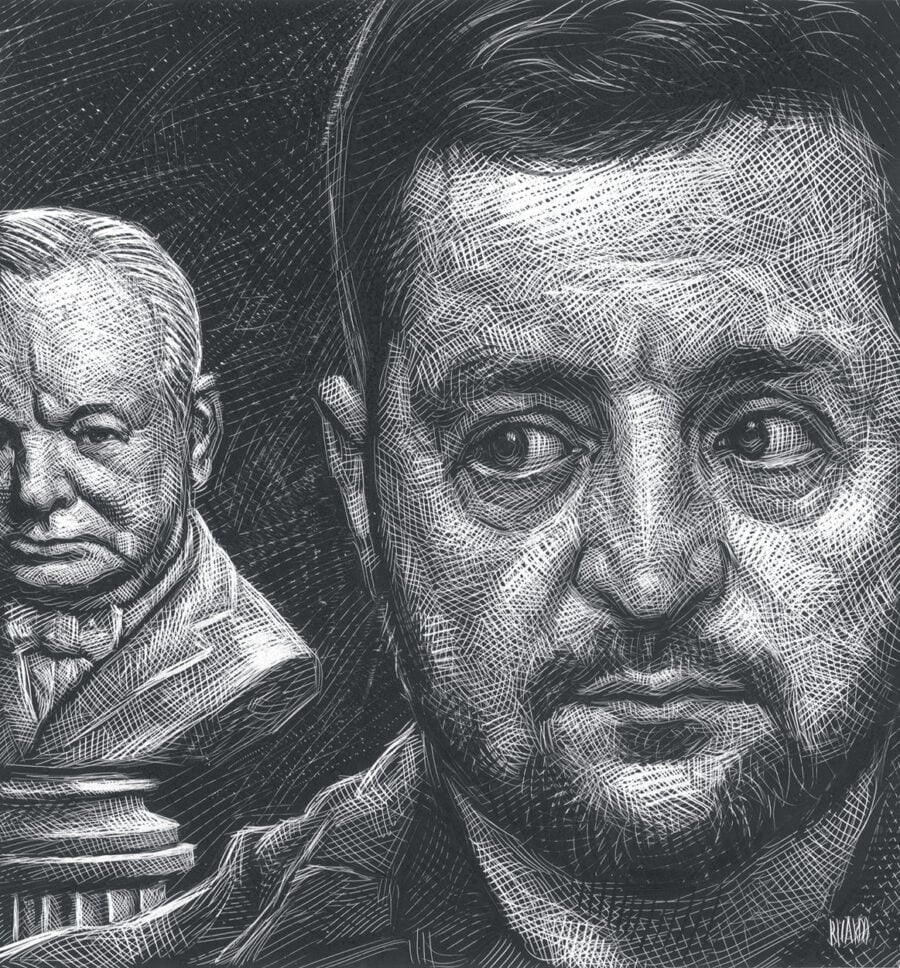

In December 2022, Time magazine named the Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky its Person of the Year. The reasons seemed obvious: When Russia invaded in February of that year, few thought that Ukraine would survive more than a week, or that its president would remain at his post in Kyiv. But Zelensky, who had been a comedian and actor before his unlikely landslide election victory in 2019, defied Russian airstrikes and mobilized his countrymen, rebuffing Western offers of evacuation: “I need ammunition, not a ride.” His unexpected courage helped to rally Ukrainian forces against Russia’s northern thrust. He also reminded many of the two-time Man of the Year—in 1940 and 1949—Winston Churchill. Also known for defending his country against the aggression of an authoritarian leader, Churchill was, as Time’s tribute noted, “the historical figure to whom [Zelensky] has most often been compared in recent months.”

Comparisons between Zelensky and Churchill are apt, but not only for the reasons that those making them intend. The British Bulldog’s legacy is in fact quite mixed. His biographer Geoffrey Wheatcroft rightly reminds us that a balanced assessment of Churchill must acknowledge “the one irredeemably sublime moment in his life, when he saved his country and saved freedom.” But his actions in Britain’s “finest hour” do not negate the many missteps he made over the course of his political career. As more critical accounts of Churchill’s tenure have emerged—among the best are Robert Rhodes James’s Churchill: A Study in Failure, 1900–1939 and John Charmley’s Churchill: The End of Glory—it has become harder to ignore his many blunders. These include the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign during World War I (which resulted in around 200,000 casualties) and several miscalculations during the interwar years, when he took a relatively benign view of Mussolini, Franco, and even Hitler, then pursued a mostly one-sided relationship with Stalin (“I like him the more I see him,” he confessed to his wife). Notwithstanding his resolve in the face of a potential German invasion, even his strategizing during World War II was far from masterful. Churchill badly underestimated the Japanese threat and then, in the face of the siege of Singapore, demanded that British forces fight to the bitter end. His cold-blooded attack on the French fleet in Mers-el-Kébir in July 1940 not only constituted shabby treatment of an erstwhile ally but was based on the false assumption that Vichy France planned to turn its ships over to the Axis powers.

Like Churchill, Zelensky deserves a place in history for his actions during a perilous moment. The Ukrainian leader showed great physical courage by staying in Kyiv when it appeared that the Russian Army would seize the capital. But physical courage is not the only thing Zelensky will need to steer his country out of its current conflict. And like Churchill, Zelensky’s track record before and since his finest hour is checkered at best.

Born in the eastern Ukraine mining city of Kryvyi Rih in 1978, Zelensky is an improbable successor to Churchill. His father was a professor and his mother an engineer. As a teenager, he began competing in comedy contests modeled after the popular Russian television show KVN. This set the stage for his successful TV series Servant of the People, in which he played a simple schoolteacher who becomes a reformist president of Ukraine.

Zelensky has a history of defying the odds. When he announced his candidacy for president in 2018, few anticipated that he would defeat Petro Poroshenko, the incumbent, or edge out Yulia Tymoshenko, a former prime minister and the darling of the Orange Revolution. He not only prevailed over these veteran politicians but did so handily, winning more than 70 percent of the vote in the second round of elections. Before the ticker tape had settled, he dissolved parliament and called elections, in which his party—Servant of the People, named after the TV program—gained an outright majority. Zelensky went from dark horse to powerful president in the blink of an eye.

Three main factors account for Zelensky’s rapid rise. First, he was considered to be above the fray. Though anti-Semitism is still rampant in the post-Soviet states, the Zelenskys, as a Russian-speaking Jewish family, straddled the country’s ethnolinguistic fault lines. As a Russian speaker, Zelensky could communicate across the border with Russia and could point to his friends and relatives in the eastern, predominantly Russian-speaking region known as the Donbas as evidence of his ability to bridge that divide. Zelensky had also wisely stayed out of the contentious Maidan Revolution in 2014. Neither he nor his close colleagues were active in the movement to overthrow Ukraine’s Russia-friendly president Viktor Yanukovych, which deeply divided the country. Instead, Zelensky aimed his barbs at targets across the political spectrum, and even performed with his comedy troupe in the Donbas city of Horlivka during the post-Maidan uprising.

Zelensky’s second advantage was timing. His meteoric ascent reflected widespread disenchantment with business as usual—particularly corruption and the war in the Donbas, which had taken the lives of some thirteen thousand people. By 2019, public distrust of the elite was deep-seated. A vote for Zelensky was seen as both a repudiation of the establishment and an act of faith in a brighter future.

Finally, Zelensky was careful to keep his agenda quite vague, so as to avoid disturbing the image that voters had of him as an actor or backing himself into a corner. His biographer Serhii Rudenko has suggested that his voters imagined themselves electing the protagonist of Servant of the People, rather than Zelensky himself. Writing on the eve of the election in the New York Times, the journalist Alisa Sopova explained that keeping his political slate clean was “an asset for him—as well as a canvas onto which people can paint whatever they want.”

No wonder Zelensky’s supporters initially believed he would bring an end to the two scourges plaguing the Ukrainian body politic: its rampant corruption and the festering civil war in the Donbas. That he has failed, so far, to solve either problem constitutes the great missed opportunity of the Zelensky presidency, and has much to do with the tragic predicament that Ukraine finds itself in today.

Zelensky’s resolve to root out corruption flagged early in his term. There are, to be sure, structural features of post-Soviet states—a dependence on only a few industries and natural resources; the legacy of state-owned enterprises—that have long empowered oligarchs to manipulate the political system. But a more recent development is just as central to Ukraine’s endemic corruption. In 2014, during the Maidan Revolution, Yanukovych was toppled by mass protests in which a small group of ultranationalists pushed an extreme agenda. These forces subsequently regarded any move against Yanukovych’s anti-Russian successor Poroshenko as a betrayal of the revolution. In turn, many Ukrainian oligarchs found that wrapping themselves in the Maidan battle flag helped to conceal their nefarious business activities.

On television, Zelensky played an incorruptible teacher turned president, but the reality is more complicated. One of his original backers was Ihor Kolomoisky, a Ukrainian billionaire with a controlling interest in the television channel that aired Zelensky’s show, who would later be placed on the U.S. sanctions list for alleged fraud. Despite attempting to distance himself from his former patron, Zelensky has never been able to make a clean break with him. Indeed, Zelensky and his associates have been linked by journalists to some $40 million in offshore accounts associated with Kolomoisky’s notorious PrivatBank.

Another sign that Zelensky was not going to clean out Ukraine’s Augean stables came in March 2020, when he fired the prime minister, Oleksiy Honcharuk, whose anticorruption efforts were creating waves. An assassination attempt on Zelensky’s adviser Serhiy Shefir, reportedly due to anticorruption efforts, seems to have further reinforced the steep cost of pursuing good governance. This January, amid continued allegations of corruption, several high-ranking ministers were forced out, along with a raft of regional governors.

Zelensky’s commitment to end the war in the Donbas has suffered a similar fate. While the prospect of settling things through peaceful negotiation looks increasingly remote after more than a year of all-out war, at the beginning of Zelensky’s administration conditions were far more favorable. According to research collected by the San Diego State University political scientist Mikhail Alexseev, around 70 percent of Ukrainian poll respondents in the years leading up to the 2019 presidential election said that ending the war in the Donbas was their “number one concern.” Voters in the eastern region turned out in droves for Zelensky in the second round of presidential voting in April 2019. That November, a poll administered by the Democratic Initiatives Foundation found that 73 percent of respondents supported a negotiated settlement.

Russia also seemed amenable to negotiations. A spokesman for the Russian president Vladimir Putin said that the country’s primary interest in the 2019 Ukrainian election was to see a candidate win who would work to settle the conflict. Putin maintained through 2021 that “the Donbas is an internal issue of the Ukrainian state,” and waited until the eve of the February 2022 “special military operation” to support the independence of the rebellious Donbas oblasts of Luhansk and Donetsk. This suggests that Putin’s initial strategy was to ensure that pro-Russian Ukrainians retained veto power to counterbalance Kyiv’s increasingly Western tilt. The New York Times quoted the former president of Kazakhstan Nursultan Nazarbayev’s claim that Russia would have traded the Donbas for “other things”—the promise that Ukraine would not join NATO, for example.

Zelensky initially seemed inclined to pursue a negotiated settlement along lines worked out in a series of meetings in Minsk in 2014 and 2015. The so-called Minsk process began in the fall of 2014, once the war in the Donbas had shifted in favor of the separatist rebels (and their Russian backers). The Minsk agreements, signed in September 2014 and February 2015, mandated a ceasefire, withdrawal of heavy weapons, the deployment of Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) monitors, the demobilization of militias, the departure of foreign fighters, and eventual Ukrainian control of the international border, following elections. It called for a decentralization of power, a special status for Luhansk and Donetsk, the holding of local elections within the self-proclaimed republics, and general amnesty for fighters on both sides. Economically, the agreements focused on the resumption of commercial ties between the Kyiv-controlled and rebellious provinces. Finally, they enumerated provisions for humanitarian aid and the exchange of civilian and military prisoners. After a rebel victory at Debaltseve in 2015, the parties returned to the negotiating table to discuss elections and decentralization in detail. The German foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier then proposed that the regional elections be held under auspices of OSCE.

Soon after taking office, Zelensky took steps to implement this framework, agreeing to a prisoner-of-war exchange in early September 2019. He also embraced Steinmeier’s proposal to hold elections in October and was preparing to move Ukrainian forces back from the line of contact in the Donbas—a key Putin demand—in anticipation of a December summit in Paris. But that meeting would prove to be the zenith of Zelensky’s peace campaign, as he soon ran up against one of the forces that had also helped to stymie his anticorruption efforts: the nationalist far right.

Though Russia’s claims of a neo-Nazi government in Kyiv were never credible, there remains a dark undercurrent in Ukrainian politics. Far-right parties, some with a clear neo-Nazi bent, include the Congress of Ukrainian Nationalists, Svoboda, the Ukrainian National Union, the Right Sector, and the National Corps. Ultra-right-wing forces have not done well electorally in recent years, but they have nonetheless proven influential, in part because they are willing to resort to extra-parliamentary action. Radical nationalist groups have also been successful in making alliances with influential political players, including several powerful oligarchs. Few of these oligarchs endorse the far right’s ideology, but some seem to regard it as less threatening to their interests than the anticorruption agenda embraced by Ukrainian liberals. In addition, ultranationalists are overrepresented in the armed and security forces, including movements with their own militias such as S14, the Misanthropic Division, the Carpathian Sich (associated with Svoboda), Aidar, and Azov (associated with the National Corps). These battalions proved themselves to be effective early in the Donbas uprising, at a time when Ukraine’s army was in disarray. As the army rebuilt with substantial aid from the West, several of these paramilitary groups were incorporated into the regular forces.

In October 2019, after Zelensky had proposed a ceasefire and the withdrawal of forces from the line of contact, he went to the front to persuade the various battalions to honor it. A widely circulated video from the visit shows Zelensky debating the leader of the National Corps, Denys Yantar, who warned that there would be protests if the president agreed to a ceasefire. This was just one of many such warnings passed along by veterans’ groups. The Poroshenko ally Volodymyr Ariev warned that “if the president signs anything granting Russian influence in Ukraine, it would cause riots.”

These were not idle threats. The right never accepted the Minsk process, and met Zelensky’s tentative steps toward peace with stiff opposition. This began with smaller protests in Kyiv in October 2019. Then, on December 8, around ten thousand hard-liners rallied on the Maidan to encourage the president to say “no” to Putin. Rudenko notes that their “speeches in the center of Kyiv were, of course, a warning to Zelensky himself.” The website Myrotvorets, which makes an infamous list of allegedly anti-Ukrainian journalists and public figures, briefly included the president’s wife Olena Zelensky, claiming that she had inadvertently revealed sensitive information about the movements of Ukrainian armed forces on her Facebook page.

Such opposition would be daunting for any leader, but Zelensky promised that he was the man for the job. “I am not afraid to make difficult decisions,” he declared. “I am ready to lose my popularity, my ratings if needed, or even my post as long as we achieve peace.” Yet his enthusiasm for the Minsk agreements quickly wilted in the face of hard-line opposition. In a statement following the December 2019 summit, Zelensky echoed many of the right wing’s red lines when laying out Ukraine’s position. At that meeting, Zelensky had established a new formula for peace that included a limited special status for the Donbas (no different than any other Ukrainian region), and proposed only a piecemeal military disengagement. In July 2020, he signaled a lack of interest in the OSCE-coordinated Trilateral Contact Group—which had been a central platform for the negotiations—by appointing the former president Leonid Kravchuk, who was then eighty-six, as Ukraine’s representative. In early 2021, Zelensky moved substantial numbers of troops back toward the line of contact, closed pro-Russian media outlets, and charged the leaders of the breakaway republics with treason. Soon after these moves, Russia began building up its military forces on the other side of the border.

A charitable view of Zelensky’s failure to end corruption or peacefully settle the Donbas conflict might be that he had little room to maneuver in either case. Corruption is deeply ingrained in the structure of post-Soviet states, and the sort of negotiated peace needed to finish the civil war could have compromised the country’s sovereignty to an extent that would have been anathema to large numbers of Ukrainians, some of whom had guns and a propensity to use them. Addressing these issues would have posed political and perhaps even personal risks. But Zelensky did have opportunities—and, for a time, an overwhelming political mandate—to do so. That he folded so swiftly contradicts his well-managed image of integrity and courage; more importantly, his failures of foresight and fortitude meant that Ukraine squandered its chance to avoid the current conflict. Indeed, if Zelensky could have stood down his domestic opponents, particularly in the honeymoon period after his 2019 victory, perhaps he would not have had to stand up to the Russians in February 2022.

What explains Zelensky’s failure? To begin with, he and his team always favored style over substance. The Economist, which had expressed ardent support for Zelensky during the campaign, voiced concern just before his landslide victory, noting that he had “offered little indication of what exactly he plans to do, beyond vague assurances to maintain Ukraine’s Western course, improve the investment climate and end the war in the east.” Roman Bezsmertny, whom Zelensky appointed and then fired from the Ukrainian delegation to the Trilateral Contact Group, said that when he met with the president in the summer of 2019, he asked him how he viewed the situation in the Donbas: “He replied that by the new year, i.e., by 2020, we have to resolve the issue with the Donbas. And I already realized that he had no idea what it was. Because the words ‘solve the issue with the Donbas’ sounded like ‘tackle corruption,’ ‘engage in economic reform’—that is, do nothing.”

While Zelensky’s career in show business taught him to craft inspiring narratives, it provided him with little in the way of practical political experience. The former economics minister Tymofiy Mylovanov told the New York Times that Zelensky and his advisers “think differently” than typical politicians. “They think in terms of dramaturgy. They think, Who is the villain, who is the hero, what is the roller coaster of emotions?” Rudenko explains in his biography that “Servant of the People just stood for a popular TV series in which Zelensky, in the guise of Vasyl Holoborodko, skillfully defeated the government that hated the people.” But there was a yawning chasm between that simplistic drama and the real situation in Ukraine.

In a strikingly similar fashion to Churchill, Zelensky seems to be at his best during periods of chaos. Zelensky’s former press secretary Iuliia Mendel told the Financial Times that he was “a person of chaos. In war, it is chaos, he feels at home.” War, as the military theorist Carl von Clausewitz famously teaches, is a realm of disorder and uncertainty, and great wartime leaders are often those who thrive in such an environment. In his philosophical treatise On War, Clausewitz distinguishes between physical courage, which Zelensky may be said to have shown during the early days of the Russian invasion, and moral courage, or “courage before responsibility, whether it be before the judgement-seat of external authority, or of the inner power, the conscience.” Zelensky’s foreign supporters like to describe him as the conscience of the West, but there are many instances in which he has lacked moral courage in this sense.

This has been evident not only in his failure to stand up to extremist forces at home, but also in his dealings with Ukraine’s allies, as exemplified by his infamous phone call with Donald Trump in July 2019 when he was asked to investigate the Bidens. Zelensky’s efforts to ingratiate himself with Trump were bad enough, but perhaps can be explained by virtue of America’s importance to Ukraine and Trump’s transactional approach to politics. More troubling was Zelensky’s eagerness to denigrate others for little discernible reason. A transcript of the call records him carping about how the German chancellor Angela Merkel and the French president Emmanuel Macron were not doing enough for Ukraine, telling Trump that he was “absolutely right. Not only one hundred percent, but actually one thousand percent” when he said of European leaders that “all they do is talk.” He likewise echoed Trump’s view that the recently recalled American diplomat Marie Yovanovitch was “a bad ambassador.” As the French journalist Sylvie Kauffmann put it in the New York Times:

This popular maverick comedian turned real-life politician after playing one in a TV series, this promising reformer that President Emmanuel Macron of France had hosted at the Élysée even before he was elected, was in fact another spineless, unprepared leader jumping into President Trump’s every trap.The lack of moral courage Zelensky displayed during the exchange was not only personally embarrassing; it also boded poorly, as Kauffmann noted, for his ability to deal with the domestic problems he had been elected to confront.

While Russia is of course a major actor in Ukraine’s tragedy, the West, and the United States particularly, bears its own share of responsibility for Zelensky’s failures. America has done little since 2013 to advance a peaceful settlement of the conflict, and its most recent actions have only inflamed tensions. Under Barack Obama, the United States was guilty, in the judgment of the Brookings Institution scholar Alina Polyakova, of “absenteeism” in the Minsk process. Trump, meanwhile, seemed interested in Ukraine only so far as it could advance his own political fortunes. And soon after taking office, Joe Biden began undermining the Minsk agreements. Speaking in Washington on February 7, 2022, Biden’s secretary of state Antony Blinken grumbled about Minsk’s “sequencing,” a sign that the United States was unlikely to play a constructive role in the peace process.

Once the Russians launched their attack, of course, U.S. policy turned decisively against a negotiated settlement, even as the Zelensky government was talking with the Russians. In March 2022, Biden mused publicly about regime change, saying of Putin that “for God’s sake, this man cannot remain in power.” Putin complained in September of that year that peace talks with Ukraine had been going well until the West ordered Kyiv to “wreck all these agreements,” a charge that Western analysts and politicians have essentially confirmed. Though head of a NATO member country, the Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan complained that “the West has only made provocations and failed to make efforts to be a mediator in the Ukraine-Russia war,” which is likely why Turkey assumed a mediator role in 2022.

During the early days of the conflict, it briefly appeared that Russia and Ukraine were converging on a peace deal. In an interview with ABC News on March 7, 2022, Zelensky even said that he had “cooled down” on joining NATO. But later that month, he abruptly adopted a hard-line position, stepping back from compromise in the Donbas. At this point, any suggestion of territorial or diplomatic concessions to Russia were, in Zelensky’s increasingly Churchillian mindset, nothing more than a rerun of the 1938 French and British surrender in Munich (brokered by Churchill’s rival and predecessor Neville Chamberlain).

Meanwhile, Zelensky’s ambitions keep growing. Last December, he told the U.S. Congress, quoting FDR, that he intends to achieve an “absolute victory.” This victory would entail not only reclaiming territory seized by Russia since 2022, but also liberating the Donbas and Crimea. Following the dramatic Ukrainian counterattacks in the fall of 2022, which liberated large chunks of Russian-occupied territory, Zelensky’s star reached its zenith. This July, during the NATO summit in Vilnius, Zelensky struck a very different tone than he had sixteen months earlier, tweeting that it was “unprecedented and absurd” that Ukraine had not been provided with a time frame for joining NATO.

Zelensky and his advisers are now hoping to do more than make the Russian bear bleed for attacking Ukraine; they imagine they can rout Russia’s army and bring about Putin’s demise. Zelensky has increased his demands for sophisticated weaponry—including tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, and cluster munitions—and continues to insist on sanctions against Russia. He is also pushing to expand the geographical focus of the war. Ukrainian drone and artillery strikes on pre-2014 Russian territory have been increasing. Most alarmingly, in November 2022 the Ukrainian president doggedly maintained, with no evidence, that a missile that struck Polish territory and killed two Poles was a Russian attack rather than an accidental strike by a Ukrainian anti-aircraft battery. Had there been evidence for Zelensky’s claims against Russia, he might have triggered NATO’s Article 5 collective defense clause, widening and escalating the war.

Is Volodymyr Zelensky the right leader to settle this conflict? Here the comparison to Churchill may once again be apt, though not in a way that reflects well on Zelensky. Churchill’s Conservative Party was voted out of power in July 1945, two months after the end of fighting in Europe and before the surrender in the Pacific. Churchill seemed out of touch with British voters, who were disturbed by his distaste for social reform after six years of war. Zelensky has at times, like Churchill, become a hero outside of his country while his standing is diminishing at home. Where he once merely kowtowed to the far right during the Minsk process, he now seems to be embracing some of its leading figures, like the Azov commander Denys Prokopenko. And while it is not uncommon during wartime for democracies to restrict the press, the Zelensky Administration is doing so to such an extent that some claim journalism in the country has devolved into a “marathon of propaganda.” According to the Financial Times, Ukrainians are “already debating whether their leader, like his illustrious British predecessor, may be the right man for a war of national survival but the wrong one for the peace that follows.”

Reflecting on Poroshenko’s lack of enthusiasm for the Minsk framework, The Economist suggested that Zelensky’s predecessor came to see the Donbas conflict as a diversionary war, removing the pressure for domestic reforms. The nightmare scenario is that Zelensky will similarly recognize the frustration of his domestic agenda and find, like many other wartime leaders before him, that the only thing harder than conducting a war is governing in peace. Indeed, given the likelihood of a prolonged military stalemate between Ukraine and Russia—and the fact that, the longer the war drags on, the longer elections can be delayed under martial law—Zelensky may feel less pressure to consider diplomatic measures than he did in the early days of the conflict. Perhaps Zelensky’s biggest moral failure will prove to be prolonging a war that in a year or two won’t look any different on the ground, save for much larger cemeteries on both sides.