Key points

Due to an overly broad definition of threat, the United States currently commits far too many military resources to counterterrorism, especially in Africa.

The United States is pursuing military action against at least thirteen terrorist groups in Africa, but only one of those groups has the “global reach” to be a threat to Americans. Consequently, the U.S. military is fighting a slew of counterinsurgency—not counterterrorism—wars in Africa today, a strategy that borders on nation-building.

Counterintuitively, U.S. security assistance, training, and military activity in Africa since the 2000s has inadvertently aided the growth of terrorist groups in the region. Most concerning, U.S. policy today could be helping to inspire the next generation of global jihadists tomorrow, intent on attacking the United States and its closest democratic allies.

U.S. military activity in Africa has expanded significantly over the past decade and a half and this trend will likely continue even further without an intentional course correction. The potential for further mission creep and overexpansion is high.

Washington should wind down direct military activity and close most military bases in Africa, while also curbing security assistance to local regimes.

Over-militarized U.S. counterterrorism in Africa

The United States has been conducting counterterrorism in Africa for nearly two decades. It is time to face the fact that this well-intentioned policy has not only been disappointing in its results but counterproductive, bringing unintended negative consequences. Counterterrorism in Africa needs re-thinking and significant rightsizing if the United States wants to avoid unnecessary conflict and strategic overstretch at a time when new challenges abroad demand more attention.

There are two problems with U.S. counterterrorism in Africa today. First, the United States is applying too much force against too little threat. Terrorist groups that pose a threat to U.S. national interests are those with global reach, meaning a demonstrated intent—notably, by an attack or attempted attack—to strike the United States and its closest democratic allies in Europe and Asia.

Today, very few Islamist terrorist groups meet this global reach threshold of intent. The main exceptions are ISIS central in Iraq/Syria (which attacked Paris, Brussels, and San Bernadino), Al-Qaeda central in Afghanistan (which attacked New York City; Washington, DC; London; and Madrid), and ISIS-Libya (which attacked Manchester, England). In short, ISIS-Libya is the only global reach terrorist group operating in Africa.

All other terrorist groups in Africa are essentially local insurgencies with exclusively local interests—they have no intent to attack the United States and hence are no threat to U.S. national security. Nonetheless, U.S. military personnel are engaged in an expansive array of military (including combat) operations across Africa to target these non-threatening terrorist groups. This is the definition of too much force against too little threat.

The second problem is that the United States’s force-based approach to combatting terrorism is arguably helping to make the problem of Islamic terrorism worse, not better. This is especially evident in Africa where current U.S. counterterrorism inadvertently fuels anti-Americanism. It also aids the non-democratic and repressive tendencies of local regimes, which experts find is the primary driver of terrorist recruitment in Africa. As terrorists continue to gain ground in Africa and local African partners become less popular, the dangers of overexpansion and mission creep expand for the United States.

U.S. policy should change. Washington needs to draw down from virtually all African conflict zones, significantly reduce U.S. military bases in Africa, and use force only against global reach terrorists from over-the-horizon.

Contemporary U.S. military activity against terrorism in Africa

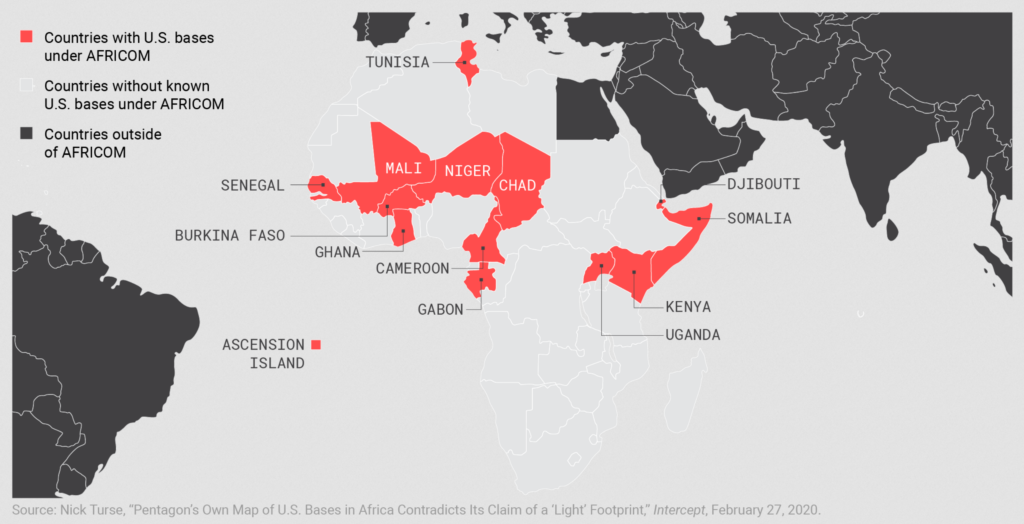

The United States has substantially increased its military presence in Africa since the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Prior to 2006, the United States had no bases or permanent military personnel in Africa. Today, U.S. Africa Command (AFRICOM) has upwards of twenty-nine military bases and outposts across fifteen African nations, according to the most recent data (see figure 1).1

Current data indicates that 6,000 to 7,000 U.S. troops are stationed under AFRICOM. While detailed information on their base locations remains scarce, a 2020 investigative report by journalist Nick Turse, sourced from AFRICOM documents via FOIA, revealed the U.S. maintains over 29 enduring and contingency bases across Africa. This stands as the most recent exhaustive account of U.S. AFRICOM bases.

Official accounts indicate there are roughly 6,500 U.S. troops, civilians, and contractors in Africa under AFRICOM.2 The Department of Defense does not publicly report figures for temporary forces rotating through conflict zones (which tends to push overall numbers higher at any given time) or support personnel for different theaters. Consequently, the United States likely has far more defense personnel in Africa today than the reported number of 6,500.3

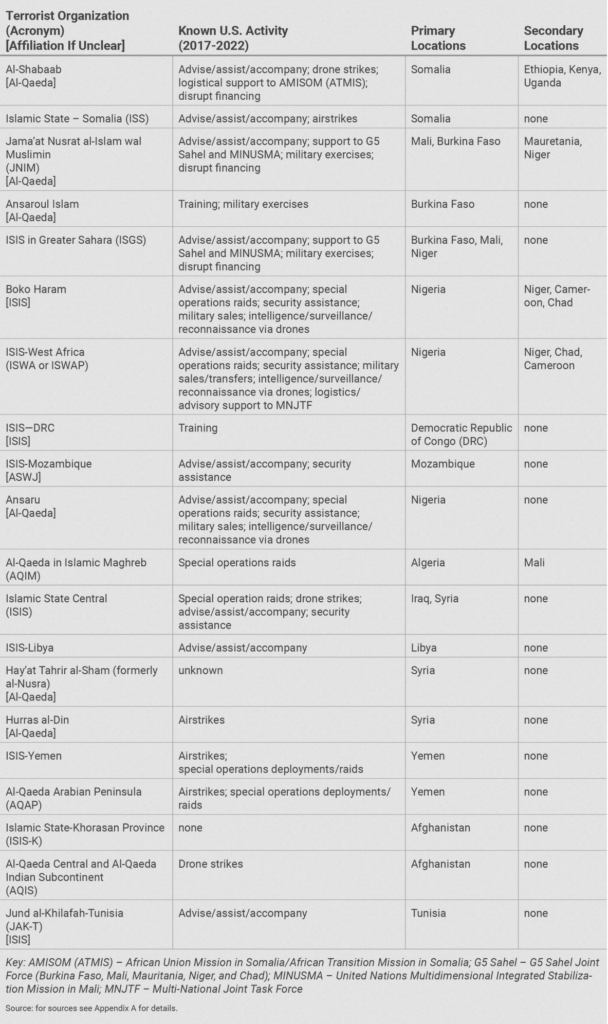

Table 1: Known activity of AFRICOM and CENTCOM against primary terrorist organizations in Africa and the Middle East

As the table shows, the United States is combatting almost two dozen terrorist groups across Africa through air and drone strikes, special forces units, advise, assist, and accompany missions, security aid, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance support.

The number of U.S. special operations forces in Africa has increased significantly over time. In 2006, one percent of all U.S. commandos worldwide were dispatched to Africa. By 2021, that number was fourteen percent, the highest in any region except the Middle East.4 In 2017, one commentator noted that the increase of U.S. commandos in Africa represented “the most dramatic growth in the deployment of America’s elite troops to any region of the globe” over the past fifteen years.5

Defense spending in Africa has increased substantially too. Exact figures here are difficult to come by since publicly available data on spending for AFRICOM is limited.6 We can assume the increase in spending for Africa since the mid-2000s has been significant, however, simply based on the increased numbers of troops, support personnel, and bases in the region. All carry substantial costs.

So, exactly what are U.S. troops doing in Africa? In short, they are fighting terrorist insurgencies to a degree most U.S. citizens are almost certainly unaware of.

Column 2 of table 1 details the types of activities that U.S. military personnel are currently engaged in to counter the most prominent terrorist organizations in Africa and the Middle East. In addition to direct raids, U.S. special operators carry out “training” and 127e “advise/assist/accompany” operations. Congress granted 127e authority after September 11 to develop local proxy armies. In this 127e capacity, U.S. special operators train, accompany, and command those units on missions against local jihadist groups.7

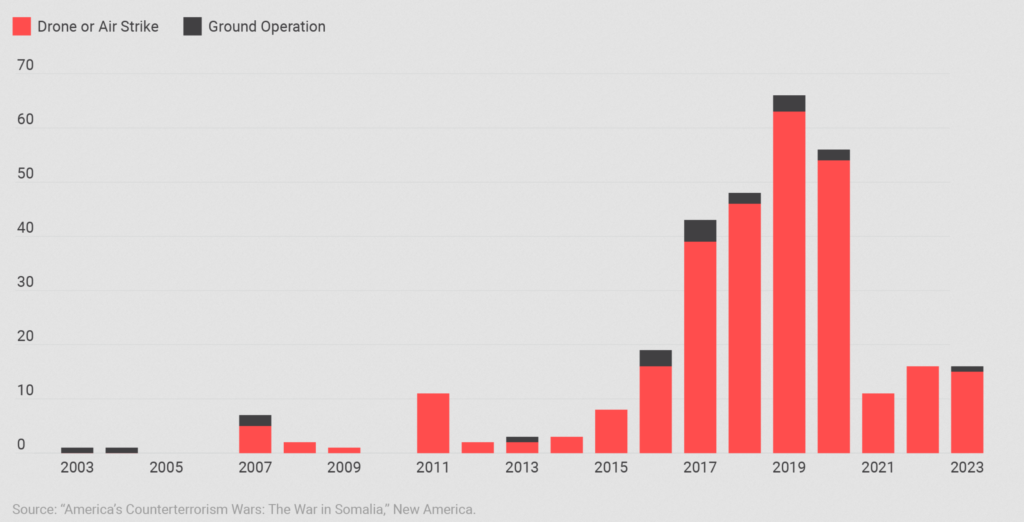

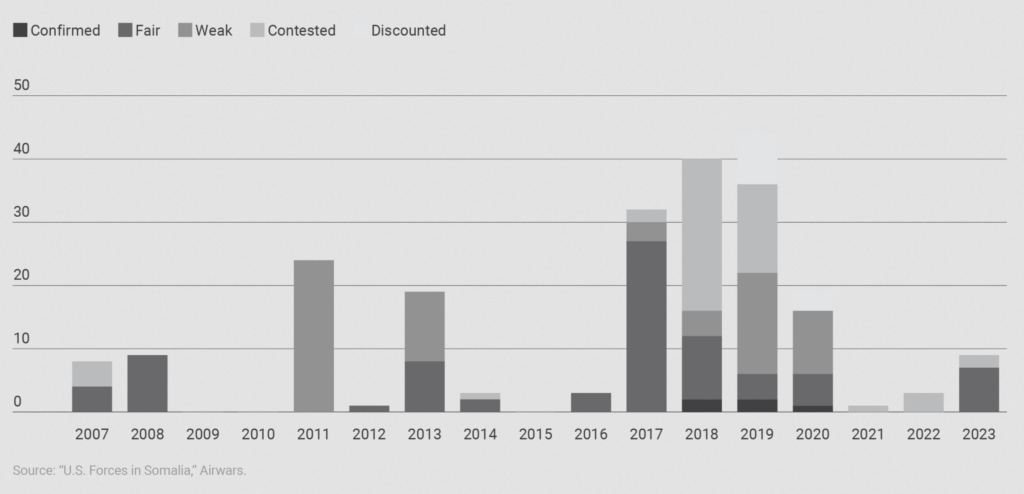

U.S. counterterrorism strikes in Somalia (2003–2023)

Somalia has been a core focus of U.S. counterterrorism efforts, with hundreds of strikes being conducted against Al-Shabaab and Al-Qaeda targets since 2003.

Information on 127e activities is mostly classified and thus limited. Public records on casualties, specific missions conducted, and mission effectiveness are largely unavailable. From what we do know, 127e activities appear significant. One report noted that between 2017 and 2020 alone, U.S. commandos conducted approximately 100 different 127e missions in 20 different African countries.8 Given increased defense budgets and troop levels, the pace of these missions has almost certainly increased in the last three years too—perhaps substantially.

There should be little illusion about what “advise/assist/accompany” means in African conflict zones today: U.S. forces are frequently engaged in combat with few apparent limits. During the late 2010s battle against ISIS in Iraq and Syria, limits set by the Obama administration kept U.S. troops away from the front lines of conflict.9 No such limits appear to exist for U.S. commandos in Africa today. According to a former U.S. defense official in 2021, “combat action” with the potential loss of American lives is “an occupational hazard of partnered operations” in Africa.10

The extent of actual U.S. casualties since the 2000s is unknown because the Department of Defense does not provide that data. Isolated casualty incidents are occasionally reported. The October 2017 Tongo Tongo terrorist attack in Niger is the most publicized recent casualty event. Four U.S. and four Nigerien soldiers died in the attack—reportedly the deadliest single casualty event for the U.S. military in Africa since the “Black Hawk Down” incident in Somalia in 1993.11

Finally, as U.S. troops have become more engaged in ground operations in Africa since 2006, U.S. drone and air strikes against terrorist groups have naturally expanded in kind to support those operations. Most of this activity has come in Somalia and Libya. In Somalia, one recent report notes that since 2007 the United States has conducted “278 declared actions.”12 According to New America, the United States conducted 550 strikes on ISIS targets in Libya between 2011 and 2020.13 Strikes are typically directed by special operators on the ground engaged in search and destroy missions.14

In sum, the United States is deeply engaged in many wars (largely beyond the view of the U.S. public) against Islamist organizations across the African continent today.

Two problems with current U.S. counterterrorism strategy

There are two main problems with contemporary U.S. counterterrorism in Africa. First, threat assessments are inflated, leading to an overcommitment of resources to counterterrorism in Africa. Second, the current strategy is not only ineffective but also counterproductive and risks increased strategic overreach among other dangers.

Threat inflation and excessive force

The 2022 National Security Strategy (NSS) states that the main priority of U.S. counterterrorism policy is to “disrupt and degrade terrorist groups that are plotting attacks against the United States, our people, or our diplomatic and military facilities abroad.”15 This global reach standard for measuring threat is, by and large, the right one. One reason is it fits with public opinion. Research demonstrates that the U.S. public cares most—if not exclusively—about terrorist strikes against the United States and its closest democratic allies, especially in Europe.16 Applying the global reach standard would also prevent overreaction, where too much force is applied against too little threat.

Today’s threat inflation stems from the conventional definition in U.S. policy circles of “global intent” for terrorist groups in Africa and other parts of the world. Specifically, most define “intent” based exclusively upon a group’s affiliation to ISIS central in Syria or Al-Qaeda central in Afghanistan. From Al-Shabab (Al-Qaeda) and Boko Haram (ISIS) to ISIS-K and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, affiliation by local groups to ISIS central or Al-Qaeda central is commonly interpreted to mean that an airtight bond exists between the core and the periphery. In reality, groups affiliate for myriad reasons, many of which are not indicative of a commitment to global jihad.

Affiliation determines intent, according to the conventional wisdom. This leads to two false assumptions. First, since ISIS and Al-Qaeda central want to attack the United States, so do its regional affiliates.17 Second, the danger of Islamic terrorism today remains elevated even though ISIS central and Al-Qaeda central are relatively weak compared to the 2000s and 2010s. Why? Because the affiliates of both ISIS and Al-Qaeda (who again are thought to share an airtight commitment to global strikes with the core) are still active and thriving.

For example, in testimony before Congress in December 2021, the acting principal deputy coordinator at the State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism testified that “foreign terrorist groups remain a persistent threat,” continuing, “ISIS and al-Qaeda remain resilient and determined. Despite significant losses in leadership and territorial control, both groups are leveraging their branches and networks across the Middle East, Asia, and Africa to advance their agendas.”18 A recent American Enterprise Institute report demonstrated the same assumptions, opening with the statement, “Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State are rising in Africa.”19

This conventional logic also helps explain and justify today’s expansive counterterrorism operations in Africa. When local affiliates are understood primarily as carbon copies of ISIS or Al-Qaeda central, the threat of Islamic terrorism is massive—everywhere, in fact. No wonder the United States has boots on the ground fighting terrorists in places like Niger, Somalia, Kenya, and Tunisia today.

A better measure of global intent: Where terrorists strike

Affiliation to ISIS or Al-Qaeda central is a poor measure of a terrorist group’s global intent and, by extension, a poor way to determine whether a group threatens U.S. national security.

History shows that local terrorist organizations typically affiliate to ISIS or Al-Qaeda not because they want to pursue global jihad but to increase their profile, recruit, and raise funds. Many groups targeted by U.S. counterterrorism today chose to affiliate with ISIS and Al-Qaeda at points of desperation when their organizations were struggling to survive. 20 While affiliation has brought some oversight/input from ISIS and Al-Qaeda cores at times in the past, this is much reduced today due to the decimation of the central organizations. 21 In fact, we know that the targeting of ISIS and Al-Qaeda cores has disincentivized many affiliates—some publicly—from endorsing global strikes out of fear of facing similar retribution from the United States and its allies. 22

A better way to measure the global intent of Islamist terrorist organizations is to look not at how groups label themselves but instead at where they target their operations. 23 If a group attacks or attempts to attack the United States and its closest democratic allies, then that group has “global intent” and poses a threat to the United States. By contrast, if a group focuses solely on local targets, it has “local intent” and poses little to no threat to U.S. security. This more discriminating approach recognizes that groups like Boko Haram or Al-Shabaab are brutal and even highly ideological. Yet, it also recognizes that these and many other affiliates are also exclusively local, rooted in and centered around local insurgencies with exclusively local—not global—interests. Groups like Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), Ansaru, and Al-Qaeda Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) solely attack targets, for instance, in West and North Africa, not Europe or the United States. That makes them “local reach” terrorist organizations.

Some in the U.S. government rightly think about global intent in this more discriminating, strike-based way. A former AFRICOM commander labeled Boko Haram an exclusively “local effort” based primarily on where the group targets its operations (i.e., Africa only). 24 Likewise, the U.S. director of national intelligence (DNI) recently concluded that “most of…[Al-Shabab’s] fighters are predominantly interested in the nationalist battle against the Somali government,” not attacking the United States and its allies. 25 In these assessments, intent (and threat to U.S. national security) is determined not by affiliation but by where groups target their activity. This kind of thinking needs to move from the margins to the center of U.S. counterterrorism threat assessments.

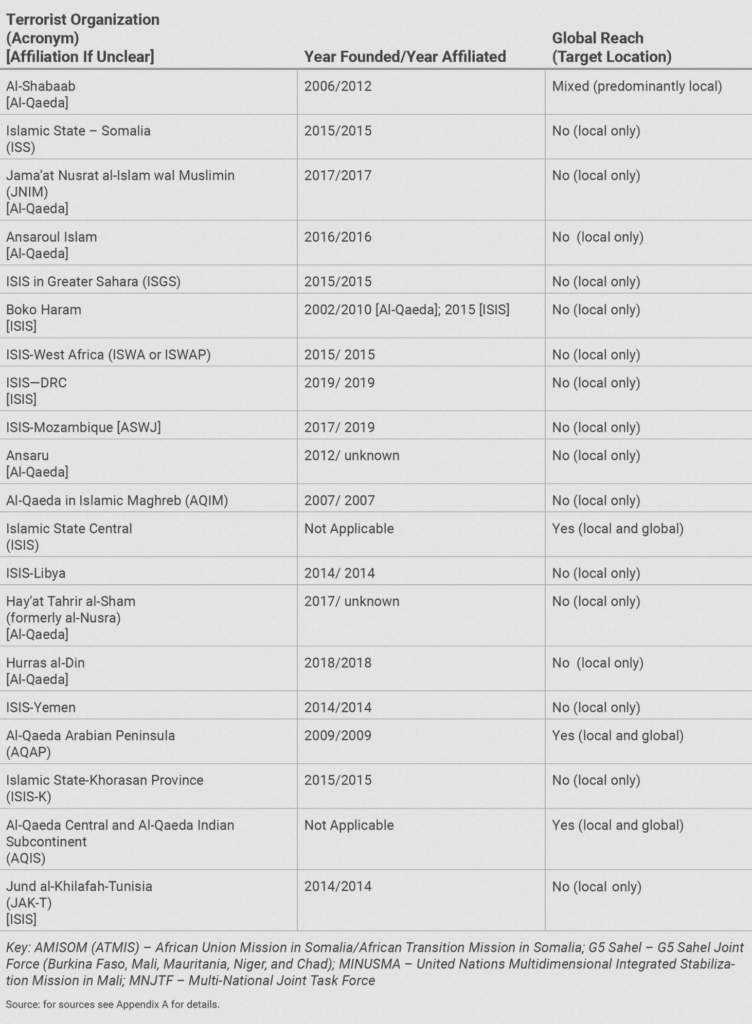

TABLE 2: Date founded and global reach of terrorist groups in Africa and the Middle East

Very few are global reach

Column 3 of table 2 denotes the global reach of the Al-Qaeda and ISIS affiliates targeted by U.S. counterterrorism operations today across the Middle East, South Asia, and Africa.26 Using the above standard of targeting, “intent” is measured by where groups have carried out attacks since September 11 (i.e., United States or European/Asian democracies for “global”).

In short, of the 20 terrorist organizations in table 2, AQAP in Yemen and ISIS-Libya are the only two affiliates of Al-Qaeda central and ISIS central that demonstrate global intent. All others are exclusively local, non-global reach terrorist groups.27

Al-Shabaab attempted to strike the United States in 2017 (a failed airline hijacking). While the attack is an indicator of potential global reach elements within the group, I code Al-Shabaab a “mixed reach” terrorist organization because experts (like the DNI above) tend to consider Al-Shabaab predominantly—if not exclusively—locally focused. Leading Somali specialists argue that if U.S. troops had not been in Somalia, the attempted 2017 strike would not have happened.28 Experts agree that all of Al-Shabaab’s strikes beyond Somalia’s borders come only against states standing in the way of its local, insurgency-based objectives.29 While its potential global nature should not be entirely ignored, the 2017 hijacking attempt falls into this category—tied to Al-Shabaab’s local objectives, not Al-Qaeda central’s ideological goals. Hence, the label “mixed reach,” rather than “global reach,” for Al-Shabaab.

Limited means suppress global reach

The lack of global intent for most groups currently targeted by U.S. counterterrorism is reinforced by a lack of means to carry out global strikes for virtually all these groups, as well. Leading counterterrorism/regional experts note that the affiliates of ISIS and Al-Qaeda centrals in table 2 possess very limited organizational and financial capacity to plan and/or conduct global strikes today.30

Consider the two affiliates—ISIS-Libya and AQAP—that possess global intent, for example. Today, ISIS-Libya is “a shadow if its former self” (100 fighters, at most) due to pressure from international and Libyan military activity.31 Following years of civil war in Yemen, AQAP finds itself in the same position. A 2022 assessment notes that “major defeats” at the hands of local security forces have left AQAP “in shambles.”32 Given these constraints, it is little surprise that attacks by both ISIS-Libya and AQAP have been exclusively local over the last five or six years. This is all these groups can muster given their weakness.33 Resource constraints suppress global intent and reinforce staying local.

In sum, local ISIS and Al-Qaeda affiliates in Africa and many other places are “ISIS” or “Al-Qaeda” in name only. Therefore, they pose little to no direct threat to the United States or its closest democratic allies.

Therein lies the mismatch between means and threats at the heart of U.S. policy today. Given the increasing U.S. military commitment to Africa, more U.S. soldiers are in harm’s way and national resources are on the line against threats that truly aren’t threats. In fact, given the local focus of virtually all these jihadist terrorist organizations, it is most accurate to label much of U.S. activity today across Africa as counterinsurgency, not counterterrorism. In partnering with many local governments, the United States is basically fighting a slew of low-grade wars meant to shore up mostly unstable, non-democratic regimes (like the long U.S. war in Afghanistan) that are often highly unpopular, brutal, and corrupt. In short, U.S. policy in Africa today reflects the classic forever-war recipe of using limited force to achieve goals that appear difficult if not impossible to achieve.

The counterproductive nature of U.S. counterterrorism in Africa

Some may argue that even if the United States is currently doing more than it needs to in Africa against terrorism, it is “better to be safe than sorry,” since a non-global-reach terrorist organization today could go global tomorrow. There are seven major problems with this argument.

First, “better safe than sorry” thinking overestimates the incentives for local terrorists to turn global. While locally focused terrorists could choose to turn global, there is no good theoretical reason for them to do so. Global strikes distract attention and draw resources away from the core founding local interests of groups.

Furthermore, groups that go global are almost guaranteed to draw the ire of the United States and other great powers, which can impact both group survival and again draw attention and resources from core local objectives.

These kinds of disincentives help explain the ongoing local focus of the vast majority of groups in table 2. Column 2 demonstrates the date (if available) that leading Islamist terrorist groups were formed and the date (if available) that those groups affiliated with either Al-Qaeda or ISIS.34 Fourteen of the nineteen affiliates in table 2 were originally formed a decade or more ago, with the other five founded between six and nine years ago. Again, of these affiliates, AQAP and ISIS-Libya are the only two with global intent. All other groups strike only local targets.

It is worth asking: If an affiliate group has not turned to global strikes yet (after years, even a decade or more, in existence), is it reasonable to expect it to ever move in this direction? Unlike the majority of terrorist groups discussed here, Al-Qaeda central and ISIS central were both founded with global ambitions from the beginning and each launched strikes against Western targets soon after their founding (four years for Al-Qaeda, one for ISIS). Likewise, ISIS-Libya’s first (and only) global strike came just over a year after its founding.35

In short, if global intent has not shown up by now for most groups in Table 2, it likely never will. That means continuing U.S. counterterrorism for “better safe than sorry” reasons is a waste of U.S. taxpayer money and military assets at a time when the United States faces other more pressing global challenges.

Second, “better safe than sorry” thinking overlooks the ineffective nature of contemporary U.S. counterterrorism. Leading counterterrorism experts at a 2022 conference hosted by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point used terms like “lackluster,” “harmful at worst,” “unsustainable,” and “ineffective” to describe current U.S. counterterrorism in Africa.36 The numbers bear these assessments out. Since the U.S. started military operations against African jihadists in the mid-2000s, the amount of local terrorist activity and the number of jihadist groups on the continent have exploded. Attacks by Islamic terrorists increased by 22 percent continent-wide last year alone.37 The trend has been especially bad in West Africa, which saw a seven-fold increase in terrorist attacks between 2017 and 2020.38

Third, “better safe than sorry” thinking overlooks the impact of U.S. assistance on coups and violence by local regimes that, in turn, aids terrorist recruitment. According to most experts, the reason for terrorist growth in Africa over the past two decades lies in the failure of autocratic regimes in the region to address the basic needs of their citizens. Recruitment by Islamist groups is “fueled more by hunger, desperation, governance failures, and repressive crackdowns than by fantasies of global Islamist jihad,” notes Herman Cohen, a former assistant secretary of state for African affairs.39 Eight of the governments in West Africa—most of whom partner with the U.S. on counterterrorism operations—rank near the bottom in recent worldwide governance indexes.40 This has made these states fertile ground for jihadists, who recruit on “predatory state actions” and “install themselves as security providers and defenders of vulnerable populations,” according to regional experts.41

With its focus predominantly on direct force, U.S. counterterrorism in Africa inadvertently makes the regime-led violence that fuels terrorist recruitment like this worse, not better. Specifically, U.S. military training and assistance for counterterrorism has had the unintended consequence of enhancing authoritarian rule and repression against civilian populations in parts of Africa.

A recent study found that when foreign military leaders receive training from the United States, the probability of those leaders later carrying out military coups increases significantly.42 We see evidence of this across Africa with U.S. counterterrorism partners. In the last two years, U.S.-trained military leaders in West Africa have carried out or attempted at least eight coups. Included here are U.S. counterterrorism partner states Burkina-Faso, Mali, Niger, and Mauritania in West Africa. One of the leaders (Brigadier General Massou Salaou Barmou) of the July 2023 coup in Niger trained at Fort Benning, Georgia and the National Defense University in Washington, DC.43

This tendency toward coups and repressions is unsurprising. A large body of work points to the ineffective and counterproductive outcomes of training for counterterrorism and other purposes. “Despite committing vast amounts of resources toward foreign military training—including almost $15 billion to train over 2.3 million military students around the world between 1999 and 2016—the United States,” according to Renanah Miles Joyce, a professor at Brandeis University and former analyst at the Department of Defense, “has struggled to produce militaries that are either competent or liberal-minded, especially in weak and unstable states.”44 A core problem here is that interests favored by the United States (i.e., liberal norms, respect for civilian control) are often misaligned with the interests of the militaries that the U.S. trains (i.e., population control, institutional power). U.S.-trained militaries often absorb the skills training well but ignore the values training. Coups like those recently in West Africa sometimes follow.45

In the aftermath of these coups, violence against civilians often soars and terrorist recruitment increases. Mali is a leading example in West Africa. U.S.-trained military leaders took power there in 2020 and more civilians were killed in Mali in every quarter of 2022 than in any previous calendar year. Indeed, fatalities from violence against civilians were seven times higher in 2022 than in 2021. Aided by Russian Wagner forces, much of this violence has come at the hands of the regime.46

Terrorist groups have benefitted from the increased violence. Fueled by new recruitment around regime violence against civilians, militant Islamist attacks have increased a staggering seventy percent in Mali since the 2020 coup.47 In short, U.S. military training has arguably (and, again, inadvertently) exacerbated the problem of Islamic terrorism in Mali and other places across Africa.

Fourth, “better safe than sorry” thinking overlooks the extent to which the misuse of U.S. security assistance by local partners fuels terrorist recruitment. Authoritarian regimes in Africa sometimes siphon U.S. security assistance away from counterterrorism to civilian control and repression.48 A 2023 study found that in Somalia, U.S.-armed and trained contingents of Somali soldiers are regularly diverted from counterterrorism operations by the Somali government to domestic “law enforcement” objectives, like personal protection of political elites, roadblock policing, and attacks on political opponents.49 These kinds of activities aid terrorist recruitment.

The fact that African partners misuse U.S. security assistance for domestic repression is not surprising given what the academic literature shows about client-patron relationships around counterterrorism assistance in Africa (and other places). In short, clients (i.e., U.S. aid recipients) typically resist patron (i.e., U.S.) demands to use aid for patron-designated goals (i.e., fighting terrorists). For reasons of pride, protecting their sovereignty, the socio-cultural structure of militaries, and/or the immediate needs of the regime, clients often deflect aid toward things like regime stability operations that can be especially inhumane.50 Not surprisingly, several studies have shown that U.S. security assistance worldwide in the post–Cold War period has been at best ineffective (thus, wasteful) and, at worst, has inadvertently fueled conflict and repression.51

West Africa offers good examples of this problem. Chad is “an important U.S. partner in the fight against terrorism in the Sahel region,” according to the State Department. In recent years, Chad has received sizable amounts of U.S. military assistance and arms (over $2 million in arms sales and about $4 million in security assistance in 2021/2022).52 In October 2022, the Chadian government massacred 128 pro-democracy protestors. Though not known definitively, U.S. weapons may very well have been used in the massacre.

According to regional expert Alex Thurston, U.S. policymakers tend to look the other way when it comes to incidents such as the massacre in Chad out of fear that the United States could lose influence to other great powers.53 U.S. General Stephen Townsend recently said that U.S. security assistance to West Africa allows the United States to “exploit relationship gaps” in its competition with Russia and China.54 Regardless, past and present U.S. security assistance might be making matters worse when it comes to terrorism in Chad.

Burkina-Faso offers another example. In the name of “fighting terrorism,” the authoritarian government there used past U.S. military assistance to repress the Fulani minority to shore up regime strength. In December 2022, for instance, a Burkinabe militia went house to house in one village and massacred 80 Fulani civilians.55 The Fulani have no natural ties to Islamist terrorist organizations. Regardless, security forces have “a green light to kill anyone they want, without any consequences,” according to one expert.56

This violence (inadvertently aided again by U.S. arms) against the Fulani has backfired. Many Fulani are joining ranks with Islamist groups like JNIM to oppose the Burkinabe regime. Terrorism has soared in Burkina-Faso in recent years. In 2022, Burkina-Faso and Mali accounted for seventy-three percent of terrorism deaths in West Africa. In Burkina-Faso alone, that number had increased by fifty percent from the prior year.57

Overall, while U.S. military assistance is not the main cause of terrorism in Burkina Faso and other places, it is an unintended contributing factor that is making matters worse, not better.58

Fifth, “better safe than sorry” thinking misses the extent to which current U.S. policy aids the growth of anti-Americanism in Africa. Direct U.S. military action in Africa generates anti-Americanism that aids recruitment by Islamist groups and might someday lead to direct attacks on the United States.

Drone strikes can be an effective tactic for disrupting terrorist organizations and operations.59 Unfortunately, U.S. airpower has produced extensive collateral damage over the past decade and a half in Africa. The vast majority of U.S. drone and air strikes in Africa have been in Libya and Somalia. The numbers of civilian deaths from drones in these two countries are murky because of poor reporting by AFRICOM, but reliable estimates put deaths in the thousands.60 Whether this type of collateral damage aids terrorist recruitment is a debatable topic, but it certainly can’t help the U.S. cause.61

Drones aside, the general presence of U.S. forces in Africa has created popular frustration and anger at the United States that, again, inadvertently helps terrorist recruitment. In West Africa, local governments (many of whom ironically partner with the U.S. on counterterrorism) often intentionally fuel this resentment. The Malian government tries, for example, to tap into popular discontentment with France and the United States to deflect blame from itself for the poor living conditions faced by everyday Malians. According to Denis Tull, the regime draws upon “a discourse of international tutelage” to communicate to “skeptical voters that its responsibility for the continuing crisis [in Mali] is limited given the persistence of intrusive foreign [i.e., U.S. and French] intervention.”62

Though anti-French sentiment runs much deeper in West Africa than anti-Americanism, the latter is still there.63 The largest deployment of U.S. forces in West Africa—roughly 800 special operators—is in Niger.64 Leading public figures in Niger claim that the U.S. presence makes things worse, not better. “Are they really here to help our soldiers?” asked Boulama Hamadou Tcherno, a civil society leader in Niger in 2020. “Terrorism has increased since the arrival of U.S. soldiers; in fact, their presence on the ground does not make any changes.”65 On a similar note, Mariama Bayard, leader of the opposition in Niger asserted, “U.S. soldiers are creating a perfect condition for the Sahel to blow up.”66

The U.S. military presence in Somalia has unintentionally helped Al-Shabaab too. Tricia Bacon, a professor at American University and former foreign affairs officer on counterterrorism at the State Department, argues that Al-Shabaab recruitment is aided significantly by foreign intervention, including U.S. forces being on the ground in Somalia. Drawing on a collective Somali identity, the group has made the departure of foreign forces a central component of its messaging and overall agenda.67

This has been the case from the very earliest days of the U.S. effort to counter jihadists in Somalia. After the United States supported the 2006 intervention of Ethiopian forces in Somalia, Roland Marchal found, for instance, that “anti-American sentiment brought the local population together along with its hostility to a series of assassinations and kidnappings of religious figures that were thought to be ordered by the Americans and Ethiopians and carried out by the factions.”68 Bacon also highlights that Al-Shabaab’s enemy image of (and messaging around) the United States intensified dramatically after direct U.S. military intervention in the mid-2010s.69

Sixth, “better safe than sorry” thinking misses the extent to which U.S. military engagement might fuel the next generation of 9/11 terrorists. Coupled with association with repressive African regimes, the U.S. military presence gives “credence to the anti-imperial narratives of African jihadi groups associated with Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State,” according to experts at the 2022 terrorism conference at West Point.70 Some at the conference rightly warned that current U.S. military activity might encourage the growth of the next generation of 9/11-style attackers.71 As noted above, all but one of Africa’s major terrorist organizations is locally focused today. That will likely change if the United States continues to hang around and bomb these groups.

Again, Al-Shabaab offers a classic example. It is a local insurgency that attempted a global strike against the United States because U.S. forces were attacking it. The same scenario could become more widespread, involving not just Al-Shabaab but other African terrorist groups in the future, if U.S. counterterrorism remains on its current course. Like 9/11, the U.S. homeland could easily become a target once more.

Seventh, “better safe than sorry” thinking tends to overlook the danger of mission creep and strategic overstretch. Not only could the United States find itself stuck interminably in stalemated civil wars, but it may also get further dragged into conflicts (by the way, all in the name of fighting non-global-reach terrorists) to prop up increasingly unpopular, nondemocratic partners as they lose domestic support and legitimacy.

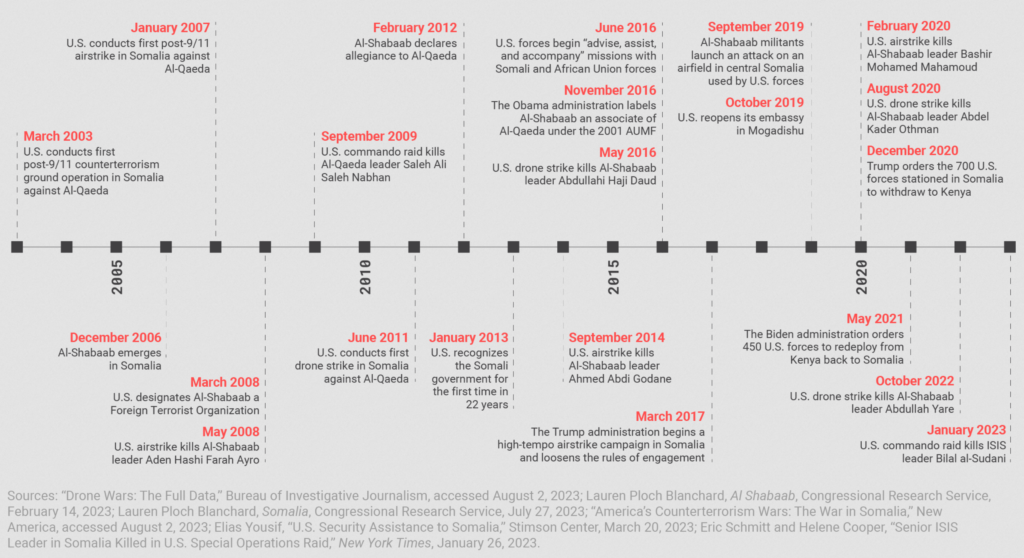

Escalating U.S. involvement in Somalia since 2001

Since the start of the Global War on Terror, Somalia has been a central focus of U.S. counterterrorism efforts with regular strikes against Al-Qaeda and Al-Shabaab leaders.

In many respects, mission creep is already happening: Since 2006 there have been more than 20 new U.S. military bases, expansive use of U.S. airpower, and substantial increases in U.S. military personnel in Africa.

Specific theaters tell a story of mission creep too. U.S. engagement in Somalia started small in the late 2000s with security assistance and training for the Somali army. It ballooned in the 2010s to hundreds of airstrikes, bases in-country, and U.S. special operators deployed on the ground to fight Al-Shabaab directly.72 Likewise, in West Africa, U.S. military engagement started as a refueling mission to support Operation Barkhane, France’s expansive counterterrorism program in the region. Since then, the U.S. presence has expanded substantially to include U.S. troops fighting terrorists in Niger and perhaps other West African countries, expansive drone activity, multiple bases in the region, and training in neighboring states.73

Today, in fact, the potential for additional mission creep and strategic overstretch is probably most acute for the United States in West Africa. Without serious reassessment, the United States could easily be heading toward dramatically increasing troops, drone strikes, training, and the like to prop up unstable, unpopular regimes in this region.

The prelude to U.S. escalation here would likely be the ongoing reduction in France’s role in the region. Based on the same logic as U.S. policy, Operation Barkhane (which formally ended in late 2022) failed. This operation actually fueled strong anti-French sentiment, jihadist growth, and military coups in Mali, Burkina-Faso, and Chad. France has pulled forces back to Niger, where it wants to continue the same policies. Failure will likely follow again (in fact, the 2023 coup in Niger was fueled by anti-French sentiment and increased terrorist activity in Niger).74 Anti-American sentiment will likely continue to grow alongside anti-French sentiment.75

Furthermore, if France follows suit and fully retreats from Niger like it has from Mali and Burkina-Faso, the United States could find itself holding the bag in West Africa.76 Much like the 1954 aftermath of France’s collapse at Dien Bien Phu that brought the United States into Vietnam, U.S. military engagement in West Africa could increase dramatically in future years to pick up the pieces of what France leaves behind. All in the name of fighting terrorist threats to the United States that really aren’t threats to the United States.

In sum, U.S. counterterrorism policy in Africa appears to be doing more harm than good, both for Africans and for U.S. security goals. The misuse of U.S. training and security assistance by many African partners aids illiberalism and terrorist recruitment. The direct use of force by the United States in African conflict zones fuels anti-Americanism and may aid future recruitment of global-reach terrorists. Finally, the dangers of strategic overstretch run high, especially in West Africa.

A better U.S. counterterrorism strategy

Based on the preceding analysis, the U.S. counterterrorism footprint in Africa needs to be significantly revised. There needs to be a rebalancing that focuses appropriate levels of force on real threats while reducing the application of force against local jihadist groups that lack the global reach to threaten the United States.

For starters, force needs to be limited exclusively to global reach terrorist organizations. Preventing attacks from these types of groups is in the U.S. national interest. Military action against non-global-reach terrorists is not. Based upon the above discussion, this means force-based approaches (i.e., direct U.S. military action, security assistance, and training) are currently most appropriate for use against only one terrorist group in Africa: ISIS-Libya.

As a “mixed-reach” terrorist organization, force seems appropriate against Al-Shabaab in the near term as well. Over time (perhaps in conjunction with the African Union’s drawdown of forces by the end of 2024), U.S. forces should leave Somalia, given Al-Shabaab’s predominantly local focus.76 The fact that Al-Shabaab’s one attempted international attack was likely a result of U.S. troop deployment in Somalia suggests U.S. troop removal would turn Al-Shabaab into a locally focused organization. Moreover, the Somali government seemingly cannot win an outright victory, even with U.S. help, as the recent stall in government advances against Al-Shabaab demonstrates.77 Space needs to be made to end the conflict in Somalia, preferably through political reconciliation. A drawdown of foreign, including U.S. forces, could help move that process along.

In targeting global-reach terrorist organizations going forward, the United States should adopt over-the-horizon methods that limit collateral damage. Above all else, this means using light-footprint military operations like special operations raids and drone strikes launched from bases outside a given conflict/target zone. Good recent examples of this include the 2022 U.S. drone strike in Kabul, Afghanistan that killed Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, and the 2023 special operations raid in northern Somalia that killed Bilal al-Sidani, a top operative in ISIS central. Conducted from bases over-the-horizon, both strikes came with no U.S. casualties or collateral damage.79

In recent years, the United States has rightly shifted toward over-the-horizon counterterrorism against ISIS-Libya. A small team (approximately 150) of U.S. special operators are based in Tunisia (i.e., over-the-horizon), where the United States also uses the country’s largest air base near Bizert for drone reconnaissance and, more than likely, strike missions against elements of ISIS-Libya.80 The United States should take a similar approach of over-the-horizon counterterrorism in Somalia. Operations could be conducted primarily from a U.S. base, Camp Lemonnier, in Djibouti.

More still can be done to reduce collateral damage from drones in Libya and other places across Africa. As a good first step, the Biden administration adopted tighter standards for drone strikes last year.81 Those restrictions need to be enforced consistently and extended to collective defense strikes (i.e., strikes called in to support operations in the heat of battle).82

The United States should wind down its force-based operations against all terrorist groups in Africa, besides ISIS-Libya and to some extent Al-Shabaab. This should include phasing out 127e advise/assist/accompany missions and drone strikes in East and West Africa since virtually all current targets of U.S. counterterrorism here are non-global-reach terrorist groups, like JNIM, Boko Haram, and AQIM.

Given U.S. national interests (including great power challenges in Asia), putting U.S. soldiers and military hardware on the line to fight these kinds of groups is not worth the costs. Phasing out direct action may also open the door to a general reduction of U.S. troops and support personnel in Africa.

The United States should consolidate its “lily pad” of approximately 29 bases and outposts across Africa to three, specifically one base for each region (i.e., North, East, and West) where activity by Islamist terrorists is currently most intense.80 These three bases should be used primarily as regional hubs for intelligence gathering, notably to monitor local terrorist groups for any possible transition to global reach.

While military operations based on “better safe than sorry” logic are both overkill and counterproductive, robust intelligence operations based on this logic are not. Intelligence-gathering operations are relatively low-cost undertakings for early detection of new threats that are less likely to fuel terrorist recruitment the way direct U.S. military action does. If the need arises, the regional bases could also be used as staging grounds for any strikes against global-reach terrorists, like the al-Sidani strike in Somalia earlier this year.

In keeping with over-the-horizon counterterrorism, these bases should be located in countries that currently do not face major terrorist activity whenever possible—again, over-the-horizon. This will prevent U.S. forces from coming under undue attack and help avoid mission creep. Some options could include Tunisia and Djibouti in North and East Africa, respectively, and Ghana or Senegal (as opposed to Niger currently, where terrorist activity is especially elevated) in West Africa.

The United States ought to eliminate most security assistance and military training to African countries. It may be difficult to do this in countries hosting U.S. bases—security assistance and training could be the price the United States has to pay, in part, for base access. In the rest of Africa, security assistance should end or, at least be seriously reduced, better tracked, and more tightly conditioned on proper use.

Military training needs to be reduced too. Some argue better training methods—like training senior foreign military officers in the United States—would improve liberal norm diffusion to African militaries. The problem is the United States already does this kind of training and it doesn’t work. For instance, coup leaders in Mali and Burkina Faso were trained on U.S. soil. In short, ending all training makes more sense than maintaining or trying to reform it.

Appendix A

Sources for Tables 1 and 2

Al-Hajj, Taim. The Insurgency of ISIS in Syria. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 15, 2022. https://carnegieendowment.org/sada/86643.

Australian National Security. Islamic State Sinai Province (IS-Sinai). November 29, 2022. https://www.nationalsecurity.gov.au/what-australia-is-doing/terrorist-organisations/listed-terrorist-organisations/islamic-state-sinai-province-(is-sinai).

Blanchard, Lauren Ploch. Al Shabaab. CRS Report No. I10170. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, February 14, 2023. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/IF10170.pdf.

Blanchard, Lauren Ploch. Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently Asked Questions. CRS Report No. R43558. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 29, 2016. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R43558.pdf.

Bureau of Counterterrorism. Country Reports on Terrorism 2020. U.S. Department of State, December 2021. https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2020/.

Byman, Daniel L. Comparing Al Qaeda and ISIS: Different Goals, Different Targets. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, April 29, 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/comparing-al-qaeda-and-isis-different-goals-different-targets/.

Byman, Daniel. L. Hezbollah’s Dilemmas. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, November 2022. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/hezbollahs-dilemmas/.

Carboni, Andrea. The Islamic State in Yemen. Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, April 6, 2023. https://acleddata.com/2018/07/05/the-islamic-state-in-yemen/.

Center for International Security and Cooperation. Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/aqim.

Center for International Security and Cooperation. Ansaroul Islam. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/ansaroul-islam.

Center for International Security and Cooperation. Boko Haram. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/boko-haram.

Center for International Security and Cooperation. Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. Stanford, CA: Stanford University. https://cisac.fsi.stanford.edu/mappingmilitants/profiles/islamic-state-greater-sahara.

Center for Prevention of Conflict. Violent Extremism in the Sahel. Global Conflict Tracker. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, March 27, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel.

Center for Preventive Action. Conflict with Al-Shabaab in Somalia. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, June 30, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/al-shabab-somalia.

Center for Preventive Action. Global Conflict Tracker. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations. June 10, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker.

Center for Preventive Action. Violent Extremism in the Sahel. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, August 10, 2023. https://www.cfr.org/global-conflict-tracker/conflict/violent-extremism-sahel.

Combating Terrorism Center at West Point. June 12, 2022. https://ctc.westpoint.edu/.

Council on Foreign Relations. 2004–2022: Al-Shabaab in East Africa. New York, NY: https://www.cfr.org/timeline/al-shabaab-east-africa.

Council on Foreign Relations. Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP). New York, NY: June 19, 2015. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula-aqap.

Counter Extremism Project. AQAP (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula). New York, NY: June 23, 2022. https://www.counterextremism.com/threat/aqap-al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula.

Federation of American Scientists. Congressional Research Service Reports on Terrorism. April 11, 2023. https://sgp.fas.org/crs/terror/index.html.

Filiu, Jean-Pierre. Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb: Algerian Challenge or Global Threat? Middle East Program, No. 104. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2009. https://carnegieendowment.org/files/al-qaeda_islamic_maghreb.pdf.

Ghanem, Dalia, and Djallil Lounnas. The Last Emir?: AQIM’s Decline in the Sahel. Washington, DC: Middle East Institute, December 7, 2020. https://www.mei.edu/publications/last-emir-aqims-decline-sahel.

Gibbons-Neff, Thomas, and Julian E. Barnes. “U.S. Military Calls ISIS in Afghanistan a Threat to the West. Intelligence Officials Disagree.” New York Times, August 2, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/08/02/world/middleeast/isis-afghanistan-us-military.html.

Hamming, Tore, and Colin P. Clarke. “Over-the-Horizon is Far Below Standard,” Foreign Policy, January 5, 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/05/over-the-horizon-biden-afghanistan-counter-terrorism/.

Hartig, Luke, and Oona A. Hathaway. “Still at War: The United States in Yemen.” Just Security, March 24, 2022. https://www.justsecurity.org/80806/still-at-war-the-united-states-in-yemen/.

Husted, Tomás F. Boko Haram and the Islamic State West Africa Province. CRS Report No. IF10173. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, February 24, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10173.

Institute for Economics and Peace. Global Terrorism Index, 2023: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism. Sydney, AU: March 2023. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.

International Crisis Group. Yemen’s Al-Qaeda: Expanding the Base. Washington, DC: February 2, 2017. https://www.crisisgroup.org/middle-east-north-africa/gulf-and-arabian-peninsula/yemen/174-yemen-s-al-qaeda-expanding-base.

ISS Regional Office for West Africa, the Sahel and the Lake Chad Basin. The Resurgence of Boko Haram’s Breakaway Faction, with its Al-Qaeda Backing, Threatens National and Regional Security. Pretoria, South Africa: Institute for Security Studies, June 1, 2022. https://issafrica.org/iss-today/ansarus-comeback-in-nigeria-deepens-the-terror-threat.

Joscelyn, Thomas. “Al Qaeda and Allies Announce ‘New Entity’ in Syria.” Foundation for the Defense of Democracy’s Long War Journal, January 28, 2017. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/01/al-qaeda-and-allies-announce-new-entity-in-syria.php.

Klobucista, Claire, Jonathan Masters, and Mohammed Aly Sergie. Al-Shabaab. New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, December 6, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/al-shabaab.

Levy, Ido. Egypt’s Counterinsurgency Success in Sinai. Washington, DC: Washington Institute for Near East Policy, December 9, 2021. https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/egypts-counterinsurgency-success-sinai.

Mahtani, Dino, Nelleke van de Walle, Piers Pigou, and Meron Elias. Understanding the New U.S. Terrorism Designations in Africa. Washington, DC: International Crisis Group, March 18, 2021. https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/understanding-new-us-terrorism-designations-africa.

Miller, Aaron David. What the Al-Qaeda Drone Strike Reveals About U.S. Strategy in Afghanistan. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, August 2, 2022. https://carnegieendowment.org/2022/08/02/what-al-qaeda-drone-strike-reveals-about-u.s.-strategy-in-afghanistan-pub-87616.

Mir, Asfandyar. The ISIS-K Resurgence. Washington, DC: Wilson Center, October 8, 2021. https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/isis-k-resurgence.

Morgan, Wesley. “Behind the Secret U.S. War in Africa.” Politico, July 2, 2018. https://www.politico.com/story/2018/07/02/secret-war-africa-pentagon-664005.

National Counterterrorism Center. “Hurras Al-Din.” Counterterrorism Guide. Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, August 2022. https://www.odni.gov/nctc/ftos/hurras_fto.html.

National Counterterrorism Center. “ISIS-Democratic Republic of the Congo.” Counterterrorism Guide. Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, February 2022. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/isis_drc_fto.html.

National Counterterrorism Center. “ISIS-Somalia.” Counterterrorism Guide. Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, September 2022. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/isis_somalia_fto.html.

National Counterterrorism Center. “ISIS-West Africa.” Counterterrorism Guide. Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, September 2022. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/isis_west_africa_fto.html.

National Counterterrorism Center. “Jama’at Nusrat Al-Islam Wal-Muslimin (JNIM).” Counterterrorism Guide. Washington, DC: Office of the Director of National Intelligence, October 2022. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/ftos/jnim_fto.html.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Terrorist Groups: Africa. Washington, DC: National Counterterrorism Center. https://www.dni.gov/nctc/groups.html#africa.

Office of the Director of National Intelligence. 2023 Annual Threat Assessment of the U.S. Intelligence Community. Washington, DC: March 8, 2023. https://www.dni.gov/index.php/newsroom/reports-publications/reports-publications-2023/item/2363-2023-annual-threat-assessment-of-the-u-s-intelligence-community.

Organization for World Peace. Islamic State in Somalia. August 10, 2022. https://theowp.org/crisis_index/islamic-state-in-somalia/

Robinson, Kali. What Is Hezbollah? New York, NY: Council on Foreign Relations, May 25, 2022. https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-hezbollah.

Savell, Stephanie. United States Counterterrorism Operations, 2018-2020. Costs of War Project. Providence, RI: Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, February 2021. https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/papers/2021/USCounterterrorismOperations.

Schmitt, Eric, and Helene Cooper. “Al-Zawahri’s Death Puts the Focus Back on Al Qaeda.” New York Times, August 2, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/02/us/politics/al-qaeda-terrorism-isis.html.

Shaikh, Shaan, and Ian Williams. Hezbollah’s Missiles and Rockets. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 5, 2018. https://www.csis.org/analysis/hezbollahs-missiles-and-rockets.

Thomas, Clayton. Al Qaeda: Background, Current Status, and U.S. Policy. CRS Report No. IF11854. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11854.

Thomas, Clayton. The Islamic State. CRS Report No. IF10328. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10328.

Thomas, Clayton. Terrorist Groups in Afghanistan. CRS Report No. IF10604. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF10604.

Thompson, Jared. Examining Extremism: Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 22, 2021. https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-islamic-state-greater-sahara.

Thompson, Jared. Examining Extremism: Jama’at Nasr Al-Islam Wal Muslimin. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, July 15, 2021. https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism/examining-extremism-jamaat-nasr-al-islam-wal-muslimin.

Thrall, Trevor A., and Jordan Cohen. 2021 Arms Sales Risk Index. Washington, DC: Cato Institute, January 18, 2022. https://www.cato.org/study/2021-arms-sales-risk-index.

Transnational Threats Project. Examining Extremism. Report series. Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2023. https://www.csis.org/blogs/examining-extremism.

Transnational Threats Project. Hay’at Tahrir Al-Sham (HTS). Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2018. https://www.csis.org/programs/transnational-threats-project/past-projects/terrorism-backgrounders/hayat-tahrir-al-sham.

Transnational Threats Program. Jama’at Nasr Al-Islam Wal Muslimin (JNIM). Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2018. https://www.csis.org/programs/transnational-threats-project/jamaat-nasr-al-islam-wal-muslimin-jnim.

Turse, Nick. “New Report Sheds Light on Pentagon’s Secret Wars Playbook.” Intercept, November 3, 2022. https://theintercept.com/2022/11/03/us-military-secret-wars/.

United Nations Security Council. Jund Al-Khilafah in Tunisia. New York, NY: December 30, 2021. https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/jund-al-khilafah-tunisia.

U.S. Department of State. “Country Reports on Terrorism 2020: Egypt.” Washington, DC, https://www.state.gov/reports/country-reports-on-terrorism-2020/egypt/.

Vision of Humanity. Global Terrorism Index. New York, NY: Institute for Economics & Peace. January 10, 2023. https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.

Vohra, Anchal. “ISIS Can’t Even Direct Lone-Wolf Attacks Anymore.” Foreign Policy, April 26, 2022. https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/04/26/the-islamic-state-cant-even-pull-off-lone-wolf-attacks-anymore.

Weiss, Caleb. “Ansaru Reaffirms its Allegiance to Al Qaeda.” Foundation for the Defense of Democray’s Long War Journal, January 2, 2022. https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2022/01/ansaru-reaffirms-its-allegiance-to-al-qaeda.php.

Zenn, Jacob, and Caleb Weiss. “Ansaru Resurgent: The Rebirth of Al-Qaeda’s Nigerian Franchise.” Perspectives on Terrorism 15, no. 5 (October 2021): 46–58. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27073436.

Endnotes

1 On bases, see Chinedu Okafor, “5 African Countries with U.S. Military Bases, Weapons Systems and Troops,” Business Insider Africa, October 5, 2022, https://africa.businessinsider.com/local/leaders/5-african-countries-with-us-military-bases/1n7xsm2; Nick Turse, “Pentagon’s Own Map of U.S. Bases in Africa Contradicts Its Claim of ‘Light’ Footprint,” Intercept, February 27, 2020, https://theintercept.com/2020/02/27/africa-us-military-bases-africom/. Though locations are publicly unknown, a few bases have been closed and new ones opened since 2019.

2 Jeff Schogol, “U.S. Troops are Quietly Helping Fight ISIS, al-Qaida in West Africa,” Task & Purpose, April 3, 2023, https://taskandpurpose.com/news/us-military-west-africa/.

3 The “tooth-to-tail” ratio (T3R) of support to military personnel is generally about 8 to 1, with that ratio even higher in terms of support personnel for more elite forces in the Special Operations Command (SOCOM) and Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), according to a former senior defense official (interviewed, June 17, 2023). See also John J. McGrath, The Other End of the Spear: The Tooth-to Tail Ratio (T3R) in Modern Military Operations (Fort Leavenworth, KN: Combat Studies Institute Press, 2007).

4 Nick Turse, “The U.S. is Losing Yet Another ‘War on Terror,’” Rolling Stone, October 17, 2022, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/war-or-terror-africa-sahel-niger-pentagon-1234612083/.

5 Nick Turse, “The U.S. Is Waging a Massive Shadow War in Africa, Exclusive Documents Reveal,” Vice, May 18, 2017, https://www.vice.com/en/article/nedy3w/the-u-s-is-waging-a-massive-shadow-war-in-africa-exclusive-documents-reveal.

6 Eniola Anuoluwapo Soyemi, Making Crisis Inevitable: The Effects of U.S. Counterterrorism Training and Spending in Somalia, Costs of War Project (Providence, RI: Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, April 27, 2023), 13, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2023/Soyemi_Costs%20of%20War_CTSomalia.pdf; Eniola Anuoluwapo Soyemi, “Making Crisis in Somalia Inevitable: A Roundtable Discussion,” (unpublished discussion at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, Providence, RI, June 14, 2022).

7 “127e” reflects the U.S. Code citation—10 U.S.C. §127e—that grants this authority. International Crisis Group, Overkill: Reforming the Legal Basis for the U.S. War on Terror (Washington, DC: September 17, 2021), 12, https://www.crisisgroup.org/united-states/005-overkill-reforming-legal-basis-us-war-terror; Nick Turse and Alice Speri, “How the Pentagon Uses a Secretive Program to Wage Proxy Wars,” Intercept, July 1, 2022, https://theintercept.com/2022/07/01/pentagon-127e-proxy-wars/; Nick Turse and Sean D. Naylor, “Revealed: The U.S. Military’s Operations in Africa,” Yahoo! News, April 17, 2019, https://www.yahoo.com/now/revealed-the-us-militarys-36-codenamed-operations-in-africa-090000841.html; Sean D. Naylor, “Inside the Pentagon’s Manhunting Machine,” Atlantic, August 28, 2015, https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/08/jsoc-manhunt-special-operations-pentagon/402652/.

8 Turse, “The U.S. is Waging a Massive Shadow War in Africa, Exclusive Documents Reveal.”

9 Michael R. Gordon, Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump (New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2022), 91–92, 112–114, 127–130, 320–328.

10 International Crisis Group, Overkill, 19.

11 Thomas Gibbons-Neff, “An Operation in Niger Went Fatally Awry. Who Is the Army Punishing?” New York Times, November 3, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/03/world/middleeast/army-niger-members-punished.html.

12 “U.S. Forces in Somalia,” Airwars, June 18, 2023, https://airwars.org/conflict/us-forces-in-somalia/. Included are strikes by “drones, AC-130 gunships, attack helicopters, naval bombardments, and cruise missiles.”

13 “Air Strikes, Proxy Warfare, and Civilian Casualties in Libya,” New America, May 26, 2020, https://www.newamerica.org/international-security/reports/airstrikes-proxy-warfare-and-civilian-casualties-libya/glossary-of-belligerents/.

14 Daniel Byman and Ian A. Merritt, “The New American Way of War: Special Operations Forces in the War on Terrorism,” Washington Quarterly 41, no. 2 (Summer 2018): 84, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0163660X.2018.1484226.

15 The White House, National Security Strategy (Washington, DC: October 12, 2022), 31, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

16 C. William Walldorf, Jr., “Narratives and War: Explaining the Length and End to U.S. Military Operations in Afghanistan,” International Security 47, no. 1 (Fall 2022): 93–138.

17 For example, Examining the Worldwide Threat of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Other Foreign Terrorist Organizations: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on National Security of the Committee of Oversight and Reform, House of Representatives, 117 Cong. 1 (2021), https://docs.house.gov/meetings/GO/GO06/20211207/114288/HHRG-117-GO06-20211207-SD003.pdf.

18 Examining the Worldwide Threat of Al Qaeda, ISIS, and Other Foreign Terrorist Organizations.

19 Emily Estelle Perez, The Underestimated Insurgency, Continued: Salafi-Jihadi Capabilities and Opportunities in Africa (Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, December 12, 2022), 1, https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/the-underestimated-insurgency-continued-salafi-jihadi-capabilities-and-opportunities-in-africa/.

20 Ali Soufan, Anatomy of Terror: From the Death of bin Laden to the Rise of the Islamic State (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co., 2017), 199. AQIM offers a good example.

21 Osama bin-Laden struggled to get affiliates to prioritize global strikes. See Soufan, Anatomy of Terror, 22–24, 44, 182–3.

22 Soufan, Anatomy of Terror, 216; Ricardo Rene Laremont, “Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb,” African Security 4, no. 4 (October–December 2011): 244–47, 255–56. See examples from Al-Nusra and AQIM.

23 Barak Mendelsohn and Colin Clarke, “Al-Qaeda is Being Hollowed to Its Core,” War on the Rocks, February 24, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/02/al-qaeda-is-being-hollowed-to-its-core/; Dan Byman, “Why Drones Work: The Case for Washington’s Weapon of Choice,” Foreign Affairs 92, no. 4 (July/August 2013): 42–43; Jason Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa, 2001-2021: Summary Document of CTC’s Africa Regional Workshop,” (workshop, Combating Terrorism Center, West Point, NY, February 4, 2022), 5, https://ctc.westpoint.edu/assessing-u-s-counterterrorism-in-africa-2001-2021-summary-document-of-ctcs-africa-regional-workshop/; Daniel Byman and Asfandyar Mir, “Assessing al-Qaeda: A Debate,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, May 11, 2022: 13–14, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1057610X.2022.2068944?journalCode=uter20.

24 Cited in Lauren Ploch Blanchard, Nigeria’s Boko Haram: Frequently Asked Questions, CRS Report No. R43558 (Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service, March 29, 2016), 6, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/row/R43558.pdf.

25 National Counterterrorism Center, “Al Shabaab,” Office of the Director of National Intelligence, https://www.dni.gov/nctc/groups/al_shabaab.html.

26 The list of affiliates in table 2 matches that in table 1. The list includes all known groups that the United States is targeting today, which in turn represent the highest priorities for U.S. policymakers. The number of sources consulted to collect data for table 2 is extensive. A sample of the major sources can be found at the end of the table. For complete list, contact the author.

27 AQAP, 2015 Charlie Hebdo attack (Paris) and others (2009, 2010); ISIS-Libya, 2017 Manchester, England.

28 U.S. Department of Justice, “Kenyan National Indicted for Conspiring to Hijack Aircraft on Behalf of the al Qaeda-Affiliated Terrorist Organization Al Shabaab,” press release, December 16, 2020, https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/kenyan-national-indicted-conspiring-hijack-aircraft-behalf-al-qaeda-affiliated-terrorist; “AQAP (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula),” Counter Extremism Project, https://www.counterextremism.com/threat/aqap-al-qaeda-arabian-peninsula; Katherine Zimmerman, “No Competition Without Presence: Should the U.S. Leave Africa?” Prism 9, no. 1 (October 21, 2020): 81; Tricia Bacon, Inside the Minds of Somalia’s Ascendant Insurgents: An Identity, Mind, Emotions and Perceptions Analysis of Al-Shabaab (Washington, DC: George Washington University Program on Extremism, Nexus, 2022): 22–23, 88; Soufan, Anatomy of Terror, 196–98; Mohammed Ibrahim Shire, “Now is the Time to Engage Al-Shabaab,” War on the Rocks, October 19, 2021, https://warontherocks.com/2021/10/now-is-the-time-to-engage-al-shabaab-religious-leaders-and-clan-elders-can-help/.

29 Bacon, Inside the Minds of Somalia’s Ascendant Insurgents, 22-23, 88; Claire Klobucista, Jonathan Masters, and Mohammed Aly Sergie, “Backgrounder: Al-Shabaab,” Council on Foreign Relations, December 6, 2022, https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/al-shabaab; International Crisis Group, Considering Political Engagement with Al-Shabaab in Somalia (Washington, DC: June 21, 2022), 21, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/horn-africa/somalia/309-considering-political-engagement-al-shabaab-somalia. For a good detailing of attacks against countries/forces fighting in Somalia, see Luke Hartig and Oona A. Hathaway, “Still at War: The United States in Yemen,” Just Security, March 24, 2022, https://www.justsecurity.org/80806/still-at-war-the-united-states-in-yemen/; Shire, “Now is the Time to Engage Al-Shabaab.”

30 A recent report calculates that “global terror attack capability” is at most “moderate” for a few African affiliates and “low” for all others. Perez, The Underestimated Insurgency, 6.

31 Kathryn Tyson, “Salafi Jihadi Areas of Operation in Libya,” Critical Threats, October 12, 2022, https://www.criticalthreats.org/analysis/salafi-jihadi-areas-of-operation-in-libya.

32 Hartig and Hathaway, “Still at War”; Byman and Mir, “Assessing al-Qaeda,” 7. See also “Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula,” Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, April 6, 2023, https://acleddata.com/2023/04/06/al-qaeda-in-the-arabian-peninsula-sustained-resurgence-in-yemen-or-signs-of-further-decline/.

33 Scholars find that the decentralization of authority/activity to the affiliates that has come with the weakening of ISIS and Al-Qaeda centrals disincentives affiliates from going global as a well. See Barak Mendelsohn, “Bound to Fail: Transnational Jihadism and the Aggregation Problem,” War on the Rocks, August 28, 2018, https://warontherocks.com/2018/08/bound-to-fail-transnational-jihadism-and-the-aggregation-problem/; Barak Mendelsohn, Jihadism Constrained: The Limits of Transnational Jihadism and What It Means for Counterterrorism (New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2018).

34 Some groups changed their name at affiliation, a few were born at affiliation, and others (like JNIM) comprise multiple locally focused groups who merged at affiliation. In the latter, table 2 notes the earliest date among the collection of founding organizations.

35 For al-Qaeda, World Trade Center bombing (1992); for ISIS, Jewish Museum of Belgium (2014); for ISIS-Libya, Manchester bombing (2017); Soufan, Anatomy of Terror, 191–95. AQAP’s leadership hailed directly from Al-Qaeda central in Afghanistan, making it a direct appendage of Al-Qaeda central in ways other affiliates are not (i.e., more global from the start). AQAP’s first global strike came in 2009, the year of its founding.

36 Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa,” 1. For similar assessments, see Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, Preventing Extremism in Fragile States: A New Approach (Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace, February 26, 2019), 8, https://www.usip.org/publications/2019/02/preventing-extremism-fragile-states-new-approach.

37 “Fatalities from Militant Islamist Violence in Africa Surge by Nearly 50 Percent,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 6, 2023, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/fatalities-from-militant-islamist-violence-in-africa-surge-by-nearly-50-percent/.

38 Stephanie Savell, The Costs of United States’ Post-9/11 ‘Security Assistance’: How Counterterrorism Intensified Conflict in Burkina-Faso, Costs of War Project (Providence, RI: Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, March 4, 2021), 3, https://watson.brown.edu/costsofwar/files/cow/imce/papers/2021/Costs%20of%20Counterterrorism%20in%20Burkina%20Faso_Costs%20of%20War_Savell.pdf. See also, Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa,” 1–5.

39 Herman J. Cohen, The Time is Right for a U.S. Pivot to Africa (Philadelphia, PA: Foreign Policy Research Institute, November 18, 2021), https://www.fpri.org/article/2021/11/the-time-is-right-for-a-u-s-pivot-to-africa/.

40 Joshua Meservey, Towards Salafism and Its Implications for Regional Terrorism (Washington, DC: Heritage Foundation, September 24, 2021), https://www.heritage.org/africa/commentary/sahelian-islams-shift-towards-salafism-and-its-implications-regional-terrorism.

41 Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa,” 5–6. See also Perez, The Underestimated Insurgency, 20; Savell, The Costs United States’ Post-9/11 ‘Security Assistance,’ 24.

42 Jesse Dillon Savage and Jonathan D. Caverley, “When Human Capital Threatens the Capitol: Foreign Aid in the Form of Military Training and Coups,” Journal of Peace Research 54, no. 4 (July 2017): 542–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022343317713557.

43 Nick Turse, “Niger Coup Leaders Joins Long Line of U.S.-trained Mutineers,” Intercept, July 27, 2023, https://theintercept.com/2023/07/27/niger-coup-leader-us-military/; Nick Turse, “How Many More Governments Will American-Trained Soldiers Overthrow?” Rolling Stone, February 25, 2023, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-features/west-africa-coup-american-trained-soldier-1234657139/. Michael M. Phillips, “In Africa, U.S.-Trained Militaries are Ousting Civilian Governments in Coups,” Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/in-africa-u-s-trained-militaries-are-ousting-civilian-governments-in-coups-11649505601; Ted Galen Carpenter, “The U.S. Military is Training Third World Coup Leaders Again,” Cato Institute, April 19, 2022, https://www.cato.org/commentary/us-military-training-third-world-coup-leaders-again; Ted Galen Carpenter, “The U.S. Military is Training Third World Coup Leaders Again,” Cato Institute, April 19, 2022, https://www.cato.org/commentary/us-military-training-third-world-coup-leaders-again.

44 Renanah Miles Joyce, “Rethinking How the United States Trains Foreign Militaries,” Lawfare, August 14, 2022, https://www.lawfareblog.com/rethinking-how-united-states-trains-foreign-militaries. On the failure of training to produce liberal norm diffusion, see Renanah Miles Joyce, “Soldiers’ Dilemma: Foreign Military Training and Liberal Norm Conflict,” International Security 46, no. 4 (2022): 48–90; Emily Knowles and Jahara Matisek, “Is Human Rights Training Working with Foreign Militaries? No one Knows and That’s O.K.,” War on the Rocks, May 12, 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/05/is-human-rights-training-working-with-foreign-militaries-no-one-knows-and-thats-o-k/. See also Mara Karlin, “Why Military Assistance Programs Disappoint,” Foreign Affairs 96, no. 6 (November/December 2017): 111–120; Rachel Tecott, “Why America Can’t Build Allied Armies,” Foreign Affairs, August 26, 2021, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-08-26/why-america-cant-build-allied-armies.

45 Stephen Biddle, “Building Security Forces & Stabilizing Nations: The Problem of Agency,” International Security 146, no. 4 (2018): 126–38.

46 “Malian Military Junta Scuttled Security Partnerships While Militant Violence Surges,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, February 27, 2023, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/mali-military-junta-scuttles-security-partnerships-while-militant-violence-surges/#:~:text=Civilians%20have%20borne%20the%20brunt,in%202022%20than%20in%202021; Sam Mednick, “Violence Soars in Mali in the Year after Russians Arrive,” Associated Press, January 14, 2023, https://apnews.com/article/politics-mali-government-russia-violence-10ba966bceb2dc732cb170b16258e5a6. Wagner forces target civilians at uniquely high rates in Africa, accounting for 40 percent of civilian deaths in Mali in 2022.

47 “Debunking the Malian Junta’s Claims,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 12, 2022, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/debunking-the-malian-juntas-claims/.

48 Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa,” 1; Task Force on Extremism in Fragile States, Preventing Extremism, 8.

49 Soyemi, Making Crisis Inevitable, 7.

50 Denis M. Tull, “Rebuilding Mali’s Army: The Dissonant Relationship Between Mali and Its International Partners,” International Affairs 95, no. 2 (1995): 405–22; Niagale Bagayoko, “Explaining the Failure of Internationally-supported Defence and Security Reforms in Sahelian States,” Conflict, Security & Development 22, no. 3 (2022): 243–69; Patricia L. Sullivan, “Lethal Aid and Human Security: The Effects of US Security Assistance on Civilian Harm in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries,” Conflict Management and Peace Studies 40, no. 5 (February 2023 online), https://doi.org/10.1177/07388942231155161. States with weak institutional controls (like autocratic regimes) more often use aid for domestic repression and regime stability.

51 Stephen Wats et al., Building Security in Africa (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2018), https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2400/RR2447/RAND_RR2447.pdf; Karlin, “Why Military Assistance Programs Disappoint”; Patricia L. Sullivan, “Do No Harm: US Aid to Africa and Civilian Security,” Political Violence at a Glance, May 8, 2023, https://politicalviolenceataglance.org/2023/05/08/do-no-harm-us-aid-to-africa-and-civilian-security/.

52 U.S. Department of State, “Integrated Country Strategy: Chad,” May 16, 2022, 1, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/ICS_AF_Chad_Public.pdf; Olivier Guiryanan, “Counterterrorism Assistance to Chad for the Sahel: The Price the People Pay,” Just Security, September 2, 2020, https://www.justsecurity.org/72199/counterterrorism-assistance-to-chad-for-the-sahel-the-price-the-people-pay/; “United States Security Cooperation,” Center for International Policy, https://securityassistance.org/map/.

53 Alex Thurston, An Alternative Approach to U.S. Sahel Policy (Washington, DC: Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft, November 2, 2022): 7–10, https://quincyinst.org/report/an-alternative-approach-to-u-s-sahel-policy/#executive-summary. Warner, “Assessing U.S. Counterterrorism in Africa,” 13.

54 Cited in Thurston, An Alternative Approach to U.S. Sahel Policy, 22.

55 “Burkina Faso: Perpetrators of Nouna Killings Must Face Justice,” Amnesty International, January 10, 2023, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/01/burkina-faso-perpetrators-of-nouna-killings-must-face-justice/.

56 Savell, The Costs of United States’ Post-9/11 ‘Security Assistance’, 17.

57 James Courtright, “Ethnic Killings by West African Armies are Undermining Regional Security,” Foreign Policy, March 7, 2023, https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/03/07/mali-burkina-faso-fulani-ethnic-killings-by-west-african-armies-are-undermining-regional-security/; Institute for Economics and Peace, Global Terrorism Index, 2023: Measuring the Impact of Terrorism (Sydney, AU: March 2023), 2, https://www.visionofhumanity.org/maps/global-terrorism-index/#/.