Composed of a mosaic of operational entities, the coalition of militant Islamist groups Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen seeks to hide behind an apparently united front the operations of its various constituents in the Sahel, so as to prevent any more robust response to its actions.

Health-tailings

- Although it is often considered a full-fledged operational entity, Jama’at Nusrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) actually includes several militant Islamist groups whose organizational structures, leaders, and goals differ.

- It is estimated that 75 per cent of the violent acts attributed to JNIM are the work of the Macina Liberation Front (FLM), active in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso.

- Groups that are part of the JNIM do not enjoy great popular support. They have increasingly exploited local criminal networks and, particularly with regard to the LWF, have carried out attacks against the civilian population.

Violent events related to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and western Niger) have increased almost sevenfold since 2017. With more than 1,000 violent events recorded in the previous year, the Sahel recorded the largest increase in violent extremist acts on the entire African continent for this period 1. The increase in attacks has been in the region, with a reported death of approximately 8,000, millions of internally displaced persons, large number of attacks on civil servants and traditional leaders, thousands of school closures and a significantly reduced economic activity.

The violent events attributed to the JNIM (Group of Support to Islam and Muslims or GSIM in French)), which have been seen from northern Mali to south-eastern Burkina Faso, account for more than 64% of all cases attributable to militant Islamist groups in the Sahel since 2017. The Macina Liberation Front (FLM) is by far the most active faction of JNIM; it operates from its fiefdom in central Mali, expanding into Burkina Faso territory.

JNIM functions as a professional organization in the service of its members. It gives the impression of being omnipresent and inexorably extending its hold. Viewing JNIM as a full-fledged entity, however, fuels the misperception of a unified command structure. This view ignores the local realities that have contributed to the activities of Islamist militants in the Sahel. To think that JNIM would be a unified organization that is the game of rebels whose motivations and activities, but also vulnerabilities, are obscured or concealed. The JNIM does not have a single HQ, has no operational hierarchy, and is not associated with any group of combatants that may be targeted directly by the army. So, knowing that nearly two-thirds of the acts of violence in the Sahel are attributable to this group, would not JNIM be a victim of a sham battle?

Who is the JNIM?

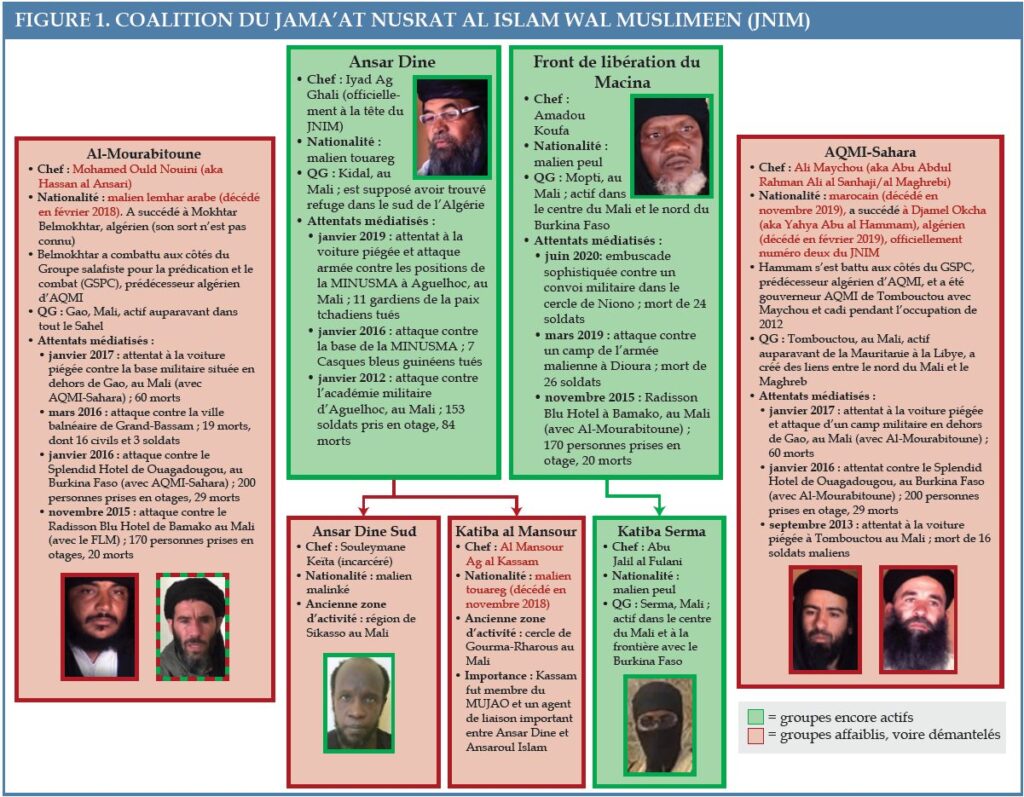

The JNIM coalition originally consisted of four militant Islamist groups affiliated with Al Qaeda: Ansar Dine, FLM, Al-Murabitoune and Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb in the Sahara (AQIM-Sahara). The composition of the groups is remarkable in that their respective leaders are from the Tuareg, Fulani and Arab jihadists from the Sahel and the Maghreb. The extent of ethnic and geographical representation created the illusion of a unified group with growing influence. In fact, the interests, territorial influence and motivations of each of these factions are very diverse from the outset2. JNIM is currently represented only by officials from two of the original groups, Iyad Ag Ghali of Ansar Dine and Amadou Koufa of the FLM, and to a lesser extent by Abou Jalil al Fulani, head of the Katiba Serma, an offshoot of the FLM.

Iyad Ag Ghali, the founder of Ansar Dine, is considered the leader or emir of JNIM. He created Ansar Dine in 2011, when the Mouvement Nationale de libération de l’Azawad (MNLA), a Tuareg separatist movement based in northern Mali, refused to name him at its head. Ag Ghali, an Ifoghas Kel Adagh Touareg, is from the Kidal region of northern Mali, where he participated in the Tuareg rebellions from the 1990s. As leader of Ansar Dine, he formed alliances with AQIM and the MNLA in 2012, proclaiming a “Islamist state” in May of that year as the “Islamist state.” In July 2012, Ansar Dine and AQMI-Sahara sided the Tuareg separatists to take control of Kidal and Timbuktu, respectively.

For most of 2012, militant Islamist groups occupied northern Mali before turning south, especially to the most populous regions of the centre. At the request of the Malian Government, a Franco-African military intervention (Operation Serval), launched in January 2013, made it possible to disperse terrorists to rural areas; the latter have taken refuge in the vast and rugged territory of northern Mali. Ag Ghali has since used Ansar Dine fighters to create an enclave of political influence in northern Mali and among its various armed groups.

Amadou Koufa first fought Ansar Dine in 2012 and 2013. After the dispersal of Ansar Dine following Operation Serval, Koufa began to preach extremism throughout central Mali. Born in Niafounké, Mali, and a member of the Fille community, Kufa is said to have become radicalized in contact with Pakistani preachers representing the Dawa sect in the 2000s3. To rally people to his cause, Koufa exploited the discontent of silly shepherds while at the same time calling for the establishment of an Islamist theocracy. In 2015, Koufa managed, with the help of members of his community, to rally many inhabitants of central Mali.

As leader of the FLM, Amadou Koufa orchestrated the most deadly rebellion of all those led by JNIM groups, including by attempting to overthrow existing traditional authorities and disseminate his conception of sharia law throughout central Mali. The LWF’s influence and activities have spread to northern Burkina Faso due to links with Ansaroul Islam, a militant Islamist militant group in Burkina Faso created by one of Koufa’s protégés, Ibrahim Dicko.

After Dicko’s death in 2017, groups of Islamist militant fighters operated to the border between Burkina Faso and Niger, building on existing criminal networks. Elders from Ansaroul Islam have rejoined the LWF, while from central Mali it extended its hold south towards the north and north-central Burkina Faso. Increasingly using violent tactics, LWF has made rapid progress in these more densely populated areas, seeking to recruit candidates locally or obtain sources of income.

According to experts, JNIM-affiliated groups earn between USD 18 and 35 million per year, mainly by resorting to extortion on the roads they control, on communities that depend on artisanal extraction, and to a lesser extent, by taking hostage-taking for ransom 44.

Photo credits (clockwise, starting from the photo at the top left): Iyad Ag Ghali, Amadou Koufa, Djamel Okcha, Ali Maychou (image from a video of JNIM on the SITE Intelligence Group), Abu Jalil al Fulani (Menastream), Souleymane Keita (photo by the police from the site A.CNN), Mohamed Ould Nouini (image from a JNIM video on the SITE Intelligence Group).

Although the JNIM has links with AQIM, the latter has never set itself a very important base of local support in the Sahel. Moreover, its regional influence, even in Algeria, where it first appeared, is experiencing a decline 55. The deaths of Al Qaeda-related leaders, including Abdullah Mekmalek Droukdel (AQIM), Djamel Okcha and Ali Maychou (AQIM-Sahara), and Mohamed Ould Nouini (Al-Murabitoune), have certainly accelerated the erosion of any direct influence claimed by the global al-Qaeda network on JN fighters. The ambiguity that hangs on the current status of AQIM-Sahara and Al-Mourabitoune highlights the major role played by JNIM. By offering a unified front, the JNIM coalition obscures the many setbacks suffered by each of these groups, thus offering the illusion of strong cohesion, command and control, and uncontestability.

This illusion has been reinforced by the almost doubling of violence and deaths that have occurred in the Sahel every year since 2016. But these acts are almost exclusively the work of the LWF. The FLM’s affiliation with the JNIM coalition masks its progress and limits the attention paid to it by international and regional forces.

Different objectives, tactics and territories

Although JNIM presents itself as a united front representing the jihadist Salafi ideology in the Sahel, there are four areas of intervention, according to the local dynamics, which form the basis of the actions of the groups constituting the JNIM.

Northern Mali. Since its inception, Ansar Dine has competed with other Tuareg separatist groups to assert himself as the main actor in northern Mali and southern Algeria. Ag Ghali has proved his political know-how in northern Mali by maintaining ties with lay leaders of the Tuareg community that he has used to ensure his own security and political influence. Although Ag Ghali and Ansar Dine may not be directly involved in drug trafficking or smuggling, it is certain that they are extorting members of international organized crime networks in northern Mali by taxing drug traffickers on the routes they use to transport their goods6.

The collaboration established in the past between Ag Ghali and the leaders of AQIM-Sahara and Al-Mourabitoune has enabled him to set foot in networks covering the Sahel and the Maghreb. Less integrated locally, AQMI-Sahara and Al-Mourabitoune have developed access to facilitate well-established smuggling operations in these areas, thus ensuring considerable income for their organizations. Following the deaths of AQMI-Sahara and Al-Mourabitoune chiefs, these operations were probably carried out by Ansar Dine, which helped to strengthen Ag Ghali’s influence in northern Mali.

Central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Amadou Koufa, of the FLM, and his supporters (including Katiba Serma) have promoted extremist ideology to fuel inter- and intra-Community tensions in Malian society. The Macina Liberation Front makes direct reference to the 19th-century Mildean Empireème, which covered approximately an area from central Mali to northern Burkina Faso. Although the Fulani are overrepresented among militant Islamist fighters in the Sahel, the FLM is not exclusively composed of members of this ethnic 77. Koufa’s views are also far from unanimous among the Fulani. However, the perception of LWF as a Peul group has given rise to ethnic stigmatization and reprisals, all of which are exploited by Kufa in order to recruit new members.

“More three-quarters of the violence committed by JNIM and associated deaths occurred in areas dominated by the LWF”.Kufa’s attacks on traditional leaders were undertaken under the guise of religious authority as an imam. The FLM imposed a strict version of sharia law to resolve disputes, introduced a new tax (zakat) and tightened social norms (especially for women) in several dozen villages in central Mali. In most of these areas, LWF fighters have effectively ousted the Malian authorities, which has allowed them to impose severe constraints on the inhabitants through the use of Islamist law. The LWF has applied a similar modus operandi in northern Burkina Faso.

In recent years, more than three-quarters of the violence committed by JNIM and associated deaths have occurred in areas dominated by the LWF. The latter has also targeted civilians, more than any other group in JNIM. Of eight violent events targeting civilians and attributed to JNIM, seven were perpetrated either in central Mali or in northern Burkina Faso. As LWF’s influence grew in these areas between 2018 and 2020, fighters rallied in Koufa targeted civilians in nearly one in three attacks.

The alliance of Kufa and Ag Ghali has advanced the individual ambitions of these two leaders and prevented both sides from entering into conflict through an effective delineation of their respective areas of influence and communities of interest. However, the goals and methods of the two groups remain different. While Ghali’s goals seem primarily political, Koufa’s goals are clearly aimed at violently spreading his interpretation of Islam and, consequently, social change. Indeed, FLM members carried out public executions of local imams and traditional leaders in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso who had dared to express a disagreement with the Koufa ideology, a phenomenon much less present in the enclave under the ferrule of Ansar Dine. In northern Mali, civilians were targeted in less than 2 per cent of events attributed to JNIM groups.

“The fighters rallied in Kufa targeted civilians in almost one in three attacks.”Eastern Burkina Faso and the border areas with Niger. As early as 2019, there has been an increase in violence committed by JNIM-related groups in eastern Burkina Faso, along the border with Niger, and then in the border areas with Benin and Togo. These attacks occurred outside the traditional LWF or Ansar Dine operating areas, making it impossible to say with certainty what the responsible groups are. These events, rather than being motivated by ideological or political considerations, seem to be more linked to the desire to control gold mining and trade routes. These activities represent a potentially lucrative source of income. It is estimated that the artisanal sites in these areas affected by Islamist militancy have the capacity to produce more than 725 kg of gold, or a value of 34 million dollars, per year8. The major nature reserves in that region also offer a refuge for militant Islamist groups that do not want to be spotted. Links with criminal groups guilty of smuggling and poaching in this border area have strengthened JNIM’s reputation to the point of view as an ever-increasing security threat.

South-western Burkina Faso. The sector of these three borders, located between Burkina Faso, Mali and Côte d’Ivoire, is affected by the smuggling and trafficking of small arms and light weapons that accompany goods transiting through Côte d’Ivoire for transport to major shopping centres in Mali and Burkina Faso. This area is also becoming important for gold mining. The series of attacks by the LWF from 2020 onwards and the prospects for gold mining have increased the risk of insecurity in the region 99. As is the case in eastern Burkina Faso, LWF combatants could seek to establish their presence in south-western Burkina Faso in order to appropriate some of the funds generated by these activities.

Strengths of the JNIM structure

The JNIM coalition structure gives it a number of advantages. In particular, they are due to the resulting ambiguity. The inability to decompose the JNIM to analyse its different entities, their objectives and functions within a broader coalition leads to misunderstandings about the power of the organization, its means and its local support. It ignores the potential vulnerabilities of the rebels concerned.

The fact of not being able to designate the entities responsible for the attacks, below the generic entity of JNIM, reduces the international and regional dimension of each group. At the same time, this ambiguity reduces the monitoring of each of the constituent groups of the organization, so that it becomes more difficult to specifically control the operations and methods of each of them. It is then difficult to provide a targeted response for each group making up the JNIM. By treating all incidents as coming from a single organization, the security forces were led to use a somewhat raw response that sometimes damaged relations between society and law enforcement, for the full benefit of JNIM groups.

The fact that JNIM is seen as a single actor operating throughout the region and brandishing as proof of the continued violence allows for envision of activity, support and influence that goes far beyond the current reality of JNIM. The majority of the acts committed by the JNIM are not claimed, so it is more difficult to attribute responsibility for the attacks to specific groups and therefore to respond appropriately. In fact, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, the violent acts perpetrated by JNIM largely reflect the areas of influence of its different constituent groups. This shows a great deal of consistency, and what is perceived as an expansion of the JNIM is actually that of its various groups.

Areas of historical influence of Ansar Dine, Ansaroul Islam, LWF and Katiba Serma

Note: Each point represents a violent event involving the group indicated between 2015 and 30 September 2020. Areas of influence shall be indicative and shall under no circumstances be considered as precise or static delimitations.

Source: Armed Conflict Location project – Event Data

The idea of a unified JNIM similarly conceals the diversity of its leaders and combatants. For example, after the deaths of leaders from Al-Murabitoune and AQIM-Sahara, no new leader could be identified. Similarly, the fate of ordinary combatants is not clear. Perhaps they have incorporated other militant Islamist groups in the region or have evaporated into local life. Given their close links with criminal enterprises in the Sahel, they may also have joined the transnational organized crime networks in northern Mali or the smuggling or gold-burn organizations of Burkina Faso. Therefore, even if Al-Mourabitoune and AQIM-Sahara are likely to be seriously damaged or even gone, ambiguity in the JNIM structure masks their failures and makes it more difficult to thwart their actions.

Weaknesses in the organizational structure of JNIM

Although Ghali and Kufa are the only leading figures in the coalition, no one knows what influence each of them has on the various JNIM groups. They are certainly not in a position to prevent rebel gangs from falling into crime or passing through competitors.

The LWF, for example, has experienced internal disagreements on how combatants can impose passland taxes and whether they can retain not only part of these taxes, but also what they could have acquired in combat as personal booty. Fighters often end up deserting, reorienting or flying on their own wings when they disagree with their leader, which contributes to fluid exchanges of fighters between militant Islamist groups and other armed groups in this vast region 11.

“The LWF has probably committed 78 per cent of attacks by militant Islamist groups on civilians.”The structure of JNIM probably masks the voltages between Ansar Dine and the FLM. The brutality with which the LWF has subjugated the local population in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso suggests that the view of an extremist Islam of Koufa prevails towards these communities. This could ultimately pit him against a more pragmatic Ag Ghali, who seems to be satisfied with the growing influence he enjoys in northern Mali, as demonstrated by the negotiations in 2020 aimed at handing over four foreign hostages against the release of some 200 prisoners. In his desire to expand the theatre of FLM operations, Koufa may well seek to distance himself from the less ideological contingents of JNIM. So far, the coalition-shaped structure has kept tensions, but there is a longer to looms between leaders and their lieutenants.

Infighting and inner quarrels between the various militant Islamist groups are not new to the Sahel and have helped to shape their activities in the past. Disputes over the territory and resources could have reignited tensions between the groups constituting the JNIM and the Islamist State in the Greater Sahara (EIGS), also active in the region, despite their common origins and their recent fighting together12. Reports of possible negotiations between Ag Ghali and the Malian government may have worsened relations with the EIGS. Further negotiations with the government could also isolate Ag Ghali from more radical jihadists in the ranks of JNIM 13.

To sustain themselves, the rebels must have some popular support. The increase in attacks on civilians, which accompanied the spread of the LWF from central Mali, suggests that such support is lacking. Since October 2018, the LWF has probably committed 78% of the attacks of militant Islamist groups on civilians attributed to the JNIM. The contrast is striking with other groups and areas of JNIM intervention, suggesting that popular resistance continues in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso 14.

Recommendations

The increase in violence by militant Islamist groups in the Sahel has alarmed communities and governments in the region. The JNIM-affiliated groups, mainly FLM and Ansar Dine, play a large role in the violence. Security actors must resist the image of a unified JNIM and undertake delicate analytical work to identify the various groups making up JNIM in order to better thwart their destabilization operations.

Stop considering JNIM as a unified operational entity. A multi-level approach is needed when dealing with a coalition of insurgents. It is important to identify and isolate the main task forces against which to act in order to undermine the JNIM coalition. It is mainly important to get to know FLM and Ansar Dine better. It will also be important to better identify the active elements in northern and eastern Burkina Faso. To this end, governments and intelligence services will need to better share the data they collect in order to develop better information and analysis, and to raise awareness of the locations and the way in which the entities that make up JNIM operate. Studying and targeting separate entities makes the enemy more tangible, but also highlights their differences and weaknesses. This method also makes it possible to demystify the JNIM and reveal the lack of local support for the different entities that make it up.

Strengthen counter-insurgency operations in central Mali and northern Burkina Faso. Tackling the LWF will require stronger counter-insurgency tactics. The aim will be to ensure the presence of security forces in key locations in order to put pressure on LWF fighters. Preventing them from moving freely between central Mali and northern Burkina Faso will hamper their ability to organize and launch attacks. Similarly, measures to combat the efforts to expand the LWF to south-western Burkina Faso will aim to retain the combatants in that area, in order to cut them off from the FLM base in central Mali. Given the relative novelty of this theatre of operation for the activities of the LWF, combatants in south-western Burkina Faso could not hold on their own for long. Thus, it would be particularly destabilizing to target these groups, as well as the movements and links between them in Kufa.

Targeting illegal networks with Ansar Dine. Ansar Dine and Ag Ghali are firmly rooted in the politics of northern Mali and its various separatist armed groups. In addition to counter-insurgency actions, it would be useful to enforce the law against the illegal networks supported by Ansar Dine in order to undermine Ghali’s operations. If the traffickers and local authorities joined Ansar Dine agree that this collaboration will certainly help them to be monitored and arrested, Ag Ghali will understand that he risks losing the political influence he is seeking to cultivate. Compromising Ag Ghali’s political belt, depriving him of its sources of funding and allies would help speed up the dismantling of Ansar Dine.

Protect the inhabitants of disputed communities. Counter-insurgency forces must realize that the vast majority of the local population rejects and fears militant Islamist groups affiliated with JNIM, including the FLM, and that these inhabitants want the support and help of the security forces. Government representatives and security forces must focus on establishing strong relations with the inhabitants of the areas affected by this scourge. This will need to be done, otherwise the relationship between the security forces and the inhabitants will be damaged. The indicator to be taken into account is not the number of militants killed, but the maintenance of the government presence with the citizens affected.

As such, it will be important to work with local officials and civil society to develop projects to protect the inhabitants, in order to counter violence against civilians and thus destroy the efforts to intimidate the LWF and its supporters against them. The local population will need to be given increased and long-lasting security guarantees in troubled areas, as well as it will be necessary to protect local leaders, as they are more likely to be targeted by militant Islamist groups as they appear to be collaborating with the government. The voices of non-violent city leaders who resist intimidation of militant Islamist groups must be amplified and protected.

In other cases, it will be necessary to reassure the inhabitants, who, after being forced to work for militant Islamist groups, will not be subjected to the brutal repression of the security forces. The local population working in artisanal mines, or near well-known smuggling routes, could be suspicious in the event of an increased presence of the security forces. Therefore, it is the responsibility of local and national governments to develop programmes and policies that help to support the economies of these populations. Working closely with local officials to better regulate artisanal mining and transport will restore security among ordinary citizens. This security, in turn, will change the economic opportunities of these populations. This approach will also have the advantage of preventing militant Islamist groups from grabbing income from illicit activities that seriously harm local economies.

Continue to seek policy solutions. Ag Ghali and Koufa are said to have begun negotiations with the Malian government and sometimes with the local authorities, in order to consider a truce. Their demands are often inconceivable, such as the complete withdrawal of French troops from the region or the adoption by the public authorities of an extreme interpretation of the Shariah. However, there is a need for further dialogue to explore political solutions for conflict resolution.

The negotiations also mean that the various leaders take a position on key issues. This is important for understanding the leaders’ goals, but also to raise public awareness of the issues at stake in the conflict. Dialogue can also reveal key differences between the various factions of militant Islamist groups. Disparities between the objectives of Ghali and Kufa, particularly with regard to the interpretation and implementation of the sharia, could also weaken the cohesion of their coalition. The willingness of Ghali and Kufa to reach solutions, together with the national authorities, could also create divisions among combatants between those seeking a political agreement and those for more radical solutions in their ranks.

Establish reintegration policies for simple combatants. Local and national governments can benefit from infighting and the constant rotation of military leaders by providing combatants with exits from militant Islamist groups. The level of engagement of simple combatants varies. By engaging with lower- and middle-level military leaders, local and national administrations will be able to better understand the motivations of these fighters, highlight the possibilities of disarmament and thus undermine the survival of the LWF and Ansar Dine.

Reintegration policies should be targeted as a matter of priority by these simple combatants. Policies to encourage defections should be strengthened, while sending these combatants the message that local governments and officials have other options to offer them. Experiences from other reintegration contexts have shown the importance of working hand in hand with the inhabitants to facilitate this transition, otherwise the fighters end up joining the jihadist networks. These fighters are supposed to know each other, and the motivations of Ghali or Kufa might not matter to them as much as their personal relationships or opportunities. Amnesty and reintegration programmes played a significant role in the weakening of the Salafist Group for preaching and fighting in Algeria, and similar policies weakened Islamist rebellions elsewhere. If governments can guarantee security and offer prospects other than being a mere performer, combatants may end up admitting that it is better to make arms, including in the Sahel.

Notes

⇑All data on violent events and deaths attributed to JNIM groups are from the database of the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project.

⇑- Alex Thurston, Jihadists of North Africa and the Sahel: Local Politics and Rebel Groups (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020).

⇑Pauline Le Roux, “Centre du Mali facing the terrorist threat”, ,Illumination, Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, 25 February 2019.

- Christian Nellemann, R. Henriksen, Riccardo Pravettoni, D. Stewart, M. Kotsovou, M.A.J. Schlingemann, Mark Shaw and ed. Tuesday Reitano, “World Atlas of Illicit Flows: A RHIPTO-INTERPOL-GI Assessment” (Oslo: RHIPTO Norwegian Center for Global Analyses, 2018), 8.

⇑Geoff D. Porter, “AQIM Pleads for Relevance in Algeria”, CTC Sentinel 12, No. 3 (West Point: Combating Terrorism Center, 2019).

⇑Peter Tinti, “Drug Trafficking in Northern Mali: A Tenuous Criminal Equilibrium”, ENACT Analysis Report No. 14, September 2020.

⇑Modibo Ghaly Cissé, “Understanding the Sparkful Perspectives on the Crisis in the Sahel”, Illumination, Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, 24 April 2020.

⇑David Lewis and Ryan McNeil, “How Jihadists Struck Gold in Africa’s Sahel”, Reuters, 22 November 2019.

⇑Roberto Sollazzo and Matthias Nowak, “Tri-Border Transit: Trafficking and Smuggling in the Burkina Faso-Côte d’Ivoire-Mali Region”, Security Assessment in North Africa, Small Arms Survey, October 2020.

⇑Héni Nsaibia and Caleb Weiss, “The End of the Sahelian Anomaly: How the Global Conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qaida Finally Came to West Africa”, CTC Sentinel 13, No. 7 (West Point: Combating Terrorism Center, 2020), 11.

⇑Andrew Lebovich, “Mapping Armed Groups in Mali and in the Sahel”, European Council on International Relations (2019).

⇑Pauline Le Roux, “How the Islamist State in the Greater Sahara exploits the borders of the Sahel”, Éclairage, Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, 21 June 2019.

⇑Alex Thurston, “Political Settlements with Jihadists in Algeria and the Sahel”, West African Papers No. 18 (Paris: OECD, 2018).

⇑Anouar Bukhars, “The Logic of Violence in Africa’s Extremist Insurgencies”, Perspectives on Terrorism 14, No. 5 (2020).

⇑Pauline Le Roux, “Responding to the rise of violent extremism in the Sahel”, African Security Bulletin No. 36 (Washington, D.C.: Centre for Strategic Studies of Africa, 2019).

⇑Fransje Molenaar, Jonathan Tossell, Anna Schmauder, Rahmane Idrissa, and Rida Lyammouri, “The Defied Status of the Customs: The Legitimacy of Traditional Authorities in the Limited State Areas of Mali, Niger and Libya”, CRU report (The Hague: Clingenda Netherlandsel Institute of International Relations, 2019).