As it turns 20, hard questions are being asked about the AU’s authority to resolve security challenges in Africa.

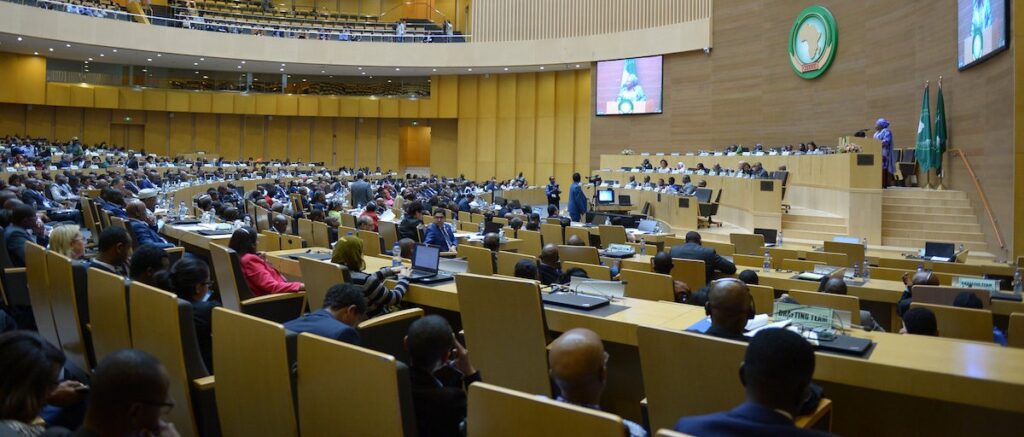

February’s African Union (AU) summit was symbolic in several ways. It was held in person in Addis Ababa after nearly two years of online meetings due to COVID-19, signalling a growing confidence in the management of the pandemic. For Ethiopian authorities, the summit was an opportunity to show the government’s control over the fragile security situation in the country.

AU Commission Chairperson Moussa Faki Mahamat’s opening speech was another positive surprise of the summit. He was uncharacteristically confrontational with heads of state, using lucid and courageous words to describe what he called the ‘immensity of African paralysis with regard to neighbouring homes that are going up in flames.’

Faki was referring to the AU’s uneven peace and security record in 2021, one year after its Commission was reformed and restructured. But he was also raising fundamental questions around the continental body’s authority to weigh in on challenges to state stability.

What does the AU need to exert more profound impacts on conflict situations? The time is right to ask this question. As the body turns 20, protracted and emerging conflicts are testing the coherence of the AU’s African Peace and Security Architecture and its goal of silencing the guns by 2030.

When facing crises, African governments use various strategies to limit the AU’s involvement

Based on philosopher Hannah Arendt’s definition, authority is generally understood as the ability to obtain consent without coercion. As a continental organisation, the AU draws its influence from the voluntary adherence of member states to the pan-African project. But governments often don’t back the AU when it tries to enforce its authority, especially on early action and conflict prevention.

When facing crises, African governments often resort to various strategies to limit the AU’s role. They politely reject its involvement in their internal affairs (Cameroon), contest its action when it’s already deployed (Somalia), sideline it in favour of regional bodies (Central African Republic and Mozambique), or just prefer working with better-resourced international actors (Libya and Sudan).

In inter-state disputes, such as those between Morocco-Algeria, Egypt-Ethiopia, Kenya-Somalia and Rwanda-Uganda, for example, the AU struggles to mediate due to the uneven interest from the states involved. If we add the AU Peace and Security Council’s inconsistent handling of unconstitutional changes of government in Mali and Chad, it could be argued that the AU faces a decline of authority. However the trend could be reversed if several structural and cyclical fragilities were addressed.

One systemic fragility is that most African states oppose any interference in their internal affairs. While the AU has normatively shifted from the non-interference position of its predecessor (the Organisation of African Unity) to non-indifference, the gap between a pro-active AU Commission and reluctant member states is huge. This causes inconsistencies in how the AU applies its rules and frameworks, which weakens the body.

Unlike the EU, joining the AU is not subject to anything other than geography

Another serious fragility is the relationship between member states and the AU. Unlike the European Union (EU), whose members must qualify to be included, joining the AU is subject only to geography. Despite strong rhetoric about how integrated the body is, the AU comprises highly heterogeneous types of governments with varied commitments to human rights. Most member states favour a traditional view of sovereignty that prevents any interference to boost governance and human rights.

The AU’s role as an entrepreneur of shared values is complicated because it doesn’t encourage the democratic convergence it needs from members, even though it has the power to issue sanctions in situations of unconstitutional government changes.

As the AU doesn’t provide subsidies or significant funds for economic modernisation, its value-add in the daily functioning of member states is limited. This means that African governments’ dependency on the AU is relatively minimal. The exception has been its significant role in fighting pandemics and epidemics, although this is more reactive than proactive.

The AU is an international organisation with as much authority and influence as its member states want to give it. Beyond fierce rhetoric, it remains unclear how much appetite African leaders have for effective continental integration that goes beyond pan-Africanist slogans.

It’s unclear how much appetite African leaders have for real continental integration

It could be argued that the African Continental Free Trade Area agreement (AfCFTA) illustrates a commitment to regional integration. But would the AU be able to settle, for example, trade disputes between Kenya and Somalia if it isn’t trusted as an impartial broker for political and security matters?

The success of any trade agreement depends on the independence and impartiality of dispute settlement mechanisms and the upholding of their decisions by signatory states. Over the years, African states have been uncomfortable with the decisions of regional legal bodies. Tanzania for example recently denied its people direct access to the African Court of Human and Peoples’ Rights, which is ironically headquartered in Arusha. It remains to be seen how AU member states respond to the AfCFTA dispute mechanism’s decisions.

As the AU marks its 20th anniversary, it is coming to the end of a cycle where member states intuitively respected its authority without needing to call on its binding instruments. To remain relevant, key AU member states must find a way to bridge the expectations-capabilities gap.

Should African states see integration and a limited degree of supranationalism as going against their interests, the focus will need to shift to greater regional cooperation that provides better added value. This would already be an impressive step on Africa’s road to integration.