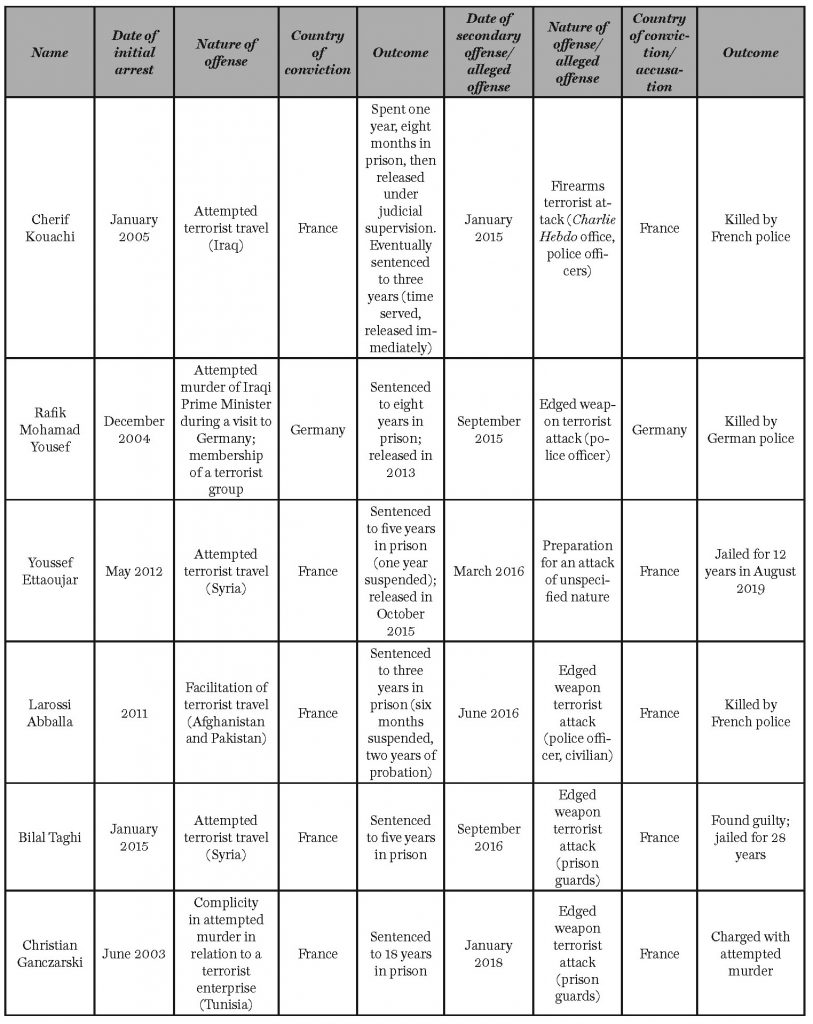

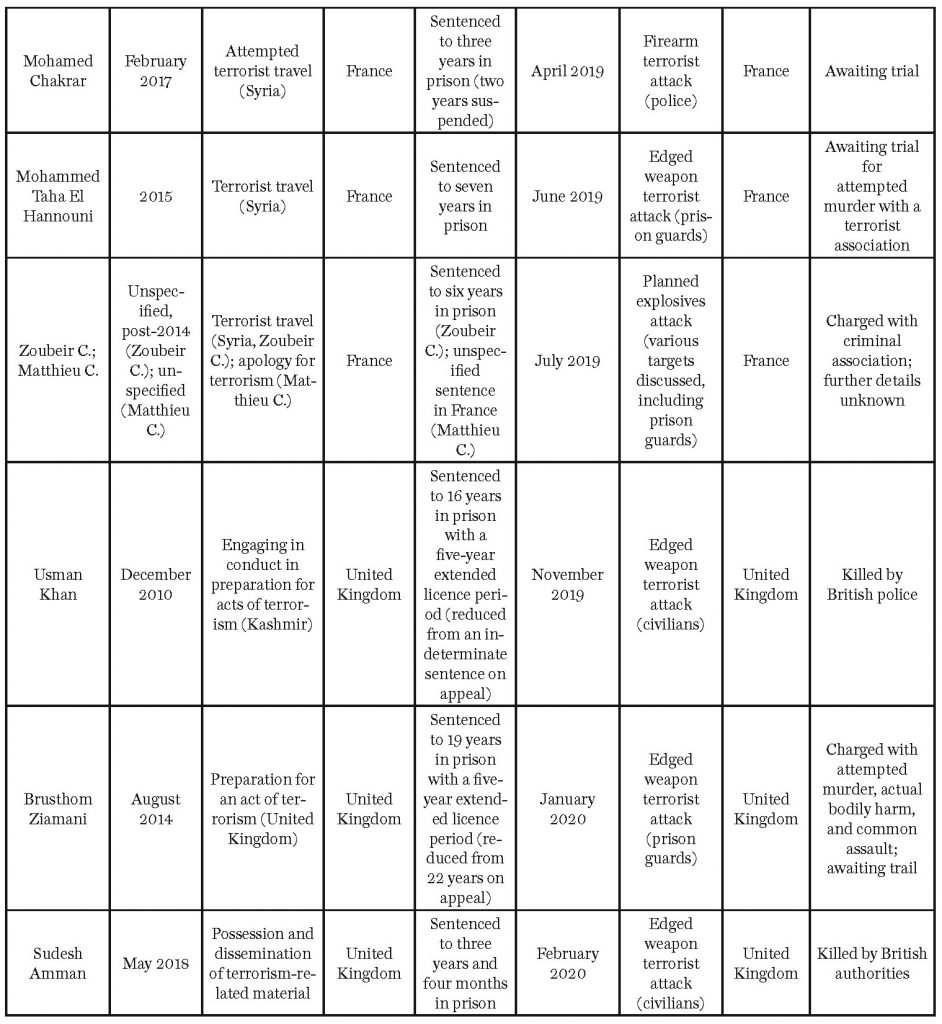

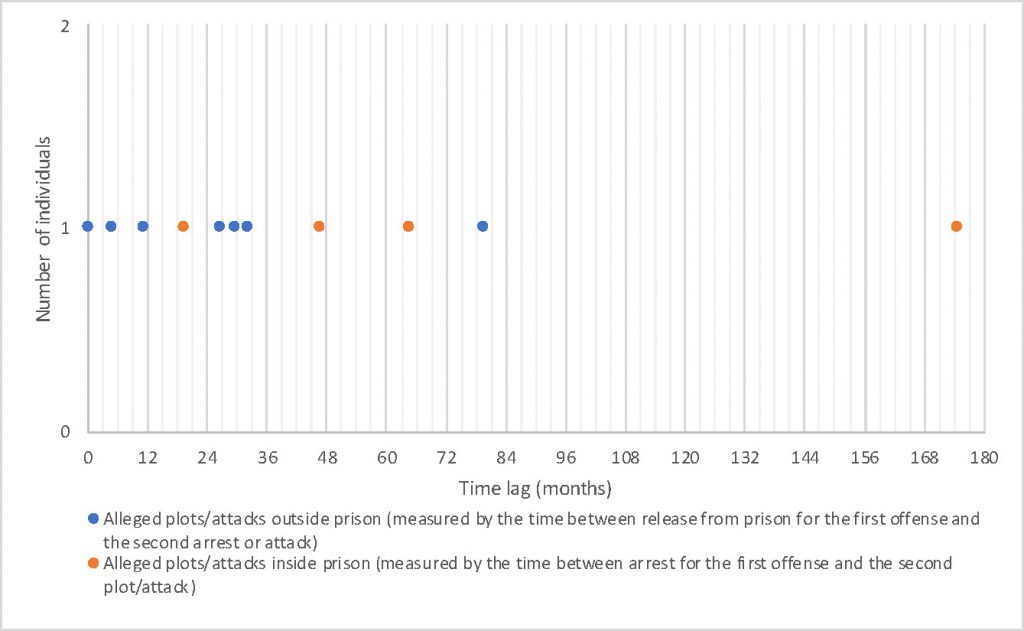

Two databases maintained by the authors shed light on the nature and scale of the threat posed by jihadi prisoners and prison leavers. Drawing from a database on terror activity in Europe, a new qualitative analysis of 12 alleged terrorist plots or attacks in Europe involving jihadi prisoners and prison leavers helps explain the nature of the threat, finding that both those thwarted in their attempts to participate in foreign terrorist fighting and those who returned from actually doing so were—from this limited sample—commonly involved in such attacks. This often manifested itself in specifically targeting the police or prison guards. There was no typical timeframe for terrorist reengagement or recidivism. Where the data was available, average time lag was three years, nine months and the median was two years, six months. A comprehensive second dataset of Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks in the United Kingdom between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2015 provides a quantitative case study into recidivism and reengagement. New calculations by the authors support recent findings pertaining to Belgium by Thomas Renard by finding terrorist recidivism among U.K. offenders who are convicted of multiple terrorism offenses on separate occasions is low. However, if individuals who had a prior criminal record for criminal behavior interpreted as extremism-related but not terrorism-related are included, the rate of recidivism posed by jihadi prisoners/prison leavers—and subsequent scale of the threat—is appreciably higher.

In December 2018, Gilles de Kerchove, the European Union’s Counter-Terrorism Coordinator, declared “prison leavers” to be the third-most serious threat Europe faced from Islamist terrorism. (Homegrown radicalization and returning foreign fighters were one and two, respectively.)1 Two incidents in the United Kingdom in recent months bore out de Kerchove’s concerns.

In November 2019, Usman Khan stabbed two people to death and injured three others during a terrorist attack in and outside Fishmonger’s Hall overlooking London Bridge in central London. Khan’s attack was disrupted by nearby civilians before he was shot and killed by the police. In February 2012, Khan had been convicted over a plan to travel to Kashmir to establish a training camp that would produce terrorists to carry out attacks there, with the possibility of returning to carry out future attacks in the United Kingdom. The broader cell he was part of—which was arrested in December 2010—had proposed attacking the London Stock Exchange.2

Then, in February 2020, Sudesh Amman stabbed two civilians in Streatham, south London, before being shot and killed by the authorities.a Amman had previously pleaded guilty in November 2018 to both possession and dissemination of terrorism-related documents.3

Similar incidents will inevitably arise in the future. According to a United Nations Security Council report, “{a}s many as 1,000 foreign terrorist fighters imprisoned on return to Europe prior to 2015 are expected to be released in Europe in 2020.”4 This figure does not even factor in those jailed across Europe for terrorism offenses not related to foreign fighting who will also be released this year. Furthermore, a July 2020 study by the Center for the Analysis of Terrorism (CAT) in Paris found that 60% of those who left France to fight jihad in Afghanistan, Bosnia, or Iraq between 1986 and 2011 went on to commit a fresh terrorist offense upon their return.5

Yet in a recent study on terrorist recidivismb in this publication, Thomas Renard stated that some of the public discourse on the threat was “overblown,” arguing that “Khan and Amman are more likely to be eye-catching outliers than a harbinger of things to come.” Renard’s analysis demonstrated that when looking at terrorist recidivism and reengagement statistics in Belgium between 1990-2019, less than 5% of convicted terrorists returned to terrorist activity. However, as Renard also acknowledged, “even a small number of recidivists can still constitute a most serious threat in the short- to longer-term.”6

This article seeks to broaden Renard’s assessment of the threat picture in Belgium.

In part one, it presents case studies from across Europe of individuals previously convicted of terrorism offenses who subsequently go on to plan or carry out a terrorist attack after a period of disengagement, typically imprisonment, both after and prior to release. The authors acknowledge that data for this section is not exhaustive. Therefore, part one of this study seeks to present a qualitative analysis on the nature of the terrorist threat posed by prisoners and prison leavers, not an overall sense of the scale.

The article uses open-source material to provide key details about the attacks or alleged plots, including where they took place geographically and whether they were committed by those who had left prison or those who were plotting while still incarcerated.

It then looks at the geographic scope of previous terror activity by the individuals included in this study as well as which of them had previous convictions pertaining to either foreign terrorist fighting or being ‘frustrated travelers’ who were unsuccessful in their attempts to access a conflict zone.

This analysis then explores the individuals’ trajectory of offense, examining whether their initial offense involved the intent of violence, as well as the timespan for reengagement between this initial offense and the actual alleged plot or attack.

It goes on to assess whether the individuals profiled in this study had declared an allegiance to a foreign terrorist organization; the extent to which—if at all—they were under surveillance by authorities at the time of their alleged plot or attack; and questions raised by the management of terror offenders, including the effectiveness of rehabilitation and reintegration efforts.

Part two of the article uses an additional, comprehensive dataset of Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks in the United Kingdom between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2015, which was previously compiled by one of the authors, to provide a quantitative, country-specific case study of the extent to which broader recidivism and reengagement by convicted terrorists is common. Therefore, this section is more concerned with the scale of the threat this cohort poses. The terrorist recidivism rate for all U.K.-based Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks during this timeframe is calculated. The article also provides an assessment of how those previously convicted of terrorist activity both in the United Kingdom and overseas, and terrorist offenses carried out by individuals with previous convictions interpreted as extremism-related, are relevant to the recidivism threat picture.

Part One: What 12 European Terror Cases Reveal about the Nature of the Prisoner Threat

This section provides qualitative data on 12 alleged jihadi terrorist plots/attacks that helps demonstrate the nature of the threat from jihadi prisoners and prison leavers in Europe.

Inclusion Criteria

This study analyses 12 alleged jihadi terrorist plots/attacksc that occurred in Western Europe between January 2014 and April 2020 in which at least one of the alleged plotters/attackers had been convicted in Europe of a previous terrorism-related offense.d This includes individuals killed during their attack as well as those convicted of—or awaiting trial for—planning an attack. These plots/attacks were extracted from a personal database of over 300 plots in Europe maintained by one of the authors.e

As the purpose of this database was to track the threat to Europe following the rise of the Islamic State, January 2014 was chosen as the starting point. Therefore, the database includes Islamist attacks that took place since that date; thwarted plots that led to convictions of those planning attacks in Europe; arrests of those suspected of planning attacks;f those assessed to be planning attacks who were subsequently deported on national security grounds; and a small number of incidents where a demonstrable Islamic State inspiration led to the targeting of different faiths, religious sects, and/or practices. To qualify for inclusion in this database, the violent act had to be focused on targets in Europe itself, as opposed to, for example, a plot targeting European embassies in the Middle East or Africa.

This database was compiled using open-source material. While the author attempted to be exhaustive, this data is unlikely to be so as there was neither the resources nor the language skills to monitor all terror cases across Europe. Furthermore, there will be cases where the sensitivity of how the intelligence was gathered means that terror suspects were never brought to trial and, subsequently, received no media coverage. Difficulties surrounding the categorization of violent incidents involving Islamists in prison may also mean there were incidents with potential terrorist intent that were not considered such by certain governments and therefore may be less likely to receive media attention. Therefore, this study is not exhaustive: there have potentially been more plots/attacks since 2014 involving individuals previously convicted of terrorism offenses.

While all individuals included in this study have planned, or allegedly planned, a distinct act of terrorist violence—either insideg or outside of prison—from January 2014 onward, the offense that led to that individual being incarcerated for the first offense occasionally occurred before 2014. The authors did not set a time limit regarding the date of the first offense, but the earliest arrest for terrorist activity among those profiled was 2003. The cut-off point for the second offense was April 30, 2020.

The study only looks at alleged jihadi terrorist plots/attacks involving individuals previously convicted in a civilian court in Europe of at least one terrorism related offense before being involved in a plot (alleged or otherwise) or attack in Western Europe. These criteria therefore excluded individuals convicted of a second terrorism offense that was not related to attack planning, for example, fundraising for terrorist purposes or possession of terrorist material. They also excluded the likes of Osamah Abed Mohammed, who was convicted in Zurich in March 2016 as part of an Islamic State-inspired Iraqi cell planning attacks in Switzerland.7 Mohammed was suspected of having previously been detained by U.S. forces in Iraq, after admitting to carrying out attacks on coalition forces.8 However, these suspicions were never tested in a European court.

The authors have chosen to focus, therefore, on a narrowly defined subset of terrorist reengagement. The cases are limited to planned or actual terrorist attacks involving Islamist extremists who had previously been convicted—and imprisoned—for a terrorism-related offense.

This approach led to a small sample size limited to 12 alleged plots/attacks. (See Table 1.) While this is a limitation to the study, it also enables a closer look at certain cases that have been of high concern to the security services and about which the press and the public have asked politicians what more could have been done to prevent their occurrence.

The Findings

The 12 alleged plots/attacks studied took place in three separate countries: France (eight cases), the United Kingdom (three cases), and Germany (one case).h Three attacks resulted in deaths (two attacks in France, one attack in the United Kingdom) and six attacks resulted in injuries (three attacks in France, two attacks in the United Kingdom, one attack in Germany). The remaining three plots were foiled, meaning there were no casualties.

Therefore, of the 12 alleged plots/attacks studied, there were victim casualties (either injuries or deaths) in nine incidents. In total, terrorists were responsible for 16 deaths and 28 injuries in these nine plots. The other three plots were thwarted by security services or the police.

While nine of 12 alleged plots/attacks leading to victims is a high percentage, as this study is not exhaustive, it should not be assumed that this is reflective of the overall likelihood that plots carried out by recidivists or those reengaging are likely to be successful.

Eight plots involved individuals who either acted alone or were arrested alongside others against whom charges were either dropped or charges of planning a specific act of terrorism in Europe were not pursued.i Four plots involved multiple perpetrators, some of whom had a prior (non-terrorist) criminal record.j

These 12 alleged plots/attacks involved 20 Europe-based individuals (i.e., the attacker, or an individual currently facing charges in relation to a plot). Of those, 13 had previously been convicted in Europe of terrorist activity. That meant there was only one alleged plot in the dataset in which individuals previously convicted of terrorism activity together.k

All 13 were male.

Prison Leavers

Seven alleged plots/attacks were committed by at least one individual who had been released from detention (four in France, two in the United Kingdom, one in Germany).l

The highest-casualty attack committed by those in this study was the attack on the Charlie Hebdo offices in January 2015, which led to 12 deaths and 11 injuries. One of the perpetrators, Cherif Kouachi, had previously been convicted of a terrorism-related offense in France.m Kouachi had been arrested in January 2005 as he prepared to leave the country and head to Iraq to take part in the fighting there.9 According to the French prosecutor in the case, Jean-Julien Xavier-Rolai, the ‘19th arrondissement cell’ that Kouachi was part of in Paris at the time had sent approximately a dozen individuals to Iraq to join up with Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the emir of al-Qa`ida in Iraq.10

While awaiting trial, Kouachi spent one year and eight months in prison and was then released under judicial supervision. When convicted at a 2008 trial, he was sentenced to three years but was immediately freed due to time served.11

Most prison leavers either carried out or planned to carry out their attacks alone. In the United Kingdom, Usman Khan and Sudesh Amman were examples of this. However, there were also prison leavers operating as part of broader cells with those not previously convicted of terrorism-related activity.

France saw the largest alleged cell involving an individual previously convicted in Europe for terrorist offenses. In April 2019, Mohamed Chakrar was arrested as part of a five-person cell alleged to be planning a firearms attack against the Élysée and against French police, specifically in Seine-Saint-Denis, Paris.12 Chakrar outlined his allegiance to the Islamic State while in custody and stated that he wished to die as a martyr.13

Previously, Chakrar had been just 15 years old when, in February 2017, he was arrested while attempting to travel to Syria.14 He told French investigators that his plan was to join the Free Syrian Army, fight against Bashar al-Assad’s regime, and undertake humanitarian work.15 However, many Western travelers to Syria at that stage were aspiring to live in Islamic State-controlled territory;n and a search of Chakrar’s iPhone revealed he possessed nasheeds calling for the death of non-Muslims, accessed jihadi Telegram channels, researched 9mm bullets, and possessed a video showing French police officers.16

As a result of this attempted travel, Chakrar was sentenced in 2017 to three years detention (two of which were suspended) and put on probation.17

The Threat Inside Prisons

Concerns about incarcerated terrorism offenders carrying out fresh acts of ideologically motivated violence deliberately targeting prison staff is increasingly relevant in Europe.

In August 2016, the Ministry of Justice in the United Kingdom published its findings of a review into “Islamist extremism in prisons, probation and youth justice.” Led by Ian Acheson, himself a former prison officer, one of Acheson’s key findings was “a more coordinated and rehearsed response to violent incidents” within prisons was required as “[s]ome prisoners sentenced under the Terrorism Act 2000 and its successors … aspire to acts of extreme violence which require not only action within prisons but oversight and direction from experienced operational staff working centrally.” The review went on to state that one of a variety of ways that Islamist extremism potentially manifested itself in prison was threats being made against staff.18

Acheson found this was not a problem distinct to the United Kingdom. Following visits to prisons in the Netherlands, France and Spain, the Ministry of Justice review emphasized the need for the “primacy of the police in resolving prison-based counter-terrorism incidents.”19

This study found four alleged plots/attacks (all resulting in actual violence) that occurred within prison by those previously convicted of terrorist activity and subsequently targeting prison staff (three in France, one in the United Kingdom).o Attacks inside prison by incarcerated terrorist convicts should not be assumed to be terrorist incidents, but as will be outlined below, all four attacks had an alleged or apparent terrorism dimension.p

The attacks perpetrated while in prison follow a familiar template: the construction and subsequent concealing of makeshift weapons used to stab prison employees (and, in one case, use of a fake suicide vest). In September 2016, for example, Bilal Taghi stabbed two supervisors at the Osny prison in France, where he was incarcerated, after he had sharpened the hinge of his cell window into a sharp object.20 Following the attack, Taghi said that he had intended to kill a representative of the French government in tribute to the Islamic State, making clear the terrorism dimension to the incident.21 He was sentenced to 28 years in prison for this attack.22 Taghi had been jailed the year before due to an unsuccessful attempt to travel to Syria to join the Islamic State.23

Similarly, Mohammed Taha El Hannouni allegedly used a piece of broken mirror and a table leg from his cell to injure two prison guards in June 2019. He was subsequently charged with “attempted assassinations on persons holding public authority in connection with a terrorist enterprise.”24 He was initially convicted for having gone to fight in Syria in 2014. Media reporting did not specify which group El Hannouni aligned himself with in Syria, instead reporting that he visited “jihadist fighting zones.”25

A slightly unusual case involved Christian Ganczarski, a former associate of Usama bin Ladin, who allegedly used a razor blade and either a chisel or pair of scissors (reports conflict) to injure three prison guards at Vendin-le-Vieil prison in northern France in January 2018.26 Ganczarski was a member of al-Qa`ida who was jailed for 18 years in France in February 2009 for “complicity in attempted murder in relation to a terrorist enterprise.”27 This pertained to his involvement in an April 2002 truck bombing of a synagogue in Tunisia that led to 21 deaths.28

Ganczarski was due for release in February 2018. However, he would then have become eligible for extradition to the United States where, in January 2018, he had been charged with “conspiracy to kill United States nationals, providing and conspiring to provide material support and resources to terrorists, and conspiring to provide material support and resources to al Qaeda.”29 Upon learning this, Ganczarski was recorded in a telephone call saying that he would take action to prevent his departure from France.30 His apparent ploy worked: following his alleged attack on the prison guards, Ganczarski remained in France, newly charged with “attempted assassinations on persons responsible for public authority in connection with a terrorist enterprise.”31

Finally, the most recent example occurred in the United Kingdom, in January 2020, when two prisoners at a Cambridgeshire prison injured four prison guards with ‘shank’ weapons they had constructed out of plastic and metal. Both men were wearing fake suicide vests at the time and were subsequently charged with attempted murder and assault.32 London Metropolitan Police stated they were treating the incident as a terrorist attack33 and one of the alleged perpetrators—Brusthom Ziamani—was serving a 19-year sentence after being found guilty in February 2015 of a plot to behead a British soldier.

Discussing his motivations for this earlier plot against a soldier, Ziamani said he was a supporter of the Islamic State and it was his “duty to help my brothers and sisters” in Syria. He said that “Because I have no means ov [sic] there I will wage war against the british [sic] government on this soil … this is ISIB Islamic State of Ireland and Britain.” Ziamani went on to state that “heads will be removed and burned…my fellow muslim brothers these people want war lets kill them slaughter them and implement sharia in our lands and UK [sic].”34

Plotting Inside Prison for a Terrorist Attack Outside of Prison

One nebulous plot in France, disrupted in July 2019, was allegedly planned from inside prison but was to be executed on the outside. In this case, the alleged protagonist was Matthieu C.,q a convert jailed for the offense of apology for terrorism—in other words, “presenting or commenting favourably on terrorist acts.”35 Matthieu C. had been housed at a variety of prisons, one of which was Châteaudun in northern France. There, he encountered Zoubeir C. (housed in the same prison but in a different building to Matthieu C.), jailed for six years for heading to Syria for six months in 2014, where he joined up with the then al-Qa`ida affiliate, Jabhat al-Nusra.36

Zoubeir C. was due to be imminently released, and Matthieu C. allegedly hoped he would commit a terrorist attack upon release. Matthieu C. allegedly attempted to pass messages to Zoubeir C. via another prisoner, including details of an individual on the outside who could provide him with weapons. Allegedly one of the potential targets discussed was prison wardens.37 However, the National Prison Intelligence Service (Bureau Central du Renseignement Pénitentiaire, or BCRP) had been monitoring Matthieu C. and bugged his cell. Both Zoubeir C. and Matthieu C. were subsequently charged with criminal association in July 2019.r

Geographic Scope of Previous Terror Activity

Of the 13 individuals studied in the 12 cases, only two individuals’ convictions for their first offense specifically pertained to planning specific acts of violence in the country in which they resided.

One was Brusthom Ziamani, who was convicted in the United Kingdom for having planned to kill a British solider.

The other was Rafik Mohamad Yousef in Germany. Yousef was part of a cell plotting to assassinate then Iraqi Prime Minister Ayad Allawi during a trip to Berlin in December 2004.38 After the plot was discovered, Yousef was jailed for eight years for membership in a terrorist group and attempted conspiracy to commit murder. (According to German authorities, the plot was insufficiently developed to charge Yousef’s cell with attempted murder.)39 He was freed in 2013 and, in September 2015, stabbed a police officer in Berlin before being shot and killed by a fellow member of the police.40 No terrorist group claimed responsibility for this attack.

Conversely, Christian Ganczarski was convicted in France for an attack that occurred in Tunisia; and though several of Usman Khan’s co-accused pleaded guilty to plotting a pipe-bomb attack inside the London Stock Exchange,41 his guilty plea specifically related to a plan to establish and recruit for a training camp on land owned by his family in Kashmir. The purpose of establishing the camp was to carry out terrorism acts, initially in Kashmir but with the possibility of returning to carry out attacks in the United Kingdom in the future.42

Frustrated Travelers and Foreign Fighters

Six individuals’ initial convictions for terrorist activity pertained to either their thwarted attempts to travel to a conflict zone in order to participate in foreign terrorist fighting; or successful travel to these conflict zones and subsequent participation in the fighting.

In 2011, Larossi Abballa was arrested for being part of a network facilitating jihadi travel from France to the Afghan/Pakistan border. In September 2013, Abballa was convicted in France of criminal association with a view to preparing terrorist acts. Abballa was sentenced to three years in prison (with six months suspended) and two years of probation.43 He was released immediately, having been on remand since 2011.44 In June 2016, Abballa stabbed a police officer to death at his property in the town of Magnanville, northwest of Paris, and then fatally slit the throat of the officer’s partner.45

Three individuals who were part of alleged plots/attacks had previously been thwarted in their attempts to take part in the fighting in Syria and one in Iraq (Cherif Kouachi, who had attempted to travel there in January 2005 46). Two individuals—Mohammed Taha El Hannouni47 and Zoubeir C.48—had successfully managed to travel to Syria (on both occasions from France), returned, and were subsequently convicted. Both allegedly planned or committed fresh acts of violence while in prison for this offense.

The Syrian jihad therefore played a prominent—but not ubiquitous—role in the trajectory of the jihadi attackers and plotters in Europe previously convicted there of terrorism-related offenses. Travel or attempted travel to Syria—between 2012 and 2017—formed the basis of the initial convictions for five of the 13 individuals involved in the 12 plots analyzed. It shows that there has already been some ‘blowback’ in Europe from frustrated travelers and foreign fighters.

Targets

Nine of the 12 alleged plots/attacks involved Islamist attacks upon security forces that succeeded in causing casualties.

As has been demonstrated, this manifested itself with ideologically motivated attacks on prison guards within the prison itself on four occasions (three times in France and once in the United Kingdom). Terrorist attacks on prison guards were also allegedly discussed in the alleged plot that was being formulated in prison but to be executed outside, involving Zoubeir C. and Matthieu C.49

Yet the police were also specifically targeted on three occasions outside of the prison setting: twice in France and once in Germany. Rafik Yousef stabbed a police officer in Germany; Larossi Abballa specifically targeted law enforcement in the Magnanville stabbings; and Mohamed Chakrar’s cell was suspected to be planning to target police officers for attack in a suburb of Paris.

There was an occasion where even though police were not the primary target of the plot, it still led to the death of an officer: during the Kouachi brothers’ attack on Charlie Hebdo, a police officer named Ahmed Merabet was murdered by the terrorists as he attempted to prevent their escape.50

Six of the nine plots that targeted police or security forces involved individuals who were known to have either been thwarted in their attempts to participate in foreign terrorist fighting; or had successfully managed to do so and subsequently returned to Europe. Four cases related to Syria (Chakrar, El Hannouni, Taghi, Zoubeir C.); one to Afghanistan (Ganczarski); while Cherif Kouachi was thwarted in his attempts to travel to Iraq but was likely able to later visit Yemen to receive training [see Allegiance to Foreign Terrorist Organizations section].

While the sample of cases in this study is small, it suggests that ‘blowback’ from foreign fighter travel among prisoners and prison leavers could commonly manifest itself in specifically targeting security figures: be it the police or prison guards.

This mirrors instructions given by the senior Islamic State terrorist Abu Mohammed al-Adnani in September 2014, who encouraged supporters to “[s]trike their police, security, and intelligence members, as well as their treacherous agents.”51 However, calls to target the police are not unique to the Islamic State: in the spring 2014 edition of al-Qa`ida’s English language magazine Inspire, the terror group told readers that, “US, UK and French police force are not used to a frontline-type war. They cannot withstand a bang of a grenade, let alone a full car bomb blast.”52

Trajectory

The initial offense committed (i.e., that which led to the first conviction) was generally less serious than the second offense (i.e., the alleged plot or attack).

However, the general trajectory should not be described as individuals moving from non-violence first to then allegedly plotting/committing a violent offense second. For almost all the 13 individuals, the first offense involved or allegedly involved the intent of violence in some way.

Furthermore, while, by definition, almost all terrorism offenses involve some kind of violent intent, nine of the 13 were involved cases with a very close proximity to violence. This manifested itself in actual attack planning (Ganczarksi, Yousef, Ziamani); an attempt to participate in foreign fighting (Chakrar, Ettaoujar, Kouachi, Taghi); or successful travel to participate in foreign fighting (El Hannouni, Zoubeir C.).

Three individuals were involved in cases where the proximity to violence was less pronounced: the facilitation of foreign fighting (Abballa); facilitation of training (Khan); and possession and dissemination of a document likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism (Amman).

There was only one individual for which the first conviction did not involve the intent of violence: Matthieu C., who had been jailed in France for crimes related to being an apologist for terrorism.

Timespan

The timespan for recidivism and reengagement was also calculated. For the alleged plots/attacks outside of prison, this was measured by the time between the date of release from prison for the first offense and the date of the second arrest or attack; and for the alleged plots/attacks carried out inside prison between the date of arrest for the first offense and the date of the second alleged plot/attack.s

For the 11 alleged plots/attacks for which data was available, the time lag between the first and second offenses ranged from 14 years, seven months (Christian Ganczarski) to 11 days (Sudesh Amman). The average time lag was three years, nine months and the median was two years, six months. The average time lag varied when calculated for the different types of alleged plots/attacks. For alleged plots/attacks outside of prison, the average time lag was two years, two months rising to six years, four months for alleged plots/attacks carried out inside prison. The spread for both types of alleged plots/attacks can be seen in Figure 1.

While such a small sample (n=11) should be treated with caution, it suggests that there is no typical pathway or timeframe for terrorist reengagement or recidivism. The findings differ from those in Renard’s study. From his dataset of jihadi terrorism convictions in Belgium between 1990 and 2019, Renard identified 27 cases of terrorist recidivism and (suspected) terrorist reengagement,t 17 of which information about the date of release from prison and the beginning of the second offense or engagement was available. Renard reported that the majority of these 17 individuals reoffended or reengaged within nine months, whereas the authors found that only two of the 11 alleged plots/attacks analyzed in this study saw reoffending within this timeframe. However, seven of the 11 alleged plot/attacks in the authors’ study saw reoffending within three years of the first offense. A further three occurred between an interval of three and seven years and one outlier (Christian Ganczarski’s attack on French prison guards) took many years for subsequent attack planning to come to fruition. It should be noted that unlike Renard’s Belgium study, the authors’ survey is not exhaustive, but the findings suggest that for Western Europe as a whole, most of the risk of terrorist recidivism or reengagement may occur within the first few years rather than months, particularly for alleged plots/attacks outside of prison. A comprehensive study of terrorist recidivism in Europe would shed more light on this question.

Moreover, Renard questioned whether some of those individuals in his dataset would have recidivated were it not for the Syrian jihad on the basis that most offenders had at least one offense, typically the second, relating to the conflict there.

The Syrian jihad played a significant role in the trajectory of the five individuals involved in the 12 plots analyzed in this study who were first convicted in relation to their attempted travel to Syria, suggesting that while the conflict may have acted as a pull for recidivism, it also served as an incubator for recidivist attack planning across Europe.

Allegiance to Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs)

The declaration of the Islamic State’s caliphate in June 2014 led to predictions of al-Qaida’s demise, as potential recruits and donors gravitated toward what for a number of years became the more powerful outfit.53 However, from the albeit limited dataset available, this was not entirely reflected with the offenders studied here. Instead, there is a mix of those loyal to the Islamic State, those loyal to al-Qaida or groups in its orbit, and those with whom there is a degree of ambiguity.

One perpetrator—Cherif Kouachi—explicitly acted on al-Qaida’s behalf despite the rise of the Islamic State. The Kouachi brothers were responsible for the Charlie Hebdo massacre. Al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) claimed responsibility for this attack.54

In January 2015, Yemeni officials told Reuters that Kouachi and his brother Said Kouachi headed to Yemen in 2011 to receive training from AQAP.55 u This was an assessment shared by French and U.S. officials speaking to The Wall Street Journal.56 Subsequent reporting has pinpointed this as being in the summer of that year.57

In the aftermath of their operation, Cherif Kouachi told French television (while on the run) that, “I was sent … by al Qaeda in Yemen … Sheikh Anwar al Awlaki financed my trip.”58 This is a reference to AQAP’s influential American Yemeni cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, who was killed in a U.S. drone strike in September 2011. Before his death, al-Awlaki directed several terrorist plots in the West, and between his death and a 2016 study for this publication, Scott Shane found evidence of the cleric’s influence in more than half of U.S. jihadi terrorism cases.59

There were also those who acted on the Islamic State’s behalf. This included Bilal Taghi, who stabbed two prison supervisors during his incarceration and explicitly stated that he wanted to target a symbol of the French state in tribute to the Islamic State.60

There was also one individual who had demonstrated at least some ideological alignment with al-Qaida previously but who then carried out an attack in the name of the Islamic State. Larossi Abballa possessed al-Qaida literature at the time of his 2011 arrest for facilitation of travel to Afghanistan61 and Pakistan.62 However, after murdering a police officer and his partner in Magnanville, Abballa broadcast a Facebook live video stating that he had sworn allegiance to then Islamic State emir, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi.63 He claimed to have pledged allegiance to al-Baghdadi three weeks prior to the attack taking place.64 The Islamic State subsequently claimed credit for the attack.65

News reports have outlined that Abballa was potentially tied to—and influenced by—Rachid Kassim,66 a French terrorist who used the caliphate as a base from which to direct a series of plots in France via social media.67 A month prior to Abballa’s attack, the Islamic State’s external operations chief, Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, had encouraged domestic attacks rather than travel to the caliphate. Al-Adnani stated that “the smallest act you do in their lands is more beloved to us than the biggest act done here; it is more effective for us and more harmful to them.”68 This may have resonated with Abballa, who seems to have already expressed some frustration prior to his first conviction that the efforts of his cell were being directed toward the jihad overseas rather than domestically. Abballa had texted another member of the cell, “Do you really think they need us over there (in Pakistan)? … Allah … will give us the means to raise the flag here.”69

While Abballa serves as an example of an individual whose first offense was more closely aligned with al-Qaida and his second offense tied to the Islamic State, this is not the only direction of travel. For example, it was reported in the U.K. press a month prior to the attack that he allegedly committed in prison, that Brusthom Ziamani had defected from a prison gang loyal to the Islamic State to one aligned with al-Qaida.70 (The reason why is unclear.)

There were also cases where the influence of one group over another was ambiguous. For example, Usman Khan’s November 2019 attack was claimed by the Islamic State.71 Indiscriminate stabbing is certainly a method favored by those loyal to the Islamic State. Furthermore, the network he was part of in the United Kingdom—the proscribed terrorist organization al-Muhajiroun (ALM)72—was known to have supplied fighters for the Islamic State in Syria.v The head of ALM, Anjem Choudary, was found guilty in July 2016 of “inviting support for a proscribed organisation” (specifically, the Islamic State).73

However, there is no evidence that has publicly emerged showing that Khan was in contact with the Islamic State, and unlike others who committed attacks in Europe, he had not arranged for a statement to be posthumously released declaring fealty with the Islamic State and its leadership.74 Furthermore, Khan’s 2012 conviction was as part of an al-Qaida-inspired cell, one where he had been recorded discussing bomb-making instructions that had been published in the al-Qaida English-language Inspire magazine.75

Ultimately, with perpetrators such as Khan, it is a challenging task to assess where al-Qa`ida’s influence ends and where the Islamic State’s influence begins.

Finally, in Germany, there was one attack with a link to Ansar al-Islam, a terrorist group based in northeast Iraq. Rafik Mohamad Yousef, who was involved in a potential plot to assassinate the Iraqi Prime Minister, was a member of Ansar al-Islam, a group that has had ties to both al-Qa`ida founder Usama bin Ladin and Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the founding father of the Islamic State.76

Surveillance

The imbalance between a growing terrorism threat and limited state resources is familiar to European security services. Shortly after the Charlie Hebdo attack, Andrew Parker, the then director-general of MI5, warned: “My sharpest concern … is the growing gap between the increasingly challenging threat and the decreasing availability of capabilities to address it.”77 Some of the cases analyzed here reflect that dilemma. In others, however, covert surveillance allowed the authorities to interdict planned attacks.

Cherif Kouachi was the only confirmed instance analyzed of a perpetrator reengaging without being still monitored in some way, by virtue of being in prison, on probation,w or under surveillance. Even this, however, was not down to ignorance about his potential threat. In fact, Kouachi’s surveillance had been stepped up after his brother returned from Yemen at the end of 2011, but with no evidence of new terrorism-related activity, it was discontinued in July 2014—six months before his attack—in favor of suspects deemed to be of higher risk.78 Both brothers were on the U.S. government’s central database of known or suspected international terrorists, as well as a smaller “no fly” list barring them from boarding flights to or in the United States.79

Several of the plots involving prior terror offenders were thwarted by covert surveillance.

Having been released from prison in October 2015 after trying to reach Syria (a crime for which he was sentenced to five years, with one suspended), Youssef Ettaoujar was put under house arrest as part of the French state of emergency and was closely monitored by the Directorate General of Internal Security (DGSI) for a month before his arrest in March 2016.80 Ettaoujar was eventually jailed for 12 years for planning a firearms attack on an unspecified target in France.81

Ettaoujar’s previous conviction related to when he and an associate, Salah-Eddine Gourmat, tried to travel to Syria in 2012. This unsuccessful attempt led Ettaoujar to be jailed for five years, with one year suspended. In March 2014, Gourmat made another attempt—this time successful—to travel to Syria. French authorities suspected Ettaoujar and Gourmat remained in contact once the latter had made it to the caliphate. Gourmat was eventually killed in a drone strike in Raqqa in December 2016.82

Teenage alleged Islamic State supporter Mohamed Chakrar was arrested in April 2019 in an educational center in Seine-Saint-Denis, Paris, where he had been detained on probation following his sentencing in January 2019 for attempted terrorist travel to Syria two years beforehand when he was aged 15. The cell he was allegedly part of had been under surveillance by the DSGI since February 1, 2019.83 Three of his alleged accomplices were arrested in Paris on the same day as Chakrar after two of them were reportedly observed repurposing Kalashnikovs they had acquired as part of their alleged foiled plan to attack the Élysée and French police.84 A police source reported a lack of supervision at Chakrar’s educational center and he was alleged to have met up with his accomplices in person on several occasions.85 Chakrar was also reportedly friends with a fifth accomplice, arrested in Strasbourg 11 days later for his alleged planned role broadcasting a video of allegiance to the Islamic State on behalf of the cell.86

There were also those for whom surveillance or electronic monitoring did not prevent an attack. In Germany, Rafik Mohamad Yousef removed an electronic ankle-monitoring device on the day he stabbed a police officer who had been called to a district in Berlin after members of the public reported that a man with a knife was acting aggressively and threatening passers-by in the area.87 Sudesh Amman was another example. Having been released automatically from prison in the United Kingdom—where his behavior had already caused concern—he was placed under full surveillance. Within days the officials monitoring Amman were ordered to be armed. The following week, they shot him dead as he began stabbing passers-by on a London High Street with a knife he stole in a shop.88

It is not clear whether Magnanville attacker Larossi Abballa was still under surveillance at the time of his fatal stabbing of a French police commander and his partner in June 2016. Having been convicted in 2013 of aiding a group that had been recruiting fighters for jihad in Pakistan, Abballa was released owing to time spent in jail awaiting trial and was placed under surveillance until November 2015. He was later placed under phone surveillance as part of an investigation that began in February 2016 into a group believed to be traveling to Syria, with police sources stating that while the evidence collected suggested he was radicalized, it had not indicated that he was preparing to carry out an attack.89 However, it is unclear whether this investigation had been completed by the time of his attack and therefore it is unclear whether he remained under surveillance.x

The Management of Terrorism Offenders

The cases of alleged plots/attacks inside prisons illustrate recurrent policy questions in Europe on the management of terrorism offenders. Brusthom Ziamani and Mohammed Taha El Hannouni were each separately able to mount attacks on prison guards from within the mainstream population, in the latter case prompting calls from French prison unions for radicalized prisoners to be moved to “specialised establishments.”90 Bilal Taghi’s attack on prison officers, by contrast, occurred on a dedicated counter extremism wing that was piloting the segregation of offenders who were known to be radicalized but who were also assessed to not present the highest security risk.91 Christian Ganczarski’s alleged attack on guards in a French high security prison occurred while he was in isolation ahead of his (now delayed) extradition to the U.S.92

They also raise difficult questions about the effectiveness of efforts to rehabilitate and reintegrate ideologically motivated offenders. London Bridge attacker Usman Khan was monitored by MI5 after he left prison, although not under the same level of day-to-day scrutiny as Amman.93 He was in central London to attend a conference on rehabilitation organized by Learning Together, an educational initiative that brought students from Cambridge University together with current and former prisoners to discuss criminal justice. Khan had previously worked with the group and appeared in their promotional literature as a case study to show how they helped rehabilitate terrorists.94

Following Khan’s attack, the psychologist who helped design the United Kingdom’s deradicalization programs acknowledged: “[W]e have to be very careful about ever saying that somebody no longer presents a risk of committing an offence. I don’t think you can ever be sure.”95

Part Two: What U.K. Data Reveals about the Scale of the Prisoner Threat

This section expands upon a comprehensive dataset of Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks in the United Kingdom between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2015 to provide a quantitative study of the extent to which broader recidivism and reengagement by convicted terrorists is common in that country. It provides the terrorist recidivism rate for all U.K.-based Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks during this timeframe. Whereas part one of this study was more focused on the nature of the threat, part two uses a country-specific case study in an attempt to explore the scale.

Inclusion Criteria

Instances of convicted terrorists reengaging in the form of a planned or attempted attack—as narrowly defined by the authors—are uncommon. The database on which part one of this study is drawn contained only 12 incidents of individuals previously convicted of terrorism-related offenses who went on to allegedly plan or carry out a terrorist attack either after or prior to release from prison. One important caveat: the purpose of the database was to track the threat to Europe following the rise of the Islamic State rather than a study on terrorist recidivism, and so while attempts were made to be as exhaustive as possible, there have potentially been further examples of plots/attacks involving individuals previously convicted of terrorism offenses.

However, data previously collected by one of the authors suggests that broader recidivism and reengagement is complex and that there are overlapping areas between terrorist recidivism narrowly conceived as two distinct convictions for terrorist activity and broader crime-terrorism recidivism, understood as including individuals who are convicted on two separate occasions for at least one terrorist offense during one of those convictions. This section draws on a comprehensive dataset of 269 Islamist terrorism convictions and attacks in the United Kingdom between the beginning of 1998 and the end of 2015 that was produced for the U.K. Home Office and published by the Henry Jackson Society in 2017.96 Cases were identified through open-source material including news and legal archives and monitoring police and Crown Prosecution Service statements and social media, as well as court records and indictments that were obtained on request.y

Between 1998 and 2015, there were 10 cases of individuals who, at the time of arrest for the second (and, in one case, third) U.K. terrorist offense, had already been convicted of a terrorist offense in the United Kingdom within this timeframe. An increased policy focus on jihadi prisoners and prison leavers led the author to calculate and publish here for the first time the terrorist recidivism rate in the U.K. dataset: 3.7%. Here, terrorist recidivism is understood as individuals who are convicted on two separate occasions for at least one terrorist offense each time.

This terrorist recidivism rate is low, especially compared to recidivism generally. It also falls within the range of terrorist recidivism rates from 12 terrorism studies between 2004 and 2020 compiled by Renard for his study for this publication, which ranged from 0% in a number of studies (including Marc Sageman’s study of 172 jihadis in 2004) to 8.3% in a 2013 study in Indonesia.

None of the 10 cases in the author’s U.K. study, however, involved attack planning, with the perpetrators typically favoring fundraising for terrorist purposes, or inciting murder. Six of these 10 cases involved members of the proscribed U.K.-based terrorist group al-Muhajiroun.97

The author identified a further three cases of individuals who, at the time of their arrest for the U.K.-based terrorist offense that warranted their inclusion in the dataset, had previously been convicted of terrorist activity overseas. These cases involved two individuals convicted in absentia in 2003 and 2011 for alleged bomb attacks in Morocco and Bahrain, respectively, and an individual convicted of an illegal border crossing in Indian-controlled Kashmir while allegedly fighting with the Kashmiri separatist group Harakat-ul-Mujahideen.z Including these cases, which are questionable owing to the lack of judicial independence in these countries, would raise the terrorist recidivism rate to 4.8%, which coincidentally is also the figure for terrorist recidivism and suspected reengagement calculated in Renard’s Belgium study.aa This new statistic demonstrates that solely looking at domestic terrorist convictions can only provide an insight into part of the overall problem.

The author identified a further 12 U.K. terrorist offenses within this timeframe (beginning of 1998 to end of 2015) that had been committed by individuals who had a prior criminal record for non-terrorism activities that the author of the dataset interpreted as containing an extremism-related motivation or element. These were typically for public disorder (such as harassment and threatening behavior) or low-level criminal damage, often in relation to public al-Muhajiroun activism or other extreme networks.

Three of these 12 cases were planned or attempted attacks in the United Kingdom.ab In the three cases, the prior convictions had been for minor (albeit suspected extremism-related) public order offenses.

The first case was Waheed Mahmood, who was jailed for his role in an al-Qa`ida-directed 2004 fertilizer bomb plot. During the trial, Mahmood’s Islamist convictions were reported by the media, including that during the 1990s he had attended radical political meetings in Crawley and Luton and that, in 1993, he had received a conditional discharge for using “threatening, abusive or insulting words during a Muslim demonstration.”98

The second case was Shah Rahman,ac who was convicted alongside London Bridge attacker Usman Khan in 2012. During sentencing, the judge stated that while the cell was under surveillance Rahman had drawn attention to himself by being arrested for a “minor, jihadist inspired, public order offence” in London.99

The third case was Michael Adebolajo, who was jailed for killing Fusilier Lee Rigby in 2013. Adebolajo had assaulted a police officer during an al-Muhajiorun solidarity rally for a terrorism suspect in 2006.100

These combined 25 cases—of terrorist offenses being committed by individuals with previous convictions for terrorist activities or what the author interpreted as extremism-related activities —account for 9.3% of U.K. terrorism convictions between 1998 and 2015. The authors acknowledge that categorizing criminal behavior as extremism-related is a fine judgment, but nonetheless consider it a useful area for further research.

A further 44 terrorist offenses were carried out by individuals with previous convictions that did not include terrorist activities or behavior that the author interpreted as extremism-related. These were for a variety of offenses, notably public disorder, theft, assault, drug-related, and possession of offensive weapons or firearms. Taken together, therefore, one in six (16.4%) U.K. terrorist offenses between 1998 and 2015 was committed by an individual with a prior, non-extremism or terrorism-related criminal record.

The relationship between terrorism and criminality is an increasing area of focus in academia. Furthermore, it encapsulates the fears of many Western policymakers over the nature and scale of radicalization in prisons, particularly when this involves a criminal offender being reconvicted for a terrorism-related offense. Data on current prisoners assessed as radicalized illustrates the potential scale of the problem. In the United Kingdom, there are 238 people in custody for terrorism-related offenses,101 however, up to 800 prisoners are managed by a counterterrorism specialist case management process at any one time.102 In France, as of the end of 2018, 500 detainees convicted of terrorism charges were in prison, with a further 1,200 reported to have been radicalized.103 Approximately 90% of those 1,700 people will be released by 2025.

Conclusion

After studying decades’ worth of data in Belgium, Thomas Renard’s study contended that the threat posed by terrorism recidivists to Europe may be exaggerated. Using the United Kingdom as a reference point, this study supports Renard’s finding of a low rate when assessing recidivism among U.K. offenders convicted of multiple terrorism offenses on separate occasions within the United Kingdom itself.

However, when other factors are considered—individuals who at the time of their arrest for the U.K.-based terrorist offense had previously been convicted of terrorist activity overseas; and terrorist offenses carried out by individuals with previous convictions that the author interpreted as extremism-related—the rate grows appreciably.

Furthermore, as an increased number of individuals who supported the Islamic State are released across Europe, this may lead to an increase in recidivism and reengagement. After all, what applied to jihadis’ conflicts of the past may not hold in the era of the caliphate. As Aimen Dean, a former member of al-Qa`ida who became a spy for British intelligence, has written, “I look back in to my time in Bosnia and the Philippines, even my first visit to Afghanistan, as almost innocent expeditions in pursuit of an ideal” in contrast to the gruesome brutality of modern jihadi conflicts.104

The precise nature of the threat posed by those soon due for release having previously committed a previous terrorism offense will only become clear in the months and years ahead. Yet, as Renard acknowledges, it is unlikely that the problem set posed by ‘prison leavers’ will disappear entirely. The internal threat to prisons posed by radicalized prisoners will also likely endure. Governments will need to be able to mitigate both trajectories simultaneously.

While much of this study has focused on attack planning, it is also important for policy makers to broaden their horizons beyond acts of violence. Convicted terrorists who use their gravitas and credibility to recruit others to the Islamist cause—inside or outside of prison—are clearly still a national security concern, even if they are not breaking the law or planning a fresh attack themselves.