Forget the pipelines. The growing détente between Eastern Mediterranean neighbors Israel, Cyprus, and Greece is being leveraged mainly to counter Turkish influence and expand Washington’s presence in the region.

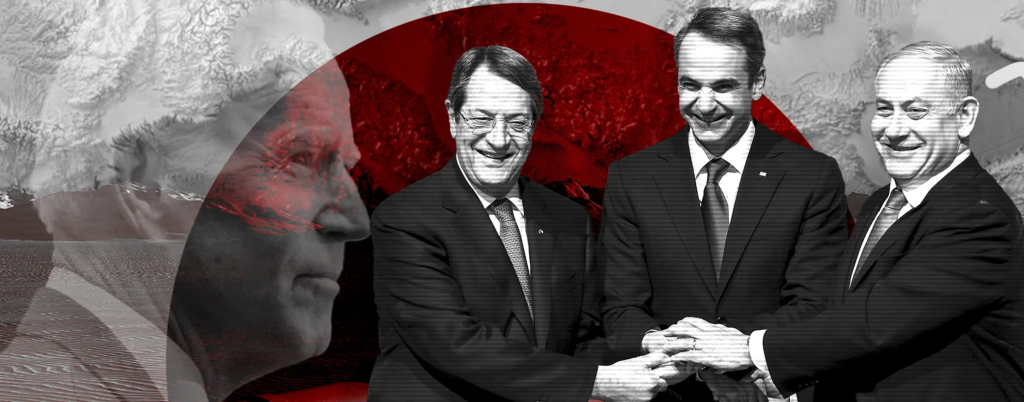

On 4 September, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus met at their ninth tripartite summit to endorse the wave of Arab normalization with Tel Aviv. The trio also committed to determining the process and logistics for exporting stolen Palestinian gas to Europe within the next six months.

For years, Israel, Greece, and Cyprus have diligently deepened their geostrategic partnership across multiple domains, with a primary focus on energy and security collaboration in the Mediterranean Sea region. The group, formalized as the troika in 2015, convenes annually to bolster their cooperation in all areas.

The tripartite bloc’s origins can be traced back to 2013 when their respective energy ministers convened in the Cypriot capital Nicosia to affirm their intention to collaborate on the construction of the EuroAsia Interconnector. The ambitious project would connect the electricity grids of Cyprus, Israel, and Greece via a high-voltage undersea DC transmission system boasting a capacity of 2,000 MW (currently under construction).

In addition, the trio has initiated another joint project – the Eastern Mediterranean pipeline, known as EastMed – which is designed to transport gas from Cyprus and Israel to Greece and onward to Europe. This controversial route has elicited strong reactions from various states at various times and even skepticism over its feasibility.

Greece’s geostrategic significance

On 20 March, 2019, an American delegation participated in the trio’s Foreign Ministers Meeting held in Jerusalem, where they inaugurated the 3+1 Forum, a construct devised to include the United States with the three bloc countries.

Washington’s involvement expanded the cooperative framework to encompass not only energy issues, but also security, defense, and shared objectives. During this meeting, the three parties reaffirmed their joint commitment to “increase regional cooperation; to support energy independence and security; and to defend against external malign influences in the Eastern Mediterranean and the broader Middle East (West Asia).”

This cooperation is part of a larger US strategy to recruit Athens as a key ally in the region. As relations with Turkiye soured over the past decade, Washington has found in Greece another NATO ally it can rely on to achieve its ambitions.

For the Americans, Greece is crucial in addressing the competitive dynamics among global and regional powers in both Southeast Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean.

Leveraging existing Greek concerns about Turkiye’s naval activities and increasingly belligerent rhetoric, the US has strategically bolstered its military presence in the country – with the potential of becoming a de facto US military hub, as suggested by the Turkish president.

Tensions between Ankara and Washington have also sparked debate about reducing dependence on US military bases in Turkiye.

Increasingly, it appears that Greece represents the linchpin in Washington’s strategic blueprint for the Eastern Mediterranean, serving as a pivotal launching pad for US forces and facilitating their reach into West Asia, North Africa, and Europe.

For the Americans, Greece yields an advanced vantage point for exerting control over the Mediterranean and Aegean Seas, a particularly vital position in light of China and Russia’s expanding influence in the region.

EU’s gas export dilemma

Greece’s active engagement in regional alliances alongside US allies like Israel also offers an opportunity to forge a wider security framework. This approach allows Washington to distribute its geopolitical burdens equitably among allies while the US grapples with its core challenges of Beijing and Moscow.

As tensions escalate over offshore gas rights in the Eastern Mediterranean, these countries have sought to further strengthen their alliance. With the endorsement of the Trump administration, the tripartite group inked a 2020 memorandum of understanding which finally greenlit the EastMed project.

As envisioned by its stakeholders, the EastMed pipeline will stretch over approximately 1,900 kilometers and plunge to depths of up to 3 kilometers, ranking it the world’s longest and deepest subsea pipeline. Those ambitious specs, in turn, present substantial challenges during both the construction and maintenance phases.

With an estimated construction cost of $6.2 billion, the project also becomes economically questionable, particularly when compared to the $1.5 billion price tag for a pipeline from Israel to Turkiye.

In addition, the pipeline project has become a considerable source of regional friction. Turkiye, for instance, remains staunchly opposed to any exploration activities in the Eastern Mediterranean, and any gas transport project to Europe that does not include its participation. These considerations led the US to announce its withdrawal of support for the project early last year.

With Europe actively seeking alternative natural gas sources to reduce dependence on Russian energy – coupled with large gas discoveries in occupied Palestine, Cyprus, and Egypt – deciding on an export route for Eastern Mediterranean gas has become a pressing concern for the EU. In 2022 alone, approximately 270 billion cubic meters of natural gas were discovered in the waters of Palestine, Cyprus, and Egypt.

A conduit for normalization

The Eastern Mediterranean gas export route was, therefore, one of the hot topics discussed in September’s tripartite summit. According to reports, a decision will be made on the route of exporting Cypriot gas and Palestinian gas within the next three to six months. To date, there are three proposed routes for exporting Palestinian gas:

The first of course is the EastMed pipeline, an extensive – and expensive – project connecting the Eastern Mediterranean gas fields, including those in Palestinian waters, to Europe through a high-capacity subsea pipeline.

The second route under consideration is a direct pipeline to Cyprus. Nicosia introduced the proposal in June for a 300-kilometer Qusayr pipeline that would link Palestinian gas fields in the Eastern Mediterranean to a gas liquefaction facility in Cyprus. Following liquefaction, the gas would be transported via ships to European destinations.

The third proposed route is a pipeline to Turkiye. This option entails an underwater pipeline connecting Turkiye to the natural gas fields in occupied Palestine. From Turkiye, the gas would be further transported to southern European countries.

The summit’s final communiqué underscored the bloc’s determination to expand its cooperation beyond its current boundaries, reaching out to countries in West Asia and on to India. Through the Arab-Israeli normalization agreements, the three parties believe they can connect and collaborate more easily with other regional players and groups.

Chief among these is the Negev Forum, which encompasses Bahrain, Egypt, Morocco, the UAE, the US, and Israel. Clearly, Tel Aviv aims to leverage its agreements with Greece and Cyprus to encourage economic cooperation with Arab states.

The summit statement was clear:

“The strengthening and widening of the circle of peace between Israel and the Arab world, unthinkable only a few years ago, holds the promise for a more secure and prosperous region, and we are committed to encourage and support this process.”

During the recent summit, the participants also raised the possibility of inviting India to attend the next trilateral bloc meeting. The move is arguably US-driven and part of Washington’s strategy to attract India’s involvement in the region as an Asian rival to China. Although the two are both core members of BRICS and the exclusive Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the US is now employing all its allies in its geopolitical and economic competition with China.

A Greek tragedy

Despite Greece being the last EU member to establish full diplomatic relations with Israel, which it officially recognized in 1990, its eagerness to establish a US partnership to counterbalance Turkiye’s regional influence, has brought it closer to Israel.

This aligns well with Washington’s goal of relying less on a Turkiye under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s leadership. Interestingly, the primary beneficiary of this convergence of interests is Israel, as its relations with Greece and Cyprus continue to strengthen through collaborative projects like the Eastern Mediterranean gas export initiative.

Recent developments, such as the US-backed India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) to transport cargo to Europe via Greece (excluding Turkiye) and Israel’s ongoing refusal to agree to gas exports through Turkiye, are bound to elicit a strong reaction from Ankara.

Washington is well aware of the provocative nature of these projects for Turkish authorities, and by championing them, is potentially signaling a shift in its relations with Turkiye.

The budding alliance between Athens, Nicosia, and Tel Aviv, meant to enhance their collective security and energy needs, has thus far mainly served to extend Washington’s reach into this crucial crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. But as recent US policies have demonstrated, the Eastern Mediterranean, West Asia – even Europe – do not matter nearly as much as Washington’s fixation on China and Russia.