Beijing is Poised to Dominate the Low End of the Arms Market

Shortly after Russia’s annual military expo concluded in August, Alexander Mikheyev, the head of the country’s state arms export agency, predicted that revenues from Russian arms exports in 2022 would be down 26 percent from last year. Russia remains the world’s second-largest arms exporter after the United States, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute; it would take a far larger drop in revenues to change that. But it has become clear that since Moscow’s disastrous decision to invade Ukraine in February, the Russian military’s need to replace its own equipment, U.S.-led sanctions, and buyers’ concerns about Russian equipment’s performance on the battlefield have reduced Russia’s ability to export weapons.

While Washington dominates the global market in high-end, high-tech weapons, Russia has carved out a place for itself as the world’s leading supplier of the capable and cost-effective but lower-tech weapons that are sometimes described as “value arms.” These include new variants of Soviet and Russian equipment such as T-72 and T-80 tanks, towed artillery pieces like the D-30, self-propelled howitzers like the 2S1 Gvozdika and 2S19 Msta, self-propelled multiple rocket launchers such as the BM-27 Uragan and BM-30 Smerch, the S-300 missile defense system, and armored personnel carriers such as the BMP-3 and BTR-70. Although lower-income countries such as Myanmar, Zambia, and Zimbabwe buy only weapons in this category, middle-income countries such as Brazil, India, and Thailand that participate in segments of the high-end market also purchase large supplies of value arms. In 2022, defense spending by the mainly African, Asian, and Latin American countries that compose the value market totaled $246 billion.

Since American firms typically do not compete in the value arms market, Russia’s difficulties have created a vacuum. And the country poised to fill it is China. If left unchecked, Beijing could use defense equipment sales to build stronger relationships with ruling elites and to secure foreign basing, potentially restricting the U.S. military’s capacity to maneuver across the globe. Expanding Chinese arms sales would undermine U.S. influence in the ongoing geostrategic competition. But that outcome is not yet inevitable. There is still time for the United States and its allies to provide substitutes for Russian weapons at affordable prices and thus to thwart China’s ambitions.

POISED FOR DOMINATION

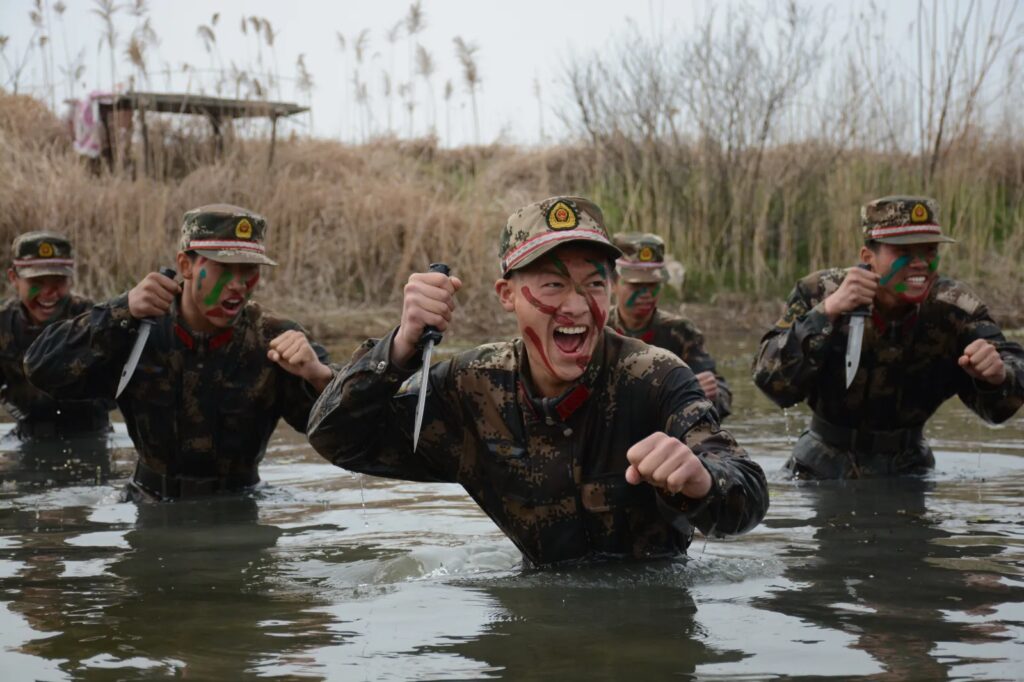

China boasts six of the 25 largest defense firms in the world. Although China’s current five percent share of the global arms market is significantly lower than Russia’s 19 percent, this indicates China’s potential to expand its market share. China has several distinct advantages that could allow it to dominate the value market.

China’s approach to arms exports is transactional, unencumbered by concerns about human rights or regime stability. China exchanges weapons not only for financial renumeration but also for access to recipient states’ ports and natural resources. In part by supplying value arms like radars, missiles, and armored vehicles to Venezuela and Iran, for example, Beijing has secured steady access to oil from those countries.

China’s approach to arms exports is transactional, unencumbered by concerns about human rights or regime stability.

China’s experience as a licensed producer of certain kinds of Russian military equipment has increased its customer appeal in the value arms market. For example, after China and Russia signed a strategic partnership agreement in 1996, China was licensed to produce its Russian Su-27Sk Flanker B fighter aircraft. Such arrangements have helped make China the second-biggest supplier to Angola, Nigeria, and Uganda and the biggest supplier to Bangladesh and Myanmar—all places where Russia does brisk business.

Even before Russia’s present difficulties, China had diversified its product offerings to replicate Russia’s strategy of producing affordable substitutes for high-tech Western armaments. Most sub-Saharan African countries operate Chinese weapons, but sales to the region constitute only 19 percent of Chinese exports. More than 75 percent of Chinese exports go to Asian countries where China has begun to expand its industrial production network. Pakistan, for example, now co-produces many Chinese weapons systems, such as the Al-Khalid tank and the JF-17 Thunder fighter jet. More recently, in addition to value arms, China has begun selling higher-end weapons systems to prominent clients: in April, it began selling antiaircraft missiles to Serbia, and in June, Argentina signaled interest in JF-17 fighter jets. China is now the world’s largest exporter of drones, and it has begun to sell its Wing Loong and the CH-4 models to customers that used to buy U.S., French, British, and Russian drones—a list of countries that includes Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

China’s long tradition of acquiring foreign technology gives it a leg up in the value market. An official approach called “introduce, digest, absorb, and re-innovate,” rolled out in 2006, encourages Chinese companies to “to acquire foreign technology and then ‘re-innovate’ those products for domestic markets.” These efforts reduce development costs and help improve the quality of Chinese-produced weapons.

A final advantage concerns rare earth elements, a group of 17 metals including erbium and neodymium, which are critical to manufacturing some of the most modern defense equipment. Since mining and processing rare earth elements produces high volumes of toxic waste, China’s lax environmental regulations have helped it to dominate the global trade in these metals. China has restricted sales of rare earth elements to coerce other countries in the past and threatened to restrict sales to the United States in 2019 in response to then U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariffs on Chinese goods. If China were to restrict exports of rare earth elements to the United States, it could hinder production of high-end systems, including the F-35—not to mention guided munitions, aircraft, and the many other technologies that rely on these minerals for their production.

RISKS TO THE U.S.

Expanded Chinese participation in the value arms market could expand its geopolitical reach while reducing U.S. access to foreign ports and bases. China has already used arms sales to secure military basing rights and to reorient recipient governments away from U.S. influence. The Solomon Islands’ refusal to allow port calls by American and British naval vessels in August, just a few months after signing a security agreement with China in April, could herald a new era in which U.S. global maneuver capability is increasingly challenged.

To thwart China’s ambitions in the value arms market, the United States should help its partners develop production capabilities of their own. U.S. firms need not directly participate in the value arms market, but the U.S. government can work closely with allied nations to meet that market’s needs.

To allow the United States and its allies to compete in the value market, the U.S. should reform portions of the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), a regulatory regime that restricts the export of military technologies. While protecting the United States’ technological advantage remains critical to national security, the United States should establish ITAR sunsetting parameters to facilitate the export of older weapons and to allow its partners to begin producing them. To facilitate partnerships between U.S. firms and foreign defense industries, the United States should also create a petition system to remove ITAR restrictions on individual products. American engagement with allied manufacturers allows the United States to retain a presence in the value market when direct participation is difficult. Targeted ITAR reforms could facilitate the formation of a coalition of arms-producing states that outcompetes China for the value market.

To thwart China’s ambitions, the U.S. should help its partners develop production capabilities of their own.

The United States should provide incentives—such as tax cuts and write-offs—for U.S. firms to co-produce affordable quality weapons with partner countries. The United States could work with South Korea and India on improving their Golden Eagle and Tejas jet trainer and light combat aircrafts, South Korea’s K9 Thunder howitzer, and India’s light tank for the value market.

The United States should actively support American firms’ participation in the value market. In 2018, for example, the Defense Department decided not to purchase Textron’s Scorpion fighter, a jet designed to perform light attack and armed surveillance. When the U.S. Air Force stopped working on its air certification, Washington unintentionally signaled its lack of commitment, likely pushing away international clients. Although the Pentagon allegedly wanted a turbo-prop aircraft that was cheaper to procure, the Scorpion was relatively inexpensive to operate and likely competitive on the value market. In this case and in others, it would have been helpful if the U.S. government had certified its airworthiness and the Commerce Department advocated with foreign governments.

U.S. engagement in the value market will also strengthen its own supply chain and industrial base by supporting partners’ industries, diversifying U.S. suppliers, and politically engaging value market importers. In 2022, the National Defense Industrial Association, a trade association for U.S. defense contractors, rated the U.S. industrial base as unsatisfactory for the first time. The blame went to a number of factors: supply chain disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, skilled labor shortages, shaky budgetary commitments from Congress, and cybersecurity-related vulnerabilities. The above proposed reforms will facilitate U.S. defense industrial base resiliency, strengthen allies, and counter Chinese expansion.

China’s growing grip over the value market will allow it to challenge U.S. interests by increasing China’s access to policy elites in the global South, widening access for its military via bases and port facilities, and supplementing its defense industry. By deepening industrial cooperation with its allies and encouraging them to join the value arms market, the United States can not only gain a strategic advantage over its main rival but also strengthen bonds with its friends.