Abstract: Following a sustained buildup in attacks throughout 2019 and into first half of 2020, the Islamic State’s insurgency in Iraq underwent a steep decline over the last 20 months. A comprehensive analysis of attack metrics shows an insurgency that has deteriorated in both the quality of its operations and overall volume of attack activity, which has fallen to its lowest point since 2003. The Islamic State is increasingly isolated from the population, confined to remote rural backwaters controlled by Iraq’s less effective armed forces and militias, and lacks reach into urban centers. The downtrend in Iraq is likely attributable to stepped-up security operations, pressure on mid- and upper-tier leadership cadres, and the Islamic State’s refocusing on Syria—graphically illustrated by the January 20, 2022, attempted mass breakout by the Islamic State at Syria’s Ghweran prison. The key analytical quandary that emerges from this picture is whether the downtrend marks the onset of an enduring decline for the group, or if the Islamic State is merely lying low while laying the groundwork for its survival as a generational insurgency.

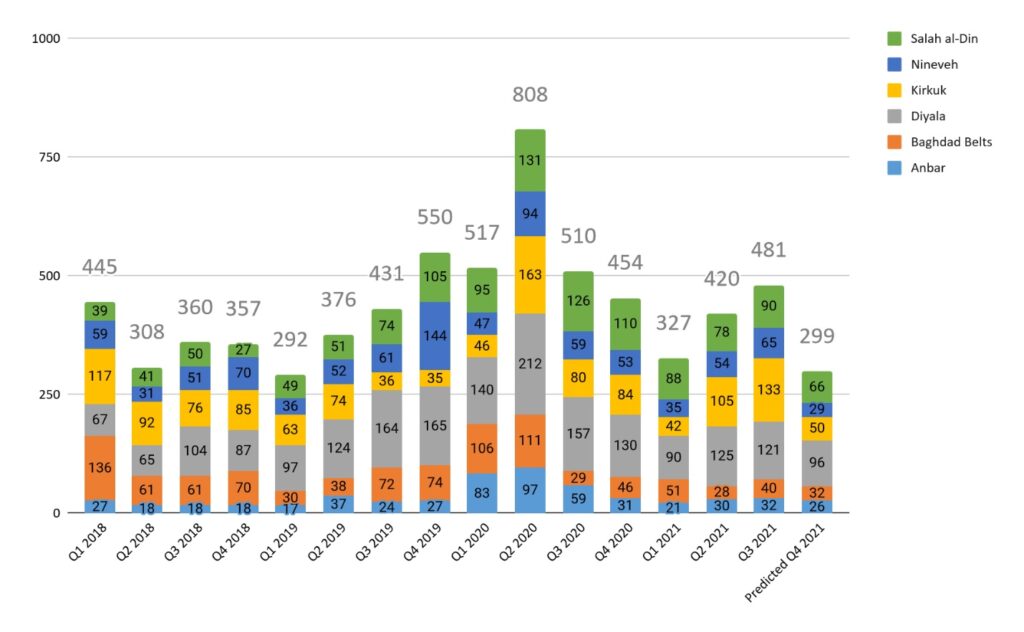

Incidents like the January 20, 2022, Islamic State prison break1 at Ghweran, Syria, or the January 21, 2022, massacre of 11 Iraqi Army soldiers in Diyala, Iraq,2 give the sense of another Islamic State resurgence,a but a longer and more methodical survey of attack metrics shows that the Islamic State’s insurgency in Iraq is looking increasingly anemic, in contrast to the sustained resurgence it enjoyed over the course of 2019 and early 2020. Attack activities plummeted across the board in mid-2020, falling from a high of 808 Islamic State-initiatedb attacks in Q2 2020 to 510 during the third quarter of that year. Attack trends persisted in an erratic pattern of ups and downs for the remainder of the period surveyed in this study, averaging 330 per quarter over the remaining 17 months from July 2020 to November 2021. These national-level figures, supported in this article by an exhaustive qualitative and province-by-province breakdown, paint a picture of an insurgency that feels increasingly isolated and disconnected from the broader Sunni Arab population. Under pressure from rolling security offensives, the expansion of the government security footprint further into rural areas, and an energetic campaign of leadership decapitation strikes, the Islamic State is struggling to maintain even historically low levels of attack activity. While all these factors have certainly contributed to driving down attack activity in Iraq, in the authors’ view, they lack the explanatory power to fully account for the ebbing of the insurgent tide over the last 20 months. The key analytical quandary for insurgency watchers that emerges from this study is how much of the Islamic State’s present weakness can be attributed to these variables, or if some other, unseen factor, such as the deliberate preservation of forces by the Islamic State, is driving the trajectory of the insurgency.

This article extends the metrics-based analysis used in three prior CTC Sentinel pieces3 in 2017, 2018, and 2020, adding a further 20 months of Islamic State attack metrics in Iraq, picking up from the start of April 2020 (where the last analysis ended) to the end of November 2021. As in the prior study, this article looks at Islamic State attacks in Anbar, Salah al-Din, Baghdad’s rural “belts,”c Nineveh, Kirkuk, and Diyala. The authors also look at the Islamic State’s provinces in Syria, making some rudimentary comparisons between activity levels in Iraq and the areas of Syria directly adjacent to the Iraqi theater of operations.d

As with previous studies, to maximize comparability, this analysis used exactly the same data collection and collation methodology as the December 2018 and May 2020 CTC Sentinel studies. Attacks were again broken down into explosive or non-explosive events,e and also by the four categories of high-quality attacks (effective roadside bombings,f attempts to overrun Iraqi security force checkpoints or outposts,g person-specific targeted attacks,h and attempted mass-casualty attacksi). As with any set of attack metrics, this analysis represents a partial sample that undoubtedly favors more visible attack types (explosions, major attacks) over more subtle enemy-initiated actions (such as kidnap or intimidation). Nevertheless, as with the previous studies, the immersive, manual coding of thousands of geospatially mapped attacks remains one of the best ways to gain and maintain a fingertip-feel for an insurgency.

The piece will unfold in a recognizable format borrowing from previous studies. First, the authors will review national attacks trends and high-quality attack trends. Then, the piece will proceed with quantitative and qualitative attack trends at the provincial level. Next, the article addresses the question of centralized direction and resourcing. In the period examined in this article, there have been two attack campaigns by the Islamic State that suggest surviving centralized direction and resourcing: first, efforts to carry out “external attacks” into the well-secured Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), and second, an integrated assault on Iraq’s electricity sector in the summer of 2021. Both will be examined in turn. The article will conclude with an analytical section on the potential causal factors of the Islamic State decline (including conditions in Syria) and then discusses the predictive outlook for the future of the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq.

National Trajectory of Islamic State Attacks

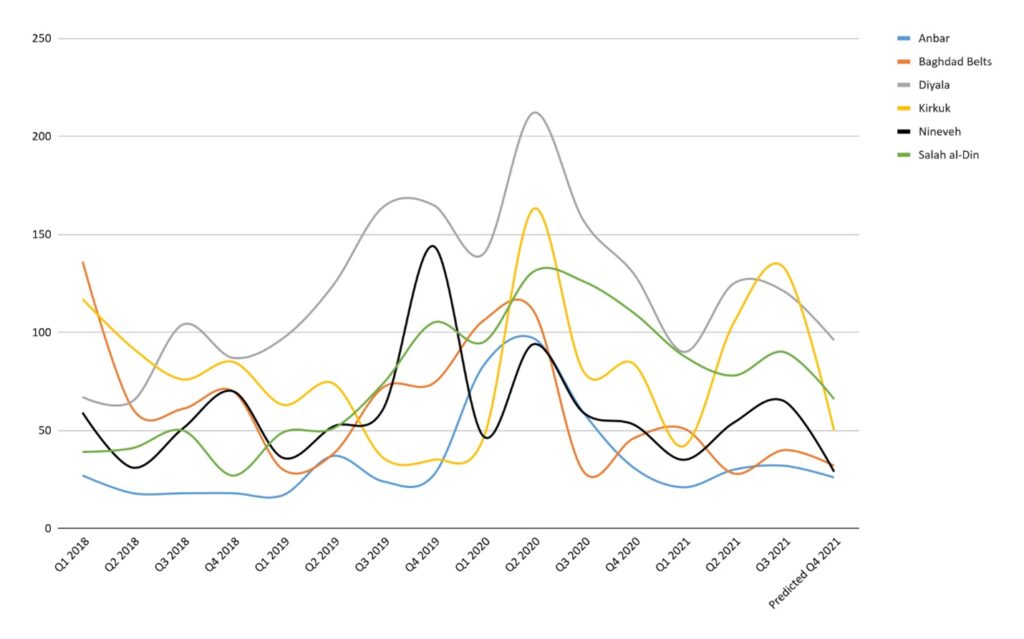

The December 2018 CTC Sentinel study of Islamic State attack patterns in Iraq chronicled a stark decline in Islamic State attack metrics in late 2017 and the first half of 2018,4 while the May 2020 CTC Sentinel metrics study described a strong partial recovery of Islamic State attacks in Iraq in the second half of 2019 and the first quarter of 2020.5 In this new study, as shown in Figure 1, the authors discovered that the partial recovery of Islamic State capabilities in Iraq appears to have peaked in Q2 2020 and has since experienced a slow reversal in quantitative terms.

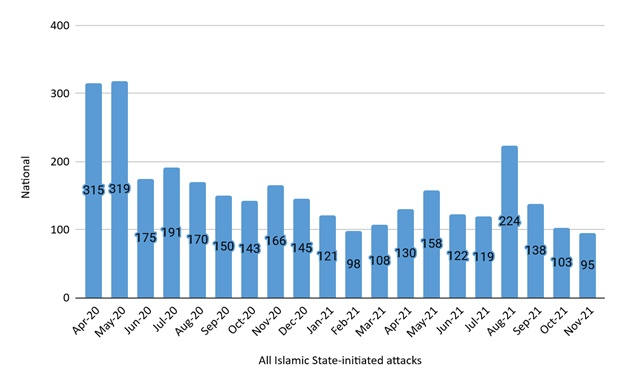

As the May 2020 analysis predicted (based on metrics up to March 31, 2020), Islamic State attacks continued to increase for some months in Q2 2020, reaching a level similar to 2012 intensityj (including 315 Islamic State attacks in April 2020 and 319 in May 2020,6 a period roughly correlating with Ramadan in 2020k). Yet this upward trajectory was not sustained. Instead, the number of Islamic State attacks dropped off sharply in June 2020 and throughout the third quarter of 2020, settling back at a level more commonly seen in 2019.7 Though undulating above and below the trendline in specific months, the quarterly attack metrics trended downward in 2021. This gradual decline trend is clearer when viewed via the monthly Islamic State attack metrics shown below (Figure 2).

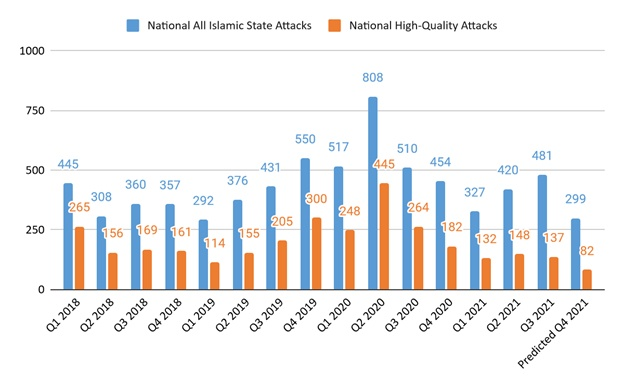

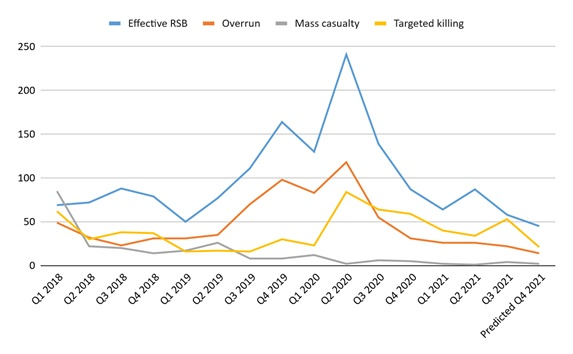

Another very clear trend is a steady and unmistakable decline in the quality of Islamic State attacks in Iraq in late 2020 and 2021. Figure 3 shows the raw numbers of high-quality attacks (effective roadside bombings, attempts to overrun Iraqi security force checkpoints or outposts, person-specific targeted attacks, and attempted mass-casualty attacks). Again, the second quarter of 2020 marked a high point for high-quality attacks within the new study period, but this level of performance was not sustained. As Figure 4 shows, the proportion of high-quality attacks declined, from an average of 61.6% of attacks in Q2 2020 to an average of 41.6% in Q3 2021.8 All categories of high-quality attacks also declined, as shown in Figure 5, but two weathered 2020-2021 better than the others. Effective roadside bombing held up relatively well as a tactic, and the targeted killing of specific security and local officials overtook attempted overruns of positions as the second most common high-quality tactic from Q3 2020 onward.9 In the authors’ experience of analyzing Iraqi security dynamics,l this speaks to the Islamic State’s declining capability to win stand-up fights against Iraq security force (ISF) units, with fewer overrun efforts being undertaken and a lower proportion being effective enough to be coded as recognizable overruns. As this study will discuss at various points, the gradual hardening of ISF outposts may have helped in this process, with thermal camera mastsm giving outposts better situational awareness of Islamic State raids mustering to attempt overrun attacks.n Table 1 in the appendix provides the quarterly national metrics for Islamic State-initiated attacks in Iraq since the beginning of 2018, including across the different categories of high-quality attacks.

Quantitative and Qualitative Attack Trends at the Provincial Level

In terms of provincial-level comparisons (see Figure 6), Diyala produced the highest number of Islamic State attacks in all but four months of the new 20-month dataset,o confirming its longstanding position as the most consistently active operating environment in Iraq for the Islamic State.10 One stand-out observation from the new attack data is the growing role of Salah al-Din as a cockpit of Islamic State attack activities in Iraq, with the province moving from being a relative backwater to the second or third most active attack location in any given quarter of 2020 and 2021.p By contrast, early 2020 Islamic State attack hotspots such as Anbar and the rural Baghdad belts fizzled out in the latter half of 2020 and Kirkuk struggled to maintain a consistently high level of attack activities.11 To dig more deeply into provincial dynamics and trends, the following sections will proceed governorate-by-governorate across the six provinces.

Anbar

In the authors’ May 2020 CTC Sentinel metrics analysis, Anbar was showing signs of recovering as a major Islamic State attack location after years in the doldrums. In the first quarter of 2020, there were three times the number of attacks each month (27.6) than the 2019 average (8.7).12 This continued in the second quarter of 2020, with a monthly average of 32.3 attacks in Anbar.13 But the Islamic State then suffered a precipitous drop-off of all forms of attack in Anbar from June 2020 through to late 2021. While the monthly attack average was 22.5 in 202014 due to the high levels of Islamic State activity early in the year, the monthly attack average for the first 11 months of 2021was just 9.0,15 essentially a return to the very low attack levels of 2019.16

High-quality attacks in Anbar also dropped sharply after the summer of 2020. In Q2 2020, the Islamic State in Anbar was still striking out regularly from rural redoubts in the Wadi Husseinat, on the high plateau east of Rutbah.17 Effective overruns were targeting border guard stations on the Syrian, Jordanian, and Saudi borders, as well as outposts on the highways ringing the central desert plateau.18 Islamic State cells were moving back down onto the International Highway between Amman and Baghdad to abduct truckers and security forces at fake military checkpoints.19 Notably, the Islamic State was beginning to construct car bombs and motorcycle bombs in this redoubt for use in intimidation attacks on Sunni cities like Rutbah, Ramadi, and Fallujah.20 Effective roadside bombs were being used an average of 10.6 times a month in Q2 2020, including vehicle-carried devices detonated at highway bridges as a form of vehicle-emplaced roadside bomb.21

Fast forward to the second half of 2021 and the picture changed considerably. There were 32 Islamic State attacks overall in Q3 2021, versus 97 in Q2 2020.22 Vehicle bombings and other attempted mass-casualty attacks were down to zero in the second half of 2021.23 q Effective roadside bombings dropped to 2.2 per month in the second half of 2021 versus 10.6 per month in the second quarter of 2020.24 With the exception of some Islamic State raiding around Nukhayb,25 r overrun attacks in Anbar largely ceased, with just 1.6 overrun attacks per month in July-November 2021 versus an average of 6.6 per month in Q2 2020.26 In general, Anbar Islamic State cells have migrated toward the softest of soft targets: dropping electricity pylons and abducting and ransoming shepherds.s

Baghdad Belts

Like Anbar, the Baghdad belts (areas constituting heavily irrigated farmlands in rural districts bordering Baghdad but not within the city limits) were recovering as an Islamic State attack location in early 2020, with an average of 37 attacks per month in Q2 2020,27 high for the post 2014 insurgency around Baghdad but lower than even the quietest moments in Iraq’s 2003-2011 insurgency.t Yet even this level of activity dropped off sharply in July 2020 and has not yet recovered at the time of writing. By the third quarter of 2021, the monthly average in the Baghdad belts dropped to 13.3 attacks.28 Of note (see Figure 7), high-quality attacks in the Baghdad belts dropped by an exact order of magnitude, from 23 per month in Q2 2020 to 2.3 per month by Q3 2021.29 The roadside bombing cells active in western Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib in the latter half of 2019 disappeared completely, with effective roadside bombings in the Baghdad belts dropping from a monthly average of 13.3 in Q2 2020 to a measly 0.6 in Q3 2021.30 u Overruns of rural checkpoints in the Baghdad belts dropped from an average of five per month in Q2 2020 to 0.3 per month in Q3 2021.31 Precision killings also dropped from an average of five per month in Q2 2020 to 1.6 per month in Q3 2021.32

As was the case in the authors’ May 2020 CTC Sentinel metrics analysis,33 the northern Baghdad belts remained the principal locus of Islamic State attack activity in the Baghdad belts in the new data coverage period, accounting for 49.2% of all attacks in the Baghdad belts and 60.3% of all high-quality attacks in those areas.34 Areas such as Tarmiyah, Mushahidah, Taji, and Soba Saab al-Bour continued to be tough operating environments in Baghdad for ISF units and tribal militias throughout the period on which this study focuses.35 v Tarmiyah is historically viewed by the Iraqi intelligence community36 as the major “switch-point” between the Islamic State operating areas west of the Tigris (Anbar, the Euphrates River Valley, plus desert zones around Lake Tharthar) and those to the east (radiating northeast up the Tigris, Udhaim, and Diyala River Valleys, and the Kurdish border). As one Iraqi intelligence operator noted: “Tarmiyah was the first wilayat of Al-Qaeda in Iraq and all the walis of Baghdad have sheltered there.”37 Yet, as the next section on Salah al-Din will note, the Islamic State may have found Tarmiyah too hot to handle in the face of sustained ISFw and coalition pressure,x prompting an apparent relocation of the redoubt further north to Yethrib.

As in other provinces, the Baghdad belts saw a steep decline in the quality of Islamic State attacks during the new data period. In Q2 2020, the Islamic State still carried out numerous effective ambushes and roadside bombings,38 y and successfully attacked Iraqi Army battalion and brigade headquarters.z Yet Islamic State high-quality attack activity in the northern Baghdad belt dropped off sharply from August 2020, and then again (almost to nothing) from April-May 2021 onward.39 Aside from sporadic targeted killings and half-yearly efforts to send a suicide bomber into Baghdad,40 the northern belts grew extraordinarily quiet in 2021, and almost devoid of high-quality attacks.41 aa

Salah al-Din

The authors’ May 2020 CTC Sentinel metrics analysis characterized Salah al-Din as a formerly sleepy Islamic State operating location that was waking up and becoming highly active in early 2020,42 ranking as the third most active Islamic State attack location (after Diyala and Kirkuk).ab In Q2 2020, Salah al-Din suffered an average of 44 Islamic State attacks per month, including an average of 26 high-quality attacks (59.0% of all attacks, comparable to the national average of 61.1%).43 Compared to other provinces, Salah al-Din saw a more sustained and even pattern of attacks in late 2020 and 2021 that only gently declined over a longer period. For instance, between April 2020 and November 2021 attacks halved in Diyala, reduced to one-third of their April 2020 levels in Baghdad and one-quarter in Nineveh, to one-seventh in Kirkuk and one-eighth in Anbar. In contrast, in Salah al-Din, Islamic State attacks were still more than half their April 2020 levels (40 attacks) by November 2021 (24 attacks).44

Admittedly, Islamic State attacks in Salah al-Din became much lower quality in late 2020 and 2021, with a 39.4% decline in all attacks from Q2 2020 to Q3 2021, but a whopping 71.8% decline in high-quality attacks during the same period.45 The type of high-quality attack that held up the most between Q2 2020 and Q3 2021 in Salah al-Din was targeted killings: Whereas roadside bombs dropped by 64.9% over this period and overruns by 85.8%, targeted killings continued at almost unchanged levels from Q2 2020 to Q2 2021 (4.6 attacks per month in Q2 2020 and four attacks per month in Q2 2021).46 A high proportion of the Islamic State’s remaining effective attacks in Salah al-Din was actually some variation of active defense measures,47 such as raiding, mortaring, and sniping at the security forces surrounding Islamic State redoubts like the Jallam Desert, the Zarga area south of Tuz Khurmatu, the Makhul range, and the desert west of Bayji.48 Overall, in the authors’ assessment, the Islamic State tried very hard to prevent security forces from making greater inroads into Islamic State rural redoubts in Salah al-Din.49

The only notable offensive campaign launched by the Islamic State in Salah al-Din in the period examined in this article seems to have been a determined effort to build a new defensive bastion in Yethrib, a densely irrigated farming community in southern Salah al-Din that fills the eight-mile space between Balad city and Balad airbase. Only 40 miles north of Baghdad, Yethrib may have been developed by the Islamic State from June 2020 onward50 ac as an alternative to Tarmiyah as the “switch” point between the Syria-Euphrates line of Islamic State guesthouses and the lines branching off east of the Tigris to Jallam, Diyala, Hamrin, and Kirkuk. There certainly does appear to be a correlation between the July 2020 drop-off of Islamic State activityad in Tarmiyah and the ramping up of Islamic State activities in Yethrib, just 20 miles north of Tarmiyah and directly accessible via farming areas between the Tigris and the main north-south road corridor, Highway 1. Throughout 2020 and 2021, the Islamic State accelerated the targeted killings of Yethrib tribal, government, and security force leaders,51 a familiar pattern (in the authors’ experience) in areas where they seek to overawe the local populous and establish “no-go” zones for the security forces and farmers.52 The worsening situation in Yethrib gained national and international notice when the Islamic State undertook a massacre of tribal militia and police troops at a funeral in Yethrib on July 30, 2021, killing at least eight persons and wounding at least 19.53 If the authors’ identification of a new Islamic State base zone at Yethrib is accurate, it would be an indication that the movement can still undertake a kind of operational-level redeployment in order to avoid intensive targeting by government forces (such as the ISF surge at Tarmiyah in early 2020).54

Nineveh

In their May 2020 CTC Sentinel metrics analysis, the authors took note of what seemed to be an increasingly strong and well-entrenched insurgency taking root in Nineveh.55 Overall attack activity rose continuously through 2019, before surging to an average of 34.1 attacks per month in the six month-period including Q4 2019 and Q1 2020.56 And yet during the following months, Nineveh showed a clear downtrend in insurgent activity, with attacks falling steadily from an average of 31.3 per month in Q2 2020 to 19.7 during Q3 2021.57 Islamic State attacks then recovered somewhat for around a year, then fell into another less pronounced decline to an average 16.7 attacks per month after June 2021.58 Effective roadside bombing activity in the Tigris River Valley (TRV)ae—the main driver of quality attacks in the province—all but shut down during the latter half of 2021, averaging just 2.5 attacks per month.59

High-quality attacks in Nineveh saw an even steeper decline, from an average of 20.6 during the busy second quarter of 2020 to 4.6 in Q3 2021.60 The decline in high-quality activity noted across Iraq during the period covered in this study was particularly stark in Nineveh. In the first half of 2020, the rural TRV south of Mosul was experiencing an energetic insurgent roadside bomb campaign. IED cells based out of historic insurgent staging grounds in Hammam al-Alil, Ash Shura, and the Jurn corridor generated an average of 15 effective roadside bombings per month in the first six months of 2020,61 mostly targeting tribal militia and police vehicles on local road systems.62 Local emergency police and tribal militia checkpoints were routinely targeted with drive-by gunfire attacks and rural Sunni Arab communities were subjected to persistent insurgent intimidation via roadside bomb strikes on produce trucks, irrigation pumps, and farming equipment.63 ISF and Shi`a Popular Mobilization Force (PMF) clearance operations into insurgent fallback zones in the deserts west of Highway 1 were aggressively contested by the Islamic State with effective, high-casualty roadside bombings and ambushes.64

During the latter half of 2021, attack activity in Nineveh was almost entirely sustained by two dramatic spikes in the demolition of electricity transmission lines in July and August 2021.af One of the more intriguing aspects of the insurgency in Nineveh was the possible reactivation of local bombing cells to join in the Islamic State’s national campaign of pylon attacks.ag The uptick in pylon strikes in Nineveh in Q3 2021 was particularly noticeable in otherwise dormant operating areas such as Mosul’s western rural “belts,”ah an area that was the focus of an intensive Islamic State mukhtar (tribal chiefs and village elders) killing effort in 2018 and 2019.65 In the authors’ assessment, this hints at a latent kinetic attack capability that was briefly switched on and off, presumably with some degree of centralized direction.

By the end of 2021, attack activity in Nineveh had largely tapered off, with the province apparently relegated by the Islamic State to the role of a transit corridor and temporary staging hub. The apparent deactivation of Nineveh as an insurgent attack area after Q2 2021 was accompanied by a noticeable increase in reports of transit by Islamic State cells through the province toward active attack locations like Salah al-Din and Kirkuk.ai Based on reports of successful arrests of would-be infiltrators, it is likely that a stream of Islamic State members and their families entered Iraq from Syria during the latter half of 2021.aj The majority of these Islamic State returnees crossed into Iraq along the border between Nineveh and northeastern Syria’s Hasakah province, before moving down the Islamic State ‘rat line’ of guesthouses in the TRV and Wadi Tharthar to the Lake Tharthar area and the Euphrates River Valley north of Baghdad.66 During their transit through Nineveh, these Islamic State groups passed through former Islamic State rural redoubts around Tal Afar, Ayadhiyah, and the Jurn corridor67—all areas where security operations continue to turn up large stocks of cached weapons, explosives, and other materials, but where the Islamic State has apparently made no significant effort to recommence attacks.68 ak This may be another indicator that northern Nineveh is an area of latent insurgent potential for the Islamic State, if and when the movement decides to reactivate its attack activities there.

Kirkuk

Kirkuk province was another powerhouse of the early 2020 insurgency69 that struggled in late 2020 and during 2021 to sustain its elevated status. In Q2 2020, attacks in Kirkuk spiked to 54.3 per month, driven by a remarkably strong surge in attacks during April and May (i.e., Ramadan) following a slow start to the year over the first quarter of 2020.70 From Q3 2020 to Q1 2021, Kirkuk saw a steady decline in activity, dropping to a record-low monthly average of 14.0 attacks in Q1 2021.71 Attack activity in Kirkuk then bounced back up to an average of 39.6 average monthly attacks during Q2 2021 and 44.3 in Q3 2021, followed by a notably weak final quarter (including a prorated December based on the average of October and November metrics), with the monthly average dropping to 16.3 attacks.72 al

High-quality attacks in Kirkuk declined, falling sharply from an average of 32 high-quality attacks per month during Q2 2020 to a low of 6.6 in the first quarter of 2021.am Though high-quality attacks did slightly increase again (to an average of 12.6 per month in Q3 2021),73 effective attacks represented a significantly diminished percentage of all Islamic State-initiated activity (30% of all Q3 2021 attacks, versus 58.8% of Q2 2020 attacks).74 Effective roadside bombings and successful outpost overruns saw the most dramatic drop-offs in Kirkuk, falling from an average of 15.7 and 13 attacks per month in Q2 2020 to 4.9 and 2.7 averaged across the Q3 2020 to Q3 2021 period, respectively.75 Targeted killings held up slightly better, declining from an average of six per month in Q2 2020 to 3.4 over the subsequent 17 months.76 In the authors’ assessment, this pattern of striking softer targets usually occurs in areas across Iraq where the Islamic State is less confident that it can tactically overmatch ISF units.an

A detailed review of attack activities, ISF clearance operations,77 and coalition surveillance patterns78 suggests that the Islamic State has struggled to expand its geographic footprint in Kirkuk since the May 2020 CTC Sentinel study. Despite a consistent pattern of “mukhtar slayings”ao plus other targeted killings and lower-visibility intimidation of local communities, the Islamic State has been unable to expandap from its sanctuaries along southern and western edges of Kirkuk province into the more densely populated Jabbouri tribal confederationaq farming areas of Hawijah, the Mahuz triangle, and the Riyadh corridor, all historic strongholds for insurgent groups like Jaysh Rijal al-Tariq al-Naqshabandi (JRTN) and Ansar al-Sunna.79 As in May 2020, Islamic State activity is restricted to the thinly populated Obeidi tribal confederation areasar of Rashad and Daquq districts, where hardscrabble, semi-abandoned farming villages are interspersed with impassable, densely vegetated wadi canyons.80 Much of the Islamic State’s intimidation efforts in rural Kirkuk (i.e., killings and abductions of local farmers) seem purely predatory in intent, aimed at generating protection payments and extorting food and other supplies, as opposed to offensive shaping of the human terrain to support an active insurgency.as Sporadic attempts by the Islamic State to stage mass-casualty IED and suicide bombings in urban Kirkuk also largely tapered off in the latter half of 2020 and have not yet returned.at An Islamic State-planned suicide assault and prison break in Kirkuk city in April 2021 was successfully disrupted by security forces.au In the authors’ assessment, the Islamic State attack cells have been all but locked out of urban Kirkuk—at least temporarily—by security force and popular vigilance.81

In the authors’ view, one key factor in the decline in high-quality rural attacks in Kirkuk (and more broadly) —particularly the steep drop-off in successful outpost overruns—has been the distribution of mast-mounted thermal camera systems among the dense mosaic of Federal Police brigades stationed in the Kirkuk farmbelts and in Samarra in Salah al-Din.82 While Iraqi Federal Police forces still rarely venture outside their outposts after nightfall, when insurgents are at their most active, the camera masts have greatly improved basic situational awareness.83 By distributing camera masts down to small squad-sized rural security posts,84 the Iraqi Federal Police have developed a system of interlocking mortar-fire support bases, establishing what amounts to nocturnal “free fire” zones85 that have reduced the Islamic State’s nocturnal safety and freedom of movement.86 This seems to be reflected in the declining number of successful outpost overruns, and their replacement by less effective nocturnal sniping and stand-off small-arms and rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) harassment, and in particular by the rise of sniping activity dedicated to damaging mast-mounted cameras.87

Diyala

In their May 2020 CTC Sentinel study, the authors tracked a gradual ramp-up of the insurgency in Diyala during the latter half of 2019, culminating in the Q2 2020 with a peak average of 70.7 attacks per month.88 As in most other provinces, Islamic State attacks in Diyala then dropped sharply—to 37 in August 2020—coincident with the culmination of major ISF operations in Diyala.89 Despite periodic fluctuations, overall activity remained at this level with remarkable consistency, averaging 37.8 attacks per month for the Q3 2020 to November 2021 period.90 While well below the high of 2017 (when the Islamic State launched an average of 79.6 per month),91 attacks in Diyala are now consistently falling between the Diyala monthly attack averages of 2018 (26.9) and 2019 (45.8).92

While the overall quality of attacks in Diyala underwent a noticeable decline in the coverage period of this study, the downtrend was less pronounced than in other governorates, with high-quality attacks in Diyala averaging 35.5% of all Islamic State-initiated activity in the latter three quarters of 2020 and 25.3% throughout 2021.93 The category of high-quality attacks that occurred most consistently was targeted killings, which declined from an average of five monthly attacks in the second half of 2020 to 3.5 in 2021.94 av Effective roadside bomb activity nearly halved, falling from an average of 9.8 attacks per month during the latter half of 2020 to 4.9 in 2021.95 Attempted overruns of ISF outposts became rarer, declining from an average of five per month in Q2 2020 to only one per month in Q3 2020 to Q4 2021.96 Even in successful outpost attacks, the majority of security force casualties were typically incurred during follow-on IED strikes on reaction forces.aw

The absence of major outpost overrun efforts by the Islamic State in Diyala was partially offset by persistent sniping and long-range small-arms harassment of road checkpoints and rural security posts.97 Islamic State sharpshooters—frequently equipped with rifle-mounted night-vision opticsax—kept up a near nightly pattern of these attacks, averaging around 22.7 per month in Q3 2020 and Q3 2021.98 While these attacks rarely produced multiple fatalities (at worst, one killed and two injured in severe incidents but more often no killed but rather one or two wounded),99 the sheer volume of sniping activity accounted for a significant portion of all security force casualties in the province.100

As the authors’ noted in their 2016 CTC Sentinel analysis of the Islamic State’s insurgency in Diyala, the varied physical and human terrain and unique sectarian dynamics have long given the Diyala insurgency a somewhat autonomous and self-contained character,101 distinctive from insurgent operating areas more directly connected with the Islamic State’s Syrian and western Iraq systems.102 The variegated local character of each mini-insurgency in Iraq was fully in evidence throughout the new data period surveyed in this study, particularly in Diyala. In contrast to governorates such as Kirkuk or Anbar, where the local insurgencies have been pushed back or confined to remote desert or “deep rural” redoubts,ay the Islamic State has maintained a presence in nearly all of Diyala’s subdistricts, from the Kurdish badlands of Kifri district in the north to the palm groves and highway corridors between Baqubah and Baghdad in the south.103 A particularly noticeable aspect of Islamic State operations in Diyala, which has given the local insurgency some of its dynamic flavor, is the presence of persistently operating mortar, sniping, and bomb-making teams within each local cell across the entirety of the province at the same time.104 az The western suburbs of the governorate center of Baqubah—a historic AQI and Islamic State of Iraq stronghold going back to the mid-2000s105—remains the only urban area in Iraq where the Islamic State still mounts attacks on a fairly regular basis, including under-vehicle bombings and other targeted hits on government and security officials.106

Evidence of Centralized Direction and Resourcing

Among the campaign objectives of the coalition war in Syria and Iraq against the Islamic Stateba was the erosion of the Islamic State’s ability to undertake coordinated multi-city actions in Iraq107 or to mount “external operations”108 against foreign targets in better-secured environments abroad. These kinds of actions typically require a degree of centralized direction and resourcing that exceeds the capabilities of a locally focused rural insurgency.bb As a result, they make good yardsticks concerning the degree to which the Islamic State has been splintered into small, low-impact local cells. Iraqi government intelligence professionals currently view the Islamic State as being highly decentralized,109 with each wilaya controlling most of its own resources—businesses and extortion rackets, cash and gold hoards, and cached explosives.110 Yet in the coverage period of this study, there have been two Islamic State attack campaigns that appear to hint at surviving centralized direction and resourcing: first, efforts to conduct ‘external attacks’ into the well-secured Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) and second, an integrated attack on Iraq’s electricity sector in the summer of 2021, which saw the simultaneous, coordinated spike in pylon strikes across every Islamic State wilaya in northern and central Iraq.111

‘External Attack Planning’ against Iraqi Kurdistan

While not strictly an ‘external operation’ undertaken abroad, one visible example of ongoing centralized direction and external attack plotting appears to be the determined and well-resourced Islamic State effort to penetrate the KRI, which is separated from federal Iraqi provinces by a militarized internal border (known formally as the “Kurdish Control Line”)bc and which enjoys a qualitatively better security situation than Iraq proper.bd According to Iraqi government intelligence professionals,112 the Islamic State’s motive for striking Kurdistan has been to demonstrate that the group can strike anywhere it chooses, even comparatively hardened locations. In this sense, Kurdistan may now play the same role that Islamic State “reach”113 attacks into the “deep south” of Iraq (particularly Basra and the Dhi Qar area of Batha) used to play in demonstrating the group’s ubiquitous access to targets far removed from Islamic State launch pads in northern and central Iraq.114 be

After the liberation of Mosul in 2017, the then Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi tasked a senior operative called Khuzair Abbas Dahlaki to develop an attack campaign against the Kurdistan Region.bf To develop this campaign, during 2018-2019, various patient efforts were made to probe and test Kurdistan Region entry procedures by air travel and land border movement, with persons brought to the KRI capital of Erbil from refuges like Al-Hol camp, Baghdad, northwestern Iran, or cities in southeastern Turkey, including Adana, Gaziantep, and Sanliurfa.115 In many cases, the Islamic State operatives bedded down and went inactive for a year or more before later being contacted and activated.116

In early 2021, the Islamic State’s probing of the KRI was upgraded into an intensified, centrally directed, penetration effort, with effects soon felt on the ground. According to the authors’ canvassing of Kurdish counterterrorism and intelligence agencies,117 this was the result of directives issued by Islamic State leader Amir Muhammad Said Abdul Rahman al-Mawla (also known as Hajji Abdallah), who replaced al-Baghdadi in November 2019.118 Sometime in the latter half of 2020 or early 2021, al-Mawla ordered the Islamic State to form a new Kurdistan Wilayat, seeking to incorporate the remnants of various Kurdish salafi terrorist groups—including Ansar al-Islam,119 the al-Qa`ida in Kurdistan Brigade (AQKB),120 and Kurdish combat units of the Islamic State121 bg—into a single organization. Prior to the 2021 incidents,bh successful attacks in the KRI mostly involved homegrown Kurdish salafi terrorist networks in 2015bi and 2018.bj

The first new Erbil-based attack cell was rolled up in April 2021, with another cell taken down in July, a third in September and a fourth in December 2021.122 In the southern Kurdistan Region, security forces nabbed a small, family-based Kurdish salafi cell in Said Sadiq, near Halabja in January 2021,123 followed by another large group based in Halabja and several other towns in the southern KRI during March-April 2021.124 Another cell was captured in Chemchemal in July 2021.125 Finally, a second larger network was rolled up in the Halabja area in December 2021, though this latter group was made up entirely of local salafi Kurdish militants and had no established operational links with the Islamic State.126

In many respects, the Islamic State penetration effort in the KRI bears a greater resemblance to the European attack plots directed by the Islamic State’s notorious external operations bureau during its terrorist heyday in 2015-2016 than with contemporary insurgent operations in Iraq proper.bk The majority of the 2021 attack plots in the KRI were guided, if not directly controlled, by the Kurdistan Wilayat’s emir, Abu Harith,bl and by Syria- and Turkey-based Islamic State amnis (external operations and intelligence operatives).bm Indeed, the role played by Islamic State networks in southeastern Turkey in enabling operations in Kurdistan stands out as a key feature of the group’s activities in the KRI. Turkey-based facilitators were directly involved in supplying two of the KRI cells with firearms and bomb components.127 Islamic State facilitators, logisticians, and smugglers operating out of southeastern Turkish cities and Istanbul were responsible for moving Islamic State recruits and operatives from Syria and facilitating their entry into the KRI via ‘rat lines’ through Iran and the Lake Van area.128

The cells taken down in Erbil in 2021 were made up predominantly of young Iraqi Arabs,bn either conscripted into the Islamic State during the final phase of its territorial control in Iraq or recruited after its transition back into a clandestine insurgency.129 Each cell was formed by or organized around an experienced terrorist operator.bo In several cases, young recruits without insurgent histories appear to have been deliberately used to minimize the risk of operators being flagged by Kurdish security agencies.bp Target reconnaissance operators entered and left Kurdistan in 2019 without engaging directly with in-place attack cells, though at a later point in 2021, cells were sometimes detected due to their pre-attack foot reconnaissance of potential targets.bq Only three of the cells taken down in Erbil and the southern KRI managed to acquire weapons—crude explosive devices with command wire detonators, suppressed handguns and rifles130—while the remaining five were successfully disrupted by Kurdish counterterrorism agencies before they could arm themselves.131

Overall, Islamic State external operations plotting against the KRI was more determined than successful.br The cells that reached Erbil made the same unimaginative targeting choices that characterized earlier attack plots,bs fixating on hardened or high-visibility government targets such as the Erbil governorate building (aiming to repeat the July 2018 shooter team attack outlined in footnote BJ132) and the touristy bazaars around the citadel in downtown Erbil.133 A specific and to an extent myopic focus on security targets also continued to characterize their target selection.bt The authors began to detect a shift in Islamic State targeting priorities in the KRI in summer 2021, possibly reflective of changed operational guidance from above.bu In addition to their other targets, both cells taken down in Erbil in July and September 2021 also planned to target malls and other locations frequented by foreigners, including military or diplomatic personnel.134

In the southern Kurdistan Region (i.e., Sulaymaniyah and Halabjah provinces), Islamic State cells have traditionally shown a more imaginative and locally informed approach to their target selection, reflecting their roots in local Kurdish salafi mosque networks.bv Islamic State cells taken down in Chemchemal and Halabja were actively planning to conduct assassinations of Asayesh officers as well as kidnappings for ransom of affluent local nationals to fund their operations.bw Southern KRI-based cells entering via Iran or the Kirkuk, Tuz Khurmatu, and Diyala areas have also tended to include more veteran Islamic State operators (usually of Kurdish background) with experience fighting in the insurgency in federal Iraq.bx

The 2021 ‘Pylon Campaign’

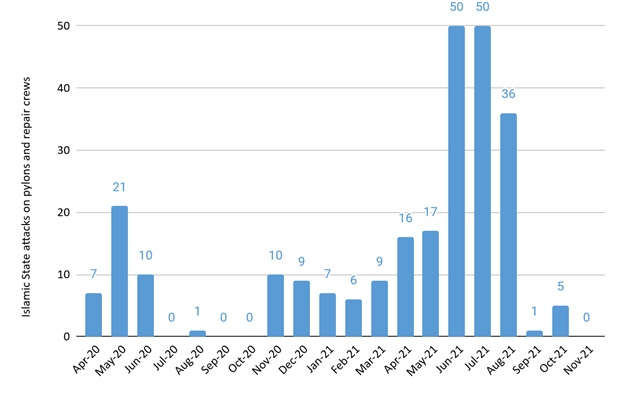

A second potential example of a centrally inspired campaign could be the escalation of attacks against Iraqi electricity transmission and distribution systems from November 2020 onward, and particularly in the summer of 2021. Though it is always difficult to say with certainty who attacked pylons in Iraq and for what primary motive,by careful case-by-case parsing of attack reports produced the assessment below (Figure 8) of pylon attacks (and attacks on pylon repair crews) that can reasonably be ascribed to the Islamic State.bz The campaign bore some resemblance to the late 2004/early 2005 coordinated effortca by AQI to black out Iraq’s electrical system and related water treatment and pumping systems, which included a widespread pylon destruction campaign.

The 2020-2021 pylon campaign reached its crescendo in Q3 2021, at the period of peak heat and electricity demand in Iraq,cb and just a few months ahead of Iraqi general elections in early October 2021.cc The focusing of significant numbers of attacks on pylons is also reminiscent of the centrally inspired but largely decentralized 2019 campaign of crop-burning by Islamic State cells in farming communities across Iraq during the drought of that year.cd Like the crop-burning campaign of 2019, the 2021 pylon campaign by the Islamic State is assessed by Iraqi government intelligence officers to have been an effort to demonstrate the ongoing relevance and potency of the Islamic State and its ability to have more than local or tactical effects.135 “It was an effort to say ‘we are still here,’”136 noted one senior Iraqi intelligence officer specializing in the counter-Islamic State mission. An alternative explanation, given the dearth of Islamic State leadership commentary on the pylon attacks, is that the pylon (and crop-burning) attack series were an example of local Islamic State cells logically identifying pylons as a more attractive target during periods of peak heat, and/or mimicking a growing trend of such attacks.

As Figure 9 shows, the pylon campaign was mostly focused in the provinces of Kirkuk, Diyala, Nineveh, and Baghdad, albeit with every Islamic State wilaya in Iraq taking part.137 Three 400Kv heavy transmission lines were targeted repeatedly: the Iran-Diyala line, the Kirkuk-Qayyarah line, and the Qayyarah-Mosul line.138 Numerous 132Kv local transmissions lines were repeatedly targeted at Udaim and Buhriz (in Diyala’s Udaim and Diyala River Valleys), on the lines that handrail the Kirkuk-Beyji and Kirkuk-Tikrit highways, and at connection points to distribution networks serving towns such as Samarra, Dour, Balad, Muqdadiyah, Khanaqin, Hawijah, Dibis, Al-Qaim, Nahrawan, and Taji.139 In the northern Baghdad belts, the Islamic State struck repeatedly in the Tarmiyah area and with a special focus on the Karkh water treatment plant,140 the same node used in late 2004 to cut off western Baghdad’s drinking water supply.141

The Apparent Weakening in Iraq of the Islamic State: Causality

The prior May 2020 CTC Sentinel Islamic State attack metric study142 highlighted three causal drivers that seem to shape Islamic State attack activity in Iraq. One is the situation in Syria, where civil war conditions gave the Islamic State an influx of foreign fighters, territorial resources, a sanctuary, and access to heavy weapons and explosives.143 The second and third drivers are interrelated and discussed together below: the status of ISF leadership and capabilities, and the degree of international support given to the ISF by the U.S.-led coalition.144 These levels of analysis are still useful ways to approach the issue of why Islamic State attacks levels increase or decline in Iraq, and how they will evolve in the future.

The Role of Syria

On the issue of Syria, the May 2020 CTC Sentinel analysis partially attributed the surge of Islamic State attacks in Iraq in the latter half of 2019 and early 2020 to an influx of veteran insurgent manpower145 ce released by the collapse of the final Islamic State-held pockets in the Syrian Middle Euphrates River Valley (MERV) in March 2019. Does it follow, therefore, that some reduction of this flow might be partially responsible for the stagnation and qualitative decline of the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq in the second half of 2020 and much of 2021?

To better understand the Islamic State operating environment over the border in Syria, it is useful to make a rudimentary comparison of Islamic State attack metrics in Iraq and Syria during the Q2 2020 to Q4 2021 period. The authors drew on a geolocated incident dataset collected using a broadly comparable methodology for collating and categorizing attacks (including a separate category for high-quality attacks, grouped under the same definition).146 There remain persistent issues with building a comprehensive picture of Islamic State activity in Syria, including significant—and probably deliberate—under-reporting by the Islamic State of its attack operations.147 In addition, differences between the information gathering and media environments in Iraq and Syria make drawing a quantitative like-for-like comparison of monthly SIGACT tallies between individual Iraqi and Syrian provinces a challenging exercise. Nonetheless, the authors believe the data on Syrian attack metrics is sufficiently deep to infer a vague relationship between trends in attack activity in Syria and Iraq.

Interestingly, the authors noted a tentative but almost exact inverse relationship between Iraqi and Syria attack trends by the Islamic State.cf The drop-off and then slow decline of the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq after Q2 2020 was exactly mirrored by a sustained ramp-up in Islamic State attacks in adjacent regime-held areas of Syria. For instance, the peak of the Islamic State’s 2019-2020 buildup in Iraq was an exceptionally quiet time for the Islamic State in Syria, with an average of just 20.3 Islamic State attacks per month in regime-controlled areas of Syria from Q3 2019 to Q1 2020.148 As the Islamic State got less active in Iraq in the second half of 2020, there was a gradual increase in Islamic State attacks in Syria,cg to a peak average of 38 attacks per month in Q1 2021. As Iraq briefly saw a partial recovery in the late summer of 2021, Islamic State attacks in Syria got quieter again.ch There is no direct relationship between rises or drops in Islamic State attacks in Iraq and those in Syria (the two theaters are scaled differently, for instance with an average of 135.3 attacks per month in Iraq in Q1-Q3 2021, versus an average of 8.6 attacks per month in Syria over the same period) but the exact inversion is nonetheless intriguing, even if potentially coincidental.ci

Anecdotal reporting from Iraqi intelligence officers with a special focus on the Islamic State149 suggests that they (Iraqi government analysts) believe the ‘upstream’ release of veteran fighters from Turkey, Iran, and Syria into Iraq is still a driver of the operational tempo of the Iraqi insurgency.150 As noted in the Nineveh section of this article, ISF arrest reports151 do suggest a growing pattern of Islamic State combatant and family border-crossings into Iraq from Al-Hol (via Rabia and Sinjar), as well as other less direct routes via the Turkish and Iranian borders with the Kurdistan Region. In the same manner that Mayadeen in Syria was a ‘release point’ for operational Islamic State reserves during the 2014-2019 major combat operations,cj and Turkey was a similar spigot for strategic reserves of fighters,ck it is likely that Idlib, Al-Hol, and Turkey still serve as a reservoir of Islamic State combat veterans who have only been partially remobilized by Islamic State leadership thus far.cl The January 20, 2022, prison assault in Ghweran, Syria, is a reminder that prisons in Iraq and Syria are another potential pooling of reserve forces that the Islamic State may seek to draw upon more regularly in the future.

Iraqi Capabilities and Coalition Support

Within Iraq, it appears clear that ISF operations, backed by coalition intelligence and airstrikes, have been a factor in driving back down Islamic State attacks from their recent apex in May 2020. Kirkuk, Nineveh, Baghdad, and Anbar all witnessed dramatic downturns in the quantity and quality of Islamic State attacks from June 2020 onward.152 In the authors’ view, this decline can be partly explained as a natural reset after a surge of activity during the Islamic State’s Ramadan offensive.cm This spring 2020 Islamic State surge can also be partially explained by the accelerated drawdown of coalition forces from forward advisory locations in north central Iraq,cn the distraction of the coalition effort by militia threats,co and initial COVID-related disruption to ISF security operations in Q1 and early Q2 2020,cp all of which cumulatively had the effect of adding an external ‘artificial’ boost to the Islamic State’s resurgence in the first half of 2020. However, another variable that probably subsequently drove down insurgent attacks was the effective ongoing targeting of senior Islamic State leadershipcq and the large-scale “Heroes of Iraq” phased security offensives launched during Q2 and Q3 2020. Together, all these factors may have acted as a momentum-breaker on the Islamic State’s’ nascent recovery in early 2020.

These operations somewhat differed from previous clearance operations because each focused more deliberately on a specific Islamic State rural redoubtcr and each operation combined mass-mobilization of clearance forces and fire supportcs with intelligence-led raids and strikes on Islamic State mid-level leadership.ct The big downward step-changes in monthly Islamic State attack numbers in Anbar, Kirkuk, and later Diyala track quite closely with the “Heroes of Iraq” series of offensives in those areas. These operations were followed up with other targeted large-scale, coalition-supported operations along the Iraq-KRI disputed line of control, including joint Iraqi-KRI operations such as the “Ready Lion” operation in Makhmour in March 2021cu and numerous smaller follow-on operations in Diyala, Salah al-Din, and Kirkuk throughout 2021.153 Alongside such offensive actions, the whole ISF has gradually built-out some of the rudimentary necessities of counterinsurgency in Iraq, such as fortified outposts, night vision equipment disseminated to outpost level, basic route clearance, auxiliary units manned by local people, and organic mortar support and quick reaction forces.154 The ‘head-start’ in insurgency that the Islamic State was described as enjoying in a December 2017 CTC Sentinel study155 may have finally been eroded by ISF advances. Combined with steadily improving tactical leadership,156 the ISF—though still rough around the edges by international standards—is outfighting the Islamic State in most parts of Iraq.

It may be notable that the Islamic State has best maintained its level of high-quality attacks in areas of Diyala and Salah al-Din that are garrisoned by the least developed security forces with the worst access to coalition intelligence and air support—namely the Federal Police and particularly the units of the PMF that draw support from Iran and that oppose coalition support to the ISF.157 In the authors’ assessment,158 cv Iran-backed militias are dominant in exactly the places that the Islamic State is still the strongest—Sinjar, Baaj, the districts of Daquq and Tuz Khurmatu, Khanaqin, the Iran-Diyala border, Yethrib, the Jallam Desert, the Hamrin foothills, the desert outskirts of Bayji, the Makhul Mountains, and Nukhayb. Thus, some of Iraq’s least disciplined and least resourced troops159 continue to hold the key to stabilization in the areas that the Islamic State is increasingly gravitating toward. In many of these vital “liberated” areas, such militias undertake racketeering that includes smuggling Islamic State fighters and families through checkpoints or taking bribes to allow supplies into Islamic State pockets like the Pulkhana redoubt. In such areas, international and Iraqi media visibility of the real character of insurgency and counterinsurgency is reduced: informal truces abound between outsider militias and Islamic State remnants, for mutual comfort and for profit.160 In the authors’ assessment, terrain under the authority of Iran-backed militias inside Iraq’s borders has arguably become one of the last real sanctuaries that the Islamic State enjoys inside Iraq.cw

The Outlook in Iraq for the Islamic State

The three prior CTC Sentinel Islamic State attack metrics analyses illustrated the undulating pattern of the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq: In the August 2017 issue of CTC Sentinel,161 one of the authors explored the head-start that the Islamic State insurgency enjoyed over security forces that had not yet pivoted to counterinsurgency. The December 2018 CTC Sentinel study162 analyzed a precipitate decline in Islamic State attack activity, and the May 2020 update sought to explain a partial recovery of Islamic State attack capability in late 2019 and early 2020. This new January 2022 study notes new downward steps in Islamic State attack capabilities. The first and most obvious finding of this study is that neither an Islamic State recovery nor further decline is inevitable, as this quartet of studies has already chronicled multiple cycles of Islamic State remission and recovery.

Indeed, conditions in Iraq and Syria will dictate the level of Islamic State attack capability in the future. Short-term conditions—including insurgency in Syria, capabilities and leadership in the ISF, and the level of coalition support—must be carefully monitored in data-led analyses undertaken by experienced analysts inside and outside of the intelligence community. Particular attention should be directed toward the potential that reduced coalition special forces and airstrike activity could create breathing space for a recovery of centralized leadership functions and planning in the Islamic State. If U.S. forces in Iraq have indeed ceased all combat activities, and are not requested by the Iraqi government to provide such support, then there is a strong possibility that Iraq will struggle to conduct time-sensitive strikes using its own air forces.163 This could result in a recovery of the Islamic State’s leadership cadre and its ability to plan more complex operations within a six- to 12-month timescale. Routine day-to-day insurgency would take longer to recover and may be “capped” by other underlying factors.cx

Other long-term drivers such as reconstruction of liberated areas,164 resettlement of displaced persons,165 and reintegration of Islamic State families166 are slower-acting factors that may have less impact on today’s ebb and flow of insurgency, but which will be critical factors—unobvious but vital battlefields—when the insurgency is later viewed through the prism of a generation-spanning struggle against violent extremism.

For now, at the outset of 2022, the Islamic State insurgency in Iraq is at a very low ebb, with recorded attack numbers that rival the lowest ever recorded.cy The Islamic State was so disrupted and weak in 2021 that it was apparently unable to exploit golden opportunities such as the potential for global attention-grabbing attacks during Pope Francis’ daring March 5-8, 2021, visit to Iraq,167 or extensive attacks on religious festivals (like Ramadan) in 2021,cz or even exploitation of reducing levels of coalition air support and periods of poor flying weather.da The pylon campaign in the summer of 2021 demonstrated that the Islamic State still has a glimmer of its old instincts and, in the authors’ speculation, perhaps felt the need to reverse its obvious stagnation with a centrally inspired ‘concept campaign’ (attack electrical power supply in summer), albeit one aimed at one of the most defenseless, vulnerable, but also repairable target sets in Iraq.

One reason that Islamic State leadership needs to occasionally boost its profile is precisely because the attack cells of the movement have largely relocated (in the assessment of the authors) to the depopulated deserts and hills of Iraq. In his December 2017 CTC Sentinel article, Hassan Hassan discussed the growing importance of deep desert sanctuaries for the Islamic State.168 Iraqi intelligence officers likewise stress the Islamic State’s special connection to the desert, with one interviewee noting that the Islamic State was “fully harmonized with the cruel deep desert environment.”169 It is notable to the veteran Iraq-watcher that the Islamic State has been forced into defending corners of Iraq that were never really theaters of conflict in the 2003-2011 period170—in the authors’ assessment, places such as the Makhul and Qara Chaugh ridges, the wadis of southern Kirkuk, the Jallam Desert, the empty Jazeera steppe between Hatra and Rawa, Wadi Husseinat, or the Nukhayb area in Anbar. In the authors’ assessment, these barren fly-blown backwaters are the Islamic State’s main strongholds now.

Yet an insurgency that is primarily constrained to such deserts and other uninhabited environments can fade into irrelevance, ruling only the parts of Iraq that most Iraqis can afford to live without. Hence, in the view of some Iraqi intelligence professionals and the authors, the Islamic State may continue to mount campaigns to remind Iraq of its existence—whether by a regular drumbeat of mortar fire out of the Jallam Desert into the suburbs of Samarra, or with an annual campaign to deny the cities the electricity that is transmitted across Iraq’s deserts. To remain relevant, the Islamic State may decide that it has to come out of the deserts and back closer to the cities, or to hit cross-desert transit systems like roads, pipelines, and electrical grids on a more systematic basis.

In closing, nothing is simple about the cyclical rise and fall of the Islamic State’s insurgent activities in Iraq. Diagnosis of whether an insurgency is strengthening or fading, and why, is a maddening analytical task. In the same manner that a rising tide or a receding tide both create a steady pattern of waves, an analyst always has to ask, “Am I looking at a strong wave, or a rising tide?” or even “Is the tide receding because a tsunami is gathering strength?” Unlike the sea—itself notoriously unpredictable—there are no neat tables to bound the range of high and low tides. In this current study, the authors are not fully satisfied that the known explanatory variables—the ramp-up of the insurgency in Syria, improved capabilities and leadership in the ISF, and the level of coalition support—capture the whole story of the Islamic State’s downturn in Iraq since the early summer of 2020. The authors can feel some “unknown unknown” out there that needs to be identified and analyzed, an “X factor” or “dark matter” that invisibly shapes Islamic State activity levels.

Occam’s razor—the rule that the simplest answer is usually the best—would suggest that the downturn is simply due to the Islamic State’s exhaustion, years of attrition, and isolation from a disillusioned Iraqi Sunni population, with a less pronounced downturn in areas where outsider Shi`a militias have colonized the environment.171 Projecting this trend, the Islamic State will continue to get weaker and concentrated in fewer areas in coming years, and focus on less and less ambitious attacks.db

But the non-linear path of the Islamic State—weaker one year, stronger the next—suggests a less tidy outlook. The Islamic State’s apparent gradual diminishment in Iraq could to some extent involve deliberate conservation of offensive capacitydc—based on the Islamic State’s professed strategic patience and belief in outlasting enemies172—resulting in a ‘withholding’ of attacks in which the Islamic State was not fighting as hard as it could in 2020 and 2021.dd As CTC Sentinel authors Haroro J. Ingram, Craig Whiteside, and Charlie Winter have noted, the Islamic State has a proven capability to absorb tactical defeats, encyst in new safe havens, partially hibernate, learn from mistakes, and return to fight new campaigns.173 As this study has observed, in Iraq the Islamic State presently uses only a fraction of its available explosives and seems to deliberately attempt very few suicide operations or urban attacks, but given a cadre of new high-quality operators and the decision to resume such attacks, it could return to these activities and find cities as vulnerable as, or more than, in the past.de

This study has noted that the Islamic State can, with suspicious ease, periodically reactivate bombing cells in parts of Iraq for special purposes, such as the pylon campaign. Further study should investigate whether the Islamic State has the intention and capability to reactivate an under-utilized reserve of experienced manpower scattered in sleeper cells across southeastern Turkey, Syria, Iraq, and beyond. All these conundrums suggest that analysts should leave a wide margin that some fraction of the Islamic State’s decline in Iraq is, in fact, dormancydf or latencydg that could be reversible under the right conditions.