Key points

- After 12 years of civil war, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s government has consolidated its power and defeated credible threats to its rule. The anti-Assad armed opposition, which once controlled half of Syria, is relegated to the northwestern province of Idlib.

- While the Biden administration recognizes that Assad will likely remain in office, U.S. policy remains punitive, maintaining comprehensive sanctions on Syria until Assad negotiates political reforms with his opponents and agrees to free and fair elections.

- This policy will not produce the desired results. Assad is firmly entrenched, benefits from the help of security partners in Iran and Russia, who prefer that he stays in power, and remains highly unlikely to comply with U.S. demands. The status quo amounts to collective punishment of the Syrian population.

- Approximately 900 U.S. troops remain in eastern Syria, allegedly to train and advise the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces against ISIS. But ISIS lost its territorial caliphate more than four years ago. The risk of keeping U.S. forces there in perpetuity which includes sporadic attacks on U.S. positions and escalation risks with various actors, outweighs any rewards.

- Neither the sanctions nor the occupation of eastern Syria serves U.S. security interests. The former does no good, and the latter risks embroiling the United States in a mission without an end date.

- The United States should withdraw its remaining forces and offload what is left of the counter-ISIS mission to local actors. The United States should also reduce if not end its failing sanctions regime.

The Syrian Civil War and the evolution of U.S. policy

U.S. interests in the Middle East are limited: defend against anti-U.S. terrorist threats, prevent long-term disruptions to the flow of oil in the international market, and ensure no power can dominate the region.1 The United States has adopted a risky, resource-intensive strategy to accomplish these objectives, with U.S. Central Command stationing between 40,000 and 60,000 troops across a constellation of bases in the region.2 But defending U.S. interests does not require a permanent military presence. Scattered terrorist organizations that might target the United States are best handled by local authorities and, if necessary, long-range U.S. strikes, not permanent troops.3 Moreover, no single power in the Middle East is economically or militarily strong enough to reach hegemonic status, even if it wanted to; the major powers balance each other and are currently seeking a détente. Russia and China have exhibited no interest in policing the Middle East’s territorial disputes and sectarian squabbles.4 Even if the United States—which is now the world’s leading oil producer—had to worry about disruptions in the Middle East’s oil supply causing price increases, it is unlikely that a long-term U.S. troop presence would prevent such disruptions.5

Even if these flawed rationales for the U.S. presence in the region made sense, they would not justify current U.S. policy in Syria. Concerns about oil and hegemony do not apply in the case of Syria, which in pre-war times was a minor oil producer: Its 2.3 billion barrels comprise only 0.1 percent of the world’s total reserves.6 The Syrian state was too poor and weak to affect the Middle East’s balance of power in a significant way before the war and is even weaker today after more than a decade of internal conflict. U.S. interests in Syria are in fact extremely narrow, centering on preventing the Islamic State from launching attacks against the United States. Imposing sanctions on Syria to force a change of government and occupying a portion of Syria in perpetuity are not required to achieve that goal.

The last three U.S. administrations, however, have unsuccessfully pursued more ambitious goals like the transformation of Syria’s political system. The Obama administration authorized a CIA-backed program (Operation Timber Sycamore) to arm and train the anti-Assad insurgency in 2013 and publicly announced that it would provide limited military aid to the anti-Assad insurgency that same year.7 Both programs produced meager results. Jihadist factions within the broader insurgency emerged as the most powerful and effective fighting forces on the ground, leading some veteran Middle East hands, like former National Security Council Director Philip H. Gordon, to worry about a jihadist explosion in post-Assad Syria.8 Some of the supplies donated by the United States to vetted rebel groups were stolen by fighters affiliated with Al-Qaeda while some of them were sold on the black market.9

While President Donald Trump formally abolished the CIA’s program in 2017, his administration nevertheless viewed Syria as an extension of its maximum pressure strategy on Iran.10 U.S. policy rested on five goals: (1) an enduring defeat of ISIS; (2) the resolution of the Syrian conflict through a UN political process; (3) diminished Iranian influence; (4) the safe return of refugees; and (5) a Syria free of weapons of mass destruction.11 In September 2018, National Security Adviser John Bolton expanded those goals, telling the Associated Press that U.S. troops would remain in Syria unless all Iranian forces and Iranian proxies left the country—a declaration that, if taken seriously, made a long-term U.S. presence virtually inevitable.12 Ambassador James Jeffrey, Trump’s special envoy to Syria, added a sixth objective to the list: turn Russia’s military presence in Syria into “a quagmire.”13

The Trump administration left office having accomplished none of these goals. The “enduring defeat” of ISIS—effectively killing every single militant under the ISIS umbrella—proved unrealistic.14 Syria’s conflict has subsided due to Assad’s battlefield success, not U.N.-facilitated diplomacy, which remains stalled.15 Iran continues to hold significant influence in Syria, with Iranian-linked militias occasionally shelling U.S. forces.16 Some of those same militias have been incorporated into the Syrian security forces.17 With a poor economic future and concerns about personal safety, few refugees are willing to return.18 Assad also retains a small chemical weapons capability and continues to obstruct investigations by the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons.19

The Biden administration narrowed those objectives somewhat upon entering office in January 2021.20 The United States is now concentrating on easing Syria’s humanitarian crisis, holding Assad accountable for war crimes, defeating ISIS, and maintaining existing ceasefire arrangements between the Syrian army and its armed opponents.21 Facilitating talks between the Syrian government and the Syrian opposition has been outsourced to the United Nations and countries with a bigger stake in the war’s outcome, such as Turkey, Iran, and Russia.22

U.S. policy in Syria continues to rely heavily on economic pressure. The 2019 Caesar Syrian Civilian Protection (Caesar) Act is a prominent example of this. Rather than targeting specific individuals or sectors of the Syrian economy, Caesar sanctions target all areas under Syrian government control, where the majority of Syrians now live.23 Any foreign person who “provides significant financial, material, or technological support to, or knowingly engages in a significant transaction with” the Syrian government (or any entity owned or controlled by the Syrian government) will no longer be able to do business in the United States or access the U.S. financial system.24 The sanctions aim to complicate Assad’s ability to govern and prevent post-war reconstruction in government-held territory until the U.S. president observes that Syria has adopted significant policy changes, such as releasing all political prisoners, holding members of its own government accountable for war crimes, ending aid cutoffs in opposition-held areas, and ensuring the safe return of Syrian refugees.25

In practical terms, the United States is offering foreign entities a choice: you can either do business with the world’s largest economy or you can do business with the Syrian government. The Biden administration is adamant that the United States will only reconcile with the Syrian government after a “Syrian-led and Syrian-owned” political transition process occurs in line with UN Security Council 2254, which calls for the establishment of a national unity government, intra-Syrian negotiations on a new constitution, and free elections under UN supervision.26 U.S. officials have reiterated this message to their Arab partners as well, opposing any normalization efforts with Damascus.27 Despite this uncompromising approach, Assad remains in power and views his opponents as terrorists, not opponents with legitimate grievances.

The United States also continues to prosecute a military campaign against the remnants of ISIS in eastern Syria. That campaign began in September 2014, when the United States, with the support of Arab partners, first used air power to target ISIS checkpoints, training compounds, and command posts.28 In September 2014, Congress authorized the training and arming of vetted Syrian opposition forces for the purpose of reclaiming land controlled by ISIS.29 In November 2015, U.S. special operations forces deployed to Syria to aid the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).30 The U.S. troop presence in the country reached a reported high of 2,000 in December 2017.31 The Biden administration has largely continued its predecessors’ counter-ISIS policy, even as ISIS has ceased to exist.32 The United States maintains roughly 900 U.S. troops across multiple locations, including the al-Tanf garrison, where U.S. forces administer a 55-kilometer deconfliction zone to ensure hostile actors (Russian mercenaries, Syrian troops, and pro-government militias) do not threaten operations there. According to U.S. Central Command, in 2023 the U.S. military has conducted 90 operations against ISIS in Syria, 87 with the SDF and 3 of them unilaterally.33

Current U.S. policy is outdated and hurts the Syrian people

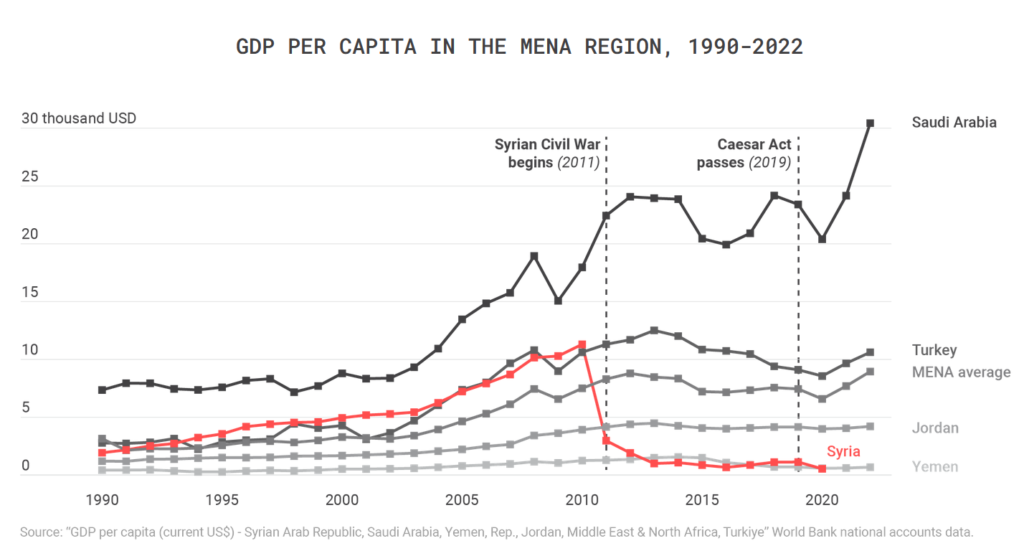

Syria is a wreck. After over a decade of civil and proxy war, Syria’s economy is in shambles relative to its neighbors. The World Bank classified Syria as a low-income country in 2018. The only other country in the Middle East with such a ranking is Yemen. 34 In 2010, Syria’s economy was more than nine times larger than Jordan’s. By 2020, Syria’s GDP was less than a quarter of Jordan’s.35

Ravaged by a destructive civil conflict, Syria’s economy is one of the worst in the Middle East. However, U.S. sanctions have also dissuaded third parties from investing in Syria’s reconstruction or providing humanitarian assistance.

Syria’s healthcare system remains dilapidated: 45 percent of its public health centers are not fully functioning; shortages of medicine afflict Syrians across the country; and almost 65 percent of Syrian households interviewed by the International Rescue Committee reported difficulty accessing health services.36 Meanwhile, estimates of Syria’s reconstruction costs range from $250 billion to more than $400 billion.

Despite recent demonstrations in the south over poor living conditions and high fuel prices, the Syrian government’s hold on power seems quite firm. The anti-Assad armed opposition has lost many of its external patrons, including Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and Jordan, all of which have reached cooperation agreements with Damascus in recent years. The Syrian political opposition has been and remains riven by personality disputes and ideological differences; it also lacks influence on the ground.37 The Assad government, in partnership with Russia and Iran, vanquished the insurgency on the battlefield using tactics such as indiscriminate air attacks and aid cutoffs in opposition-controlled areas until fighters agreed to lay down their arms and evacuate to Idlib.38 And while the Kurdish-led SDF east of the Euphrates River remains a strong fighting force that proved its mettle during the years-long military campaign against ISIS, it is not interested in fighting Assad. In fact, it is seeking to negotiate with him.39

Arguments for U.S.-Syria policy reform

Reforming U.S.-Syria policy is long overdue for four specific reasons. First, Syria’s neighbors have come to terms with Assad’s political survival and have calculated that bringing him back into the region’s politics holds more promise in meeting their respective interests than isolating him does.40 Second, U.S. sanctions hurt the Syrian people more than their leaders. Third, sanctions historically have rarely compelled targeted states to dramatically change their conduct. Finally, a persistent U.S. military presence in Syria is unnecessary for U.S. counterterrorism goals and involves unjustified risks and costs based on our security needs.

The Arab world has moved on, making an isolation campaign less feasible

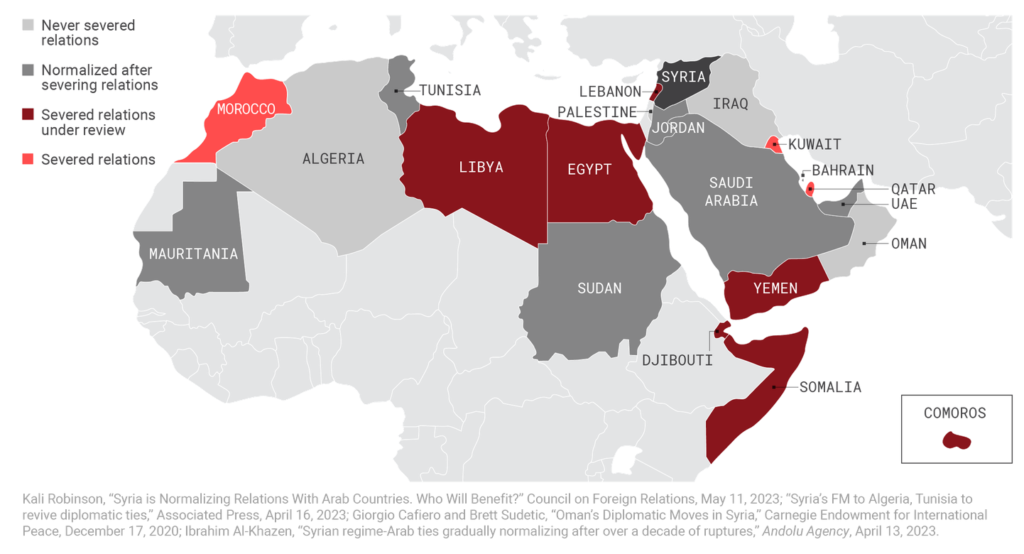

The same powers in the Middle East that once armed, financed, and trained the anti-Assad insurgency have now reconciled themselves to the reality of Assad’s staying power.41 There has long been a sentiment in the region that the status quo of isolation simply is not working, as Saudi Foreign Minister Faisal bin Farhan admitted in February 2023.42 This is the result of a years-long process. The UAE re-opened its embassy in Damascus in December 2018 and has hosted Assad twice for in-person meetings on strengthening bilateral relations.43 Abdullah II, the king of Jordan and the first Arab leader to call on Assad to step down, is now trying to work with Damascus to combat the smuggling of narcotics. Syrian-Saudi relations were normalized in April 2023, with the two countries resuming direct flights and consular services.44 A month later, Syria was re-inducted into the Arab League after a suspension that lasted nearly twelve years.45

In short, the Middle East has moved on from trying to oust or reform the Assad regime and is instead living with the political reality of Assad’s rule. The United States’ policy is the opposite: insensitive to changed circumstances and detached from achievable objectives. U.S. partners in the region recognize the United States’ inflexibility and are trying to work around U.S. restrictions. Three weeks after Secretary Blinken reiterated U.S. policy against normalization, Jordan aligned with the majority of states in the Arab League to support Syria’s readmission into the organization as a full member.46

This should not be surprising. Individual Arab states have their own reasons for normalizing relations with Damascus. As stated above, Jordan is primarily concerned with stemming the flow of Captagon, a deadly amphetamine that is produced in Syria and transported through Jordanian territory on its way to the Gulf Arab states (allegations of Syrian government involvement in the manufacturing and smuggling of the drug have been documented by researchers).47 For the UAE, improving ties with Syria means retaining at least some influence in a country that Iran, Russia, Turkey, and the United States have carved into respective spheres of influence.48 Turkey, long Assad’s staunchest adversary, hopes that a comprehensive reconciliation with Damascus will allow Turkey to deport some of the four million Syrian refugees that Ankara hosts back to Syria. Persistent U.S. disapproval of these regional developments is futile and puts the United States on the opposite side of a concerted push by regional powers to move past deeply rooted grievances in pursuit of de-escalation. Arab normalization with Assad also undermines U.S. attempts to isolate the Syrian government, further reducing the already unlikely prospect of Syrian political reform. No campaign of isolation against Assad is likely to succeed if Syria’s neighbors refuse to buy into it.

Syria’s normalization with the Arab League

U.S. sanctions primarily punish Syrians, not Assad

The U.S. sanctions regime against Syria is predicated on the idea that sufficient pressure will cause Assad to give in and comply with U.S. demands. This assumption was always questionable; even when the fighting came within miles of the presidential palace, Assad demonstrated no willingness to compromise with his political opponents. Today, such a development is extremely unlikely given the facts. The Syrian government is in its strongest military position since the civil war began. The Syrian army and pro-government militias control approximately 70 percent of the country’s territory, with most major cities, transportation arteries, airports, and ports in Assad’s hands.49

If the United Sates’ Syria policy was effective in isolating Assad and reforming Syria’s government, it might be seen as a brutal but useful tradeoff for Syria’s well-being over the long term. But after more than a decade of an ever-tightening sanctions regime, U.S. policy has immiserated ordinary Syrians and done little to foster a political transition. While the Syrian government is primarily responsible for the devastation wreaked on Syria’s infrastructure, economy, and healthcare system, U.S. sanctions on the Syrian economy have aggravated the poor conditions the Syrian people face on a daily basis. More than fifteen million people, or 70 percent of Syria’s population, need humanitarian assistance to survive.50 Twelve million people are considered food insecure and more than thirteen million have fled their homes during the course of the conflict, including more than six million refugees.51 Nine out of ten Syrians live below the poverty line, the result of a depreciating Syrian currency and rising food prices.52

The United States has tried to rectify the situation by committing nearly $17 billion in humanitarian assistance since the beginning of the war.53 Even so, humanitarian aid is designed as a stop-gap measure on the road to full economic recovery. U.S. sanctions, however, prevent this recovery from happening. The United States is well within its rights to not participate in Syria’s reconstruction. But the scope and depth of the U.S. sanctions regime, principally the Caesar Act, deters other states from doing the same. Few regional powers will move to rebuild Syria or invest there under threat of U.S. financial penalties. Consequently, the Syrian people remain trapped between a predatory government and U.S.-imposed economic restrictions that keep the country in a desultory state.

The U.S. Treasury Department states that U.S. sanctions do not apply to humanitarian activities, and several general licenses have been issued to permit the use of U.S. banking channels to process transactions related to a variety of not-for-profit activities in Syria in the fields of agriculture, public health, civil society, and education.54 The United States broadened these exceptions after a devastating earthquake in February 2023, authorizing a 180-day carve-out of its Syria sanctions program to ensure humanitarian relief efforts were not obstructed.55

Humanitarian waivers are good in theory but often do not work in practice. Financial institutions, conservative in interpreting U.S. law and policy guidance, are wary of actions that could result in U.S. fines, prosecution, or reputational damage.56 U.S. banks are not alone in this respect; according to the European Parliamentary Research Service, European Union (EU) sanctions on Syria have had a “chilling effect” on European financial institutions that would otherwise be open to Syria-related transactions.57 A similar phenomenon was documented by UN special rapporteur Dr. Alena Douhan during a November 2022 trip to Syria. She found that medicines and medical devices exempted from sanctions are nevertheless difficult to come by for the Syrian people due to a fear among suppliers, exporters, and banks of possible legal exposure.”58

The Syrian people, not the Syrian government, are bearing the burden of the U.S. sanctions regime. Assad continues to ensure his core constituencies in the Syrian military and the Alawite community, as well as his extended family, are given ample opportunity to get rich.59 Informal criminal networks have been established to help recoup some of the losses in Syria’s formal economy.60 Regular Syrians have no such recourse.

Sanctions rarely lead to major policy change

Sanctions have a bad track record of coercing targeted states to compromise on their core interests.61 Because sanctions tend to demand that states sacrifice something they deem important, states under sanctions usually choose to live with, and adapt to, the economic pain rather than concede to foreign pressure. Nationalism can motivate a state’s willingness to resist foreign diktats, particularly if the only other alternative is capitulation.62

Syria is not the only example of economic coercion failing to produce the desired results. Cuba maintains its authoritarian-style government and an independent, adversarial foreign policy despite a six-decade-long U.S. trade embargo. The Trump administration’s maximum pressure strategy on Iran, which sought to push Tehran into negotiating a new nuclear agreement and conceding on major elements of its foreign policy, instead compelled the Iranian government to escalate the very actions the United States objected to.63 U.S. financial sanctions on Venezuela’s oil industry, the source of almost all of its export earnings, failed to coerce Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro into resigning—if anything, the sanctions aided him by providing an opportunity to blame the United States for Venezuela’s economic crisis and denounce the U.S.-supported political opposition.64 Maduro’s actions are no surprise to scholars who have found that comprehensive sanctions can limit personal liberties and political space in targeted states.65

The case in Syria is no different. Assad’s core priorities are to stay in power and strengthen the political system that his father, Hafez al-Assad, built over a span of three decades. U.S. policy threatened both of those priorities, which meant Assad had ample reason to resist no matter how much economic pain the United States brought to bear.66

Assad also had the benefit of having partners invested in his survival, which helped nullify the impact of U.S. sanctions. For Iran, Syria under the Assad family has been a critical asset in a region largely skeptical, if not hostile, to Iranian power. As for Russia, the ouster of Assad could potentially have jeopardized its security relationship with Syria, which dates back to the 1950s, as well as its port facility in Tartus abetting the eastern Mediterranean. Russian President Vladimir Putin viewed Assad as a bulwark against a jihadist takeover and was concerned about the Syrian government’s collapse affecting security in the Caucasus, Central Asia, and Russia proper.67 Iran and Russia have therefore kept Assad afloat because it was in their interest to do so. Support continues to this day; a network of Shia militia factions organized by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) remains entrenched in Syria, backfilling the regular Syrian security forces.68 Russia still conducts occasional airstrikes in support of the Syrian military and offers low-interest loans to Syria to purchase food and other products manufactured by Russian companies.

All of these factors weigh heavily against the effectiveness of U.S. sanctions. Assad has deftly exploited U.S. sanctions to bolster his power, even as economic pain trickles down to ordinary Syrians.

Open-ended military missions distract and weaken the U.S.

U.S. policymakers justify the U.S. military presence in eastern Syria in a number of ways. Some argue that a continuous troop presence provides the United States with leverage over Assad, whose desire to reclaim the SDF-controlled oil fields in the east may convince him to be more flexible on political reform.69 Others maintain that a U.S. troop presence is necessary to deter Turkey from launching a large-scale attack on Kurdish positions—Joe Biden seemed to suggest as much during his 2020 presidential campaign.70 Still others argue that U.S. troops are vital for keeping the tens of thousands of ISIS fighters, family members, and sympathizers under detention.71

None of these justifications hold up to scrutiny. ISIS today has nowhere near the strength, manpower, and wealth it had at its height in 2014 when the group controlled a swath of Iraq and Syria the size of the United Kingdom and governed around eight million people. The ISIS territorial caliphate was destroyed in May 2019 when the last stretch of land in the Syrian town of Baghouz was captured by U.S.-backed Kurdish fighters. Because ISIS no longer controls territory, it cannot tax the population. Without a reliable stream of income, it must rely on kidnapping and smuggling.72 Multiple senior ISIS commanders, leaders, and facilitators have been killed in decapitation strikes, and ISIS has been forced to decentralize operations due to constant military pressure from multiple quarters.73 ISIS’s ability to plan, resource, and execute attacks against the United States was always inflated; the group’s propaganda reach was greater than its capacity for action. To the extent ISIS was involved in terrorist operations against the United States, its role was indirect; for example, the 2016 nightclub shooting in Florida that killed 50 people was not an ISIS operation per se but rather a lone-wolf attack perpetrated by an ISIS sympathizer.74 Maintaining a long-term U.S. ground presence in eastern Syria does nothing to prevent these types of lone-wolf attacks.

At present, ISIS attacks are limited to low-level, unsophisticated strikes on targets of opportunity such as convoys and checkpoints. The SDF has become increasingly competent in finding and neutralizing ISIS cells in their area of responsibility and is capable of executing independent operations.75 The U.S. Director of National Intelligence’s 2023 Worldwide Threat Assessment stated that “In Iraq and Syria, ISIS has slowed its operational tempo relative to when it controlled physical territory from 2014–[20]19, probably because of logistical, financial, personnel, and leadership shortfalls.”76

Senior military and defense officials, including the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Gen. Mark Milley, have stated that withdrawing from Syria would compromise this progress and enable the “resurgence” of ISIS.77 But the United States is only one of many local and external actors in Syria who want to prevent the reconstitution of ISIS’s territorial caliphate.78 The Syrian government, Turkey, the SDF, Russia, Iran, and Iranian-backed militias may disagree on how Syria should be governed, but all of them agree that keeping ISIS contained suits their interests. Russian, Syrian, and Turkish military forces have all acted against ISIS in the past, either through airstrikes or coordinated ground offensives. In 2016, Turkey launched a unilateral military operation in northern Syria in part to degrade ISIS’s presence along a section of the Syrian-Turkish border.79 In May 2023, the Turkish intelligence service reportedly played a role in the death of ISIS leader Abu Hussein al-Qurashi, who was located in northwestern Syria.80 The Russian Air Force continues to conduct periodic counter-ISIS operations in the central Syrian desert, as does the Syrian army.81 These operations are likely to increase, not decrease, in the event of a U.S. withdrawal.

Territorial control in Syria’s Civil War

Regime forces have consolidated control over more than half of Syria since the destruction of the ISIS territorial caliphate. But even though ISIS remnants only pose a local threat, 900 U.S. forces remain in Syria to ensure the group’s “enduring defeat.”

As stated earlier, U.S. officials claim that a U.S. presence in eastern Syria makes the resumption of intra-Syrian negotiations more likely. But the reality proves otherwise. While Assad certainly hopes to reclaim the eastern oil fields to mitigate his budgetary problems, his political longevity does not depend on them. Some of the oil fields in the Syrian provinces of Deir-ez-Zor and Hasakah have been outside the Syrian government’s remit for a decade, yet Assad remains as resistant to proposals that dilute his power today as he was when the war started. The Syrian Constitutional Committee, a U.N.-led body staffed with members nominated by the Syrian government, opposition, and civil society that seeks to re-write Syria’s Constitution as a step toward free and fair elections, remains paralyzed due to Assad’s obstructionism. It has not met in over a year.82

Instead of being a point of leverage, U.S. troop deployments in Syria are a burden and source of risk. U.S. troops and contractors are periodically under the threat of drone and rocket attacks perpetrated by Iranian-supported militias, some of which result in casualties. U.S. troops based in Syria and Iraq were attacked 83 times between January 2021 and March 2023.83 In March 2023, one American contractor was killed and five U.S. soldiers were wounded when a drone of “Iranian-origin” exploded at a coalition base in northeast Syria.84 The United States immediately retaliated, striking facilities in Syria affiliated with Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).85 U.S. airstrikes can have short-term effects, including the destruction of arms caches and the death of enemy fighters. But they are purely punitive and evidently fail to deter follow-on attacks by the militias, resulting in a tit-for-tat escalation that risks a wider war with Iran. Rocket and drone strikes on U.S. positions are liable to continue for as long as U.S. forces are on the ground.

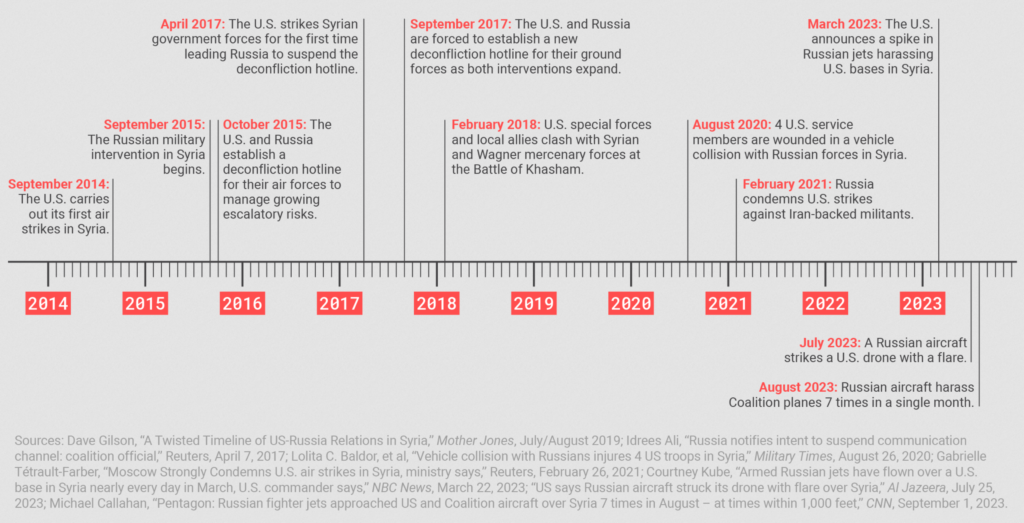

Timeline of U.S.-Russian escalation in Syria

U.S. and Russian forces in Syria have repeatedly brushed up against each other since 2015. In one instance, hundreds of Wagner mercenaries were killed during a battle with U.S. forces. More recently, Russian forces in Syria have become more comfortable taking risky actions like harassing U.S. bases and drones.

Advocates of a continuous U.S. troop presence in Syria also argue that withdrawal would result in a vacuum that would be filled by Russia and Iran. This is wrong for three reasons. First, the primary beneficiary of any vacuum left by the U.S departure will be the Syrian government; outside powers like Russia and Iran do not have the resources for an extended commitment and might even lose interest as Assad’s writ expands.86 Second, since Russia and Iran will always have some degree of influence in Syria, such a formulation effectively rules out any U.S. troop departure for any reason. Third, there are no outside “winners” in Syria, which will remain an unproductive, resource-poor, and sectarian-laced country with multiple armed factions for years to come.87 It is difficult to see how Russia and Iran would be considered the winners of the Syrian conflict if they were forced to manage these problems.

Finally, engagements with Russian military personnel are a growing escalation risk for U.S. personnel. The Russian Air Force is no longer respecting deconfliction protocols designed to limit incidents between U.S. and Russian forces.88 In some cases, Russian aircraft have violated them as many as three or four times in a single day.89 During three consecutive days in July 2023, Russian fighter aircraft forced U.S. drone operators to fly off course in order to avoid a collision.90 The trend continued in August 2023.91 Russian military vehicles have sideswiped U.S. vehicles, Russian pilots carrying munitions have flown low over joint U.S.-SDF patrols, and Russian surveillance aircraft have sought to collect information about the al-Tanf garrison. While the probability of a direct clash between two nuclear-armed powers remains low, the potentially catastrophic consequences of such a clash occurring, accidental or otherwise, vastly outweigh whatever minimal counterterrorism gains a lasting U.S. deployment might bring.

Mapping out a new Syria policy

Today, the United States seeks to accomplish two major goals: (1) the enduring defeat of ISIS and (2) pressuring Assad into a U.N.-led political process that will ultimately lead to the establishment of a multi-party democracy in Syria. Neither is necessary for U.S. national security. The former involves excessive risk for an unfeasible objective over an indefinite timetable while the latter is highly unlikely and causes pointless harm to Syrians. The United States should be realistic about what it can accomplish, recognize when past policies have failed, roll back sanctions, and end its military presence, thereby reducing unnecessary costs.

Recommendation 1: Withdraw all U.S. forces from Syria

The risks associated with a lingering U.S. force presence in Syria outweigh the perceived counterterrorism benefits. U.S. troops were originally deployed for a limited, specific mission with clear metrics: destroying the ISIS territorial caliphate. This mission was achieved when the U.S.-partnered SDF retook the last small town under ISIS’s control in 2019. Rather than declare the mission a success and withdraw, multiple U.S. administrations have since expanded the mission to the “enduring defeat” of ISIS. The word “enduring” suggests the United States seeks to neutralize every fighter under the ISIS umbrella or destroy the organization in its entirety. This is effectively impossible and a recipe for a perpetual military presence. Terrorist organizations can survive in some form without posing much risk beyond their immediate environs.92 Despite more than twenty years of military pressure, Al-Qaeda is still in existence but carries out few if any attacks in the West.

Rather than maintain an open-ended deployment, the United States should withdraw all troops from Syria and hand primary responsibility to local actors for managing the organization’s remnants. All of these local actors possess a strong aversion to an ISIS resurgence, and none of them wishes to see ISIS flourish in their areas. Some, like the Syrian Kurds, were combatting ISIS even before the United States intervened with airstrikes, arms supplies, and training. The alternative, permitting ISIS to recuperate, would be an existential danger to their communities. Thanks to U.S. equipment and mentoring, the Kurds are far more operationally capable today than they were in 2014. The incentives to continue the counter-ISIS fight will persist long after the United States is gone.

Claims that a troop withdrawal would be high risk for U.S. security are refuted by ISIS’s current unimpressive operational capabilities, the incentive structure of local actors, including the Syrian government, who will retain a long-term interest in degrading ISIS for their own reasons, and over-the-horizon strike capabilities the U.S. counterterrorism apparatus has built since the 9/11 attacks.93 The United States has demonstrated multiple times, including during the July 2022 drone strike against Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Afghanistan, that a constant ground presence is not required to track and kill high-profile terrorists in challenging environments.94 The United States and its partners in Europe and the Middle East could continue funding the SDF’s makeshift prison system, although the best solution is a large-scale repatriation of ISIS fighters to their countries of origin for prosecution.

Recommendation 2: Revise U.S. Syria sanctions to ensure humanitarian aid is received

The United States is unlikely to normalize relations with Syria as long as Assad is in power. Even if Assad departed, his replacement would likely be a creature of the political system the Assad family has built and maintained for the last half-century. Syria will remain a pariah in the West for the foreseeable future, which means diplomatic and economic dealings will be limited.

Yet treating the Syrian government as a permanent pariah is a form of collective punishment. Civilians who have nothing to do with their government’s actions are being penalized for them.

The United States should modify its sanctions regime against Syria to ensure humanitarian organizations can function properly and serve the Syrian population effectively. More specifically, the United States should stop blocking third-party attempts to finance reconstruction in government-controlled areas, where more than two-thirds of the Syrian people live, to make a moral point about the Syrian government’s brutal behavior. These sanctions, codified by the Caesar Act, have not affected Assad’s conduct; they have provided Damascus with a convenient scapegoat for Syria’s socioeconomic crisis and have done nothing to meet the policy objective the law is meant to achieve: inducing Assad to stop suppressing his people and “support a transition to a government in Syria that respects the rule of law, human rights, and peaceful co-existence with its neighbors.”95 The most fool-proof way of accomplishing this is by overturning the Caesar Act or, alternatively, allowing it to sunset in 2025. In the interim, the United States should utilize the waiver in the Caesar Act, which allows the president to bypass financial sanctions if doing so is in the interest of U.S. national security. The Treasury Department should also publish unambiguous guidelines for banks around the world spelling out which Syria-related financial activity is and is not permitted. The Treasury’s current guidance documents are riddled with difficult-to-understand exemptions and conditions, causing banks to opt for over-compliance and defeating the purpose of current waivers.

Recommendation 3: Communicate with the Syrian government on critical issues

The depravity of the Syrian government’s conduct during the civil war is indisputable. Assad has perpetrated a list of atrocities over the last decade in order to win a conflict he regarded as existential. U.S.-Syria relations will remain in an adversarial state for the short- and medium-term.

Even so, the United States has an interest in preserving flexibility in its foreign relations. The lack of diplomatic normalization should not translate into a lack of communication between U.S. and Syrian officials when such contact can help meet core U.S. security objectives in the Middle East. Maintaining as many intelligence relationships as possible to meet U.S. security goals is a common-sense measure. The United States did exactly that during its arms control diplomacy with various Soviet leaders, all of whom were brutal in their own right. The United States never cut diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union even when Josef Stalin, a man responsible for millions of deaths before World War II, was in charge.96 Today, the United States shares information with the Taliban about a mutual adversary, Islamic State-Khorasan, despite the United States having fought Taliban insurgents for two decades.97 Moral scruples will have to be set aside in the Middle East, a region consisting of countries, like Syria, that have poor human rights records, authoritarian governance, and long-standing partnerships with U.S. foes. Washington and Damascus will never agree on how Syria should be governed or how (or even whether) to pursue accountability for past crimes, but the two countries share a mutual interest in safeguarding against ISIS’s recuperation. To the extent business-like relations can be fruitful in meeting that goal, the United States should unapologetically pursue them.

Recommendation 4: Dismantle any U.S. roadblocks to Syrian Kurds negotiating with the Assad government

Despite Assad having prevailed, Syria remains divided between various stakeholders with competing interests. The United States has contributed to this division by discouraging the Syrian-Kurdish authorities in the northeast from exploring or pursuing a rapprochement with Damascus.98 U.S. opposition has had consequences for the Kurds, who have been forced to lean heavily on the U.S. troop presence for their own protection and whose relations with other stakeholders like Russia and Assad are damaged as a result. The United States, meanwhile, has put itself in the position of serving as the Kurds’ de facto security guarantor.

To help extricate itself from an unauthorized and unnecessary security commitment, the United States should limit its involvement in intra-Syrian political affairs, let the Syrians make their own political arrangements, and step aside so the Kurds can finally make independent decisions. The Syrian Kurdish administration is open to negotiating with the Syrian government on a long-term agreement, whereby the Kurds are granted some political and economic autonomy in exchange for hosting some of the nearly millions of Syrian refugees located in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey, and has even enlisted the UAE’s assistance as a mediator.99 Any negotiation between the Syrian Kurds and the Syrian government will be difficult, involving issues such as security sector reform, the presence of the Syrian army in the northeast, the sharing of oil revenue, and changes to the Syrian constitution. It is possible, if not likely, that talks could fail. But the United States should support the process, as Syrian Kurdish representatives are requesting.100

The U.S. military presence in Syria long ago lost its utility

With the ISIS territorial caliphate extinguished and under consistent military pressure, the U.S. military presence in Syria has lost its utility. Minor flare-ups in violence aside, the civil war has concluded on the Syrian government’s terms and Assad is slowly being re-incorporated into the regional fold. The years-long U.S. policy of sustaining sanctions on the Syrian economy until Assad agrees to democratize is not only a lost cause, but also a recipe for condemning millions of Syrians to an endless socioeconomic morass. Any sensible change in approach can only begin if the United States grasps the current realities in Syria, stops chasing unrealistic objectives, and recognizes the costs of the status quo.

Endnotes

1 Daniel DePetris, “It is Time for U.S. Troops to Leave Syria,” Defense Priorities, May 10, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/it-is-time-for-us-troops-to-leave-syria.

2 J.P. Lawrence, “U.S. Troop Level Reduction in Middle East Likely As Focus Shifts Elsewhere,” Stars and Stripes, January 14, 2022, https://www.stripes.com/theaters/middle_east/2022-01-14/centcom-central-command-drawdown-iraq-afghanistan-kuwait-saudi-arabia-4289137.html.

3 Daniel L. Davis, “Debunking the Safe Haven Myth,” Defense Priorities, May 6, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/debunking-the-safe-haven-myth.

4 John Hoffman, “Neither Russia nor China Could Fill a U.S. Void in the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, September 15, 2021, https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/09/15/neither-russia-nor-china-could-fill-a-u-s-void-in-the-middle-east/.

5 Justin Logan, “The Case for Withdrawing from the Middle East,” Defense Priorities, September 30, 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/the-case-for-withdrawing-from-the-middle-east.

6 Statistical Review of World Energy, BP, 2021, https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-oil.pdf.

7 Austin Carson and Michael Poznansky, “The Logic for (Shoddy) U.S. Covert Action in Syria,” War on the Rocks, July 21, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/07/the-logic-for-shoddy-u-s-covert-action-in-syria/.

8 Philip H. Gordon, “The False Promise of Regime Change: Why Washington Keeps Failing in the Middle East,” Foreign Affairs, October 7, 2020, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/middle-east/2020-10-07/false-promise-regime-change. See also Gordon, Losing the Long Game: The False Promise of Regime Change in the Middle East (New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press, 2020).

9 Mark Mazzetti and Ali Younes, “C.I.A. Arms for Syrian Rebels Supplied Black Market, Officials Say,” New York Times, June 26, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/27/world/middleeast/cia-arms-for-syrian-rebels-supplied-black-market-officials-say.html.

10 Mark Mazzetti, Adam Goldman, and Michael S. Schmidt, “Behind the Sudden Death of a $1 Billion Secret C.I.A. War in Syria,” New York Times, August 2, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/02/world/middleeast/cia-syria-rebel-arm-train-trump.html.

11 Rex W. Tillerson, “Remarks on the Way Forward for the United States Regarding Syria,” Hoover Institute, January 17, 2018, https://tr.usembassy.gov/remarks-way-forward-united-states-regarding-syria/.

12 Paul Sonne and Missy Ryan, “Bolton: U.S. forces will stay in Syria until Iran and its proxies depart,” Washington Post, September 24, 2018, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/bolton-us-forces-will-stay-in-syria-until-iran-and-its-proxies-depart/2018/09/24/be389eb8-c020-11e8-92f2-ac26fda68341_story.html.

13 Michael Doran and David Asher, “Transcript: Maximum Pressure on the Assad Regime for its Chemical Weapons Use and Other Atrocities,” Hudson Institute, May 15, 2020, https://www.hudson.org/national-security-defense/transcript-maximum-pressure-on-the-assad-regime-for-its-chemical-weapons-use-and-other-atrocities.

14 Tricia Bacon, Austin C. Doctor, and Jason Warner, “A Global Strategy to Address the Islamic State in Africa,” International Centre for Counter-Terrorism, June 29, 2022, https://www.icct.nl/publication/global-strategy-address-islamic-state-africa.

15 Geir O. Pedersen, “United Nations Special Envoy for Syria Geir O. Pedersen Briefing to the Security Council,” August 23, 2023, https://specialenvoysyria.unmissions.org/sites/default/files/2023-07-24_secco_un_special_envoy_for_syria_mr._geir_o._pedersen_briefing_as_delivered.pdf.

16 Eric Schmitt, “Conflict in Syria Escalates Following Attack that Killed a U.S. Contractor,” New York Times, March 24, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/24/us/politics/syria-us-contractor-killed-iran-drone.html.

17 Hamidreza Azizi, “Integration of Iran-backed Armed Groups into the Iraqi and Syrian Armed Forces: Implications for Stability in Iraq and Syria,” Small Wars & Insurgencies 33, no.3 (2022): 499–527, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592318.2021.2025284.

18 United Nations Refugee Agency, Seventh Regional Survey on Syrian Refugees’ Perceptions & Intentions on Return to Syria, June 2022, 12, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/93760.

19 U.S. Department of State, 2023 Condition (10)(C) Annual Report on Compliance with the Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), April 18, 2023, https://www.state.gov/2023-condition-10c-annual-report-on-compliance-with-the-chemical-weapons-convention-cwc/.

20 Aaron Stein, “Assessing the Biden Administration’s Interim Syria Strategy,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, June 15, 2021, https://www.fpri.org/article/2021/06/assessing-the-biden-administrations-interim-syria-strategy/.

21 The Path Forward on U.S.-Syria Policy: Strategy and Accountability: Hearing Before the Comm. On Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 117 Cong. 2 (2022), https://www.congress.gov/117/chrg/CHRG-117shrg49629/CHRG-117shrg49629.pdf.

22 Faysal Abbas Mohamad, “The Astana Process Six Years On: Peace or Deadlock in Syria?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 1, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/90298.

23 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Pub. L. No. 116–192 (2019), https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senate-bill/1790/text.

24 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020.

25 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020.

26 United Nations Security Council, Resolution 2254, S/RES/2254 (December 18, 2015), https://www.securitycouncilreport.org/atf/cf/%7B65BFCF9B-6D27-4E9C-8CD3-CF6E4FF96FF9%7D/s_res_2254.pdf.

27 U.S. Department of State, “Special Online Press Briefing with Barbara Leaf, Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs,” March 30, 2023, https://www.state.gov/online-briefing-with-barbara-a-leaf-assistant-secretary-of-state-for-near-eastern-affairs/.

28 Jim Miklaszewski and Cassandra Vinograd, “U.S. Bombs ISIS Sites in Syria and Targets Khorasan Group,” NBC News, September 23, 2014, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/ncna209421.

29 Continuing Appropriations Resolution, 124, H.R. (2014), https://www.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/house-joint-resolution/124/text; Jonathan Weisman and Jeremy W. Peters, “Congress Gives Final Approval to Aid Rebels in Fight with ISIS,” New York Times, September 18, 2014, https://www.nytimes.com/2014/09/19/world/middleeast/senate-approves-isis-bill-avoiding-bigger-war- debate.html.

30 Greg Jaffe and Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “Obama Seeks to Intensify Operations in Syria with Special Ops Troops,” Washington Post, October 30, 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/obame-decides-on-small-special-operations-force-for-syria/2015/10/30/a8f69c0e-7f13-11e5-afce-2afd1d3eb896_story.html.

31 Paul McLeary, “Pentagon Acknowledges 2,000 Troops in Syria,” Foreign Policy, December 6, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/12/06/pentagon-acknowledges-2000-troops-in-syria/.

32 Statement by Dr. Celeste Wallander, Assistant Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs, Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Office of the Secretary of Defense, Before the 118th Congress Committee on Armed Services, U.S. House of Representatives, March 23, 2023, https://armedservices.house.gov/sites/republicans.armedservices.house.gov/files/20230221%20ASD%20ISA%20SFR.pdf.

33 U.S. Central Command, “August 2023 Month in Review: The Defeat ISIS Mission in Iraq and Syria,” press release, September 8, 2023, https://www.centcom.mil/MEDIA/PRESS-RELEASES/Press-Release-View/Article/3519821/august-2023-month-in-review-the-defeat-isis-mission-in-iraq-and-syria/.

34 “New Country Classifications by Income Level: 2018–2019,” World Bank Blogs, July 1, 2018, https://blogs.worldbank.org/opendata/new-country-classifications-income-level-2018-2019.

35 “GDP (current US$) – Jordan, Syrian Arab Republic,” World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?locations=JO-SY.

36 International Rescue Committee, “11 Years of Violence Against Health Care in Syria,” March 8, 2022, https://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/document/6677/factsheet11ysyriaattacksonhealthcare150322.pdf.

37 Amr Alsarraj and Philip Hoffman, “The Syrian Political Opposition’s Path to Irrelevance,” Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center, May 15, 2020, https://carnegie-mec.org/2020/05/15/syrian-political-opposition-s-path-to-irrelevance-pub-81799.

38 Raja Abdulrahim and Dion Nissenbaum, “Evacuations Set to Begin as Assad Reclaims Aleppo,” Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2016, https://www.wsj.com/articles/aleppo-civilians-have-nowhere-safe-to-run-red-cross-says-1481628920.

39 Amberin Zaman, “Syria’s Kurds Make Their Own Pitch as Arab States Court Assad,” Al-Monitor, April 20, 2023, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/04/syrias-kurds-make-their-own-pitch-arab-states-court-assad.

40 Sam Heller, “The Upsides of Syrian Normalization: Assad is Heinous, but Arab Isolation of Him Did More Harm than Good,” Foreign Affairs, August 14, 2023, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/syria/upsides-syrian-normalization-assad.

41 Daniel DePetris, “The West and its Arab Partners are Heading for a Collision on Syria Policy,” Royal United Services Institute, May 19, 2023, https://rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/west-and-its-arab-partners-are-heading-collision-syria-policy.

42 “Saudi Arabia is Reconciling with Regimes it Once Tried to Topple,” Economist, February 23, 2023, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2023/02/23/saudi-arabia-is-reconciling-with-regimes-it-once-tried-to-topple.

43 “UAE President Receives President of Syria,” Emirates News Agency (WAM), March 19, 2023, https://wam.ae/en/details/1395303140285.

44 Ayesha Rascoe, “Arab countries are normalizing relations with Syria, over a decade after the uprising,” NPR, April 16, 2023, https://www.npr.org/2023/04/16/1170293920/arab-countries-are-normalizing-relations-with-syria-over-a-decade-after-the-upri.

45 Vivian Yee, “Arab League Votes to Readmit Syria, Ending a Nearly 12-Year Suspension,” New York Times, May 7, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/07/world/middleeast/arab-league-syria.html.

46 U.S. Department of State, “Secretary Blinken’s Call with Jordanian Minister of Foreign Affairs Safadi,” May 4, 2023, https://www.state.gov/secretary-blinkens-call-with-jordanian-minister-of-foreign-affairs-safadi/.

47 Karam Shaar and Caroline Rose, “The Syrian Regime’s Captagon End Game,” New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy, May 2023 https://newlinesinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/20230525-Dossier-Syrian-Regime-Captagon-NLISAP-1-1.pdf.

48 Steven Simon and Joshua Landis, “H.R. 3202: Analyzing Legislative Efforts to Block Arab Engagement with Syria,” Quincy Institute, June 9, 2023, https://quincyinst.org/report/analyzing-legislative-efforts-to-block-arab-engagement-with-syria/.

49 Mona Yacoubian, “Syria’s Stalemate Has Only Benefitted Assad and His Backers,” United States Institute of Peace, March 14, 2023, https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/03/syrias-stalemate-has-only-benefitted-assad-and-his-backers.

50 United Nations, “Following 12 Years Filled with War, Sanctions, Syria Faces Worsening Humanitarian, Economic Crisis of ‘Epic Proportions’, Special Envoy Tells Security Council,” January 25, 2023, https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15182.doc.htm.

51 United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, “The Human Cost of the Syria Crisis is Astronomical. The World Must Continue to Support the People and Intensify Efforts to End the Crisis,” June 14, 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/news/announcements/human-cost-syria-crisis-astronomical-world-must-continue-support-people-and.

52 United Nations, “Briefers Stress to Security Council Syria’s Worsening Situation Needs Fully Funded Humanitarian Response Plan, 12-Month Extension of Cross-Border Aid Mechanism,” https://press.un.org/en/2023/sc15339.doc.htm.

53 U.S. Department of State, “The United States Announces $920 Million in Additional Humanitarian Assistance for Syria,” June 15, 2023, https://www.state.gov/the-united-states-announces-920-million-in-additional-humanitarian-assistance-for-syria/.

54 Syrian Sanctions Regulations, C.F.R. § 542.516 (2014), https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-31/subtitle-B/chapter-V/part-542/subpart-E/section-542.516.

55 General License No. 23 Authorizing Transactions Related to Earthquake Relief Efforts in Syria, February 9, 2023, https://ofac.treasury.gov/media/931106/download?inline. The February 2023 Treasury Department waiver expired on August 8, 2023.

56 International Crisis Group, “Sanctions, Peacemaking and Reform: Recommendations for U.S. Policymakers,” August 28, 2023, https://www.crisisgroup.org/united-states/8-sanctions-peacemaking-and-reform-recommendations-us-policymakers.

57 Gabija Leclerc, “Impact of Sanctions on the Humanitarian Situation in Syria,” European Parliamentary Research Service, June 2023, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/749765/EPRS_BRI(2023)749765_EN.pdf.

58 United Nations Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights, “UN Expert Calls for Lifting of Long-Lasting Unilateral Sanctions ‘Suffocating’ Syrian People,” November 10, 2022, https://www.ohchr.org/en/node/104160.

59 Raya Jalabi, “Syria’s State Capture: The Rising Influence of Mrs. Assad,” Financial Times, April 2, 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/a51c6227-0c93-4fe1-aca7-25783a43708f.

60 Zaki Mehchy and Rim Turkmani, “Understanding the Impact of Sanctions on the Political Dynamics in Syria,” London School of Economics and Political Science (2021), http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/108412/1/CRP_understanding_impact_of_sanctions_on_political_dynamics_syria.pdf.

61 Enea Gjoza, “Counting the Costs of Financial Warfare: Recalibrating Sanctions to Preserve U.S. Financial Hegemony,” Defense Priorities, November 11, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/counting-the-cost-of-financial-warfare.

62 Robert A. Pape, “Why Economic Sanctions Do Not Work,” International Security 22, no. 2 (Fall 1997): 90–136, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539368.

63 Daniel DePetris, “‘Maximum Pressure’ Harms Diplomacy and Increases Risks of War with Iran,” Defense Priorities, November 19, 2021, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/maximum-pressure-harms-diplomacy-and-increases-risks-of-war-with-iran.

64 Agathe Demarais, “Why Sanctions Don’t Work Against Dictatorships,” Journal of Democracy, November 2022, https://journalofdemocracy.org/why-sanctions-dont-work-against-dictatorships/.

65 Dursun Peksen and A. Cooper Drury, “Coercive or Corrosive: The Negative Impact of Economic Sanctions on Democracy,” International Interactions 36, no.3 (2010): 240–264, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/03050629.2010.502436.

66 Aron Lund, “How Assad’s Enemies Gave Up on the Syrian Opposition,” Century Foundation, October 17, 2017, https://tcf.org/content/report/assads-enemies-gave-syrian-opposition/.

67 Samuel Charap, Elina Tryger, and Edward Geist, “Understanding Russia’s Intervention in Syria,” RAND Corporation, 2019, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3180.html.

68 Pierre Boussel, “The Quds Force in Syria: Combatants, Units, and Actions,” CTC Sentinel 16, no. 6 (June 2023), https://ctc.westpoint.edu/the-quds-force-in-syria-combatants-units-and-actions/.

69 William Roebuck, “Keep US Troops in Syria,” Defense One, January 10, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/ideas/2023/01/keep-us-troops-syria/381642/.

70 Joe Biden, “Statement by Vice President Joe Biden on the Consequences of Donald Trump’s Decision to Remove Troops from Syria,” Medium, October 10, 2019, https://medium.com/@JoeBiden/statement-by-vice-president-joe-biden-on-the-consequences-of-donald-trumps-decision-to-remove-8104a2c21ae4.

71 Charles Lister, “We’re Abandoning Syria and Our D-ISIS Policy,” Middle East Institute, May 5, 2023, https://www.mei.edu/publications/were-abandoning-syria-and-our-d-isis-policy.

72 Robert P. Storch, Diana R. Shaw, and Nicole L. Angarella, Operation Inherent Resolve: Lead Inspector General Report to the United States Congress (2023), 13, https://media.defense.gov/2023/Aug/03/2003274284/-1/-1/1/LEAD%20INSPECTOR%20GENERAL%20FOR%20OPERATION%20INHERENT%20RESOLVE%20Q3.PDF.

73 UN Security Council, Resolution, S/2023/95, “Letter Dated 13 February 2023 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee Pursuant to Resolutions…Concerning Islamic State in Iraq and Levant (Da’esh), Al-Qaida, and Associated Individuals, Groups, Undertakings and Entities Addressed to the President of the Security Council,” https://undocs.org/Home/Mobile?FinalSymbol=S%2F2023%2F95&Language=E&DeviceType=Desktop&LangRequested=False.

74 Rukmini Callimachi, “Was Orlando Shooter Really Acting for ISIS? For ISIS, It’s All the Same,” New York Times, June 12, 2016, https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/13/us/orlando-omar-mateen-isis.html.

75 Storch, Shaw, and Angarella, Operation Inherent Resolve, 59.

76 Office of the Director of National Intelligence, Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community, February 6, 2023, https://www.dni.gov/files/ODNI/documents/assessments/ATA-2023-Unclassified-Report.pdf.

77 Helene Cooper, “In Syria, Milley Says U.S. Troops Are Still Needed to Counter ISIS,” New York Times, March 4, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/04/us/politics/syria-milley-isis-kurds-troops.html.

78 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War: The Case for U.S. Military Withdrawal,” Defense Priorities, May 29, 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

79 Francesco Siccardi, “How Syria Changed Turkey’s Foreign Policy,” Carnegie Europe, September 14, 2021, https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/09/14/how-syria-changed-turkey-s-foreign-policy-pub-85301.

80 Orhan Coskun, Ahmed Rasheed, and Timour Azhari, “Exclusive: Turkish Raid Prompted ISIS Leader to Detonate Suicide Vest,” Reuters, May 2, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkish-raid-prompted-isis-leader-detonate-suicide-vest-2023-05-02/.

81 Storch, Shaw, and Angarella, Operation Inherent Resolve, 55–56.

82 Geir O. Pedersen, “United Nations Special Envoy for Syria Geir O. Pedersen Briefing to the Security Council,” August 23, 2023, https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/4019727?ln=en#record-files-collapse-header.

83 Jeff Schogol, “Iran Has Attacked US Troops 83 Times Since Biden Became President,” Task & Purpose, March 28, 2023, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/iran-attacks-us-military-iraq-syria-biden/.

84 Eric Schmitt, “Attack Contractor Killed in Drone Attack on Base in Syria,” New York Times, March 23, 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/23/us/politics/syria-drone-attack-us-base.html.

85 U.S. Department of Defense, “U.S. Conducts Airstrikes in Syria in Response to Deadly UAV Attack,” press release, March 23, 2023, https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/3339691/us-conducts-airstrikes-in-syria-in-response-to-deadly-uav-attack/.

86 Benjamin H. Friedman, “Don’t Fear Vacuums: It’s Safe to Go Home,” Defense Priorities, December 7, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/dont-fear-vacuums-its-safe-to-go-home.

87 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “The Terrible Case for Staying in Syria,” War on the Rocks, May 30, 2019, https://warontherocks.com/2019/05/the-terrible-case-for-staying-in-syria/.

88 Andrew S. Weiss and Nicole Ng, “Collision Avoidance: The Lessons of U.S. and Russian Operations in Syria,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 20, 2019, https://carnegieendowment.org/2019/03/20/collision-avoidance-lessons-of-u.s.-and-russian-operations-in-syria-pub-78571.

89 Jeff Seldin, “US Commander Accuses Russia of ‘Buffoonery in the Air’ in Syria,” Voice of America, June 21, 2023, https://www.voanews.com/a/us-commander-accuses-russia-of-buffoonery-in-the-air-in-syria/7146914.html.

90 U.S. Air Force Central, “Russian Unprofessional Behavior over Syria—7 July 2023,” July 7, 2023, https://www.afcent.af.mil/News/Article/3451842/russian-unprofessional-behavior-over-syria-7-july-2023/.

91 Michael Callahan, “Pentagon: Russian Fighter Jets Approached US and Coalition Aircraft over Syria 7 Times in August—at Times within 1,000 Feet,” CNN, September 1, 2023, https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/01/politics/russian-fighter-jets-us-coalition-aircraft/index.html.

92 Arie Perliger and Leonard Winberg, “How Terrorist Groups End,” CTC Sentinel 3, no. 2 (February 2010), https://ctc.westpoint.edu/how-terrorist-groups-end/#:~:text=Yet%20with%20the%20exception%20of,between%20five%20and%20ten%20years.

93 Natalie Armbruster, “Apply the Logic of the Afghanistan Withdrawal to Syria,” Defense Priorities, March 7, 2022, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/apply-the-logic-of-the-afghanistan-withdrawal-to-syria.

94 The White House, “Background Press Call by a Senior Administration Official on a U.S. Counterterrorism Operation,” August 1, 2022, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/press-briefings/2022/08/01/background-press-call-by-a-senior-administration-official-on-a-u-s-counterterrorism-operation/.

95 National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2020, Pub. L. No. 116–192 (2019), 2291.

96 Timothy Snyder, “Hitler vs. Stalin: Who Killed More?” New York Review of Books, March 10, 2011, https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/03/10/hitler-vs-stalin-who-killed-more/.

97 David Ignatius, “In Afghanistan, the Taliban Has All but Extinguished Al-Qaeda,” Washington Post, September 14, 2023, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/09/14/al-qaeda-afghanistan-taliban-destroyed/.

98 Christopher Dickey and Spencer Ackerman, “The U.S. Spoiled a Deal that Might Have Saved the Kurds, Former Top Official Says,” Daily Beast, October 14, 2019, https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-us-spoiled-a-deal-that-might-have-saved-the-kurds-former-top-official-says.

99 Amberin Zaman, “Syria’s Kurds Turn to UAE to Ease Tensions with Assad,” Al-Monitor, May 3, 2023, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/05/syrias-kurds-turn-uae-ease-tensions-assad.

100 Zaman, “Syria’s Kurds Make their Own Pitch as Arab States Court Assad,” Al-Monitor, April 20, 2023, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2023/04/syrias-kurds-make-their-own-pitch-arab-states-court-assad.