At the Paris Court of Justice, Ibrahim A. is trying to prove his innocence to the investigating judge questioning him.

“I come from Darfur,” he says. “We don’t even have a sea where you could learn to row a boat.”

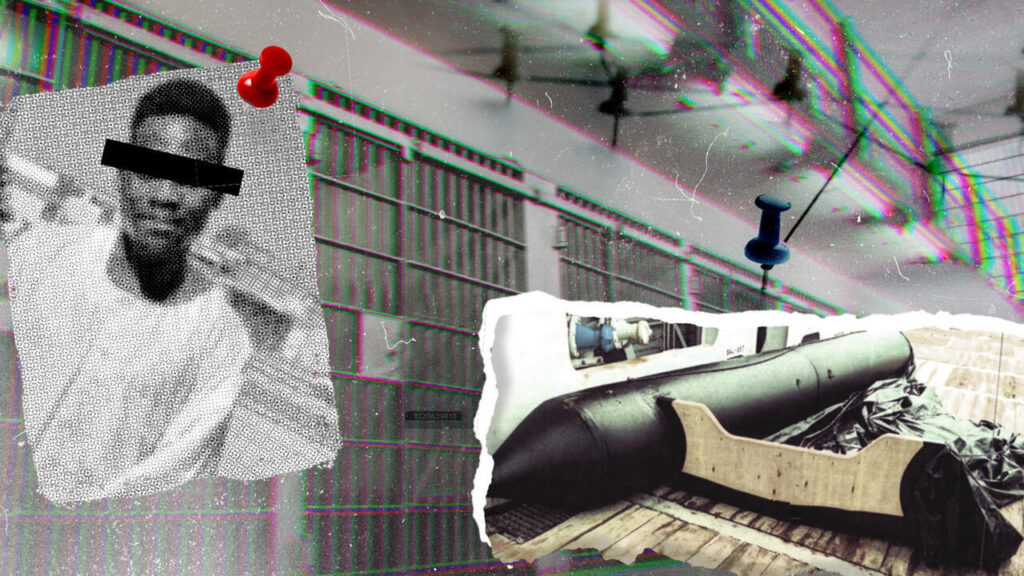

Ibrahim A. is originally from Sudan, the land-locked east African country that has been plunged into civil war since 2023. Four months before his appearance at the Paris court in December 2023, the 31-year-old was arrested and charged with involuntary homicide in connection with the sinking of a “small boat” that killed seven people in the English Channel.

He is now one of 10 suspects who will from November 4 be once again brought before a Paris court, accused of organising the deadly voyage.

Read moreOn the trail of migrant smugglers 1/3: The fall of Calais trafficker Idrees G.

Due to the complex nature of the case, it has been picked up by France’s national organised crime authority, la Juridiction nationale de lutte contre la criminalité organisée (Junalco).

Ibrahim A. is suspected of being one of two pilots of the seven-metre inflatable boat, which sank after an airpump exploded during its nighttime voyage across the Channel on on August 12, 2023. The boat’s 68 passengers, most of whom were Afghans, were plunged into the sea.

“I told myself, ‘it’s over, I’m dead.’” Ibrahim A. says of the moment the boat sank.

Out of 35 survivors questioned by French authorities, around 20 said Ibrahim A. and another passenger known as Tut E. had been piloting the boat.

In front of the investigating judge, Ibrahim A. denies the claim outright: “I was not the driver. In my opinion, these people didn’t want to implicate their brothers and preferred to implicate [myself and Tut E.] as the drivers.”

But the judge does not seem completely convinced. Not just because of the numerous testimonies incriminating Ibrahim A., but also because of what appears to be a deal struck with the smugglers who organised the voyage before he got on the boat.

Instead of the €1,000 that the other passengers paid to make the crossing, Ibrahim A. paid only €400, likely indicating he was assigned a specific task by the smugglers.

Ibrahim A. says the discount was a way for the smugglers to buying his silence and avoid word of the departure spreading among the Sudanese community. The cheaper price also meant that he was not given a life jacket, unlike some of the Afghan passengers.

‘Looking for a better life’

In his office in Paris, lawyer Raphaël Kempf says he did not hesitate to take on Ibrahim A.’s case.

Kempf is a prominent criminal lawyer in France who has worked on high-profile and highly politicised cases, including clients involved in the November 13 terrorist attacks and the Yellow Vest protest movement.

He says he is infuriated by the charges being brought against Ibrahim A.

Part of the judge’s questioning involved what the lawyer calls a “surreal” test of his client’s knowledge of the international standard ISO 12402, which regulates the manufacture of life jackets

“The judge’s objective was to demonstrate that there was negligence when it came to safety onboard that is characteristic of involuntary manslaughter. That’s why she brought up this standard,” he says.

“What the justice system is overlooking is that Ibrahim A. almost died that night.”

“I don’t think my client belongs in prison – he is not guilty of involuntary homicide, and the State has to take some responsibility,” he adds. “If we don’t know what he was running from, we cannot understand his absolute determination to get to England.”

Ibrahim A.’s explanation for why he stepped aboard the boat that night is simple.

“I got in to go and look for a better life,” he says.

The Sudanese migrant has travelled 4,500 kilometres from his homeland, which has been gripped by violence since 2003 and is currently in the throes of a violent civil war. In Darfur, the Arab Janjaweed militia group are persecuting non-Arab groups such as the Masalits, to which Ibrahim A. belongs.

Read moreUN accuses Sudanese forces of crimes against humanity amid Darfur crisis

One day, while he and his brother were taking their herd out to graze, they were threatened by armed Janjaweed. Their family was forced to flee to escape the violence, first to a camp for displaced persons in Darfur’s Krinding, then across the border to a camp in Adre, Chad, which is currently home to 280,000 Sudanese refugees.

In spring 2023, as his mother fell ill and the humanitarian situation around them began to deteriorate, Ibrahim A. decided to leave.

His wife, Ikbal, has already been granted asylum in the US where she was working as a nurse, but Ibrahim A. set his sights on western Europe.

Without a specific destination in mind, he travelled to Libya by car and then crossed the Mediterranean by boat, landing in Italy before he reached France.

“When I arrived in France I wanted to have my fingerprints taken but I had difficulties with the language,” he says. “I understand English much better, and that’s why I wanted to go to England.”

Our series: On the trail of migrant smugglers

Taking responsibility

The English Channel is a dangerous for small boats – 78 migrants died in its waters in 2024 – and France is cracking down on smugglers who organise crossings.

In courts in northern France, where small boat pilots appear regularly, “the sentences handed down range from six months for someone driving a boat for the first time to one or two years in prison for someone who has done multiple journeys and must, therefore, be part of a network”, says Pascal Marconville, first advocate general at the Court of Appeal of in the northern town of Douai.

Even though Ibrahim A. insists that he has nothing to do with the alleged traffickers who will appear alongside him in court in November, the fact that the national investigators from Junalco have picked up the case suggests a heavy sentence is likely.

“Everyone has their own responsibilities and level of involvement, but he knew he was piloting a boat that was in poor condition and that the crossing was dangerous,” a source close to the investigation told FRANCE 24.

Held in pretrial detention for more than two years in a prison near Paris, Ibrahim A. has had time to reflect on the shipwreck, learn French, and file an asylum application – which was denied.

The French authorities that studied his case said his application had “insufficient” evidence “to establish with certainty” that he comes from West Darfur.

Kempf filed an appeal with France’s national asylum courts but suspects the real reason Ibrahim A. was refused is quite different.

“I think the authorities denied him asylum because he is in prison,” the lawyer says.

The ordeal is taking its toll on the Sudanese migrant. At a preliminary court hearing in October, as Kempf gave his closing arguments, Ibrahim A. broke down in tears.