The continued instability in the global oil market will not only strengthen the unity between the key OPEC+ players but also force them to focus primarily on ensuring their own interests, before taking those of their consumers into consideration.

The last two meetings of OPEC+ — a grouping of the 13 members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and 10 non-OPEC petroleum producers (most notably Russia) — generated some intrigue. The Aug. 3 decision by the expanded cartel to formally increase production in September by 100,000 barrels per day (bpd) and the subsequent decision, during the Sept. 5 meeting, to reduce its output by the same volume raised many questions, including, foremost, what exactly OPEC+ was trying to say. From a practical point of view, these minor increases and reductions had no significance for changing the real balance of supply and demand. In other words, they constituted a political message. However, a message to whom? Most analysts view the situation through the prism of the ongoing Russian war in Ukraine and Western discontent with high oil prices. Partially, they see the cartel’s behavior as an attempt by the Gulf countries (first of all, Saudi Arabia) to balance between Russia and the United States: Initially Saudi Arabia tried to listen to the U.S. demands to raise output, then it changed its mind and reduced it, obviously doing a favor for Russia. Others claim that it was a kind of slap in the face to U.S. President Joe Biden from the Gulf monarchies, dissatisfied with Washington’s changing role in the region. Such explanations are not baseless, but it seems that the truth is much simpler: Under current market conditions, it is unreasonable for OPEC to make sharp movements to saturate the market or withdraw a significant number of barrels from it to please someone else.

Treading cautiously along an icy road

The market is currently experiencing an unprecedented and intense struggle between the political and systemic (i.e., economic) factors that determine oil price dynamics. And the outcome of this struggle is still not clear. The political factors, like Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine, instability in Libya, and the hypothetical failure of negotiations on the Iranian nuclear program, push prices up. Whereas market fundamentals — economic factors — are behind the third consecutive week, since Aug. 30, of oil prices largely trending downward. Among these economic drivers, the most important are the reduction in Chinese demand under the influence of the ongoing pandemic and the expected slowdown in global economic growth caused by high oil and natural gas prices and value chain disruptions. In a normal situation, the influence of market fundamentals on the hydrocarbon trade is always stronger than that of political factors, and that economic influence is generally longer term in nature. However, the world is presently experiencing abnormal times. Political factors are not short lived anymore: The Kremlin’s aggression in Ukraine and the accompanying “oil weapon” games between Russia and the West will impact the price of crude for a long time, bringing acute unpredictability to the hydrocarbon market.

Moreover, recent reports published by the International Energy Agency (IEA) and OPEC have added fuel to the fire by offering significantly divergent conclusions. In its assessment, the IEA assumes that to meet global oil demand in the fourth quarter of the year, OPEC will need to produce 29.16 million bpd, which is well below the group’s August output of 29.35 million bpd. Meanwhile, OPEC itself assumes that in the fourth quarter of 2022 it will need to go 500,000 bpd above its August production level. By itself, such a significant discrepancy does not necessarily mean that one of these organizations has lost touch with reality. On the contrary, it suggests that the future is currently so unpredictable that multiple scenarios may be equally plausible. In such conditions, oil producers can move forward in only small steps, planning out their actions no more than a month in advance and avoiding taking drastic measures.

Meanwhile, siding with the West against Russia could itself have a tangible cost for Gulf producers. The sanctions war waged by the United States, the European Union, and their allies against Russia, no less than Putin’s invasion of Ukraine and the use of the Russian energy weapon against Europe, can push oil and gas prices up. Thus, the EU decision to impose a price cap on Russian oil already raises many questions among market experts. If Russia does not concede, then this decision is capable of potentially removing 2.4 million bpd of Russian oil from the market. Such volumes cannot be replaced instantly. In turn, the shortage of oil supplies will lead to an increase in prices, which will be further spurred by a likely increase in demand for tanker transportation as a result of Russia’s attempts to reorient its export flows. The EU and the U.S. apparently would like to have their cake and eat it too: create problems for Russia while also containing a possible oil price jump by increasing the production of Middle Eastern oil. However, the Gulf countries (along with others), which openly rejoice in the rain of petrodollars, do not quite understand why they should assume the cost of European efforts to put pressure on Russia in the form of lost potential profits. This approach is, of course, somewhat short-sighted: High oil prices almost inevitably carry the roots of a future decline and price crisis. But again, under the current circumstances, it is unrealistic to think about anything related to the oil market in time intervals of more than a year (or even a month), and adventures with short-term super-profits may well go unpunished.

The Russian bear stays

The market situation remains unpredictable, and it is not in the interests of key OPEC players to form an anti-Russian camp. Even with expected production losses, Moscow remains a major producer whose word can exert psychological pressure on the price environment. Moreover, given Russia’s production difficulties, it is always possible to write off the volumes of production increases that OPEC+ could not or did not want to provide: The Gulf monarchies can claim that although they would be happy to support the world with cheaper oil, Russia had again failed to fulfill its quota. In other words, Russia can still serve the interests of the cartel. Finally, OPEC participants do not quite understand why they should politicize the current reshuffle of economic forces in the global oil market. Due to the historical discount on its oil, Russia has, indeed, created a problem for Saudi Arabia, Iraq, and Iran in a number of Asian markets (primarily in India and China). However, in return, the oil producers of the Middle East have gradually moved or plan to move on the European market, where Russia has already become persona non grata. There is no need for political clashes; in most cases, each side’s balance of losses and gains remains essentially even.

Yes, we can?

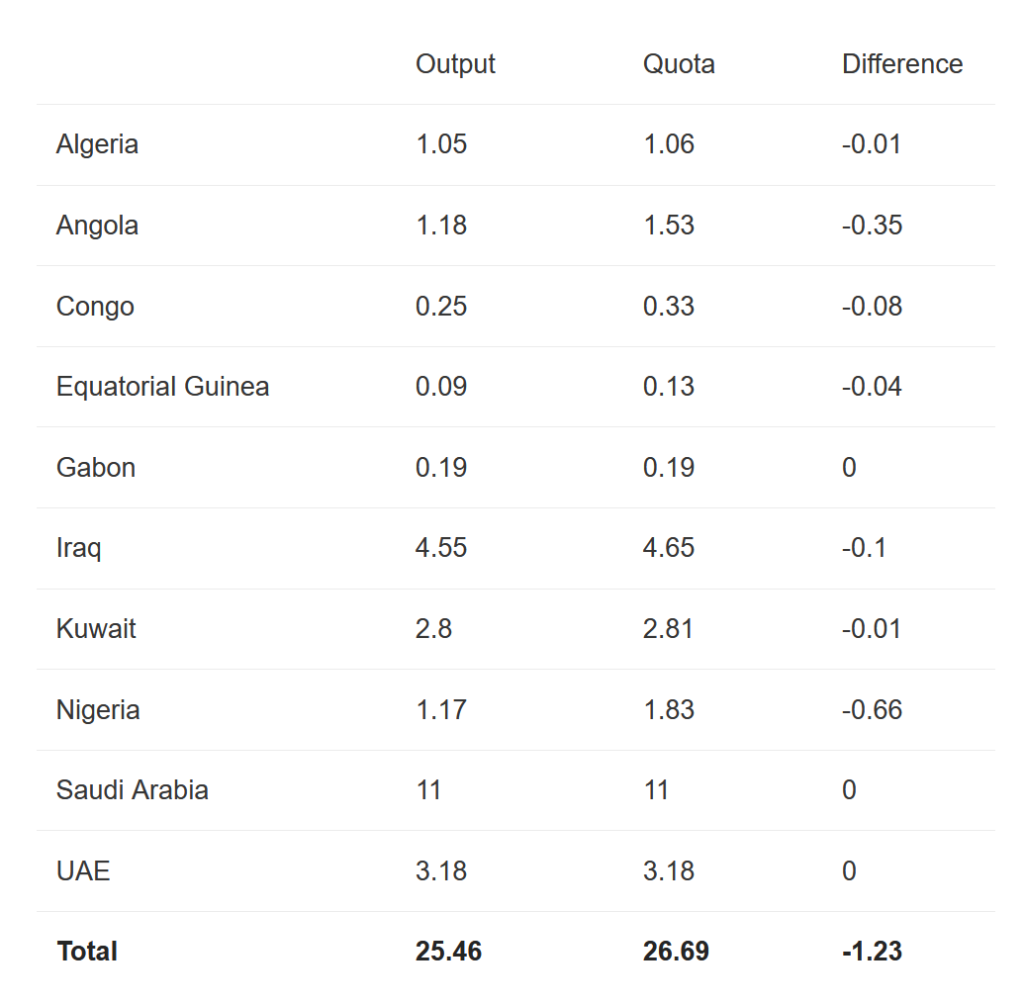

And finally, there is a technical factor that OPEC+ does not like to talk about. The big question remains whether OPEC can really leverage the situation in the market by using its own production capacities. On the one hand, how is it possible to talk about a sharp increase in OPEC’s production while the members of the cartel continue to fail to achieve their declared production volumes? Under-fulfillment of quotas occurs on a periodic basis. In some cases, even major players, such as Saudi Arabia, suffer from such deficiencies. By September, the production gap between the allocated quota and real output of the 10 OPEC members reached 1.23 million bpd — a volume that would have replaced a significant part of the Russian oil that has heretofore gone to Europe (see Table 1).

Table 1. OPEC Oil Output in August 2022 (million bpd)

For OPEC+ this figure stands even higher. According to Reuters, OPEC+ production is currently 3.58 million bpd below the total quota. On the other hand, despite the fact that the cartel has spare output capacity (estimated at 2.2 million-2.7 million bpd), no one has ever tried to check whether the cartel’s members (first of all, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) would be able to maintain this output for an extended period. Moreover, by tapping these reserves now, in the interests of the U.S. and the EU, OPEC countries would sacrifice their main instrument of international influence — spare production capacity. Meanwhile, the crisis is far from over, and these free barrels may still be needed. In the end, testing OPEC+ members’ true production capacities would reduce the effectiveness of the cartel’s psychological influence on the market by exposing what its participants can really do. Uncertainty remains in the interest of OPEC+: As long as the cartel can maintain the myth of its oil production primacy, even a slight increase or reduction of 100,000 bpd can have the desired effect when it comes to influencing the behavior of the market.

In a nutshell, the message that OPEC+ sent in August and September can be deciphered as the group’s unwillingness to follow anyone’s interests but its own, preserving the bloc’s key instruments of leverage for those times when OPEC members truly need them.