Understanding current market or economic conditions and the interests of various competitors is not sufficient to adequately comprehend ongoing geopolitical processes. This is especially true for the Middle East and the Balkans. A deep analysis and deconstruction of existing regional systems are needed to identify elements of interdependence and develop possible responses to all sorts of challenges.

What unites and what divides the Middle East and the Balkans? Not only is there a longstanding conflict between Christian and Muslim actors on the one hand, but, on the other, there is also a syncretic coexistence of Islam and Christianity developed within the framework of the mutual influence of the various peoples’ cultures. This is not only a matter of proximity or distance. One can look at these regions from different angles depending on the chosen vantage point.

In the opinion of the author, serious attention needs to be paid to two things. Firstly, there is the system of external influences which the two regions were established under and which continue to be affected by. The second factor is the common historical and political heritage which, when appealed to, offers solutions for modern issues.

In discussing the impact of these factors, it is necessary to begin with the process of political imagination that British strategists employed when establishing the project of the Middle East and which they have imposed on the rest of the world. This theory and its practical implementation is known as “Orientalism” which Edward Said describes in detail in his book. The British Empire justified its control of the region under the pretext of transferring western concepts of political governance to other countries’ peoples as the only correct and acceptable way. Thus began the expansionist policy of the West. Ralph Peters quite reasonably noticed that when the United States pursues its foreign policy objectives, it first sends hamburgers from McDonalds and Hollywood cinematic productions to other countries. Only then, if necessary, do bullets and bombs become the tools of foreign policy.

In any geopolitical confrontation, the most serious consideration should be given to the self-consciousness of nations and their elites. This quite ordinary remark demonstrates how political geography dominates other ideas. Is this region, the Middle East, understood by the nations of the Persian Gulf and the Red Sea themselves as the “East?” Why have the rich countries of the Persian Gulf not faced the process of decolonization as happened in India?

Although Islamic law and a special hierarchy of power predominates in the region, this does not prevent most Arab countries from being integrated into the overall global system arranged according to Britain, or rather the ideas of Scottish liberalism.

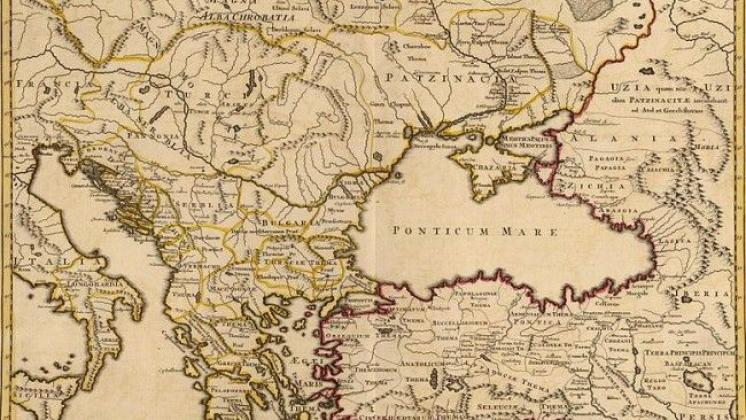

Another explicit element of Westernism can be found in the complex science of geopolitics. The classical authors of geopolitics insisted that there exists the World-Island with Heartland in the center and the “inner crescent” outlining the borders, known as Rimland, which includes the Balkans and the Middle East. The World-Island as a whole is surrounded by the outer crescent.

Nicolas Spykman, in reviewing Halford Mackinder’s main positions, believed that Rimland is more important than Heartland given its ambivalent nature: this coastal zone faces the Eurasian continent, but is equally open to the outer seas.

Zbigniew Brzezinski continued this line by demonizing the region under consideration, turning it into the Eurasian arc of instability beginning in the Balkans and ending in the mountains of China. In The Grand Chessboard, Brzezinski also discusses the Islamic factor which is directly connected to the problems of this arc, seeing as how part of the Balkans, the Caucasus, and Central Asia up to the Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region are populated by Muslim nations.

Is there any trace of Samuel Huntington and his concept of the clash of civilizations evident here? If yes, then in this case, the types of civilizations introduced by him bear a clearly religious connotation. Thus, the Westphalian model, based on the separation of secular and religious power, is a farce. Therefore, the results of the Enlightenment should be questioned and revised.

Meanwhile, one of the world’s conventional theories of international relations, realism, is also a product of the early Italian Enlightenment. The founding father of this theory and the notion of “national interest” is considered to be Niccolo Machiavelli who promoted these ideas in his book The Emperor. But are these views authentic? Machiavelli derived many theses from the works of the Byzantine work Strategikon whose author is known as Maurice or pseudo-Maurice. It is unimportant whether this work belonged to Emperor Maurice or to one of his generals. What is important is that this interesting Byzantine theory of realism guided the world’s leading power. The Byzantine Empire once covered considerable area and pursued quite successful policies. Moreover, Byzantium’s confrontation with wars, religious conflicts, internal contradictions, and the Great Migration can be compared to the current crisis, especially the immigration crisis, in Europe.

The Byzantine heritage can seriously help one to find an appropriate policy in solving many existing problems and challenges. This is not only reducible to the Christian Neoplatonic School which developed metaphysical doctrines far surpassing issues of administration and management. It is also unavoidable to view Islamic philosophy in isolation from the Byzantine Empire. Although mystical Islam and its legal schools have experienced serious changes, a number of recognized Muslim scholars, such as Ibn al-Arabi, have utilized and developed many Neoplatonic ideas. Ibn al-Arabi’s doctrine of the Unity of Being (waḥdat al-wujūd) was addressed not only to mystics, but also to Muslim jurists and theologians, i.e., those who in fact worked on public policy issues and international relations.

Those who, regardless of Christian or Muslim origin, master working with apophatic theology, the attributes, names, and characteristics of God, and the timeless processes of theophany and the phenomenon of pre-eternity will ultimately be better equipped to understand the interests and needs of the other side than those who receive a secular education at Oxford or Harvard according to the Anglo-Saxon templates of the liberal tradition that is essentially anti-religious.