Many in Moscow believe that the system of arms control created during the Cold War was advantageous to the West—and they want that to change.

For many decades, international security has depended on dialogue between Moscow and Washington on the topic of nuclear arms control. In recent years, however, this dialogue has all but ground to a complete halt, and the use of nuclear blackmail has spiraled. In Russia, there have been calls for nuclear strikes on Europe and for a “demonstrative nuclear explosion.” In May, Russia held tactical nuclear drills in response to the West’s so-called “direct support for terrorist actions against Russia.” Russian officials have even threatened to use strategic nuclear weapons against the West.

Moscow rejects Washington’s proposal to restart arms control talks. It has made it clear that this isn’t a priority, and that it will continue to break taboos until its demands in other areas are met. In other words, Russia is exploiting the U.S. desire for arms control.

Nuclear threats have become routine for the Kremlin. Every time Kyiv is supplied with new weapons, is given permission to use Western arms to strike Russian territory, or attacks Russia’s missile warning systems, Moscow resorts to nuclear threats. Ignoring the limits Washington has placed on its support for Ukraine, the Kremlin is doing everything it can to show that it doesn’t care about upholding arms control.

Indeed, Russia has been trying to bully the West with nuclear weapons for years. In 2018, Russian President Vladimir Putin attempted to muddy the waters by announcing the development of weapons not covered by the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START III), including the nuclear-powered Burevestnik long-range cruise missile and the Poseidon nuclear-capable super torpedo. Along with talk of modernizing its nuclear triad, this was all intended to underline Russia’s strategic edge, impress the U.S. establishment, and make Washington more accommodating on other issues.

Putin has dismissed U.S. proposals for talks on arms control as “demagoguery,” and apparently expects the West to accept Russia’s ultimatum issued in the run-up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. “We need guarantees. And the guarantees should be… ones that would satisfy us, that we would believe in,” the Russian leader said earlier this year.

Since the start of the fighting in Ukraine, Russia’s Defense Ministry has seen nuclear weapons as the sole obstacle to a war with NATO, while the Foreign Ministry approaches them as just another diplomatic tool. Accordingly, agreeing to nuclear arms control negotiations now would be seen in Moscow as a defeat.

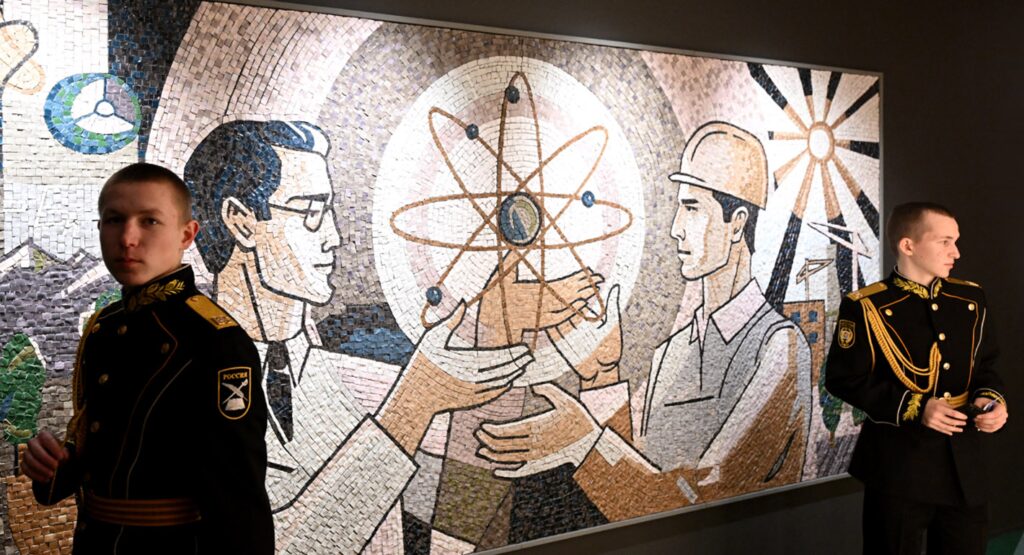

In addition, many in Russia believe that the Cold War–era arms control system was created on the West’s terms, and they want that to change. For them, the West’s involvement in Ukraine is the result of ineffective nuclear deterrence, and the 1962 Cuban missile crisis was an example of how to successfully use nuclear threats to achieve military-political goals.

In response to U.S. support for Kyiv, Russia has stationed nuclear weapons in Belarus, withdrawn from the Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, and suspended participation in START III. This is supposed to frighten Washington into dividing the world—or at least Europe—into spheres of influence. And it has yielded some results: U.S. pledges of support for Ukraine come with caveats, and Washington is pushing for talks on strategic arms control and a ban on nuclear weapons in space (Moscow, of course, rejects any initiative that would reduce tensions). Nevertheless, the Kremlin is a very long way from seeing Washington meet its maximalist demands. The United States is not reducing its support for Ukraine, nor is it preparing a Cuban missile crisis–style response.

This means Russia will continue escalating. Moscow’s options include changing its doctrine on nuclear weapons use, increasing weapons stockpiles, building a national missile defense system, revising its commitment not to be the first to deploy intermediate- and shorter-range missiles in Europe, increasing nuclear capabilities in the exclave of Kaliningrad, and even—as some experts propose—carrying out a “demonstrative nuclear explosion.”

With nuclear blackmail, Moscow is trying to recreate the world order that prevailed in the second half of the twentieth century. While the Kremlin sees this as a period of stability, in fact neither side trusted the other, and each continued to increase its arsenal and pursue its own interests. The same would be true today. A deal to end the war in Ukraine and carve up Europe would not make the world safer. In fact, it would convince the Kremlin of its own invincibility and make it more aggressive.

Moscow sees itself as the stronger side in Ukraine and, as such, is ready to wait out the West. In the meantime, the world can expect significant displays of nuclear power. Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov said in May that Russia would shelve the issue of “red lines,” and mirror the West’s nuclear threats. Unpredictable years of confrontation lie ahead.

First, we’re likely to see the development of new weapons, both real and modeled. Nuclear drones, hypersonic missiles, and lasers will be a constant feature of official speeches and military exercises. Second, nuclear weapons will be moved closer to the enemy. Third, strategic missile carriers and nuclear submarines will appear more often in border areas. Fourth, there will be a buildup of conventional weapons and troops in Europe as soon as funds and manpower are available (probably once the active phase of the war in Ukraine is over). Fifth, there will be an increase in the number and scale of military exercises. Sixth, there will be more military incidents. Seventh, we will return to a nuclear arms race. Finally, and most worryingly, nuclear arsenals could—at some point—be put on high alert.

Some of this is already under way. Russia has moved nuclear weapons to Belarus, and the United States is scouting for sites for a similar deployment. Moscow appears ready to lift the moratorium on the deployment of medium- and shorter-range missiles in Europe after Washington put ground-based Typhon missile systems in the Philippines. And experts in both Russia and the United States are trying to justify the buildup of strategic offensive weapons.

Moscow hopes its demands will be met after a changing of the guard in the West. Washington has similar hopes for Russia. It hasn’t forgotten how Mikhail Gorbachev’s arrival in 1985 led to nuclear arms control agreements and a stable Europe. These expectations mean that the current worrying trends could continue for years—at least for as long as Putin remains in office.