Viruses worm their way into living cells, change the structure of the host cells from within, take over the cells’ reproductive process, use the cells’ own machinery to make copies of themselves, and conquer and kill the host. Routine antibiotics do not work while fighting viruses. You need a molecule that prevents the process by which the virus duplicates itself, or you need a vaccine to make your cells vigilant to such viruses and treat it as a foreign object.

The Chinese state uses trade, technology, and bribery to worm its way into democracies, changes host countries from within, expands its span of attack, and conquers host nations. Since it uses the strengths of the host—democratic institutions, freedoms, open societies, independent judiciary, universities, media, and a vocal not-for-profit sector—to destroy the host, the more the host strengthens itself, the more vulnerable it gets to Chinese attacks.

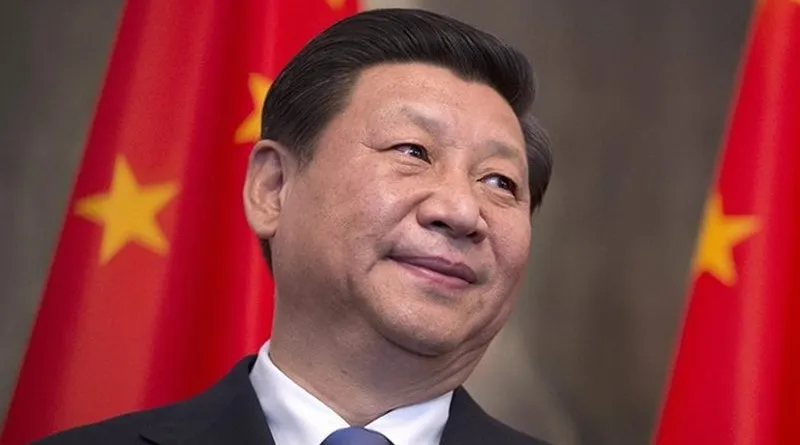

One democracy after another, one country at a time, under China’s Chairman of Everything, Xi Jinping, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—to which is appended a state called China—is on a conquest. Using the Whole-of-State approach—that is, by means of state and non-state actors such as companies, universities, cultural organisations, and even ordinary citizens—the CCP hopes to entice democracies with cheap goods and services to gain strategic advantages, with which to smother the values of the host nations.

Hiding in plain sight, standing under the bright citadels of knowledge, and promoting hostile forces in the garb of championing free speech, the narrative-driving elites in universities and media remain one of the biggest enablers of Chinese interference democracies across the world. On its part, the Chinese playbook that weaponises information and knowledge to gain strategic strength, by attacking these chinks in the armours and protections of democracies, has been in play for decades. That’s changing, one country at a time.

Eight years after the United Kingdom’s Intelligence and Security Committee of Parliament alerted its citizens about the threat of Chinese intrusions, the UK lawmakers are waking up. In its 13 July 2023 report, the Committee, under Julian Lewis, has presented a 207-page account that exposes the security vulnerabilities of the UK by China. While the report showcases intrusions through the government, by influencing elections, using industry and technology, and civil nuclear energy, this essay focusses on the role of and collusion by the UK academia and the UK media.

In China’s lust to achieve political influence and economic advantage, “the UK’s academic institutions provide a rich feeding ground,” the report states. CCP hopes to control the “narrative of debate about China within UK universities by exerting influence over institutions, individual UK academics and Chinese students; and obtaining Intellectual Property (IP) by directing or stealing UK academic research in order to build, or short-cut to, Chinese expertise.” This is accentuated when dealing with what China deems “Five Poisons”—Taiwanese independence, Tibetan independence, Xinjiang separatists, the Chinese democracy movement, and the Falun Gong.

There are six threats from China to the UK that pass through and use academia as cover. First, the number of students from China—more than 120,000 in 2019 compared to just 27,000 from the next largest contingent from India—is the highest. As a result, the ratio of university income from fees to public funding has reversed from 28:72 to 73:27, of which Chinese students generated about £600 million (US$ 785 million). But these are innocent financial statistics.

What should be more worrying for the UK is that each of these 120,000 students are required by Chinese law to provide assistance to the Chinese Intelligence Services. In other words, each of these students is potentially a spy. There are five Chinese laws that ensure this—the Counter-espionage Law (2014), the National Security Law (2015), the National Cybersecurity Law (2016), the National Intelligence Law (2017), and the Personal Information Protection Law (2021). Article 7 of the National Intelligence Law, for instance, demands that “All organisations and citizens shall support, assist, and cooperate with national intelligence efforts.” As do Articles 9, 12, and 14.

Second, institutional capture is only a necessary condition for Chinese influence—it is not sufficient to ensure infiltration. For the latter, China targets individual academics to ensure they act in CCP’s best interests, “either through professional inducements or, if that doesn’t work, by intimidation.” These include research funding or travel opportunities to vice chancellors or student bodies getting phone calls to “discourage universities from allowing speakers on issues like Tibet or Xinjiang.” Further, CCP’s experience in weaponising trade and debt has been extrapolated to weaponising academia. “Research for academics entering China is weaponised. You say something that they don’t like, they deny you a visa,” the report cites Prof Steve Tsang of the China Institute at the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London.

Third, those Chinese students who do not take up spying activities for CCP are threatened, often with death. In November 2019, a student who was photographed in Edinburgh supporting democracy in Hong Kong, was photographed at the airport while escorting his mother. Both pictures were circulated on Weibo. It said, “Brothers from Chengdu, beat him to death,” and gave the flight number and a call for him to be arrested by police or assaulted by citizens. “It was shared 10,000 times.” A Hong Kong student at the University of Sheffield said that against a few hundred students from Hong Kong, there were 4,000 Chinese students. “It’s the fear of what they might do that scares us. We are sure we will be on watch lists when we go home,” a student said.

Fourth, it is not merely universities that are attacked by the CCP—think tanks and non-governmental organisations face the same tactics to push the China narrative. This is no different from think tanks of the West, for whom lobbying for an ideology or politics is par for the course. But when Chinese tactics cross the threshold of ‘interference’, by weaponising visas or holding a threat for Chinese scholars when they return to China for instance, it becomes a security problem.

Fifth, stealing intellectual property from academia. “In our role trying to defend the UK from cyber-attacks, China’s ambitions to steal IP is one of the principal things that we worry about,” Chief Executive Officer of the National Cyber Security Centre said. Three years earlier, through a 29 May 2020 proclamation, the United States under President Donald Trump had called out this Chinese theft of intellectual property by students working for the Chinese military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), and subjected their entry to “restrictions, limitations, and exceptions.” Two years before that, a 26 October 2018 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute had alerted the UK about the PLA sending 500 military scientists each to the UK and the US academic institutions between 2007 and 2017. “Chinese Talent Programme participants have pleaded guilty or have been convicted of offences, including economic espionage and theft of trade secrets, export-control law violations, and grant and tax fraud,” the Intelligence Committee states.

And sixth, using the UK research to support Chinese interests. Theft aside, “China directs, funds and collaborates on research – in particular that which might benefit the Chinese military.” These reside in plain sight under benign terms such as goods, software, technology, documents, and diagrams “which can be used for both civil and military applications.” After completing his PhD at the University of Manchester—where, following Xi Jinping’s visit, a partnership was created to “accelerate the application of graphene in the aviation industry”—scholar Huang Xianjun is now a researcher at China’s National University of Defence Technology, working on key defence projects for the PLA.

Much of this is known through anecdotal evidence. But now, in several universities spread across nations, a China-focussed academic centre, be it in the area of technology or as part of cultural Confucius institutes, needs deeper scrutiny. The smoky data exhaust from such ‘collaborations’ is clearly pointing to the strategic ambitions of the Chinese state, from the CCP to the PLA. On the other side, Western individual academics have become willing pawns for a few pieces of renminbi. They are championing the cause of the PLA, the CCP, and Xi Jinping at the cost of their nations. Calling them ‘useful idiots’ is giving them a free pass. Since these are allegedly among the smartest people around, ‘conscious conspirators’ if not ‘conscious collaborators’ would be a more accurate description.