Abstract: On January 18, 2023, the military regime in Burkina Faso demanded that France withdraw its troops from the country within a month, stoking fears that another African country is set to hire the Kremlin’s favorite mercenaries, the Wagner Group, to help contain Burkina Faso’s worsening jihadi insurgency. There seems to be a very significant probability that the military government in Burkina Faso will indeed hire Wagner in the near future. The leader of Burkina’s junta, Captain Ibrahim Traore, currently faces intense pressure from both within his country and neighboring Mali to bring in Wagner mercenaries to stabilize the security situation. Though it is important to stress that Burkina Faso has already turned to private military companies, any move to hire Wagner Group would be a symptom of the malaise caused by weak and hollowed-out state institutions, corruption, and the increased militarization of Burkinabe society. Nevertheless, a future potential Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso would likely result in a further upsurge in jihadi violence in Burkina Faso given the fact that jihadi attacks, perpetrated by both JNIM and the Islamic State, have increased dramatically across Mali since Wagner’s deployment there just over a year ago. And a Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso would further entrench Russian influence in Africa, complicate Western policy in West Africa, and create humanitarian concerns given Wagner’s reprehensible human rights record.

On January 18, 2023, Burkina Faso’s military regime officially announced that it was ending its military accord with France that had been in place since 2018.1 In addition, the ruling junta in Ouagadougou, led by Captain Ibrahim Traore, requested that French troops, stationed in the country as part of France’s Operation Sabre, leave Burkina Faso within a month.2 The removal of French troops comes after several months of intense anti-French sentiment from the junta, who also requested the withdrawal of France’s ambassador in December 2022.3 Burkina Faso has now joined its northern neighbor of Mali in officially ending military ties with France after more than a decade of French-led counterterrorism missions throughout the Sahel. With Russia’s favorite private military company, the Wagner Group, already deployed in Mali for over a year, there is intense speculation that Ouagadougou may also hire the Russian mercenaries.4

Led by Traore, the ruling junta in Ouagadougou came to power in September 2022 in Burkina Faso’s second coup d’état in less than nine months by overthrowing Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, the military officer who led the country’s previous coup in January 2022.5 Much as Damiba had done to his predecessor in the earlier coup d’état, Traore and his allies publicly argued that Damiba had done little to stymie the continuously mounting jihadi insurgency inside the country.6

This so-called ‘coup within a coup’ in Burkina Faso comes during a period of geopolitical transition in the Sahel. France, the former colonial power and the region’s longtime security behemoth since 2013, withdrew from Mali with its final troops leaving the country in August 2022.7 In its place, Mali has brought in Russia’s aforementioned favorite plausible deniability asset, the secretive Wagner Group.8 With the popular protests related to Burkina Faso’s most recent coup featuring some overt pro-Russia sentiments, pundits, analysts, policymakers, and other relevant stakeholders within the international community have rightfully questioned if Burkina Faso will be Wagner’s next destination.9 In early October 2022, the United States warned Burkina Faso not to ally with Russia (and by extension, Wagner). President Traore assured U.S. diplomats that he had no intention of inviting Wagner troops to fight militants in the country, U.S. Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs Victoria Nuland told the media in late October. The Russian war-media Telegram channel Rybar claimed in a December 18, 2022, post that the U.S. warning had come too late, claiming that “the Wagnerites are already conducting reconnaissance, and negotiations are in the final stage.”10 a Concerns that Wagner may deploy to Burkina Faso have grown in recent weeks,11 with reporting suggesting that Wagner has already started to deploy to Burkina Faso—though the junta itself has not confirmed any Wagner presence in the country.12

In light of these fears, this article serves as an exploration of a possible Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso and what the implications might be. The article also assesses Wagner’s previous fortunes (or oftentimes misadventures) in Africa. Wagner remains a popular alternative to Western powers among several African states and leaders, though its operations inside Africa have often been more detrimental than beneficial. It is important to note that Burkina Faso has already relied on private military companies (PMCs) in its fight against jihadis. And that if the country hires Wagner, it would only be a symptom of the wider structural malaise plaguing Burkina Faso. As this article will outline, the country’s deep-seated problems are due to corruption, the hollowing-out of state institutions, and a militarization of society caused by the mobilization of civilian militias.

Starting with a brief background of Burkina Faso’s political instability during the last decade, this article then turns to providing an overview of the country’s worsening jihadi insurgency and the concerning spillover of jihadi violence into littoral states. The article then examines the likelihood and repercussions of a potential Wagner Group deployment inside Burkina Faso.

Part One: A Decade of Political Instability in Burkina Faso

The September 2022 coup d’état in Burkina Faso is in many ways emblematic of the country’s tumultuous political climate since 2014. Though the country has a long history of coups, revolts, and foreign meddling,13 all of which have undoubtedly contributed to Burkina’s current political instability, this article will focus on its political history over the last decade, including the most recent government overthrow. What is most important to understand are the motivations of the key protagonists within Burkina Faso. The policies and personal desires of these individuals have not wholly created the current concerning state of affairs in Burkina Faso but will help determine whether and to what extent Russian mercenaries will be hired by the country.

The late September 2022 coup saw Traore, a previously unknown captain within Burkina’s army who led an artillery regiment in the country’s north, overthrow the previous junta leader, Lieutenant Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba.14 Traore, himself a member of the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration (MPSR)—the movement led by Damiba that perpetrated the January 2022 coup—appointed himself the new leader of the MPSR in a televised address shortly after deposing Damiba.15 A few days later, the MPSR formalized this appointment by announcing Traore as the new interim president of Burkina Faso.16 After mediation by local community leaders, Damiba was allowed to go into exile and fled to neighboring Togo.17 Since coming to power, Traore has attempted to assuage concerns from the international community by saying he still intends to allow planned elections by July 2024 “if the situation allows it.”18 b

Traore’s Motivations

Damiba’s failure to improve the steadily deteriorating security situation has frequently been cited as the primary driver of Traore’s coup. Indeed, a deadly ambush in late September 2022 by al-Qa`ida’s West African branch, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM), against a transport convoy escorted by soldiers and Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland (VDP)c near the village of Gaskinde was apparently the final straw for those seeking to overthrow him. At least 27 soldiers and 10 civilians were killed, dozens were wounded, and others went missing, according to a government statement.19 Indicative of the Burkinabe military’s monumental failure to secure the convoy heading to resupply the town of Djibo, the provincial capital of the northern Soum Province, is that JNIM claimed at least 90 trucks and military vehicles were burned in the attack.d Subsequent analysis of satellite imagery by the investigative journalism group Bellingcat confirmed that 95 vehicles had been destroyed in the attack, scattered along a more than five-kilometer strip of road.20 e

However, the worsening jihadi violence was far from the only factor that precipitated the most recent coup. Other factors played an equally important role. One was unpaid bonuses estimated at six million CFA (approximately 10,000 USD) per soldier. Another was Damiba’s special treatment of the army’s special forces through the allocation of land parcels that sowed further discord within the ranks of the armed forces.21

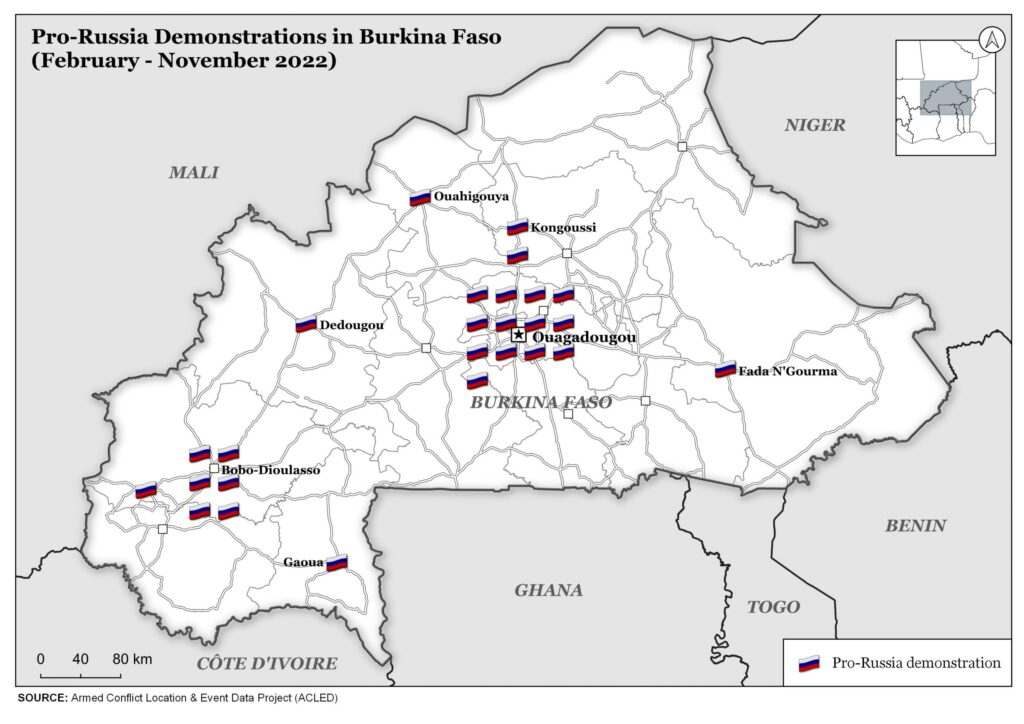

Popular protests occurring throughout Burkina’s capital of Ouagadougou related to the September 2022 coup revealed explicit pro-Russia sympathies that portended a widening battle between France and Russia for influence in the country and the region. For instance, on October 1, 2022, protestors were widely seen waving Russian flags,22 particularly at the French embassy in Ouagadougou, after rumors that Damiba was sheltering there ran rampant amid the chaos.23 In Bobo-Dioulasso, a city in Burkina’s southwest, a French cultural center was also targeted by protestors.24 Pro-Russia demonstrations occurred off and on throughout 2022, with nearly 30 such demonstrations recorded in various urban centers (see Figure 1), although the vast majority were concentrated in Ouagadougou and the second largest city, Bobo-Dioulasso.f

It is difficult to unravel to what extent Russian actors are whipping up such sentiment. In January 2023, an influence operation targeted the population of Burkina Faso through an animated video clip depicting the Wagner Group as a good friend and savior of Burkina Faso and Mali, and France as an evil enemy in the form of demons and a giant cobra snake.25 The clip was infantile and unsophisticated, but it cleverly reinforced anti-France narratives.

On January 20, 2023, several hundred people gathered in Ouagadougou to again protest the French military presence in the country with Russian President Vladimir Putin and Traore featured on large adjoining banners.26 As already noted, two days earlier, the junta had withdrawn from the military accord with France and demanded that French troops leave within a month.

Notwithstanding the optics of such demonstrations, Traore himself has played coy on his sentiments regarding Russia, saying that Burkina Faso has “many partners.”27 France strongly denied rumors it was interfering on the ground on the side of Damiba during the September 2022 coup.28 And although the Russian state has not formally commented on the coup, Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin, founder of the Wagner Group and a close ally of Putin, stated he “salute[s] and support[s] Captain Ibrahim Traore” who he calls “a truly courageous son of the motherland.”29 Prigozhin’s statement was likely meant to publicly open the door for cooperation between Wagner and Burkina’s new junta, in addition to acting as a means to further divide public sentiment between the Burkinabes and France, though any hard confirmation of further Wagner interference in Burkina apart from rhetorical support to the new junta has not come to light as of late January 2023. That said, since the beginning of 2023, there have been a number of reports from independent news outlets suggesting that a deal between Burkina’s junta and Wagner is closer than ever—though the Burkinabe junta itself has not confirmed these rumors.30

Damiba’s Downfall

Damiba himself came to power earlier in 2022 after he was appointed interim president of Burkina Faso by the MPSR after leading the overthrow of President Roch Marc Christian Kabore in January 2022.31 Somewhat ironically, Damiba and his allies in the MPSR had accused Kabore of doing little to stop the jihadi insurgency throughout the country—the same public accusation Traore levied at Damiba during his coup in September.32 Damiba and the MPSR promised to improve the security situation and assured Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) that there would be a return to civilian rule in the aforementioned 2024 elections.33

However sincere Damiba and the MPSR might have been in making these promises, his brief rule in Burkina Faso was marked by continued insecurity,34 a series of massacres perpetrated by jihadis,35 and a worsening spillover of jihadi violence out of Burkina Faso and into a number of littoral West African states.36 Damiba apparently aimed to find a way out of the conflict by devising a more comprehensive strategy. He was convinced that Burkina Faso’s problems were not only military but also political, which resulted in him incorporating or giving greater weight to political components such as amnesty, demobilization, and reconciliation, which had been largely absent until then.37 By establishing local committees, he sought a platform for dialogue, negotiation, and demobilization of Burkinabe combatants who had taken up arms against the state. Some 250 combatants laid down their arms under the program, which also provided funding for development projects, vocational training centers, and reinsertion projects in the domains of breeding livestock, agriculture, and transport.38

Despite Damiba actively seeking political solutions to the crisis in Burkina Faso, he by no means abandoned the military path. This was evidenced by the fact that he personally oversaw Burkina Faso’s secretive drone program after the country acquired Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones that were operational by February 2022 (or perhaps even earlier.)39 Numerous military operations were conducted during Damiba’s rule, including the staggering number of more than 200 airstrikes and repelled attacks that in total killed 1,291 militants, according to data collected by the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).40 This closely corresponds to an unofficial toll provided by an anonymous Burkinabe military source, who listed the results as 1,300 militants killed, more than 20 bases destroyed,41 and the approximately 250 demobilized combatants mentioned earlier.

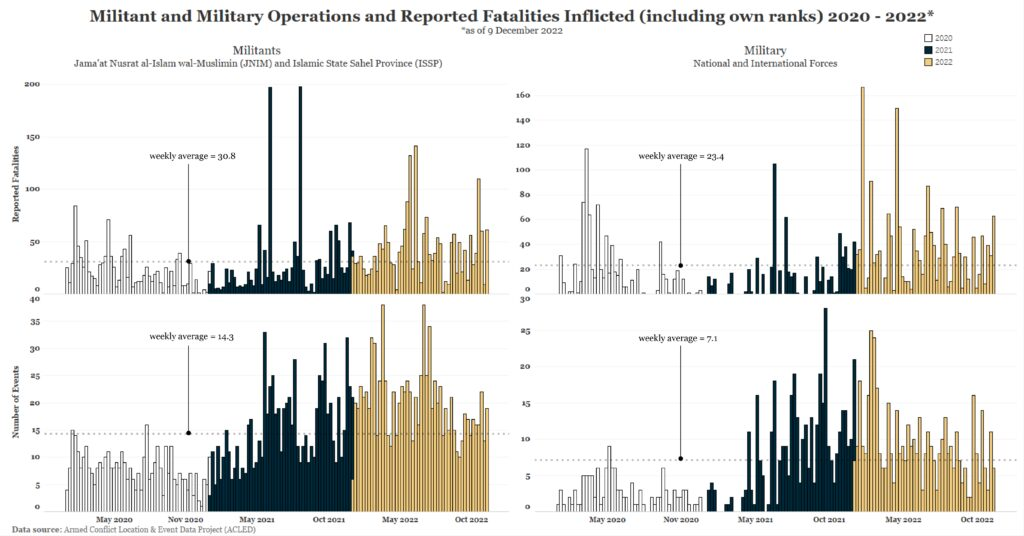

Regardless of Damiba’s efforts at the military and political level, the problems Ouagadougou faced were clearly profound and the crisis deep-rooted. Damiba was overly publicly optimistic in his statements about what he could achieve in the short term,42 raising public expectations while the situation continued to deteriorate during his tenure. What is clear, however, is that Burkinabe military efforts during Damiba’s government were overwhelmed and outpaced by the steadily increasing operational tempo of the militant groups, as measured by the violent events they (and particularly JNIM) initiated and the resulting fatalities (Figure 2).g

Apart from being overly optimistic that he would be able to deliver on his promises to improve the security situation and recapture lost territories, Damiba probably also felt too comfortable in his position. This was made clear in a speech before stakeholders during a visit to Bobo-Dioulasso in May 2022, when he called on anyone who was dissatisfied with his rule to attempt a coup against him.43 Moreover, Damiba was also open to continued military cooperation with France.44 That Damiba favored maintaining and deepening military cooperation between the Burkinabe military and the French troops of Operation Barkhane,45 played into the hands of his opponents and detractors, who took advantage of the growing anti-French sentiment in the country. Burkina Faso was one of France’s favored counterterrorism partners alongside Niger, as France reshaped its regional counterterrorism mission Operation Barkhane (now officially ended) after its withdrawal from Mali.46 Thus, it was no surprise that on the streets of Burkina Faso, pro-Russia voices became loudest and most visible. In fact, calls for military cooperation with Russia had immediately followed Damiba’s own coup d’état in January 2022, to which he did not respond with any tangible overtures. To the contrary, he refused to contract Wagner, despite the efforts of the junta in neighboring Mali to facilitate this during a meeting he undertook with his Malian counterpart, Assimi Goita.h

Traore’s Approach

Unlike his predecessor, the current transition president, Ibrahim Traore (who is commonly referred to by his initials IB), has adopted a populist approach and chosen the path of “total war.”47 A key aspect of Traore’s approach is an accelerated mobilization of the population for the VDP program following incessant calls for the arming of civilians. After Traore’s transitional government called for the recruitment of 50,000 volunteer fighters, 90,000 people reportedly responded.48 The mass mobilization clearly shows that Traore has assigned the VDP a key role in his military strategy to take back lost territories.i His involvement with the VDP predates the coup, as he was previously the chief of Kaya’s artillery regiment, responsible for training the VDP in places such as Noaka, Bouroum, and Pensa in the Centre-Nord Region where his regiment is based. The VDP around Traore were expected to play the role of force multipliers on the day of the coup in case the events would take a different turn and degenerate into clashes between Damiba loyalists and those on Traore’s side.49

Critics of the VDP program point out that the state-backed self-defense militias have been recruited predominantly from settled communities since their official establishment in January 2020 under former President Roch Kabore.50 j Since their establishment, the self-defense militias have contributed to an increase in violence and an increase in recruitment from pastoralist communities by jihadi groups.51 There are fears that abuses, summary executions, and attacks could increase amid the ongoing mass mobilization, leading to even more violence and triggering a larger intercommunal crisis with ethnic dimensions.k

Part Two: The Growing Jihadi Insurgency in Burkina Faso and the Spillover into Neighboring Littoral States

The Jihadi Insurgency in Burkina Faso

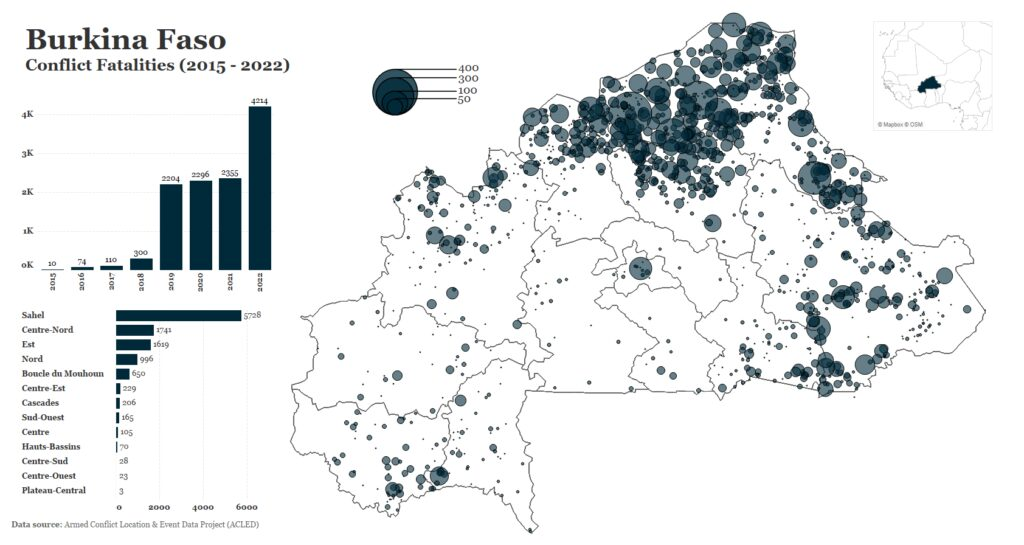

Burkina’s jihadi insurgency both started and vastly expanded during the rule of Roch Marc Christian Kabore. When he came to power in 2015 after Burkina’s first elections, which followed nearly 30 years of rule by longtime authoritarian leader Blaise Compaoré, Kabore’s rule was marked by the rise of jihadi violence in the country. After the insurgency began in earnest in late 2016, it was initially confined to a remote corner of the northern province of Soum, the birthplace of the Burkina Faso domestic jihadi group Ansaroul Islam.52 Since then, however, the insurgency has spread to 11 of the country’s 13 regions.l By the end of 2022, conflict fatalities had increased by 77 percent compared to 2021, making 2022 the deadliest year since the conflict began in Burkina Faso in 2015. (See Figure 3.)

Burkina Faso has been the subject of simultaneous campaigns by JNIM and its Islamic State rival, the Greater Sahara branch of the Islamic State’s West Africa Province (ISWAP-GS, or more colloquially known as Islamic State Greater Sahara, or ISGS). This group was elevated to the status of its own province—the Sahel Province of the Islamic State (or ISSP)—in March 2022.53 For years, the territory of Burkina Faso was the scene of growing competition between the regional branches of al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State, eventually escalating into a full-blown turf war largely concentrated in the far north of the country.54 ISSP is largely confined to the northeastern provinces of Oudalan and Seno, and continues to wreak havoc there, having gained dominance in the Liptako-Gourma region, commonly known as the tri-state border area.55 However, it is important to note that ISSP has not been able to sustain its expansion, as JNIM controls or exerts influence over large portions of Burkinabe territory and continues to spread throughout most of the country with its activities increasingly approaching the capital, Ouagadougou.56

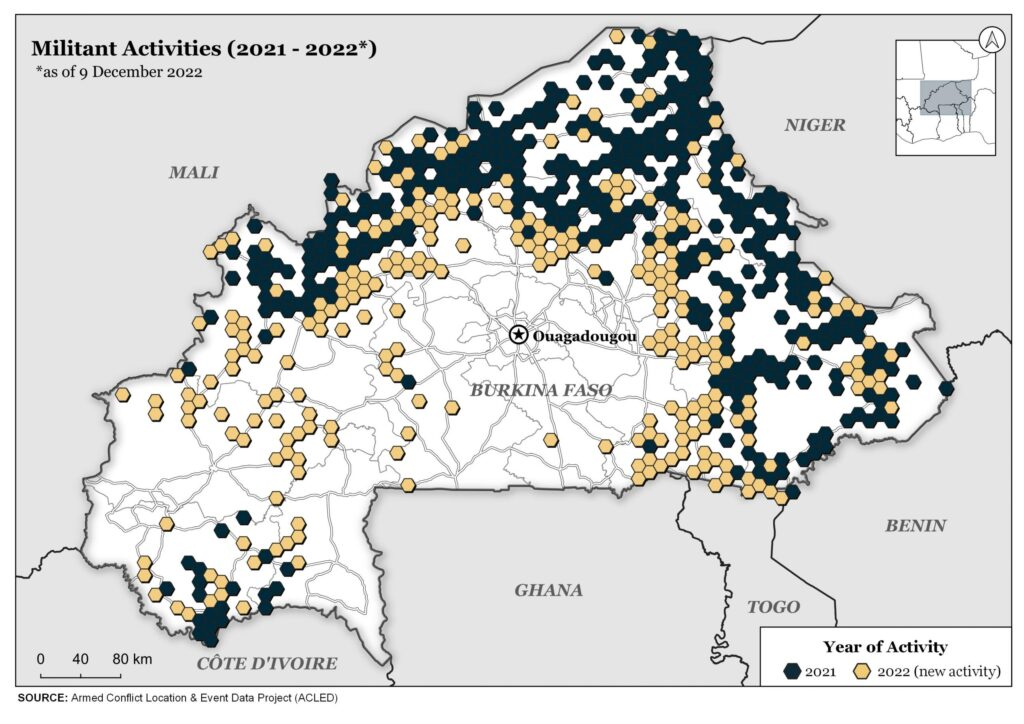

During Damiba’s period in power, JNIM continued to expand into new areas in several regions and increased its activities in others that had previously served as support zones rather than areas for military operations by its fighters.m Taken together, this led to increased encirclement of Ouagadougou within a radius of about 90-110 kilometers in all directions around the capital (see Figure 4, with new activity recorded in 2022 displayed in yellow). This trend has continued since Traore came to power. Today, the situation remains critical in many parts of the country due to the humanitarian emergency accompanying the security crisis and the fact that many towns and villages are under suffocating militant blockades.n

Emblematic of the continued deterioration of security under Traore, JNIM overran a regiment-sized base in the northern town of Djibo in October 2022, killing at least 10 soldiers.57 This was followed by its two-day attack in early December 2022 against an Essakane Mine logistics convoy in Burkina’s Centre-Nord Region, burning at least 60 vehicles and leaving many drivers missing.58 This attack had similarities to JNIM’s aforementioned September 2022 ambush near the northern village of Gaskinde that killed 27 soldiers and 10 civilians and helped trigger the September coup against Damiba.59

The Jihadi Spillover into the Littoral States

With JNIM making a concerted effort to consolidate its power and influence inside Burkina Faso, its violence has not been confined within its borders. JNIM has used its positions, particularly inside the southeastern Burkinabe province of Kompienga (which it effectively controls),60 to strike inside both Benin and Togo on numerous occasions, with these cross-border attacks picking up pace in 2022.61 This is not dissimilar to the situation in Burkina’s southwestern provinces of Comoe and Poni, from where JNIM had earlier managed to infiltrate northeastern Côte d’Ivoire.62 The violence that encapsulates much of Burkina Faso is being exported to its southern neighbors.

Though al-Qa`ida had previously struck inside littoral West Africa prior to the deterioration of Burkina Faso’s security, particularly with the March 2016 attack in Grand-Bassam, Côte d’Ivoire,63 it was not until June 2020 that operations by the group into the littoral states from bases and staging points inside Burkina Faso began in earnest. That month, 14 Ivorian troops were killed by militants from JNIM’s Katibat Macina in northeastern Côte d’Ivoire.64 o And though attacks in Côte d’Ivoire have since declined, jihadis, primarily JNIM, have since regularly attacked other littoral states from their bases in Burkina Faso at a rapidly increasing tempo.65

Although Benin witnessed a handful of jihadi incidents between May 2019 and March 2021, it was not until late 2021 that violence seeping out of Burkina—largely from JNIM—constituted a more constant threat. Since December 2021, Benin has recorded at least 17 incidents related to jihadi violence.66 Though JNIM is believed to have perpetrated or have been involved in the vast majority of incidents, the Islamic State’s regional franchise has also publicly claimed at least two operations inside northern Benin.67 Togo was largely spared jihadi violence until its military repelled a suspected JNIM incursion into its territory in November 2021. Since then, the small West African state has been targeted at least an additional 11 times.68

Taken into context, it is clear that the jihadi violence expanding across Burkina Faso does not just affect that country. It also threatens the stability of Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, Benin, and to a lesser extent Ghana. All four countries have had to reinforce their northern borders, enact new security policies or operations, and in the case of Benin, reach out to Rwanda for better security guarantees.69 There is great pressure, therefore, on Burkina Faso—and international actors—to finally contain the insurgency within its borders. For some time, there has been concern that Burkina Faso may respond by turning to the Russian Wagner Group.

Part Three: The Likelihood of a Wagner Deployment and its Repercussions>

Internal and External Pressure to Hire Wagner

Traore currently faces both internal and external pressure to work with Wagner. The Burkinabe ‘street,’ from which he received support during and after the coup, has been demonstrating repeatedly for nearly a year, demanding military cooperation with Russia and French withdrawal.p Another factor is that several officers within the new MPSR (or MPSR 2, which the junta under Traore is referred to as) are calling for a partnership with Wagner, or another private military company, citing military fatigue.70 Several mining and construction companies have also called for PMCs to be brought in to protect them, although these requests have so far been rejected.71 Adding to their sense of insecurity, on four occasions between June and October 2022, JNIM fighters attacked security positions and employees at the Karma mine in Namissiguima in the Nord region.72 JNIM fighters also attacked a logistics convoy of the Essakane mine twice on the Kaya-Dori road between December 8 and 9, 2022, with the devastating result of nearly 30 fuel tankers and trucks burned.73 However, if the security situation does not improve, it is likely that businesses and economic operators will increase pressure on the government to hire PMCs to protect their interests and ensure the security of their activities. It is possible that some may issue an ultimatum by threatening to move their operations out of the country if their security needs are not met.

Hardening Anti-French Sentiment

In early December 2022, Burkinabe authorities suspended the broadcasting of Radio France Internationale (RFI) in the country for reporting on a video message released by Ansaroul Islam.74 RFI was not the only media outlet to report on the issue, however. The video message was widely circulated, and local mainstream media also reported on the matter without any apparent reprisals. This may suggest that the decision was merely a pretext for a more hostile attitude toward international and particularly French media operating on Burkinabe territory, which strongly resembles the approach adopted by neighboring Mali, albeit in a softer manner than by the Bamako junta.75 q

The suspension is indicative of an increasingly hostile environment toward France in Burkina Faso. There have been repeated demonstrations and vandalism against French facilities, including the French embassy, the French Institute, and the military base in Kamboinsin where French forces have been based.76 Military relations between the two countries also soured after Burkinabe authorities in early October 2022 suspended French military flights in the country “until further notice.”77 Though the suspension was brief and lasted a few weeks, the government in Ouagadougou made the resumption of flights contingent on the mandatory presence of Burkinabe commandos on certain flights. Creating further tensions, on the night of December 17-18, 2022, the Defense and Security Forces (FDS) arrested and expelled two French nationals accused of espionage because of their interest in military activities, according to the state-owned Agence d’Information du Burkina (AIB), citing security sources.78 Again, the event was reminiscent of the arrest and brief detention of two French soldiers in mid-September 2022 in Bamako, Mali.79

On December 23, 2022, authorities in Ouagadougou declared the resident humanitarian coordinator of the United Nations, Barbara Manzi, persona non grata and ordered her to leave the country on the same day.80 That same month, the junta in Ouagadougou also requested the French ambassador, Luc Hallade, to leave Burkina Faso, though France stood by its diplomat, refusing to withdraw him,81 but ultimately recalled the ambassador “for consultations” on January 26, 2023.82 This increasingly hostile attitude toward the French and the international community comes in the wake of a rapprochement between Ouagadougou and Bamako, as the heads of the junta of the two countries met in the latter’s capital in November.83 In the wake of Ouagadougou ending military cooperation with Paris on January 18, 2023, it is all too easy to imagine that talks on defense and security issues between the countries included discussions (as previously between Damiba and Goita) of Burkina Faso allying itself with Bamako’s new preferred military partner, the Wagner Group.

Strengthening Ties with Russia

On September 25, 2022, just a week before Damiba’s ouster, the then-Burkinabe leader met with Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov on the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly, ostensibly to strengthen bilateral relations between Burkina Faso and Russia.84 Following the abrupt end of Damiba’s rule, relations between the two countries have only strengthened. Immediately after the coup, Russian Ilyushin Il-76 transport aircraft delivered weapons and helicopters previously ordered by Damiba to Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso. As reported by Africa Report, “these orders for arms and helicopters were placed by the old authorities, Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, and validated by the new ones, Captain Ibrahim Traore and his men, once the coup had taken place.”85 Shortly thereafter, in late October, the newly appointed Burkinabe prime minister, Appolinaire Kyelem de Tembela, publicly stated that Burkina Faso would reconsider its relationship with Russia.86 In early December, Kyelem carried out a discreet blitz visit to Moscow facilitated by Mali, which sent a plane to pick up the Burkinabe prime minister in Ouagadougou, from where he traveled to Russia via Bamako and Istanbul.87 Jeune Afrique, which broke the story of the prime minister’s Moscow trip, quoted an unnamed regional source as saying that Kyelem sought to acquire military equipment and that French officials believed the visit could facilitate the meeting with Wagner Group executives.88

The History of PMCs in Burkina Faso

When considering the possibility of the Wagner Group deploying to Burkina Faso, it is helpful to consider the historical context of PMCs and private security companies (PSCs) operating in the country. Burkina Faso has already relied on PMCs to help in its fight against the jihadi insurgency ravaging its border areas. As such, if Wagner is hired by the junta, it would only be symptomatic of a growing hollowing and weakening of the country’s political, security, and military institutions.

The hiring of PSCs to protect businesses and sensitive assets and facilities, particularly in the mining sector, has not been uncommon in Burkina Faso.89 Their presence in the country was highlighted when militants from al-Murabitoonr abducted Romanian security guard Iulian Ghergut from the Tambao manganese mine in Burkina Faso’s northern Oudalan province in April 2015.90 Ghergut is the longest-held Western hostage in the Sahel and remains in captivity to this day. Compared to PSC activities, less is known about PMC activities in Burkina Faso, although the Ukrainian PMC Omega Consulting openly featured its operations in Burkina Faso on its Facebook page in 201891 and ran a training facility there.92

Ukrainian and Bulgarian mercenary pilots (referred to as “contractors”) were deployed to Burkina Faso in December 2018,93 coinciding with the delivery of helicopters from Russia and Bulgaria in late 2018 and early 2019.94 While it is normal for mechanics and trainers to be part of the package in the transfer of military hardware such as aircraft and helicopters, in this case, the Ukrainian and Bulgarian pilots conducted combat missions, including an airstrike January 30, 2019, on the ‘wrong’ village.s The pilots attacked the village of Zourma, some 130 kilometers from the intended target in Kompienbiga,95 where JNIM fighters earlier the same day had overrun an army camp.96

The pilots were reported to have either been contracted by the company Aranko Security or an unnamed Ukrainian PMC.97 Considering the timing of the aforementioned activities by Omega Consulting, it is possible that it is the unnamed PMC in question. Regardless, the helicopter sale and the contracted mercenary pilots were all reportedly interconnected through a scheme of front companies linked to murky arms deals overseen by then-President Roch Kabore.98 The Aranko Security and Ralph companies, run by a French-Lebanese businessman of Armenian origin, Rafi Dermardirossian, reportedly had close contacts with Kabore and brokered the transfer of a refurbished Mi-24 attack helicopter from the Bulgarian defense firm Metalika to the Burkinabe state, in addition to a series of arms deals since 2016.99

Wagner’s Track Record in Africa

Wagner’s activity on the African continent is well-documented. Wagner’s first major deployment to Africa was to Sudan in 2017, helping the then-government of Omar al-Bashir put down protests in exchange for Russian access to Sudanese gold mines.100 Then in 2018, Wagner deployed to the Central African Republic (CAR) following a similar deal signed by CAR’s government to receive Russian military support in its civil war in exchange for Russian access to CAR’s lucrative mining sector.101 Though not initially involved in combat operations, by late 2020 as the security situation in CAR deteriorated, Wagner became one of the most significant armed actors in the conflict according to ACLED data.102 The majority of Wagner’s military activity in CAR was directed against civilians.103

In 2019, Wagner expanded its operations in Africa with high-profile deployments to both Libya and Mozambique. In Libya, the Russian private military company assisted General Khalifa Haftar retake vast swaths of territory across the country’s north and mount an assault on Tripoli, the seat of Libya’s internationally recognized government.104 During its deployment to Mozambique, Wagner assisted the central government in Maputo in its fight against the Islamic State’s insurgency in the country’s northern province of Cabo Delgado.105 Though Wagner is still believed to be active inside Libya, it quietly withdrew its men from Mozambique just three months after its initial deployment following the loss of 10 men in combat operations.106

Most recently, Wagner expanded its presence in Africa by deploying to Mali.107 Following Mali’s own series of recent coups, the Wagner Group was invited to deploy by the country’s new strongman, Assimi Goita, after France fell out of favor with the ruling junta.108 As France was withdrawing its troops, Wagner entered Mali in late 2021. Since the beginning of 2022, the addition of Wagner has only compounded violence toward civilians, with the militia itself behind several massacres, such as a mass killing in central Mali in March 2022 that left at least 300 civilians dead.109 To further highlight the impact of Wagner, civilian deaths were higher in the first quarter of 2022 than all of 2021 combined.110 In all, Wagner’s deployment in Mali has served to further worsen the jihadi threat in not only Mali but the wider Sahel region.111 Jihadi attacks, perpetrated by both JNIM and the Islamic State, have dramatically surged across Mali since Wagner’s deployment.112

The Potential Repercussions of a Wagner Deployment

Judging by its impact in Mali, a future potential Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso would likely exacerbate the climate of fear, and their presence would be detrimental to civilian security in areas where the PMC would operate alongside local government forces. Wagner mercenaries could also alter the fragile power equilibriums between armed groups that are largely mobilized along ethnic lines, negatively impacting conflict dynamics and leading to settlements of accounts and retaliatory attacks with a high risk of mass atrocities. In addition, the information environment will undoubtedly be heavily influenced by disinformation, and lethal tactics not previously employed by local government forces and their allies could potentially be introduced, as has already been seen in other countries where Wagner mercenaries are deployed, including CAR, Libya, and Mali.113 Combined, this will likely result in an upsurge in the jihadi threat in Burkina Faso just like in Mali. As Wassim Nasr recently noted in this publication:

The arrival of Russian mercenaries [in Mali] hastened the departure of French and European forces. However, the Russian private military company did not deploy capable, disciplined, and well-equipped troops to fill the gap, and its brutal and indiscriminate counterinsurgency efforts are serving as a recruiting tool for the jihadis. A year after the arrival of the Russian mercenaries to Mali, the security situation has worsened. Despite ongoing fighting between al-Qa`ida and the Islamic State’s branches in the Sahel, the two terrorist groups are consolidating their sanctuaries and gaining an unprecedented range of action.114

A Wagner deployment would undoubtedly also lead to increased tensions between Burkina Faso and the West, especially France, leading to a decrease or a full cessation of Western assistance. The possibility of a Wagner deployment also threatens regional initiatives to counter the jihadi violence. For instance, in December 2022, Ghana’s president, Nana Akufo-Addo, during a trip to Washington D.C., publicly accused Burkina Faso of already hosting Wagner mercenaries and paying for them with mining concessions.115 This caused a diplomatic row between the two countries, with Burkina Faso summoning the Ghanaian ambassador in Ouagadougou in response.116 The fallout from the rift threatens to weaken two key pillar states of the Accra Initiative, a cooperative security mechanism comprising seven West African states.117 The initiative voted in late November 2022 to establish a joint task force to help combat the jihadi insurgency flowing across Burkina Faso’s borders. But with two of its key member states currently in a diplomatic tiff, it is unclear what progress has been made in forming such a task force. Ghana did eventually backtrack on the allegations and sent a high-level delegation to mitigate the diplomatic fallout of President Nana Akufo-Addo’s statements.118

If Wagner does deploy to Burkina Faso it would be a symptom of the country’s increased reliance on private military companies writ large. By using such companies, the unelected military junta in Burkina Faso ensures little to no accountability or transparency on the operations carried out by these companies. The junta in Ouagadougou has little incentive—or need—to provide updates to its populace on what any mercenary group or faction is doing inside Burkina Faso. This in turn helps foster public distrust of the regime. For instance, in Mali, the presence of Wagner has caused what ACLED describes as a “climate of fear,” wherein civilian journalists are afraid to report on the group or criticize its presence in the country out of a fear of potential reprisals.119 And as is clear from their performance elsewhere in Africa, private military companies can oftentimes leave countries worse off than when they arrived as they have historically prioritized the protection of resources, companies, and key personnel involved in resource extraction, as well as their own profit over the well-being of civilians or civilian infrastructure.120

Moreover, if a hypothetical future Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso is paid for with mining concessions, this would not only lead to the draining of state resources, but could also lead to the further militarization of Burkinabe society. In other West African conflicts, such as in Liberia and Sierra Leone, resources concessions to private military companies only perpetuated the cycle of violence as the industries in which concessions were granted themselves became more militarized.121 This dynamic is playing out now inside the Central African Republic, where Wagner has utilized increased violence, including assassinations of others involved in artisanal mining.122 In CAR, it has also used armed personnel to protect one of its shell companies involved in the mining and smuggling of diamonds out of the country.123 Worryingly, Burkina Faso is already well on the way to militarizing its society, having already mobilized and armed civilians as part of its VDP program.

Conclusions

The authors assess that given the current dynamics, a Wagner Group deployment to Burkina Faso is likely in the near-future. Burkina’s military ruler Ibrahim Traore—much like his predecessor, Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba—faces high internal pressure, particularly from certain segments within the Burkinabe military and among influential economic actors with interests in the mining and construction sectors, and external pressure, such as from Mali and Russia itself, to ally his country with the notorious private military company. Given the current ill-feeling of the junta in Ouagadougou against France, and indeed much of the West, it seems likely that any attempt at increased diplomatic pressure against Traore to move away to Russia and Wagner will fall on deaf ears. Unlike Damiba, who rebuffed such pressure, Traore is, in the authors’ assessment, much more likely to cave. The authors believe it is only a matter of time before Burkina Faso hires Wagner.

A Wagner deployment to Burkina Faso would further entrench Russian influence in Africa, complicate Western policy in West Africa, imperil regional counterterrorism cooperation, and bring about additional humanitarian concerns given Wagner’s reprehensible record, further aggravating Burkina Faso’s human rights situation, which is already dire.

This does not mean that any hiring of the Wagner Group would be the government’s main solution to securing and stabilizing the country. Traore’s main line of effort has been to mobilize the masses via the VDP. That said, upscaling the VDP program is no guarantee for success, and if the security situation in Burkina continues to deteriorate, Wagner may be one of the few options left for Traore to protect his own position and preserve the interests of economic or other political actors and related sectors. This is not dissimilar to what has historically occurred in other West African states utilizing PMCs such as Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Ouagadougou’s apparent consideration of hiring the Wagner Group is just a symptom of the broader hollowing of Burkinabe institutions that billions of dollars and tens of thousands of foreign troops deployed across the Sahel for almost a decade have failed to arrest. Burkina Faso’s dependence on citizen militias, PMCs, and PSCs is already highly damaging to the fabric of the country, by militarizing society, reducing accountability, and draining state resources. It is this environment that jihadi groups have found so fertile in Burkina Faso. Given that Wagner’s poor counterterrorism capabilities and heavy-handed tactics have made the jihadi problem worse in neighboring Mali, there is every likelihood that a deployment by the Russian private military company to Burkina Faso would also pour oil on the jihadi fire there.

Substantive Notes

[a] On December 21, 2022, Rybar claimed that “Rybar’s team managed to confirm that Wagner PMC employees are indeed on the territory of Burkina Faso, and the negotiations are close to completion.” Reliable local sources could not confirm the claim and stressed that any Wagner presence in the country would not have gone unnoticed. Rybar is part of Russia’s information warfare matrix. The communications and the special attention given to Burkina Faso may be an attempt to influence the information environment to create further tension between Burkina Faso and its Western partners. “Situation in the Sahel as of December 21, 2022” (translated from Russian), (Telegram), December 21, 2022; author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe security expert, December 2022; “Who runs the Rybar military telegram channel: The Bell investigation” (title translated from Russian), Bell, November 16, 2022.

[b] The Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) had previously reached an agreement with ousted leader Lt. Col. Paul Henri Sandaogo Damiba to hold elections by July 2024. “Transition au Burkina Faso : le Président en exercice de la CEDEAO satisfait de l’évolution de la situation,” Service d’Information du Gouvernement (SIG), July 24, 2022; “Coup d’État au Burkina : La CEDEAO demande le maintien du délai de juillet 2024 pour le retour à l’ordre constitutionnel,” Le Faso, September 30, 2022.

[c] Volontaires pour la défense de la patrie (Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland, or VDP) are local state-backed self-defense militiamen that support Burkina Faso’s regular forces in combating jihadi groups. Many VDP are recruited from preexisting self-defense groups such as the Koglweogo and Dozo.

[d] JNIM claimed the attack in a October 3, 2022, statement entitled “Economic blow and military coup in Burkina Faso.” The group claimed credit for creating the conditions that led to the September 30, 2022, coup, saying “the decisive economic blow caused an earthquake in the ranks of the Burkinabe arm which led to a military coup in the country.” Wassim Nasr, “#BurkinaFaso #JNIM revendique l’embuscade sur la route de #Djibo …,” Twitter, October 4, 2022.

[e] The Union of Truck Drivers of Burkina (UCRB) said in the wake of the incident that as many as 70 drivers remain unaccounted for. “Attaque de Gaskindé : ‘Plus de 70 chauffeurs routiers manquent à l’appel’ (UCRB),” Minute.bf, October 6, 2022.

[f] It is important to note that most of these pro-Russia demonstrations were simultaneously anti-France with demonstrators chanting anti-France slogans and calling for the withdrawal of French forces from Burkinabe territory. In October and November 2022, after the second coup, several demonstrations took place in front of the military base in Kamboinsin, where French special forces from Task Force Sabre had been stationed since 2009. According to data gathered by author (Nsaibia) for the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED); “France struggles to find a way through the confusion in Burkina Faso,” Africa Intelligence, October 12, 2022.

[g] When widespread looting and destruction of property are taken into account, the picture becomes even bleaker. JNIM militants in particular have incorporated a systematic ‘economic warfare’ into their strategy, which includes the destruction of security infrastructure—often through the use of explosives—government buildings, telecommunications installations, water pumping stations, power lines, schools, logistic and supply convoys (including transport trucks and fuel tankers), and other property. Authors’ tracking of jihadi activity in Burkina Faso.

[h] Damiba was eager to maintain good relations with Russia, which plays a key role in supplying Burkina Faso with military equipment, while at the same time maintaining French and U.S. intelligence assistance, French air and combat support when needed, and equipment from other countries such as Turkey and the Czech Republic. Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[i] Traore has retained and strengthened the Patriotic Watch and Defense Brigade (BVDP), created under Damiba, to assemble and coordinate VDP units at the local level. Traore has also reorganized the armed forces by restructuring the chain of command of the National Theater Operations Command (COTN), creating three additional military regions, and six rapid intervention battalions (BIR). The BIR is envisaged as a mobile and responsive force that could be deployed across Burkinabe territory. Here again, the VDP are assigned a prominent role as it is envisaged that the BIR will be composed of both soldiers and VDP. It appears that Traore will also rely on the section (or platoon) sized FORSAT (Special Anti-Terrorist Force) to retake areas controlled by militants. Similar to the BIR, FORSAT is composed of soldiers and VDP. It is envisaged that FORSAT will be “better trained, equipped, and organized,” including with armored vehicles and supported by helicopters and combat drones to intensify offensive operations, according to reports on local social media. “Burkina Faso : Création d’une Brigade de veille et de deux zones d’intérêt militaire dans le Sahel et l’Est,” Anadolu Agency, June 21, 2022; “Burkina : recrutement de 35 000 VDP communaux en plus des 15000 VDP nationaux,” Actualite.bf, October 25, 2022; “Burkina Faso: le président de la Transition, Ibrahim Traoré procède à une restructuration de l’armée,” Libre Info, November 16, 2022; “Burkina: le président de la transition, le capitaine Traoré, réorganise les forces armées,” November 16, 2022; “Le Président du Faso Ibrahim Traoré compte sur la FORSAT(Force spéciale anti-terroriste),” Faso Times (Facebook), October 24, 2022.

[j] The Popular Movement for the Resistance of Bam, a precursor of the VDP, was formed in October 2019 in the town of Kongoussi. “Insécurité dans la province du Bam : Les populations préparent la résistance,” Le Faso, October 6, 2019.

[k] JNIM’s Burkinabe branch and Ansaroul Islam emir Jafar Dicko addressed the Burkinabe people in a video the group released in response to the mobilization within Burkina Faso for the VDP initiative. He threatened “total war” including blockades on access roads to cities and towns, and along borders with neighboring countries. in order to suffocate Burkina Faso. Larmes des pauvres, “Dans une vidéo de 5’01’’ le chef la branche #Burkina-bé du #JNIM adresse …,” Twitter, November 28, 2022.

[l] At least seven of these regions, including the country’s two largest regions (Sahel and Est), can be considered heavily affected by the jihadi violence. In the four other regions in which the insurgency is present, jihadi activity has varied. For example, both Centre-Ouest and Hauts-Bassins saw a rapid increase in jihadi activity in 2022. In Sud-Ouest, the level of jihadi activity was fairly constant at either a low or moderate level. In the Centre-Sud, on the other hand, activity could be best described as sporadic.

[m] This expansion of activities during Damiba’s rule was particularly pronounced in Nayala and Banwa provinces in Boucle du Mouhoun region, Koulpelogo and Boulgou provinces in Centre-Est region, Boala department in Namentenga province and Kaya department in Sanmatenga province in Centre-Nord region, Sanguie and Sissili provinces in Centre-Ouest region, and Houet, Kenedougou, and Tuy provinces in Hauts-Bassins region.

[n] This has forced the Burkinabe military to supply towns and villages from the air, including Djibo, Sebba, Solhan, and Tin-Akoff in the Sahel region, where the risk of famine is imminent. “Sebba (région du Sahel) : Confrontées à la famine, les femmes marchent pour exprimer leur ras-le-bol,” Le Faso, September 18, 2022; “Il Etati Temps !” Pays, October 6, 2022; “Burkina : la population de Solhan a faim et crie au secours,” minute.bf, December 13, 2022.

[o] Since that raid, Côte d’Ivoire has been targeted at least 15 additional times by JNIM, including the use of four improvised explosive devices (IEDs), with an additional three IEDs that either failed to detonate or were defused. However, reported jihadi attacks in the country have slowed dramatically since March 2022. According to data compiled by author (Weiss) for FDD’s Long War Journal.

[p] Though the current junta in Ouagadougou kicked out several French officials and institutions, in addition to harboring a more generalized anti-French attitude, France still housed at least 400 special forces soldiers in the country as of mid-January 2023. As noted higher, on January 18, 2023, the Burkina junta demanded French troops leave within a month. See “French minister says France still committed to Burkina Faso despite tension,” Reuters, January 11, 2023.

[q] After RFI reported on abuses committed by the Malian Armed Forces (FAMA), the Malian transition government spokesperson compared RFI to Rwanda’s Radio Mille Collines, which played a significant role in inciting the Rwandan genocide. “Malian junta orders French broadcasters RFI, France 24 off air,” RFI, March 17, 2022.

[r] A founding member of JNIM, al-Murabitoon was itself the result of a merger of two other al-Qa`ida-affiliated groups in the Sahel: the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa and Katibat al-Mulathameen.

[s] The error was apparently geographical. Kompienbiga and Zourma share the same coordinate numbers, albeit in eastern and western direction, respectively, on the longitudinal axis. Kompienbiga is located in Kompienga Province of Est Region and Zourma in Boulgou Province of Centre-Est Region.

Citations

[1] “Burkina Faso ends French military accord, says it will defend itself,” Reuters, January 23, 2023; “Le Burkina Faso a acté le départ de l’armée française de son territoire,” Agence d’Information du Burkina, January 21, 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] “Burkina Faso requests French ambassador withdrawal, Paris says,” Al Jazeera, January 4, 2023.

[4] “Au Burkina Faso, une nouvelle manifestation contre la présence française,” France 24, January 20, 2023.

[5] “Burkina Faso’s coup and political situation: All you need to know,” Al Jazeera, October 5, 2022.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “France completes withdrawal from Mali as last army unit pulls out,” EuroNews, August 16, 2022.

[8] Danielle Paquette, “Wagner mercenaries have landed in West Africa, pushing Putin’s goals as Kremlin is increasingly isolated,” Washington Post, March 9, 2022.

[9] Jack Detsch and Amy Mackinnon, “Burkina Faso Could Be Next for Russia’s Wagner Group, U.S. Intel Fears,” Foreign Policy, July 27, 2022; Sam Mednick, “Russian role in Burkina Faso crisis comes under scrutiny,” Associated Press, October 18, 2022.

[10] “US Warns Burkina Faso Coup Leaders On Russia,” Barron’s, October 4, 2022; “Burkina Faso not planning to hire Russian fighters like Mali – U.S. diplomat,” Reuters, October 26, 2022; “About the rumors about the appearance of Wagner PMC in Burkina Faso” (translated from Russian), Rybar (Telegram), December 18, 2022.

[11] Philip Obaji, “A deal between the Russian Wagner Group and Burkina Faso is near …,” Twitter, January 26, 2023.

[12] “Burkina Faso : Le groupe Wagner a posé ses valises à Ouagadougou,” Informateur, January 3, 2023; “Des mercenaires de Wagner ont-ils débarqué au Burkina Faso?” Jeune Afrique, January 6, 2023.

[13] “1960 – 2022: The long history of coups d’état in Burkina Faso,” Africa News, January 25, 2022.

[14] Omega Rakotomalala and Farouk Chothia, “Capt Ibrahim Traoré: Burkina Faso’s new military ruler,” BBC, October 3, 2022.

[15] “Ibrahim Traoré appointed President of Burkina Faso,” Africa News, October 6, 2022.

[16] Ibid.

[17] “Deposed Damiba resurfaces in Lomé,” APA News, October 3, 2022.

[18] Sam Mednick and Arsene Kabore, “Burkina Faso coup leader says vote still expected by 2024,” Associated Press, October 3, 2022; “61e sommet de la CEDEAO : le Mali et le Burkina soulagés, grise mine d’un mois pour la Guinée,” aOuaga, July 5, 2022.

[19] “Un convoi de ravitaillement à destination de la ville de Djibo a été la cible d’une attaque lâche et barbare …,” Service d’Information du Gouvernement, September 27, 2022.

[20] “Five Kilometres of Destruction: Satellite Imagery Reveals Extent of Damage to Civilian Convoy in Burkina Faso,” Bellingcat, November 18, 2022.

[21] “Burkina Faso: ‘crise interne à l’armée’, discussions en cours,” VOA Afrique, September 30, 2022; “Burkina Faso : qui sont les ‘Cobras’, ces militaires qui font trembler le régime de Damiba?” Jeune Afrique, September 30, 2022.

[22] Henry Wilkins, “Why Burkina Faso Protesters Waved Russian Flags in French Embassy Attack,” Voice of America, October 6, 2022.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Jason Burke, “Burkina Faso coup fuels fears of growing Russian mercenary presence in Sahel,” Guardian, October 3, 2022.

[25] All Eyes on Wagner, “Après le rat, une nouvelle animation où le groupe #WagnerGroup apparaît …,” Twitter, January 14, 2023.

[26] “Au Burkina Faso, une nouvelle manifestation contre la présence française;” “A banner of Russian President Vladimir Putin is seen during a protest to support …,” Olympia de Maismont/AFP via Getty Images, January 20, 2023; “A banner of the Burkina Faso President Captain Ibrahim Traore is seen during a protest …,” Olympia de Maismont/AFP via Getty Images, January 20, 2023.

[27] Edward Mcallister, “Who is Ibrahim Traore, the soldier behind Burkina Faso’s latest coup?” Reuters, October 4, 2022.

[28] “Burkina coup-makers accuse France of supporting counterattack,” Al Jazeera, October 1, 2022.

[29] Ibid.

[30] “Burkina Faso : Le groupe Wagner a posé ses valises à Ouagadougou;” “Des mercenaires de Wagner ont-ils débarqué au Burkina Faso?”

[31] “Burkina Faso army says it has deposed President Kabore,” Al Jazeera, January 25, 2022.

[32] Sam Mednick, “Soldiers declare military junta in control in Burkina Faso,” Associated Press, January 24, 2022.

[33] “61e sommet de la CEDEAO;” “Transition au Burkina Faso : le Président en exercice de la CEDEAO satisfait de l’évolution de la situation,” Service d’Information du Gouvernement (SIG), July 24, 2022; “Coup d’État au Burkina : La CEDEAO demande le maintien du délai de juillet 2024 pour le retour à l’ordre constitutionnel,” Le Faso, September 30, 2022.

[34] Natasha Booty, “Mali and Burkina Faso: Did the coups halt jihadist attacks?” BBC, July 30, 2022.

[35] Rachel Chason and Borso Tall, “Burkina Faso massacre highlights a strengthening insurgency,” Washington Post, June 16, 2022; Anne Mimault and Thiam Ndiaga, “Eleven soldiers dead, 50 civilians missing after Burkina Faso convoy attack,” Reuters, September 27, 2022.

[36] Caleb Weiss, “Jihadist attacks flow into littoral West Africa,” FDD’s Long War Journal, December 3, 2021.

[37] “Burkina : les nouveaux ‘comités locaux de dialogue pour la paix’ suscitent des questions,” RFI, April 15, 2022.

[38] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[39] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, March 2022.

[40] Clionadh Raleigh, Andrew Linke, Håvard Hegre, and Joakim Karlsen, “Introducing ACLED-Armed Conflict Location and Event Data,” Journal of Peace Research 47:5 (2010): pp. 651-660.

[41] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[42] Agnès Faivre, “Au Burkina Faso, la ‘reconquête’ promise par les putschistes se fait attendre,” Libération, September 1, 2022.

[43] “Paul-Henri Damiba a un Activiste de Bobo : ‘Si vous êtes réellement fort (…), faites votre coup d’Etat et gérez le pays comme vous voulez,’” Pays, May 23, 2022.

[44] Pierre-Elie de Rohan Chabot, “France to provide Burkina Faso with military and financial support,” Africa Intelligence, September 27, 2022.

[45] “Coopération France-Burkina : Bientôt 15 millions d’euros pour venir en aide à l’Etat Burkinabè,” Le Faso, September 29, 2022.

[46] “France announces military withdrawal from Mali,” DW, February 17, 2022; “France not ruling out pulling special forces from Burkina,” Local, November 20, 2022.

[47] “Burkina Faso : Le capitaine Ibrahim Traoré va déclarer une ‘guerre totale’ en 2 plans contre les terroristes,” Afrik Soir, December 2, 2022.

[48] “Recrutement de VDP : Plus de 90.000 inscrits,” Burkina24, November 24, 2022.

[49] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[50] “Vote de la loi pour le recrutement des volontaires pour la défense de la patrie,” VOA Afrique, January 24, 2022; “Insécurité dans la province du Bam : Les populations préparent la résistance,” Le Faso, October 6, 2019.

[51] “The Volunteers for the Defense of the Homeland,” Clingendael, March 9, 2021.

[52] Héni Nsaibia and Caleb Weiss, “Ansaroul Islam and the Growing Terrorist Insurgency in Burkina Faso,” CTC Sentinel 11:3 (2018).

[53] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State kills hundreds of civilians in northern Mali,” FDD’s Long War Journal, March 25, 2022.

[54] Héni Nsaibia and Caleb Weiss, “The End of the Sahelian Anomaly: How the Global Conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qa`ida Finally Came to West Africa,” CTC Sentinel 13:7 (2020).

[55] “Actor Profile: The Islamic State Sahel Province,” ACLED, January 13, 2023.

[56] Ibid; Eleanor Beevor, “JNIM: A strategic criminal actor,” Global Initiative, August 2022; also based on authors’ own analysis and data of JNIM attacks and operations across Burkina Faso.

[57] “Ten soldiers killed, 50 wounded in attack on Burkina Faso army base,” Reuters, October 24, 2022; Héni Nsaibia, “Adding to the post-coup (2) state of counterinsurgency, yesterday’s attack in Djibo is the …,” Twitter (Menastream), October 25, 2022.

[58] Roméo Koeta, “#Burkina-#insécurité: Un convoi de camions fournisseurs, de retour, de la mine d’or d’Essakane …,” Twitter, December 9, 2022.

[59] “Burkina Faso: 37 dead in September attack on Gaskinde – army,” Africa News, October 5, 2022.

[60] Héni Nsaibia, “After consolidating control, maintaining a blockade on Pama town, and transforming Kompienga Province …,” Twitter (Menastream), October 14, 2022.

[61] Ibid.

[62] Ibid.

[63] “Ivory Coast: 16 dead in Grand Bassam beach resort attack,” BBC, March 14, 2016.

[64] “Côte d’Ivoire: Attaque de Kafolo, la Nation re 14 militaires tués, la liste complète des victimes,” Koaci, July 2, 2020.

[65] Based on authors’ tracking and ACLED data.

[66] According to data compiled by author (Weiss) for FDD’s Long War Journal.

[67] Caleb Weiss, “Islamic State claims first attacks inside Benin,” FDD’s Long War Journal, September 17, 2022.

[68] According to data compiled by author (Weiss) for FDD’s Long War Journal.

[69] “Benin says in talks with Rwanda over logistical aid to counter Islamist threat,” Reuters, September 10, 2022.

[70] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[71] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, October 2022.

[72] According to data gathered by author (Nsaibia) for the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED).

[73] “Alerte – Au moins 70 véhicules incendiés sur l’axe Dori-Ouaga, ‘une perte de 5 milliards’. (Transporteurs),” Radio Omega, December 10, 2022.

[74] “Burkina Faso government suspends broadcast of France’s RFI,” Al Jazeera, December 4, 2022.

[75] “Malian junta orders French broadcasters RFI, France 24 off air,” RFI, March 17, 2022.

[76] “Institut Français in Ouagadougou vandalised in Burkina Faso coup protests,” Africa News, October 13, 2022; Sam Mednick and Arsene Kabore, “Protesters attack French Embassy in Burkina Faso after coup,” Associated Press, October 1, 2022; “Civic space further restricted after second military coup,” Civicus, December 14, 2022.

[77] “Les forces françaises pourraient quitter le Burkina Faso,” DW, November 21, 2022; “Internal briefing of the Burkinbe Armed Forces, Point De Situation Du 12 Au 13 Oct 2022,” October 13, 2022, obtained by author (Nsaibia).

[78] “Le Burkina expulse deux présumés espions français,” Agence d’Information du Burkina (AIB), December 21, 2022.

[79] “Mali : les deux militaires français relâchés,” Jeune Afrique, September 16, 2022.

[80] “Burkina Faso government expels senior U.N. official,” Reuters, December 23, 2022.

[81] “Paris says Burkina Faso requested withdrawal of French ambassador,” Reuters, January 4, 2023; “France backs envoy despite Burkinabe pressure for withdrawal,” Al Jazeera, January 5, 2023.

[82] “Burkina Faso : la France rappelle son ambassadeur pour ‘consultations’ après l’annonce du départ de ses troupes du pays,” Monde, January 26, 2023.

[83] “Terrorisme au Burkina-Mali : Ibrahim Traoré et Assimi Goïta s’engagent pour une lutte commune,” Afro impact, November 3, 2022.

[84] “Burkina Faso, Russia keen to strengthen mutually beneficial cooperation,” North Africa Post, September 26, 2022.

[85] “Burkina Faso: Ilyushin II-76’s mysterious arrival in the middle of a coup,” Africa Report, October 20, 2022.

[86] “Le Burkina n’exclut pas de réexaminer ses rapports avec la Russie,” VOA Afrique, October 31, 2022.

[87] “Exclusif – Burkina Faso : le voyage secret du Premier ministre à Moscou,” Jeune Afrique, December 10, 2022.

[88] Ibid.

[89] “Burkina Faso : le boom des compagnies de sécurité,” Jeune Afrique, March 7, 2014; “Le business de la sécurité est en pleine expansion,” Africa Intelligence, May 9, 2018.

[90] Caleb Weiss, “Al Murabitoon shows Romanian hostage in new video,” FDD’s Long War Journal, September 2, 2015.

[91] Based on authors’ research of Omega Consulting and its affiliated social media.

[92] “Our training facility in Ouagadougou,” Omega Consulting (Facebook), April 11, 2018.

[93] “Lutte contre le terrorisme : des ‘mercenaires’ ukrainiens et bulgares au Burkina,” Courrier Confidentiel, August 10, 2020.

[94] Author (Nsaibia) personal communications, Burkinabe military source, August 2020.

[95] “Lutte contre le terrorisme : des ‘mercenaires’ ukrainiens et bulgares au Burkina.”

[96] “Attaque à Kompienbiga (Est) : les agents du campement ont flairé le danger,” Agence d’Information du Burkina (AIB), August 30, 2018.

[97] “Lutte contre le terrorisme : des ‘mercenaires’ ukrainiens et bulgares au Burkina.”

[98] Ibid.

[99] Nadoun Coulibaly and Vincent Duhem, “Arms sales in Burkina Faso: Rafi Dermardirossian, the fall of the falcon,” Africa Report, May 20, 2022.

[100] Andrew McGregor, “Russian Mercenaries and the Survival of the Sudanese Regime,” Jamestown Foundation, February 6, 2019.

[101] Ladd Serwat, Héni Nsaibia, Vincenzo Carbone, and Timothy Lay, “Wagner Group Operations in Africa: Civilian Targeting Trends in the Central African Republic and Mali,” ACLED, August 30, 2022.

[102] Ibid.

[103] Ibid.

[104] Ilya Barabanov and Nader Ibrahim, “Wagner: Scale of Russian mercenary mission in Libya exposed,” BBC, August 11, 2021.

[105] Tim Lister and Sebastian Shukla, “Russian mercenaries fight shadowy battle in gas-rich Mozambique,” CNN, November 29, 2019.

[106] Peter Fabricius, “Wagner private military force licks wounds in northern Mozambique,” Daily Maverick, November 29, 2019; Peter Fabricius, “‘SA private military contractors’ and Mozambican airforce conduct major air attacks on Islamist extremists,” Daily Maverick, April 9, 2020.

[107] “US army confirms Russian mercenaries in Mali,” France 24, January 21, 2022.

[108] John Irish and David Lewis, “EXCLUSIVE Deal allowing Russian mercenaries into Mali is close – sources,” Reuters, September 13, 2021.

[109] Elian Peltier, Mady Camara, and Christiaan Triebert, “‘The Killings Didn’t Stop.’ In Mali, a Massacre With a Russian Footprint,” New York Times, May 31, 2022.

[110] “Debunking the Malian Junta’s Claims,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, April 12, 2022.

[111] Wassim Nasr, “How the Wagner Group Is Aggravating the Jihadi Threat in the Sahel,” CTC Sentinel 15:11 (2022).

[112] Ibid.

[113] “Wagner Group Operations in Africa.”

[114] Nasr.

[115] “[Remarks of] Secretary Antony J. Blinken and Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo Before Their Meeting,” U.S. State Department, December 14, 2022; Kent Mensah, “Ghana Says Burkina Faso Paid Russian Mercenaries with Mine,” Voice of America, December 15, 2022.

[116] “Burkina Faso summons Ghana envoy over president’s claim on Wagner,” Al Jazeera, December 16, 2022.

[117] Kent Mensah, “Can the Accra Initiative prevent terrorism in West African coastal states?” Africa Report, November 29, 2022.

[118] “Wagner fallout: Ghanaian delegation in Burkina Faso,” APA News, December 22, 2022; “Ghana Repairs Rift With Burkina Faso After Wagner Claims,” VOA, December 22, 2022.

[119] “Wagner Group Operations in Africa.”

[120] Mpako H. Foaleng, “Private Security in Africa: Manifestation, Challenges and Regulation,” Institute for Security Studies, Monograph No. 139, chapter 3, November 2007.

[121] Ibid.

[122] Mary Ilyushina and Francesca Ebel, “Russian mercenaries accused of using violence to corner diamond trade,” Washington Post, December 6, 2022.

[123] Jason Burke and Zeinab Mohammad Salih, “Russian mercenaries accused of deadly attacks on mines on Sudan-CAR border,” Guardian, June 21, 2022; “CAR: Prigozhin’s Blood Diamonds,” All Eyes on Wagner, December 2022.