willingness to provide discounts, but also to take on both the risks and costs associated with paying for ship insurance, owning its own tanker fleet, using low-tonnage carriers, as well as trading oil “from tanker to tanker.” Ultimately, despite all of the associated costs, today’s high oil prices allow Moscow to remain in profit.

Winners and losers

However, there are also losers from the current market dynamics, including oil producers in the Gulf. Iran was the first to suffer. Russia challenged its position in the gray market for sanctioned oil. As already noted, Russian hydrocarbons have a number of undeniable advantages for China, including the fact that the restrictions on Russian oil are not as strict as those on Iranian oil. It is difficult to judge Iran’s losses, since there is no accurate accounting of how much of its oil bypasses sanctions. However, the Iranians’ pained reaction to the inflow of Russian oil certainly says something about how much income they have lost. Moreover, it is not just about oil but also petrochemical products. For example, Russian liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) has become a significant competitor to Iranian LPG in Turkey, Pakistan, and Afghanistan.

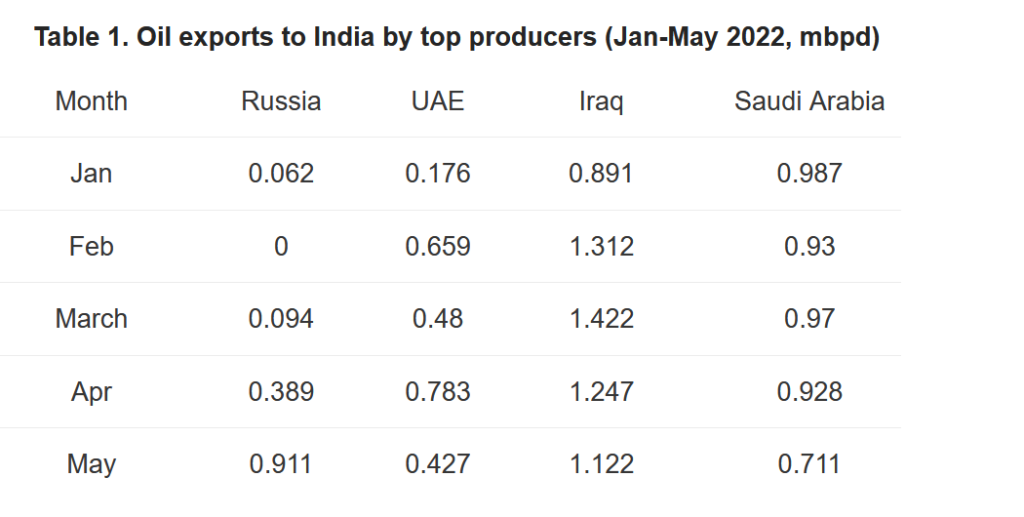

In the Indian market, Russian oil has challenged the positions of other Gulf producers, including the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and especially Iraq. By May 2022, all three countries had lost a substantial volume of supplies to Moscow (see Table 1).

Russian oil may also present a threat to Saudi interests in the Chinese market, although so far the volume of Saudi supplies to China has been growing steadily. However, according to some experts, Oman will be the main victim of the influx of Russian Urals oil to China.

All of these factors have forced the Gulf countries to reconsider their pricing policies. Thus, in April, Iraq was the first to cut its oil prices. In May, other Gulf producers followed suit. Interestingly, Russian prices turned out to be more influential than other factors affecting the market, such as the possibility of a gradual easing of quarantine restrictions in China, that in theory should have pushed oil prices upward.

Brave new world

The bad news for the Gulf states is that this situation is becoming the new reality. Even though the situation may have been created artificially, when some countries, for political reasons and contrary to their economic interests, voluntarily refused to purchase Russian oil, its impact is all too real, creating supply shortages in some markets and potential surpluses in others. There have been similar precedents before, but they were more localized in nature, as in the case of Venezuela or Iran, and the conditions were slightly different. In Russia’s case, the restrictions on oil purchases are being used against one of the main players in the market, affecting a significant amount of oil when there is already an existing undersupply. Moreover, this trend is obviously long term. The European desire to avoid dependence on Russian oil is unlikely to change. Russia will also not be able to immediately redirect all of its oil to Asia and find buyers for it, as evidenced by the growing volume of Russian oil reserves accumulating in storage and on tankers. This means that, at least in the medium term, Moscow will have certain reserves of hydrocarbons that it can use to affect the market’s balance. Russian oil will also be a wild card as part of it is now sold secretly, under other names, thus making it difficult to track. There are already rumors about schemes Russia is using to channel its oil exports to third countries through the Gulf states, Asia, and even the EU.

The war unleashed by Vladimir Putin gave rise to a restructuring of oil market flows and created new sources of uncertainty that will last at least until the conflict ends and relations improve. That is not likely to happen soon and the market seems to be beginning to recognize the long-term nature of the current situation. Thus, companies based in East and Southeast Asia, such as Shandong Port International Trade Group or Livna Shipping, are replacing the previous traders of Russian oil that were mainly based in Europe. Gulf producers are no longer silent about their problems and are obviously unhappy that political factors have created a serious imbalance in oil exports flows — a point clearly articulated by UAE Oil Minister Suhail al-Mazroui in early May. Gradually, everyone seems to have come to the same conclusion: Sanctioned Russian oil is becoming a new reality in Asian oil markets and it must be reckoned with. Some players, like Iran, are trying to find a way to co-exist with Russia, hoping to divide the market for “gray” oil. Others, like Saudi Arabia and its partners, can presumably expect to work with Moscow within the framework of OPEC+, although some cartel members are in favor of greater competition with Moscow for oil markets. None of them, however, should doubt that Russia will remain an important player in the oil market, at least for the foreseeable future.