Will Ukraine Bring Russia the Superpower Status It Seeks?

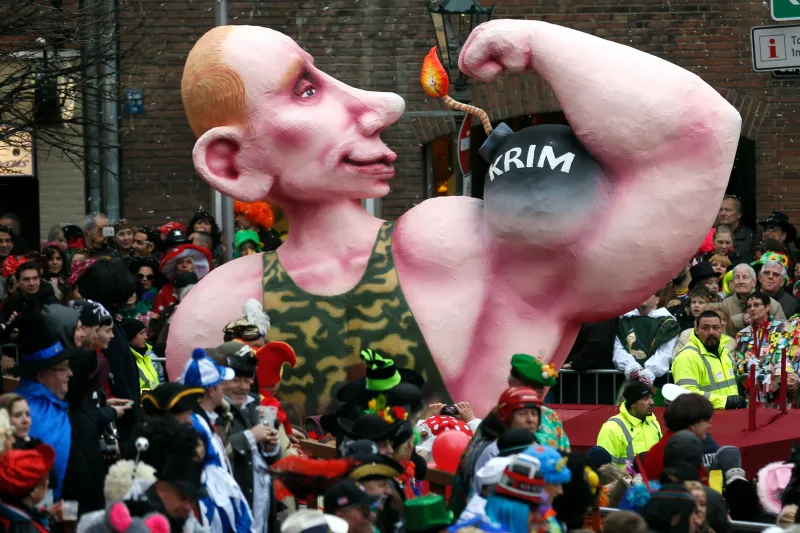

On Saturday, Russia invaded and effectively annexed Crimea, a Ukrainian peninsula in the Black Sea. In doing so, Russian President Vladimir Putin shrewdly took advantage of the political uncertainty that arose when Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s former kleptocratic president, took flight last week and was swiftly replaced by a hastily formed provisional government in Kiev. Russia might justify its behavior by speaking of a need to protect ethnic Russians but, in reality, the move was a thinly veiled attempt to forward Putin’s real agenda: reestablishing Russia as a resurrected great power.

The official Russian explanation for flooding Crimea with troops, who, dressed in uniforms without insignia, first showed up to “guard” two airports in Crimea and then the Crimean regional legislature, was that Russia was concerned about the treatment of the ethnic Russian minority within Ukraine, particularly in Crimea. The thin pretext was a law that Ukraine’s provisional parliament speedily passed after Yanukovych’s departure that downgraded the status of the Russian language relative to the Ukrainian language.

As U.S. President Barack Obama evidently mentioned during the 90-minute phone conversation he had with Putin after Russian troops first invaded Crimea, the Russian minority hardly constituted a reason to invade. After all, in 2008, when Putin sent forces to Georgia, another neighboring former Soviet state, he at least waited until a few houses were burned down in the ethnic Russian regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. At that point, he dispatched thousands of troops to “liberate” the persecuted Russian minority and, incidentally, establish Russian sovereignty and a lasting military presence in the regions.

In Crimea, however, tensions had not escalated beyond some pushing and shoving between ethnic Russians on the one side and ethnic Ukrainians and indigenous Crimean Tatars on the other. And the only people hurt in these skirmishes were ethnic Ukrainians. It makes little sense for Russia to squander the international goodwill it generated from the unexpectedly successful Sochi Olympics for a few million Russians living in Ukraine (only about 20 percent of the total Ukrainian population identify themselves as ethnic Russians), especially when there was little violence. Furthermore, it is especially hypocritical of Putin to cite Russian rights while he is busy persecuting gays and lesbians within Russia proper and imprisoning members of the Russian opposition, as he did earlier this week for the “crime” of standing outside a Moscow courthouse to hear the prison sentence of a group of Russian citizens who had legally protested Putin’s reelection in 2012.

As most observers understood all along, Putin’s endgame in Ukraine is not to protect persecuted Russians. One alternative explanation is national security. The Crimean peninsula is home to the Sevastopol naval base, which houses Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. In 2010, Ukraine agreed to lease the base to Russia until 2042. Russia certainly wouldn’t want the new Ukrainian government to seize Sevastopol or threaten it in any way. But that probably wouldn’t have happened anyway: The base generates income for Ukraine and the country has almost no military. Ukraine’s new leaders know that its few thousand active duty troops would be no match for Russian regular troops or special forces. Russia knows that, too, and likely understands that Ukraine’s new government would never have made a move on Sevastopol. Protecting the Black Sea Fleet cannot be Putin’s main driver, either.

Rather, as those who watched the opening ceremonies of the Olympic Games must have realized, Putin wants everyone to know that Russia is back. Putin’s mission with the Olympics, as with his last-minute diplomatic intervention in Syria last year to prevent a U.S. attack, is to remind the world that Russia is a greater power than ever. It is entitled to international respect, he believes, and it isn’t getting enough. It is also entitled to dominate its neighbors both economically and now, evidently, militarily.

Officials at all levels of the Russian Foreign Ministry and within the presidential administration truly believe that Russia has a natural sphere of political and economic influence. The media makes much of Putin’s infamous statement in 2001 that the collapse of the Soviet Union was “the worst geopolitical catastrophe since WWII,” often misunderstanding that to mean that Putin would like to see the resurrection of the Soviet Union. But a revitalized Soviet Union is not the endgame in Ukraine (nor was it in Georgia). Rather than the revival of a particular political and economic system guided, if somewhat cynically, by a communist ideology, he wants to reestablish what Russians historically—well before the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917—viewed as theirs. This includes Ukraine and Georgia but also the South Caucasus countries of Armenia, and possibly Azerbaijan, Belarus, and Moldova. Ukraine and Georgia are of particular importance to this mission because they sit on Europe’s borders.

But there are risks to this way of thinking: Russian nationalists (and Putin has become one) will remind you that Russian civilization began in Kievan Rus, a confederation of East Slavic tribes across Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia from the late ninth to the mid-13th centuries. They will also tell you that half of Ukraine speaks Russian. That might be true, but it is only because the Soviet Union had an official language policy requiring the teaching of Russian language in all schools across the Soviet Union, not because Ukrainians are basically Russians. Russian nationalists might view Ukrainians as “little brothers,” but the affection is one-sided. Ukrainians don’t view Russia as a friendly, if over protective, older sibling; they view it as an invading state.

Great powers assert themselves where they see their interests being threatened. If an independent Ukraine under a provisional, European-oriented government were to actually side with the West and leave Russia’s sphere of influence, then what would stop other nations from doing the same? And what would stop Western powers from gradually moving closer to Russia? From this perspective, the only thing to do was to act decisively to stop any further Western incursion. And there is little the West can do about it without risking a third World War.

For now, the only force powerful enough to stop Putin might just be the Russian people. One of his administration’s greatest fears is that something like the Ukrainian Orange Revolution of 2004 or EuroMaidan of 2013-2014 could somehow infect Russia with democratic revolutionary fervor. Pesky calls for free and fair elections, rule of law, due process, and equality have gotten in the way of maintaining order, growing the economy, and pilfering from state coffers. But wars, especially wars fought to protect brother Russians in a neighboring state, play well at home. In invading Ukraine, then, Putin has perhaps convinced two audiences—domestic and international—of his power.