What’s new? The post-9/11 U.S. “war on terror” expanded under three presidents, with Congress asserting little oversight after enacting a broad 2001 authorisation. The Biden administration has dialled back operations somewhat. Yet the conflict’s legal underpinnings remain in place, while congressional efforts to reassert control over the use of force have stalled.

Why does it matter? Given the reach of U.S. military operations, the U.S. government’s safeguards concerning the use of force have implications for international peace and security. Meaningful inter-branch oversight would provide policymakers and the public insight into the costs and benefits of conflict, while improving democratic accountability on matters of war and peace.

What should be done? Congress should devote more attention to oversight of the use of force. While major structural reforms may not be realistic in the short term, lawmakers could take a number of practical steps that would help them better elicit and analyse information from the executive branch on U.S. wars.

Executive Summary

After the 11 September 2001 attacks, the U.S. Congress enacted a broad use-of-force authorisation that four successive administrations have relied on to mount a globe-spanning military response aimed at al-Qaeda and affiliated groups. The operations conducted within this framework, widely referred to as the “war on terror”, highlight not only the U.S. military’s power but also the importance of the processes by which the U.S. government decides on whether, where and how to use it. Although the U.S. constitution contemplates that the executive and legislative branches will share power on matters of war and peace, for decades the former’s role has expanded and the latter’s shrunk. In recent years, the U.S. Congress has shown halting signs of reasserting itself – questioning U.S. involvement in the Yemen conflict, trying to repeal the outdated 2001 use-of-force authorisation, and considering how to overhaul the allocation of war powers between the executive and legislative branches. While these efforts have stalled, Congress can and should take smaller practical steps in working to reclaim its constitutional prerogatives.

The U.S. constitution divides war powers between the legislative and executive branches. The constitution’s framers intended this separation of powers to be a conflict prevention measure. The U.S. constitution empowers Congress, not the president, to declare war, and in doing so contemplates that such weighty decisions will be subject to deliberation in a large representative body rather than left to the judgment of a single person. While the constitution has always been understood to allow the president room to use force without congressional assent, that flexibility was originally envisaged to be reserved for cases of self-defence. In the post-World War II era, however, the congressional role has receded, as the executive branch has asserted increasing unilateral authority. While there have been efforts to curb this trend – for example, through enactment of the War Powers Resolution of 1973 – these have largely fallen flat as all three branches of government have worked to neutralise provisions that would have restored constitutional balance.

The expansion of the executive branch’s unilateral authority has been particularly striking in the period following al-Qaeda’s 11 September 2001 attacks on the United States. This authority derives in great part from the broadly worded use-of-force authorisation that Congress enacted just following the attacks. This statutory authorisation permits the use of force against the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks and those who supported or harboured them. It contains no geographic limits and no expiration date. Amid the shock of the attacks, only a few critics worried about how this instrument might become something close to a blank check for the executive branch to define the contours of the war that would follow.

But as the war on terror dragged on, and the U.S. both expanded its military counter-terrorism operations and became embroiled in new conflicts in Libya, Yemen and elsewhere, more people felt these concerns, which began gaining traction in Congress itself. Over the last five years, congressional resolutions to end U.S. involvement in Yemen’s fractious civil war and restrain military action against Iran – as well as draft legislation to reform the War Powers Resolution of 1973 and repeal or reform outdated use-of-force authorisations – sent an increasingly salient signal that Congress was starting to think more seriously about reasserting its war powers.

Those efforts have largely stalled, however. It appears that the war powers debate has quieted at least in part because President Joe Biden curtailed some elements of the U.S. war on terror. His administration took the very significant step of withdrawing U.S. troops from Afghanistan and has reduced the number of airstrikes in various theatres. It has also taken the war off the front pages by generally behaving less erratically than the administration of President Donald J. Trump – who threatened North Korea with “fire and fury” and risked confrontation with Iran by killing Qassem Soleimani, head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’ Qods Force. Against this backdrop, the zeal in Congress for pursuing legislative checks on presidential war powers has waned somewhat

” Congress and the U.S. public should not be lulled into complacency by the slower operational tempo that has characterised the Biden administration’s approach to the war on terror. “

But Congress and the U.S. public should not be lulled into complacency by the slower operational tempo that has characterised the Biden administration’s approach to the war on terror. So long as the 2001 Authorisation for Use of Military Force (AUMF) remains on the books, and the structure of war powers remains unreformed, future presidents will be free to expand the post-9/11 conflict once more and, in general, to wield war-making authority too unilaterally and unaccountably.

While it will take time to build sufficient political will for major legislative reforms – like placing responsible limits on the 2001 AUMF or reinvigorating the War Powers Resolution of 1973 – this is not a reason for inaction. Nor is the possibility that mid-term elections will bring a change of power in one or both houses of Congress. That change would put the Biden administration’s Republican adversaries in control and set the stage for two years of heavily politicised inter-branch battles. But even so, there are smaller practical steps that would bolster Congress’s role in matters of war and peace, which are not necessarily out of reach and in any case worth trying to take.

The overarching goal of these practical measures should be for Congress (and in most cases, by extension, the public) to get more and better information about the nation’s wars. Congress can play a meaningful role in decisions about the use of force only to the degree that it knows where and how the president is wielding U.S. military power. Yet, too often, the executive branch does not divulge this information – or does so only incompletely, or when its relevance has diminished. The fact-finding mechanisms in the congressional toolbox, including hearings, reporting requirements and informal inquiries to executive branch agencies have a mixed record of effectiveness. Administrations of both parties have deployed a range of techniques to stonewall congressional inquiries, from citing dubiously broad legal protections to evading compliance with statutory reporting requirements through strained or barely credible interpretations. As a result, Congress is left in the dark both with respect to how the executive branch is using force and how the executive conceives of its own war powers.

Congress faces additional challenges, some of its own making, in obtaining information and analysing what it does receive. The public often pays scant attention to the post-9/11 U.S. wars, which have taken place far away and entailed little disruption to most citizens’ lives. Members of Congress accordingly are under little pressure to exercise oversight, see little if any political benefit in doing so, and indeed perceive substantial political risk in asking hard questions about military operations that are often still framed as protecting the homeland from a global terrorist threat. Unnecessary barriers to the flow of information within Congress also stymie effective oversight, as does a shortage of staff with deep expertise and the time necessary to properly scrutinise the executive branch’s activities.

Fixing this situation, in the interest of both enhancing safeguards against imprudent conflict and promoting greater democratic accountability for matters of war and peace, should be the responsibility of both the executive and the legislative branches. For its part, the executive branch should commit to work with Congress to facilitate oversight, as such cooperation is required to bring the post-9/11 wars to a close. To this end, the White House should, among other things, release documents requested by Congress relating to the use of force, publicly share the list of groups that it deems covered by the 2001 AUMF, and publicly explain the legal and factual bases upon which it added them to the list.

But in the likely event the executive branch prefers to guard the prerogatives it has built up over several decades, the burden of this effort is likely to fall largely on Congress. Assuming that it continues to face a recalcitrant executive branch, Congress should adapt its techniques accordingly. It should more routinely ask for closed-door, transcribed briefings employing techniques it has honed of late to elicit the information it needs away from the camera’s eye. When seeking information from the executive branch, it should press to receive the underlying materials – internal communications and legal opinions – rather than derivative reports, which too often fail to present a full picture. For matters of sufficient magnitude, lawmakers should also be prepared to delay confirmation of nominees or enact funding restrictions as leverage if the executive branch digs in its heels.

As Crisis Group has previously noted, Congress is not always a brake on war-making. It did, after all, enact the 2001 AUMF, as well as authorising the Vietnam and Iraq Wars. Still, if U.S. political leaders are to learn the lessons of past conflicts, then they need to be accountable for the nation’s wars. That is only possible if they have timely, accurate information about where those wars are being fought.

While incremental measures to make Congress better informed about matters of war and peace would not obviate the need for major legislative reforms, they would move Congress in the right direction. They would both help legislators to shape the U.S. role in current conflicts and inform efforts to pursue future reforms. Proponents should not be dissuaded by a fractious political environment from urging members on both sides of the aisle to pursue these measures. After years of turning away from its responsibilities, Congress needs to start rebuilding its war powers now, even if it is only one modest step at a time.

Washington/Brussels, 26 October 2022

I. Introduction

After twenty years of continuous war – including the post-9/11 militarised counter-terrorism campaign known as the “war on terror”, the 2003 invasion and occupation of Iraq, involvement in elective wars in Libya and Yemen, as well as moments of high tension with Iran – the U.S. Congress has taken halting steps to reassert itself in matters of war and peace. President Donald Trump faced strong, though unsuccessful, bipartisan pressure from lawmakers to end U.S. military support for the Saudi-led air war in Yemen and abjure the use of military force against Iran.[1] More recently, bipartisan coalitions of lawmakers have pushed to reform 50-year-old war powers legislation and to replace open-ended and outdated authorisations for military operations against al-Qaeda, the Islamic State (ISIS) and their affiliates in the U.S. war on terror.[2]

Yet these legislative efforts to repeal war authorisations and enact structural war powers reforms are long-term initiatives that, for the moment, have stalled. In the meantime, there are steps Congress can take now (ideally with the support of the executive branch) that would improve its capacity to oversee U.S. participation in conflicts and to shape more substantial war powers reforms down the road. These measures, which can mostly be accomplished without legislation, are focused on improving the flow of reliable information to Congress.

This report examines why such measures are needed and how they could help. It describes how, as the executive branch has asserted increasingly unilateral war powers with congressional acquiescence, it has also avoided giving timely information to Congress about U.S. operations – including, most recently, major counter-terrorism engagements in new or emerging theatres of conflict. It also looks at how to improve communication between the two branches, procedures that might allow members of Congress to more effectively glean and analyse information, and mechanisms legislators could use to elicit information if the executive branch resists cooperation. The report draws upon scholarly literature, think-tank reports and interviews conducted largely between July 2021 and August 2022 with more than three dozen current and former congressional staff members and executive branch officials (including members of Crisis Group’s staff who previously served in government and contributed to the report).

[1] Catie Edmondson, “U.S. role in Yemen war will end unless Trump issues second veto”, The New York Times, 4 April 2019; Senate Joint Resolution 68, “A Joint Resolution to Direct the Removal of United States Armed Forces from Hostilities against the Islamic Republic of Iran that Have Not Been Authorized by Congress”. This resolution passed in both houses of Congress in the spring of 2022. President Trump vetoed it, however, and the Senate failed to muster the two-thirds vote it would have needed to override the veto.

[2] Brian Finucane, “Putting AUMF repeal into context”, Just Security, 24 June 2021; Tess Bridgeman and Stephen Pomper, “A giant step forward for war powers reform”, Just Security, 20 June 2021.

II. Presidential War-making Requires Oversight

The U.S. presidency’s war powers have been on a general, though not uninterrupted, upward trajectory since World War II.[1] The aggrandisement of presidential war-making authority is a result of Congress delegating power as well as the executive branch arrogating power to itself.[2] In the past two decades in particular, Congress has given the executive branch a strikingly wide berth to define the scope of a global counter-terrorism campaign widely referred to as the “war on terror”.[3] The primary legal basis for this war is the 2001 Authorisation for Use of Military Force (hereafter, the 2001 AUMF), which empowers the president to use all “necessary and appropriate” force against actors involved in specified ways with the attacks of 11 September 2001, as well as those harbouring them.[4] As Crisis Group has written previously, this authority has proven quite elastic in practice.[5] Moreover, Congress has generally shown little appetite for checking the expansion of the executive branch’s powers through legislative reform, often in effect ratifying the executive’s decisions after the fact through supportive appropriations and other legislative acts.[6]

[1] See, for instance, Arthur Schlesinger, The Imperial Presidency (Boston, 2004); John Hart Ely, War and Responsibility (Princeton, 1995); David Baron, Waging War: The Clash Between Presidents and Congress, 1776 to ISIS (New York, 2016); and Michael Beschloss, Presidents of War: The Epic Story, from 1807 to Modern Times (New York, 2018).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Crisis Group United States Report N°5, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, 17 September 2021.

[4] Authorization for Use of Military Force, Pub. L. No. 107-40, 115 Stat. 224 (2001). (“That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons, in order to prevent any future acts of international terrorism against the United States by such nations, organizations or persons”.)

[5] Ibid., Sections II, III and IV.

[6] Ibid.

A. The Poorly Constrained Commander-in-Chief

Both the U.S. constitution and the 1973 War Powers Resolution impose limitations on the use of force by the executive branch. But successive presidential administrations have aggressively interpreted these purported checks to the point that it is now far easier for the executive to unilaterally start or expand a war than it is for Congress to limit or end one. Although Article I of the constitution vests the power to declare war in Congress, and affords it numerous associated powers, Article II makes the president commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The executive branch has read the powers conferred by the commander-in-chief clause very broadly – to encompass prerogatives that go far beyond the self-defence powers it has always been understood to enjoy – and the constraints imposed by the War Powers Resolution very narrowly.

The U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), which is normally the last word on constitutional and statutory interpretation within the executive branch (and thus acts as something like an intra-branch Supreme Court), does acknowledge certain checks on the president’s unilateral war powers.[1] According to the framework OLC has developed since the Vietnam War, the president must be able to establish that a unilateral use of force serves a sufficiently important “national interest” and that the “nature, scope and duration” of the anticipated hostilities will not rise to the level of “war in the constitutional sense”.[2]

In many cases, however, neither of these tests poses a particular hindrance for the White House. Executive branch lawyers have deemed the national interest to include everything from an expansive conception of self-defence to stabilisation of regions far from U.S. shores, leading a growing chorus of experts to characterise this test as nearly meaningless.[3] For its part, the “nature, scope and duration” test is both pliant and unevenly applied by the executive branch. In the run-up to the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts, for example, OLC issued opinions positing that President George W. Bush had unilateral authority to launch those hugely consequential wars even in the absence of congressional authorisation.[4] These opinions remain on the books, despite the urging of scholars and former senior government lawyers from both parties that OLC withdraw them.[5]

[1] OLC’s legal guidance, usually recorded in written opinions, is treated as binding within the U.S. executive branch. Some, though not all, of these opinions are publicly released. The executive branch may withhold opinions on the basis of asserted classification or legal privilege.

[2] Stephen Pomper, “Targeted Killing and the Rule of Law: The Legal and Human Costs of 20 Years of U.S. Drone Strikes”, testimony to the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 2 February 2022; Memorandum for the Attorney General from Caroline D. Krass, Authority to Use Military Force in Libya, 2011.

[3] See, eg, Assistant Attorney General Steven Engel, “April 2018 Airstrikes against Syrian Chemical-Weapons Facilities”, U.S. Department of Justice, 31 May 2018; and Curtis Bradley and Jack Goldsmith, “OLC’s meaningless ‘national interests’ test for the legality of presidential uses of force”, Lawfare, 5 June 2018.

[4] For political reasons, the Bush administration did, in the end, secure explicit, separate authorisation from Congress for the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

[5] Pomper, “Targeted Killing and the Rule of Law”, op. cit.; Deputy Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel John Yoo, “The President’s Constitutional Authority to Conduct Military Operations Against Terrorists and Nations Supporting Them,” 25 September 2001; Assistant Attorney General for the Office of Legal Counsel Jay Bybee, “Authority of the President Under Domestic and International Law to Use Military Force Against Iraq,” 23 October 2002.

” The 1973 War Powers Resolution sought to strengthen lawmakers’ hand in matters of war and peace but in practice has proven a weak constraint on executive action. “

The 1973 War Powers Resolution sought to strengthen lawmakers’ hand in matters of war and peace but in practice has proven a weak constraint on executive action. Enacted toward the Vietnam War’s end as a safeguard against unilateral presidential war-making, the resolution both requires the executive to notify Congress within 48 hours of certain executive branch activities relating to military deployments and requires the U.S. military to withdraw forces introduced into “hostilities” (an undefined term) or situations where hostilities appear “imminent” if Congress has not authorised the deployment within 60 days of notification.[1] (These requirements are discussed at greater length in Section III below.) The resolution also provides that the two houses of Congress can together vote to direct the withdrawal of U.S. forces from hostilities through enactment of a concurrent resolution – ie, an act of Congress not requiring presidential signature.[2]

Yet a combination of executive branch interpretation, court decisions and congressional acquiescence have undermined the 1973 law’s effectiveness as a mechanism for regulating executive war-making. To be sure, the resolution still requires the withdrawal of unilateral troop deployments absent timely authorisation. But beginning early in the resolution’s history, successive administrations have interpreted the term “hostilities” very narrowly – taking advantage of the absence of statutory language that might otherwise have constrained it – and also developed counting methods that delay reaching the 60-day threshold.[3] Further, even under the executive branch’s own definition of “hostilities”, the 48-hour notifications mandated under the resolution have been uneven.[4]

Moreover, the Supreme Court’s 1983 INS v. Chadha decision cast constitutional doubt upon the capacity of Congress to order the withdrawal of troops through a concurrent resolution, as the War Powers Resolution originally contemplated.[5] Following the Court’s decision in Chadha, Congress amended the 1973 law to replace the concurrent resolution mechanism with procedures for a joint resolution that would require the president’s signature. Consequently, the president can start a war without congressional authorisation, but Congress cannot direct a withdrawal from hostilities unless 1) the president is prepared to sign off on it; or 2) it can muster the bicameral supermajority that is required to override a presidential veto. A congressional staffer described the notion that this latter mechanism could bring U.S. participation in a conflict to an end as “laughable”, given the practical and political obstacles.[6]

In theory, Congress has other options for stopping a war of which it disapproves. In particular, it can deny funding to a war already in progress. But Congress has only rarely deployed these tools.

Beyond the president’s constitutional powers, the executive branch has looked at the 2001 AUMF as affording it something close to a blank check for waging war on jihadist groups around the globe. On its face, the AUMF approves the use of force against groups the president determines to have “planned, authorised, committed or aided” the 9/11 attacks (as well as those who harboured such groups or persons), but successive administrations of both parties interpreted their way around the statutory language requiring a connection to those events. Through the executive branch’s interpretive gloss, groups can be unilaterally deemed targetable under the AUMF if they constitute “associated forces” of al-Qaeda because the U.S. executive views them as having entered the war alongside it.[7] Separately, in 2014, the executive branch also deemed ISIS to be targetable under the AUMF on the basis of historical ties between al-Qaeda head Osama bin Laden and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (the leader of ISIS’s predecessor entity al-Qaeda in Iraq), even though ISIS leaders had broken with al-Qaeda.[8]

[1] War Powers Resolution, Pub. L. No. 93-148, 87 Stat. 555 (1973) (codified at 50 U.S.C. §1547 (2018).

[2] Pomper, “Targeted Killing and the Rule of Law”, op. cit.

[3] Letter from Monroe Leigh, legal adviser to the Department of State, to Clement Zablocki, chairman of the House Subcommittee on International Security and Scientific Affairs, 3 June 1975; Todd Buchwald, “Anticipating the president’s way around the War Powers Resolution on Iran: Lessons of the 1980s tanker wars”, Just Security, June 28, 2019.

[4] See the website of the War Powers Reporting Project at the New York University School of Law’s Reiss Center on Law and Security. Brian Finucane, “Failure to warn: War powers reporting and the ‘war on terror’ in Africa”, Just Security, 4 October 2021; and “The War Powers Resolution: Concepts and Practice”, Congressional Research Service, 8 March 2019. The last source lists eighteen examples of apparent introduction of U.S. forces into hostilities or imminent hostilities from 1973-1998 not reported under the War Powers Resolution.

[5] INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983). The Supreme Court held the one-house legislative veto to be unconstitutional and cast doubt on the lawfulness of concurrent resolution mechanisms in laws such as the War Powers Resolution. Concurrent resolutions are passed by simple majorities in both houses of Congress but do not require presidential signature. Post-Chadha, there is a broad assumption that laws require bicameral support in Congress, presentation to the president, and either a presidential signature or (in the event of a presidential veto) an override by supermajorities in both houses.

[6] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff member, July 2021.

[7] Congress subsequently affirmed the president’s detention authority with respect to associated forces in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2012. Federal courts did so as well. See, for example, Ali v. Obama, 736 F.3d 542, 544 (D.C. Cir. 2013). “This Court has stated that the AUMF authorizes the President to detain enemy combatants, which includes (among others) individuals who are part of al-Qaeda, the Taliban or associated forces. As this Court has explained in prior cases, the President may also detain individuals who substantially support al-Qaeda, the Taliban, or associated forces in the war”.

[8] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit. The executive branch has not clarified how many of ISIS’s regional affiliates outside Syria and Iraq it deems covered by the AUMF.

B. Congressional Acquiescence and Inattention

Congress’s acquiescence in the diminution of its power in matters of war and peace, particularly over the last two decades, likely reflects the political incentives at play. According to current and former congressional staff, absent significant casualties or major military setbacks, most voters pay little attention to U.S. wars. Today’s armed forces are all-volunteer, meaning that many citizens do not know anyone, much less have a close family member, who serves. Meanwhile, the military’s heavy reliance on airpower, including drones, allows it to wage war while minimising the risk to U.S. servicemembers.[1] So long as U.S. men and women are not at risk, according to some congressional staff, matters pertaining to U.S. wars generally do not rank high among the issues that constituents raise with their elected representatives.[2]

[1] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, September 2021-January 2022.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, November 2021-January 2022.

” Members of Congress often see little political upside to taking a hard vote on the use of military force. “

As a result, members of Congress often see little political upside to taking a hard vote on the use of military force or appearing to be insufficiently supportive of deployed personnel. To the extent that Congress does take a position on issues relating to the use of force, it often does so quietly, enacting measures that in effect ratify actions the executive has already taken. Thus, members of Congress can reap the benefits of supporting U.S. troops without facing the scrutiny and accountability that would follow from an up-or-down vote to sanction a new front in the war on terror. For example, although Congress never passed an authorisation for the use of military force against ISIS (despite the Obama administration submitting such a draft authorisation to Congress in 2015), it has consistently appropriated funds for U.S. counter-ISIS operations in Iraq and Syria.[1]

These political dynamics are at play not only regarding authorisations for the use of force, but also with respect to oversight of how the executive branch is using it.[2] As discussed below, oversight can take many forms, but it often includes hearings, closed briefings, reporting requirements and other requests for information from the executive branch. Many members of Congress see little electoral advantage to be gained through war powers oversight and show considerable deference to the military, especially when it has been deployed to protect U.S. citizens from what has been portrayed as a global terrorist threat.[3] Members of whichever party is controlling the White House at the time are likely to see even less political benefit to exercising vigorous oversight.[4] Therefore, among the many issues competing for legislators’ time, scrutiny of the executive branch’s use of force is not usually a priority.[5]

Overlapping political and professional incentives may also shape the behaviour of congressional staff. Given the higher profile and greater proximity to power (not to mention, at least for senior jobs, higher pay) of positions in the executive branch, staff members of the president’s party may be reluctant to engage in aggressive scrutiny of the departments they oversee lest they harm their chances of being appointed to those very departments.[6]

Additionally, some former congressional staff and executive branch officials described what they referred to as the “capture” of staff by the counter-terrorism operating agencies they were tasked with overseeing.[7] One former official opined that there was a certain cachet in “being read into highly classified” programs and joining a small group of people rubbing shoulders with career counter-terrorism operators.[8] This former official compared the dynamic to the Hollywood film Almost Famous, in which an aspiring music journalist mistakenly “thinks he’s cool” by virtue of hanging around a rock band.[9] Current and former congressional staff as well as former U.S. officials characterised the staff of the House and Senate defence committees in particular as generally deferential to the Pentagon and typically unwilling to antagonise its officials.[10]

The converse is that when it does happen, oversight by members of Congress from the opposition party may be highly partisan and non-substantive – involving grandstanding rather than serious oversight. Even when members of Congress see advantage in trying to constrain the president’s use of force, such pushback often takes the form of performative soundbites rather than the sustained inquiry usually necessary to ferret out information from the executive branch.[11] The House of Representatives investigations of the 2012 attack on a U.S. facility in Benghazi, Libya, that cost the lives of four U.S. personnel, including then-Ambassador Chris Stevens, illustrate this dynamic. Rather than focusing on the Obama administration’s 2011 decision to intervene in Libya without congressional authorisation or the legal theories underpinning that choice, the Republican-dominated House conducted six separate inquiries – often tinged with conspiracy theory – for the admitted purpose of undermining the presidential candidacy of Hillary Clinton, who was secretary of state at the time of the attack.[12]

More recently, a combination of partisan bickering and distractedness undermined the effectiveness of a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing on the 2001 AUMF and war powers. The hearing had been due to focus on reforming the expansive and outdated authorisation for the war on terror. Since it was convened shortly after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, however, that subject predictably dominated the proceedings, with members of both parties using their question time to score political points as to which party had been more supportive of Ukraine and more belligerent toward Russia. As a consequence, the committee did not conduct coordinated questioning of the witnesses from the Departments of State and Defense. Members of Congress missed an opportunity to elicit more information from the Biden administration regarding its interpretation of the 2001 war authorisation and its proposals for reform.[13]

[1] Letter from the President – Authorization for the Use of United States Armed Forces in connection with the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, 11 February 2015. See also Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, November 2021-August 2022.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, September 2021-January 2022.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, former State Department official, September 2021-January 2022.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Crisis Group interviews, former congressional staff, November-December 2021.

[7] Crisis Group interviews, former congressional staff, former U.S. official, December 2021.

[8] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, December 2021.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, former State Department official, September 2021-January 2022.

[11] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff, August 2022.

[12] A Republican legislator involved in the inquiries, Kevin McCarthy of California, told a Fox News anchor that they were part of a “strategy to fight and win” in the 2016 presidential race. E.J. Dionne Jr., “Kevin McCarthy’s truthful gaffe on Benghazi”, The Washington Post, 30 September 2015.

[13] “The 2001 AUMF and War Powers: The Path Forward”, House Foreign Relations Committee, 2 March 2022.

” Members of Congress and their staff often have little incentive to do the hard work required to conduct effective oversight. “

As reflected in these episodes, due in part to the high tolerance of U.S. voters for interventions that do not directly involve U.S. troops (or, to the extent they do, have a light footprint) and that remain off the front pages, members of Congress and their staff often have little incentive to do the hard work required to conduct effective oversight.[1] At the same time, members have considerable latitude in their postures on these issues – even being able to reverse them without explanation – without suffering political costs.[2]

The lack of political saliency also affects the amount of time members of Congress are willing to spend on the war on terror. Time is a scarce resource for lawmakers, and several current and former congressional staff members cited tight schedules as a key constraint on scrutiny of the executive.[3] A range of policy issues and constituent service matters compete for lawmakers’ time, along with the ever present need to raise funds for re-election. If they are not hearing from their constituents about issues of war and peace, members of Congress are likely to direct their attention elsewhere.[4]

[1] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff, August 2022.

[2] For example, although he voted against authorising President Barack Obama to use force in Syria in 2013 in response to the regime’s use of chemical weapons, Senator Marco Rubio, a Republican from Florida, hailed President Trump’s retaliatory strikes against Syria four years later – operations undertaken without congressional authorisation.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, September 2021-January 2022.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, September 2021-January 2022.

III. The Information Gap

A. The Problem of Unreported Hostilities

Although Congressional inattention is one reason the legislature often fails to receive the information it needs to police the president’s use of force, the fault also lies with the executive branch, which has often taken a minimalist approach to meeting its legal reporting requirements. As noted above, Congress enacted the War Powers Resolution in 1973 to reassert its constitutional prerogatives with respect to war and peace. In doing so, it sought to forestall any president from taking the country to war without congressional awareness.[1] To this end, the Resolution’s Section 4(a) states that in the absence of a declaration of war or other statutory authorisation, the president is subject to tiered requirements to report to Congress on triggering actions by U.S. armed forces within 48 hours. In particular:

First, the president must report when U.S. military forces are introduced into 1) “hostilities”, a term that as noted the executive branch interprets narrowly, to include exchanges of fire with hostile forces and airstrikes; or 2) situations of imminent hostilities.[2]

Secondly, even if U.S. forces are not engaging in hostilities, the president must report the introduction of “combat-equipped” forces into a country (which the executive branch reads as forces carrying crew-served weapons such as mortars or machine guns requiring more than one person to operate).[3]

Thirdly, the president must report any substantial enlargement of such combat-equipped forces in a country where they are already present.[4]At first, the executive branch made commitments that it would adhere strictly to the Resolution’s reporting requirements. After the Resolution became law, the chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, Thomas Morgan, a Democrat from Pennsylvania, asked the secretary of state how the executive branch intended to follow it in practice, specifically the reporting requirements of Section 4.[5] In a 7 October 1974 letter, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger explained that “Secretary [of Defense James] Schlesinger and I have agreed that our respective legal counsels will be jointly responsible for bringing immediately to our attention cases where it would be appropriate for us to recommend to the President that a report be submitted to the Congress pursuant to Section 4 of the War Powers Resolution”. Kissinger elaborated that:[6]

[The] Office of the Secretary of Defense instituted an arrangement whereby the Legal Adviser to the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff [JCS] informs the Department of Defense [DOD] General Counsel of all troop deployment actions routed through the Chairman’s office which could raise a question as to whether a report to the Congress is required. In implementation of that arrangement a written instruction was promulgated establishing a War Powers Reporting System within the Operations Directorate of the JCS. Arrangements have been made for [the State] Department’s Legal Adviser to receive the same information as is supplied to the DOD General Counsel. Consultations between the two departments’ legal counsels will be arranged as needed. [1] Finucane, “Failure to warn”, op. cit.

[2] War Powers Resolution, op. cit. See also Letter from Monroe Leigh, legal adviser of the Department of State, to Clement Zablocki, 3 June 1975.

[3] Ibid.

[4] War Powers Resolution, op. cit.

[5] Letter from Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to Chairman Thomas E. Morgan, 7 October 1974.

[6] Ibid.

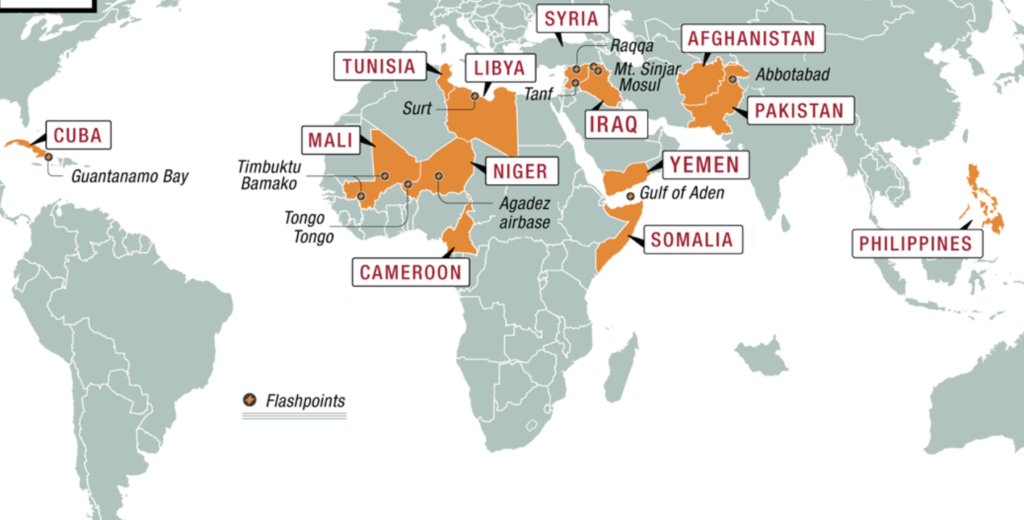

Yet, as Crisis Group has noted previously, since 2015, U.S. armed forces appear to have engaged in several incidents that, absent statutory authorisation, would seem to fall within the ambit of reportable hostilities for purposes of the War Powers Resolution.[1] Many of these hostilities involved fighting regional affiliates of al-Qaeda or ISIS, though not affiliates that the executive branch had previously announced to be within the scope of the 2001 AUMF. These missions have often involved “advise, assist and accompany” operations in which U.S. forces are ostensibly acting in a non-combat role to support local partners. Consider the following incidents, which took place during the tenures of three different presidential administrations.

Somalia, 2015-2016: Beginning in 2015, U.S. armed forces were reported to have engaged in ground combat with and conducted airstrikes on foot soldiers of Al-Shabaab, Somalia’s main Islamist insurgency.[2] (The executive branch had previously deemed some senior Al-Shabaab leaders to belong to al-Qaeda and thus targetable under the AUMF on that basis, but not the group as a whole.[3]) A Green Beret was awarded a Silver Star for his actions alongside Somali and Kenyan forces during one particularly intense firefight with Al-Shabaab in July 2015, including for “contributing to 173 enemy killed and 60 more wounded”.[4]

Mali, 2015: In November 2015, U.S. special operations forces participated in a battle with gunmen linked to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), to liberate hostages held in the Radisson Hotel in Mali’s capital Bamako.[5] Notably, U.S. forces engaged in this action despite the Pentagon having assured the Senate Armed Services Committee in 2013 that U.S. forces would not be involved in hostilities in Mali, merely providing non-combat support to France instead.[6] Not until the Trump administration’s time in office would the executive branch add AQIM to the scope of the 2001 AUMF.[7]

Tunisia, 2017: In February 2017, according to an award citation quoted by The New York Times, U.S. marines accompanying Tunisian partners “got into a fierce fight against members of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb” along the Tunisian-Algerian border.[8] A former U.S. official who confirmed the incident to Crisis Group described a marine being shot during the battle when a bullet ricocheted underneath his body armour. The official also noted that a U.S. intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance aircraft was overhead during the fighting.[9]

Cameroon, 2017: In a 2017 incident in northern Cameroon, U.S. Navy SEALs accompanied a Cameroonian partner force to a compound flying an ISIS flag. While the SEALs took up overwatch from some 300m away, the Cameroonian troops approached the compound, calling on its occupants to present themselves. An unidentified man emerged with an AK-47, and a Cameroonian soldier tried to fire upon him, but the soldier’s gun reportedly jammed. Acting in what a former official characterised as “collective self-defence” of the Cameroonian forces, a SEAL sniper shot and killed the man with the AK-47.[10]

Niger, October 2017: In the most notorious such combat incident (discussed in greater detail below), in October 2017, the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara killed four U.S. soldiers in an attack at Tongo Tongo, Niger, near the border with Mali.[11] The executive branch announced months after the fact that it had “concluded that this use of force was also conducted pursuant to the 2001 AUMF”.[12]

Niger, December 2017: A few months after the Tongo Tongo attack, U.S. forces engaged in what a former official described as a “big battle” with another ISIS affiliate, the Islamic State in West Africa Province (ISWAP), which is a splinter of Boko Haram.[13] Green Berets were accompanying Nigerien forces when they became involved in fighting in the Lake Chad region of south-eastern Niger.[14] Although U.S. forces were a few hundred metres back from the forward line of troops, they nonetheless engaged in combat, including by providing supporting mortar fire.[15] The Trump administration publicly reported the incident in cursory fashion in March 2018, and, after questioning by The New York Times, gave a brief statement on the episode.[16]

Mali, 2018: In 2018, according to Military Times, U.S. forces with a military observer group attached to the UN mission in Mali came under attack and several servicemembers were injured by jihadists in Timbuktu.[17] One of the U.S. personnel who survived the attack told the newspaper, “the severity [of the incident] was so, so played down”.[18]

Mali, 2022: Most recently, in January 2022, a U.S. soldier colocated with French forces at a base in the city of Gao was injured in a mortar attack that also killed a French soldier and wounded nine others.[19] The Pentagon did not identify which armed group conducted the attack.None of the above incidents was reported to Congress within the War Powers Resolution’s 48-hour reporting period (though similar ones in the same period were).[20] Nor was any of this fighting widely understood to be authorised at the time by the 2001 AUMF. In some cases, as with hostilities in Somalia and Niger, the executive branch subsequently invoked this war authorisation as legal authority which could obviate the need for such reports.[21] Yet, in other situations, the executive branch never offered a public explanation for the absence of reports to Congress under the War Powers Resolution.

There is a cost to avoidance of this nature. The War Powers Resolution was enacted in part to prevent any president from taking the country to war in secret. The failure to report such hostilities, or quietly and retroactively sweeping them under the 2001 AUMF, undermines this purpose, as well as the legislature’s capacity for oversight, and increases the risk that the U.S. will unwittingly slide into new conflicts without adequate deliberation of the costs and benefits of such action.

[1] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit. See also Finucane, “Failure to warn”, op. cit.

[2] Chad Garland, “Green Beret’s Silver Star sheds light on U.S. ground combat in Somalia”, Stars and Stripes, 7 July 2021; Paul McLeary, “Is there a new U.S. airstrike policy in East Africa?”, Foreign Policy, 24 July 2015.

[3] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.

[4] Garland, “Green Beret’s Silver Star sheds light on U.S. ground combat in Somalia”, op. cit.

[5] Kyle Rempfer, “Army special operator received valor award for actions concurrent with hostage crisis in Mali”, Army Times, 16 July 2019; “Marine of the year: Master Sgt. Jarad Stout”, Military Times, 12 July 2019.

[6] Letter to Senator Carl Levin from Robert Taylor, Acting General Counsel, U.S. Department of Defense, 6 May 2013.

[7] “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations”, U.S. National Security Council, March 2018.

[8] Lilia Blaise, Eric Schmitt and Carlotta Gall, “Why the U.S. and Tunisia keep their cooperation secret”, The New York Times, 2 March 2019.

[9] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, August 2021.

[10] Crisis Group interviews, former U.S. official, July-August 2021. Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.

[11] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, July 2021.

[12] “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations”, op. cit.

[13] Crisis Group interviews, former U.S. officials, July-August 2021.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations”, op. cit.; Charlie Savage, Eric Schmitt and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “U.S. kept silent about its role in another firefight in Niger,” The New York Times, 14 March 2018.

[17] Kyle Rempfer, “How U.S. troops survived a little known al-Qaeda raid in Mali two years ago”, Military Times, 16 April 2020.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Rachel Nostrant and Howard Altman, “U.S. service member injured, French soldier killed in Mali attack”, Military Times, 27 January 2022; John Vandiver, “Purple Heart awarded to U.S. special operations soldier wounded in attack in Africa”, Stars and Stripes, 12 April 2022.

[20] Finucane, “Failure to warn”, op. cit.

[21] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.; Finucane, “Failure to warn”, op. cit.

B. Uneven Transparency

In part because of the executive branch’s secretive gambits to avoid reporting and other requirements under the War Powers Resolution, Congress has consistently had to play catch-up in learning how and where the White House relies on the 2001 AUMF in waging the war on terror.[1] As noted above, the executive branch has, with congressional acquiescence and sometimes post hoc ratification, expanded the deemed scope of the authorisation over the past twenty years to include new groups and permit operations in new countries.[2] During much of this period, the executive branch has treated as secret the groups covered by the 2001 AUMF; prior to 2013, in fact, it did not even tell Congress with whom the U.S. was at war.[3]

In order to get a better handle on the war on terror’s scope, Congress has passed a number of additional reporting requirements.[4] These include one enacted in December 2019 that the president provide a comprehensive report every six months of activities undertaken under the 2001 AUMF.[5]

[1] “The Law of Armed Conflict, the Use of Military Force, and the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force”, hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, 16 May 2013. The committee chairman did not know which groups were covered by the 2001 AUMF, and the executive branch witnesses were unable when asked to share that information.

[2] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.

[3] Brian Finucane, “Putting AUMF repeal into context”, Just Security, 24 June 2021.

[4] 50 U.S.C. §1549; 50 U.S.C. §1550.

[5] 50 U.S.C. §1550.

” The Trump administration … the Biden administration … did not submit the legally required reports regarding actions taken under the 2001 AUMF. “

Yet the Trump administration and, at first, the Biden administration as well did not submit the legally required reports regarding actions taken under the 2001 AUMF. A congressional staff member attributed the Trump administration’s failure to do so to the general breakdown in relations between the White House and Congress following Trump’s first impeachment in 2019.[1] The Biden administration eventually submitted the report in March 2022, the day before a congressional hearing on 2001 AUMF at which witnesses from the Departments of State and Defense were to testify.[2] The hearing, as is not unusual, had the effect of spurring the executive branch to catch up on overdue tasks before senior officials were to testify. Although portions of these reports are unclassified, they have not yet been publicly released. Moreover, the Biden administration continues to treat as classified the full list of groups covered by the 2001 war authorisation.[3]

[1] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff member, September 2021.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, congressional staff members, September 2021-March 2022.

[3] “Unclassified Annex: Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks for the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations”, March 2022. See also Finucane, “Putting AUMF repeal into context”, op. cit.

C. Barriers to Information Flow Within Congress

On top of the challenges that Congress faces in obtaining information from the executive branch regarding the use of force, the legislative branch has itself erected several barriers that impede dissemination of information within Congress and thus hamper its own ability to monitor where, how and against whom the president is waging war. Congress ties its own hands through information silos, divisions between the staff of committees and personal offices, and the related bind of sharing classified information.[1]

Oversight of use-of-force operations is divided among three sets of committees in both the House and the Senate dealing with foreign affairs, armed services and intelligence. Each of these sets of committees has separate though overlapping oversight jurisdiction over the Departments of State and Defense, as well as the various U.S. intelligence agencies. According to several current and former congressional staff, information silos between these committees are a key reason that to “no one” in Congress has a comprehensive view of the use of force by the executive branch.[2] These silos are largely a function of committees guarding their bureaucratic turf, which too often leads them to hoard rather than share information. The executive branch is able to exploit this congressional tendency to avoid unwanted inquiries.[3]

A longstanding point of friction within Congress concerns which among the foreign affairs and defence committees has jurisdiction regarding the use of military force.[4] The foreign affairs committees (the House Foreign Affairs Committee and Senate Foreign Relations Committee) have jurisdiction over war authorisations, such as the 2001 AUMF. At least in principle, these committees should therefore have oversight of use-of-force operations under these authorisations.[5] In practice, however, the Senate and House Armed Services Committees regard most matters relating to military operations as lying within their exclusive purview.[6]

[1] For a general discussion of information silos, see Oona A. Hathaway, Tobias Kuehne, Randi Michel and Nicole Ng, “Congressional Oversight of Modern Warfare: History, Pathologies and Proposals for Reform”, William and Mary Law Review, vol. 63 (2021).

[2] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, July 2021-January 2022. See also Hathaway et al., “Congressional Oversight of Modern Warfare”, op. cit.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, July 2021-July 2022.

[4] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, July 2021-January 2022.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

” Jurisdictional disputes are particularly relevant to the oversight of “advise, assist and accompany” operations. “

These jurisdictional disputes are particularly relevant to the oversight of “advise, assist and accompany” operations. Although notionally non-combat, such operations nonetheless sometimes involve U.S. forces in hostilities. Such combat includes incidents such as those described above in which it is questionable whether Congress has authorised the use of force in the first place.

Some of these operations are undertaken in connection with a statute that permits the Pentagon to spend appropriated funds in support of foreign counter-terrorism forces. This statute is sometimes referred to as “127e”, a designation taken from its U.S. Code citation – 10 U.S.C. §127e. Though 127e is not a use-of-force authorisation (a position Congress explicitly wrote into the law following the attack at Tongo Tongo), U.S. forces have sometimes treated it that way in the field.[1] According to a former official, the military has used the authority to create “clear, unambiguous proxies of the United States”, which it could then partner with in combat operations.[2]

Notwithstanding the notionally non-combat purpose of the U.S. missions to advise, assist and accompany partner forces in conjunction with 127e programs, U.S. forces often found themselves using lethal force.[3] A former official suggested that the mission creep was inevitable, explaining that “if you’re accompanying a partner in combat, then you’re engaging in combat”.[4] A congressional staff member noted that one had “to assume [U.S. forces on 127e programs] engaged in occasional hostilities”, though Congress would often learn about such incidents only afterward, when U.S. troops were awarded medals or killed.[5] Although the executive branch does not publicly disclose where 127e programs operate, media reporting indicates U.S. forces deployed in connection with the authority have engaged in combat in several African countries.[6]

Disputes between the foreign relations and defence committees regarding oversight of these programs have contributed to inadequate supervision of these operations even within the executive branch. Due to concerns about the foreign affairs committees encroaching on their turf, the congressional defence committees have narrowly scoped the consultation requirements relating to use of this authority.[7] Although 127e requires the secretary of defense to obtain the concurrence of the relevant U.S. chief of mission to conduct a so-called 127e program in his or her area of responsibility, it does not require the concurrence or even notification of the secretary of state.[8] A legal requirement for the secretary of state’s concurrence is absent by design. According to current and former congressional staff, the defence committees fear that by involving the secretary of state in what they regard as an operational program, they would, in effect, commit themselves to sharing oversight jurisdiction over these programs with the foreign affairs committees, something they are loath to do.[9]

In the absence of a legal requirement to obtain the secretary of state’s concurrence, the coordination of these programs is left to the discretion of the relevant commander (eg, a four-star general responsible for U.S. operations in regions such as Africa or the Middle East) and the chief of mission for the pertinent country.[10] According to former U.S. officials, chiefs of mission in host countries were in their experience generally eager to support counter-terrorism operations and thus often easily persuaded by their military counterparts to concur in these programs without consulting the State Department in Washington.[11] Yet the lack of adequate consultation within the State Department could result in failure to fully consider legal, foreign policy and humanitarian concerns with such operations before approving them.[12] As a consequence, the executive branch may never have thoroughly contemplated – let alone vetted – decisions about whether and to what extent the U.S. should be involved in particular conflicts through such programs.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Crisis Group interviews, former U.S. officials, July-August 2021.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, July 2021.

[5] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff member, November 2021.

[6] Wesley Morgan, “Behind the secret U.S. war in Africa”, Politico, 2 July 2018.

[7] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, August 2021-January 2022.

[8] 10 U.S.C. §127e

[9] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, August 2021-January 2022.

[10] 10 U.S.C. §127e. In section 5703 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2022, Congress amended 127e to require that the “relevant chief of mission … inform and consult in a timely manner with relevant individuals at relevant missions or bureaus of the Department of State”. It left to the chief of mission’s discretion, however, who the “relevant” missions or bureaus at the State Department might be.

[11] Crisis Group interviews, former U.S. officials, July-August 2021.

[12] Ibid.

” Information silos between committees are by no means the only impediment to the flow of information within Congress. “

Information silos between committees are by no means the only impediment to the flow of information within Congress. Several current and former staff members interviewed by Crisis Group described divisions between committee staff and staff in individual congressional offices.[1] These two sets of staff answer to different bosses, with committee staff reporting to the chair and ranking members of the committee and staff in personal offices reporting to individual members.[2] Committee staff generally have better access to information from the executive branch. The relevant departments and agencies are often more responsive to the committee staff’s requests, and the chairs and ranking members are typically the recipients of congressional reports discussed above.[3]

Differential access to classified information further exacerbates the information asymmetry between committee staff and employees in personal offices.[4] Until recently, only committee staff have typically held clearances to view “Top Secret/Secure Compartmented Information” (TS/SCI).[5] As many classified reports and briefings are marked at this level, staff in personal offices have been denied access to them.[6] Recently, the Senate announced that one staff member from each personal office would be granted a TS/SCI clearance.[7] The House of Representatives has not announced whether it will follow suit.

These information asymmetries among staff can sometimes matter to policy outcomes because the policy agendas and preferences of these various principals may differ. For example, a committee chair might be more or less deferential to the military than an individual committee member.[8] But, in any case, personal office staff are handicapped in properly advising their bosses without full access to available information, particularly information restricted on the basis of classification.[9] Individual members may therefore be forced to rely upon committee staff, whose loyalties lie elsewhere, to brief and inform them.[10]

[1] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, August 2021-February 2022.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] See Mandy Smithberger and Daniel Schuman, “A Primer on Congressional Staff Clearances”, Project on Government Oversight, 7 February 2020.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Lexi Lonas, “Senators’ personal office staffers to get top security clearance: Report”, The Hill, 17 November 2021.

[8] Crisis Group interview, November 2021.

[9] Crisis Group interviews, current and former congressional staff, August 2021-February 2022.

[10] Ibid.

D. Case Study: Oversight Dysfunction and the Attack at Tongo Tongo, Niger

The killing of four U.S. soldiers by an ISIS affiliate at Tongo Tongo, Niger, in October 2017 and the startled reaction of many in Congress epitomises the dysfunctional oversight of use of force. In the attack’s aftermath, members of Congress said they were unaware that U.S. forces were engaged in hostilities in Niger or even present in the country at all.[1] Their surprise that U.S. forces were fighting jihadists in the Sahel resulted in part from the executive branch’s failure to report U.S. military operations to Congress. But members of Congress and their staff also failed to fully comprehend the information they did receive. The responses to the incident, including further obfuscation by the Trump administration, illustrate the ways that gaps in information and analysis can make effective congressional oversight in such settings so challenging.

As mentioned above, in the years leading up to the attack at Tongo Tongo, the executive branch repeatedly failed to report incidents in which U.S. armed forces in Africa engaged in hostilities with a range of jihadist groups. From at least 2015, U.S. forces often on ostensibly non-combat “advise, assist and accompany” missions in fact engaged in combat in Somalia, Mali, Tunisia and Cameroon.[2] Had the executive branch reported these prior hostilities to Congress, as would have been required under the War Powers Resolution absent expansive (and sometimes seemingly retroactive) readings of the AUMF, the Tongo Tongo attack might have come as less of a surprise.

Whatever the executive branch’s shortcomings in terms of sharing information with Congress, however, Congress also seems to have failed to fully understand the information that the executive branch did share with it.[3] In February 2013, the Obama administration notified Congress, consistent with the War Powers Resolution, that the Pentagon had dispatched combat-equipped forces to Niger to “provide support for intelligence collection and … facilitate intelligence sharing with French forces conducting operations in Mali, and with other partners in the region”.[4] In observance of semi-annual reporting requirements under the War Powers Resolution, the Obama and Trump administrations subsequently gave updates to Congress every June and December on the growing contingent of U.S. troops in Niger.[5]

Although these reports on combat-equipped troops did not detail what U.S. forces in Niger were doing, the armed services committees received additional information in closed briefings.[6] Yet the staff and members of these committees did not seem to grasp what “advise, assist and accompany” missions entailed.

[1] Valerie Volcovici, “U.S. senators seek answers on U.S. presence in Niger after ambush”, Reuters, 22 October 2017; Joshua Keating, “Tim Kaine on how Niger and Trump have stirred new anxieties about America’s forever war”, Slate, 1 November 2017; Joe Gould, “Did military hide the real mission of the Niger ambush from Congress”, Defense News, 8 May 2018.

[1] Keating, “Tim Kaine on how Niger and Trump have stirred new anxieties about America’s forever war”, op. cit.

[2] Crisis Group Report, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror, op. cit.; Finucane, “Failure to warn”, op. cit.

[3] Loren DeJonge Shulman, “Working Case Study: Congress’s Oversight of the Tongo Tongo, Niger Ambush”, Center for a New American Security, 15 October 2020; Alice Hunt Friend, “The accompany they keep: What Niger tells us about accompany missions, combat and operations other than war”, War on the Rocks, 11 May 2018.

[4] Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, 22 February 2013.

[5] See, eg, Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, 13 December 2013; Letter from the President to the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, 6 June 2017.

[6] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, July 2021.

” Congress was “naive” if it thought no one was going to get hurt on “advise, assist and accompany” missions. “

A former U.S. official who briefed staff members of the Senate Armed Services Committee in the wake of the attack was “stunned” that, after seventeen years of the war on terror, staff members did not understand what “by, with and through” – a phrase often used to describe U.S. partnered operations – meant in practice.[1] In this official’s view, Congress was “naive” if it thought no one was going to get hurt on “advise, assist and accompany” missions.[2] He attributed Congress’s failure to appreciate that U.S. forces were in combat on these operations partly to its inability to separate the “wheat from the chaff” in the information it received from the Pentagon.[3] Subsequent expressions of astonishment by members of the Senate Armed Services Committee attest to the failure of these closed-door briefings to illuminate the nature of U.S. operations in Niger.[4]

Another former official recounted a general failing of counter-terrorism oversight that could have contributed to Congress being blindsided by the attack at Tongo Tongo. This former official noted that while defence committee staff were generally attentive during counter-terrorism briefings, they asked few questions and lacked the necessary background “to drill down” for oversight.[5] Not surprisingly, briefers from the Pentagon would not volunteer information they preferred to keep close to the vest.[6] As a former congressional staff member observed regarding staffing levels and expertise, on “matters of life and death” there’s “not a level playing field” between Congress and the executive branch.[7] Another congressional staffer attributed the shock in Congress at the Tongo Tongo attack to a general lack of interest in African affairs on Capitol Hill.[8]

In the view of one former official, this absence of adequate supervision contributed to U.S. forces launching the fatal Tongo Tongo mission.[9] According to this official, the lack of effective oversight regarding “advise, assist and accompany” missions in Africa prior to the Tongo Tongo attack resulted in U.S. forces “running with scissors” – ie, undertaking overly risky activities, including conducting operations such as “chasing HVTs [high-value targets], which they never should have been doing”.[10]

Even after the attack, Congress struggled to get a straight answer from the executive branch about U.S. operations in Niger. The Trump administration provided shifting legal justifications. Then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis testified in October 2017 that U.S. forces were in Niger “under Title 10 in a train and advise role”.[11] (Title 10 is a chapter of the U.S. Code that includes Department of Defense authorities but is not itself a use-of-force authorisation.) In a subsequent report to Congress, however, the administration claimed that the 2001 AUMF covered both the October 2017 hostilities at Tongo Tongo and the “big battle” two months later in south-eastern Niger described above.[12] This justification was novel, as the executive branch had not previously invoked the 2001 war authorisation for Niger operations.

[1] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, July 2021.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Crisis Group interviews, former U.S. official, July-August 2021.

[4] Gould, “Did the military hide the real mission of the Niger ambush from Congress”, op. cit.

[5] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, December 2021.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Crisis Group interviews, former congressional staff, November 2021.

[8] Crisis Group interview, congressional staff member, July 2021.

[9] Crisis Group interview, former U.S. official, July 2021.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “The Authorizations for the Use of Military Force: Administration Perspective”, hearing before the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee, 30 October 2017.

[12] “Report on the Legal and Policy Frameworks Guiding the United States’ Use of Military Force and Related National Security Operations”, op. cit.

IV. Stonewalling

Beyond failing to report information to Congress, the executive branch sometimes affirmatively refuses to share documents relating to the use of force or related issues with Congress even when legislators specifically request them. Presidents of both parties regularly rely upon purported legal privileges as a tool to keep information from Congress, including its theories regarding the scope of its authority to use force either directly or indirectly through a partner or proxy. Yet understanding how the executive branch conceives of its own authority to wage war is vital if Congress is to review, constrain or shape such military operations.

A. Hiding Information behind Legal Privilege

The potential implications for international peace and stability of the executive branch’s undisclosed legal theories can be significant. In one notorious episode in 1989, William Barr, then head of OLC, refused to share with Congress a legal opinion regarding the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s authority to abduct people overseas on the grounds that the legal advice was confidential.[1] The legal opinion (eventually released to the public by a subsequent administration) concluded that the president could “override” the UN Charter’s prohibition on the use of force as a matter of U.S. domestic law.[2] As that prohibition is the key international law constraint on presidential war-making, the conclusion that the president can, in effect, disregard it is potentially of great consequence. In the short term, this opinion may have helped pave the way for the U.S. invasion of Panama in December 1989, an operation conducted without congressional authorisation to capture Panamanian leader Manuel Noriega.[3] It remains on the books.

Similarly, the Trump administration hid from Congress and the public a 2017 legal memorandum relating to the 6 April 2017 U.S. airstrikes on Syria in retaliation for the Syrian government’s use of chemical weapons. This memo was requested both by Senator Tim Kaine, a Democrat from Virginia who sits on both the Armed Services and Foreign Relations Committees, and separately under the Freedom of Information Act by the Protect Democracy Project, an advocacy organisation.[4] The Trump administration refused to divulge the document and in subsequent litigation with the Protect Democracy Project invoked the presidential communications privilege to justify withholding the memo from public disclosure.[5] The court ruled in favour of the Trump administration and the memo remains undisclosed.

The U.S. conducted a further round of retaliatory airstrikes on the Syrian government in 2018, following another chemical weapons attack. Although the Trump administration did eventually release a Justice Department opinion justifying the 2018 airstrikes as within the president’s authority under Article II of the Constitution, it is not publicly known to what extent this document mirrors the guidance from 2017.[6] Nor did the Trump administration ever publicly explain how these airstrikes against the Syrian government comported with international law, a subject of considerable international disagreement.[7]

[1] “FBI Authority to Seize Suspects Abroad,” hearing before a subcommittee of the House

Committee on the Judiciary, 1991. See also Ryan Goodman, “Barr’s playbook: He misled Congress when omitting parts of the Justice Dep’t memo in 1989”, Just Security, 15 April 2019.

[2] Assistant Attorney General William Barr, “Authority of the Federal Bureau of Investigations to Override International Law in Extraterritorial Law Enforcement Activities”, 21 June 1989.

[3] Goodman, “Barr’s playbook”, op. cit.

[4] Letter from Senator Tim Kaine to Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, 8 February 2018.

[5] Protect Democracy Project, Inc. v. U.S. Department of Defense, Memorandum Opinion, Case No. 17-cv-00842 (CRC) (D.D.C. 2018). This ruling holds that the government could lawfully withhold the legal opinions on the basis of presidential communications privilege.

[6] Assistant Attorney General Steven Engel, “April 2018 Airstrikes Against Syrian Chemical-Weapons Facilities”, 31 May 2018.

[7] Alonso Gurmendi Dunkelberg, Rebecca Ingber, Priya Pillai and Elvina Pothelet, “Mapping states’ reactions to the Syria strikes of April 2018”, Just Security, 22 April 2018. The Trump administration’s silence regarding the international law basis for U.S. strikes against Syria was not unprecedented. The Clinton administration, for example, declined to provide a legal justification (as opposed to a policy rationale) for the 1999 intervention in Kosovo.

” The executive branch has … cited interests in the confidentiality of legal advice to withhold information from Congress regarding indirect U.S. roles in conflict. “

The executive branch has also cited interests in the confidentiality of legal advice to withhold information from Congress regarding indirect U.S. roles in conflict, such as through arms transfers to foreign belligerents. Under the Arms Export Control Act (1976), Congress delegates to the president the authority to conduct weapons sales, but in principle retains for itself the power to demand information regarding proposed transfers or even block particular sales. (This latter power was also weakened by the Supreme Court’s above-referenced decision in Chadha.) In practice, however, the executive branch is able to shield relevant facts and analysis regarding U.S. arms sales from congressional scrutiny on the basis of poorly defined confidentiality interests.

With regard to the conflict in Yemen, the executive branch has repeatedly cited such vague confidentiality interests to withhold from Congress information pertaining to U.S. arms sales to and other support for Saudi Arabia that may have caused civilian casualties or law of war violations. Concerned about U.S. complicity, members of Congress have tried to look at U.S. involvement more closely, often to be frustrated by the executive branch. For example, Representative Ted Lieu, a Democrat from California, repeatedly asked the State Department to release a 2016 legal memorandum on U.S. military support for the Saudi-led coalition. According to The New York Times, this memo cited the risk that U.S. officials could be complicit in alleged law of war violations by virtue of that assistance.[1] The Trump administration rebuffed Lieu’s requests, on the stated basis of its “strong interest in maintaining the confidentiality of legal advice”.[2]

The Trump administration also relied on nebulously defined “executive privilege concerns” as part of a strategy for thwarting a congressionally requested investigation into U.S. arms sales to Saudi Arabia. In 2019, members of Congress asked the State Department’s Office of the Inspector General to look at the Trump administration’s decision to conclude certain arms sales to Saudi Arabia in the face of congressional opposition due to civilian casualties in the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen.[3] The inquiry also examined the State Department’s efforts to mitigate the risk that U.S. weapons transferred to Saudi Arabia would kill civilians in Yemen.[4]