Abstract: With the explosive growth of banditry in northwestern Nigeria in recent years, there has been growing speculation among Nigerian and international observers that these criminal insurgents are receiving support from or otherwise converging with jihadis based in the country’s northeast. However, a lack of open-source data on the inner workings of both banditry and Nigeria’s jihadi insurgencies have precluded detailed analysis of this potential “crime-terror nexus.” Drawing on the authors’ extensive fieldwork across Nigeria’s northern conflict zones in 2021 and early 2022, including exclusive interviews with both bandits and jihadi defectors, this article provides the first in-depth examination of the links between Nigeria’s bandits and jihadi organizations. While there are many reasons to expect that Nigeria’s bandits and jihadis would cooperate and that jihadis would recruit bandits to their cause, the authors show how this has not been the case. The authors argue that Nigeria’s bandits are too fractious and too powerful for jihadis to easily coopt them and that the bandits’ lack of ambitious political objectives—and the significant differences in the modus operandi of bandits and jihadis—means that jihadism holds little intrinsic appeal for them. However, jihadi groups have taken advantage of instability in the northwest enabled by the bandits to establish small enclaves in the region that they are likely to sustain as long as they can maintain a modus vivendi with local bandit gangs.

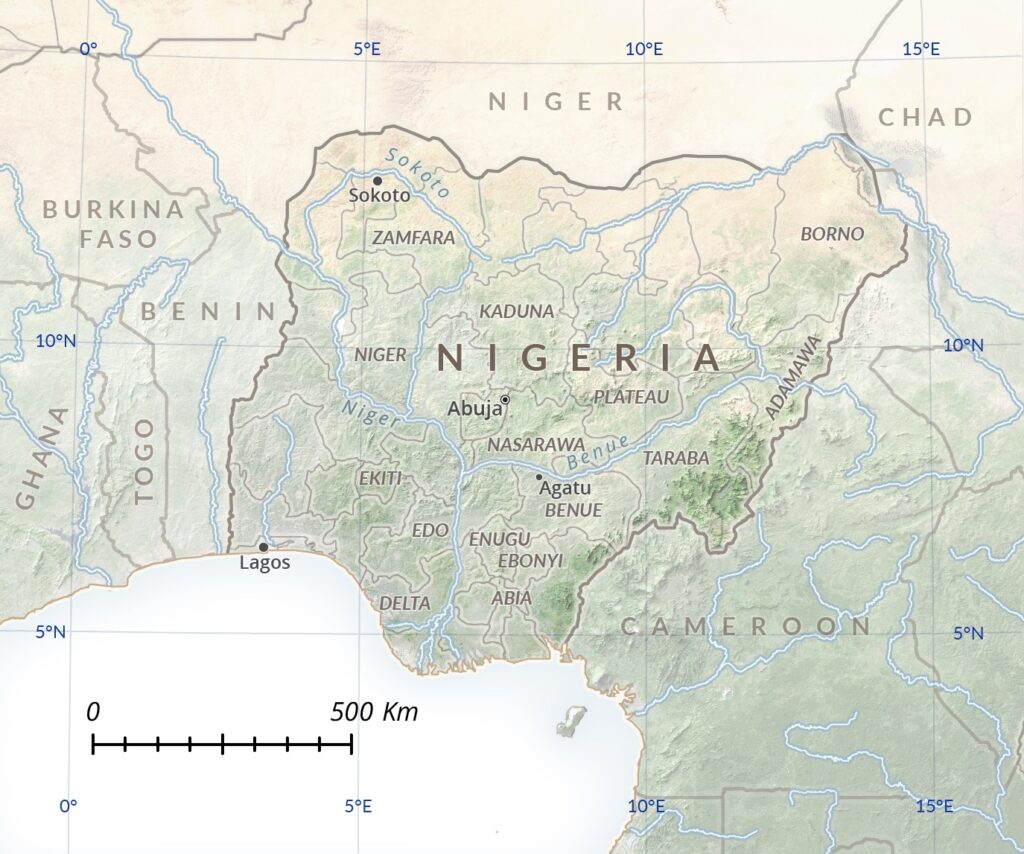

Northern Nigeria is presently suffering from two devastating conflicts. In the Lake Chad basin in the country’s northeast, a 13-year jihadi insurgency that has killed nearly 350,0001 and displaced several million rages with no end in sight.2 The faction of “Boko Haram” known as Jama‘at Ahl al-Sunna li-Da‘wa wal-Jihad (JAS) is in disarray after the killing of its longtime leader Abubakar Shekau in May 2021, but it is not yet a totally spent force. The rival Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP) faction, meanwhile, remains strong and controls large swathes of rural Borno on all sides of the capital, Maiduguri.3

In northwestern Nigeria,a a complex and volatile insurgency is roiling a region the size of the United Kingdom, leading, shockingly, to more civilian deaths in 2021 than the conflict in the northeast.4 Well-armed bandits are terrorizing communities and wearing down overstretched security forces, getting rich through criminal activity such as kidnapping for ransom, and assuming de facto sovereignty over swathes of the region. Most of the militants are Fulani herdsmen who claim to be fighting to redress the government’s neglect of pastoralist communities.5 But their insurgency, to the extent the violence can be classified as such, is fractured into dozens of competing bandit groups loosely organized around warlords of varying power.6

Though these two conflicts are distinct, Nigerians fear that the insurgencies will overlap and jihadis will cooperate with bandits in a classic example of a “crime-terror nexus” or possibly convert the bandits (who are mostly Sunni Muslim) into jihadis themselves.b While there is a voluminous academic literature on the jihadi landscape in Nigeria, far less has been written about Nigeria’s banditry crisis, which contributes to a hazy understanding of this potential crime-terror nexus.c What has been written on the bandits (including by these authors) has generally included only a few details regarding how bandits and jihadis interact. With such limited data to draw on, analysts have been left to speculate about the interactions between bandits and jihadis. For example, in a recent article, Jacob Zenn and Caleb Weiss suggest that the “Boko Haram” splinter group Ansaru is liable to integrate into conflict-torn communities, as al-Qa`ida franchises have elsewhere in West Africa, in order to expand throughout the northwest, potentially producing an “arc of insurgency” in West Africa.7 As Zenn and Weiss note, jihadis have successfully coopted bandits in other West African countries such as Burkina Faso, a process Héni Nsaibia of the Armed Conflict Location Event Database (ACLED) dubbed “a jihadization of banditry.” Nsaibia argues that jihadis may provide more than just money or weapons to criminals: “From the perspective of armed bandits, rallying militant Islamist groups could also serve as a means to ‘morally’ justify plundering and pillaging as part of a greater cause.”8

Concerns of a crime-terror nexus in Nigeria are logical and merit serious consideration. This study aims to begin filling the data gaps that have so far hindered such consideration by offering detailed insights into the overlapping worlds of banditry and jihadism based on the authors’ extensive fieldwork. Each of the authors has traveled widely across northern Nigeria, accessing conflict zones that have otherwise been off-limits to researchers and gaining exclusive interviews throughout 2021 and early 2022 with some of the most powerful bandits, former jihadi commanders, and residents of jihadi enclaves, among others.

In assessing bandit-jihadi relations, the authors use the framework of Erik Alda and Joseph L. Sala,9 who lay out three stages of potential nexus between criminals and terrorists:

Coexistence, in which criminals and terrorists “coincidentally occupy and operate in the same geographic space at the same time.”10

Cooperation, in which criminals and terrorists “decide that their mutual interests are both served, or at not least severely threatened, by temporarily working together.”11

Convergence, in which “each [ie criminals and terrorists] begins to engage in behavior(s) that is/are more commonly associated with the other.”12

The authors find that jihadis have coexisted and intermittently cooperated with bandits in the northwest, with cooperation being limited to short-term, mutually beneficial exchanges of material or skills (for example, jihadis offering training in explosives or advice on negotiating kidnap ransoms). However, there has not been a convergence of banditry and jihadism in a manner analysts might expect. Bandits have begun conducting certain types of operations, namely mass kidnappings, that are generally associated with Nigerian jihadi groups, but this is not necessarily a result of sustained cooperation between bandits and jihadis (as discussed later in the article). With regard to a larger strategic and/or ideological convergence, the authors find evidence that jihadis have converted to bandits, but they have not seen the process work in the opposite direction, with no major bandit ever electing to become a jihadi and remaining one.d The authors assess there are several reasons behind jihadis’ failure to coopt bandits:

Nigeria’s bandits have grown so powerful that they are not in desperate need of cooperation with jihadis (let alone a need to convert to jihadism).

The bandits’ gangs are so numerous and loosely organized, and bandits fight among each other so frequently over parochial issues, that jihadis would have difficulty coopting more than a handful of gangs at a time.

Additionally, differences in the modus operandi and objectives of bandits and jihadis render jihadism unappealing to bandits: While bandits have no coherent political agenda and have managed to grow rich and powerful by plundering Muslim communities in the northwest, jihadis are deeply committed to a revolutionary political project and, particularly in the case of ISWAP and Ansaru, seek to gain popular support from the sorts of vulnerable Muslim communities that bandits prey on.

Nevertheless, the uncommon conversion of bandits to jihadis has not precluded jihadis from benefiting from operating alongside the bandits. Jihadis have established sanctuaries in the northwest—Ansaru has an enclave in Kaduna state, and JAS and possibly ISWAP are regrouping in Niger state. However, these benefits are not without challenges. Jihadis must navigate complex relationships with powerful bandit gangs that are disinterested if not outright averse to jihadi ideology.

This article will attempt to address the question of bandit-jihadi relations through the perspectives of both bandits and jihadis. To this end, the article begins with a general overview of both Nigeria’s jihadis and bandits. Then, the authors explain the factors that would, theoretically, push bandits and jihadis to cooperate if not converge. In the subsequent section, the authors analyze why such convergence has, in fact, been lacking, focusing on four primary factors that hinder greater bandit-jihadi cooperation. In the next two sections, the authors offer case studies: first from the perspective of bandits, examining several powerful warlords as a way of adding nuance to the question of what bandits do (and do not) hope to gain from working with jihadis; and second from the perspective of jihadis, assessing the degree to which Nigeria’s three primary jihadi outfits (JAS, ISWAP, and Ansaru) have cooperated with and coopted bandits in their attempted efforts at expansion in the northwest. The article concludes with a call for greater nuance in discussions of the crime-terror nexus, both within West Africa and globally, while the authors also caution Nigerian and international policymakers not to rely heavily on counterterrorism paradigms in approaching the escalating crisis in Nigeria’s northwest.

Conflict Actors in Northern Nigeria: Jihadis and Bandits

Jihadis

The three primary jihadi outfits that operate in Nigeria today—JAS, ISWAP, and Ansaru—each emerged from the original JAS or “Boko Haram” that gradually evolved from a mass political preaching movement into a jihadi insurgency between approximately 2002 and 2009. At no point in history have the insurgents officially called themselves “Boko Haram.” This name, which translates loosely from Hausa (the lingua franca of northern Nigeria) into English as “Western education is haram (forbidden),” was initially a pejorative used by the movement’s detractors13 and has since become the popular name among Nigerians and many analysts for Shekau’s JAS faction if not all jihadis in Nigeria.e For purposes of this article, “Boko Haram” is used to refer to the movement—first a salafi preaching movement and then a violent jihadi organization starting in 2009—up to the point of its splintering in 2015-2016.f By 2016, two distinct factions had emerged that remain active today: the faction of the now late Abubakar Shekau, referred to as JAS (the official name for the “Boko Haram” group since 2009) and now led by one “Bakura” as described below; and the ISWAP faction, officially recognized by the Islamic State and originally led by Abu Musab al-Barnawi (who himself likely died in late 2021, only a few months after Shekau).g A third faction that split from “Boko Haram” back in 2012, Ansaru, will also be discussed in detail toward the end of this article.

Jihadi violence in Nigeria has historically been concentrated in the country’s northeast, particularly Borno state. The “Boko Haram” movement formed in the Borno state capital, Maiduguri, in the early 2000s and built its strongest networks and popular base in that city and elsewhere in Borno.14 As a salafi preaching movement and later salafi-jihadi insurgency, “Boko Haram” naturally disavowed any ethnonationalist or regionalist agenda and saw itself as a vehicle for Muslims across Nigeria and West Africa broadly to advance an Islamic revolution. The group’s founder, Muhammad Yusuf, gained admirers across Nigeria and in neighboring countries thanks to the distribution of his sermons via cassette and mobile phone.h While both JAS and ISWAP are to this day believed to be largely Kanuri (the majority ethnic group in Borno, though a minority elsewhere in the north), each group’s commanders and rank-and-file alike include other ethnicities such as Hausa, Fulani, and Buduma.15

In the first years after the launch of the group’s violent jihad in 2009, “Boko Haram” maintained attack cells in various parts of northern and central Nigeria. Most notably, the group conducted a suicide vehicle-borne IED attack against the U.N. headquarters building in the federal capital, Abuja, in August 2011 and coordinated bombings in the northern metropolis of Kano in January 2012. However, by 2014, the group was confined to its strongholds in the northeast, in part due to security operations and infighting.16 Since 2014, nearly all claimed jihadi activity in Nigeria has occurred in the northeast, mostly in Borno state as well as in parts of neighboring Yobe and Adamawa and in adjacent communities in Cameroon, Chad, and the Republic of Niger, a region often referred to as the Lake Chad basin. Consequently, any sustained jihadi operations in northwestern Nigeria would represent the most notable expansion of the original “Boko Haram” conflict since the mid-2010s.

Bandits

Banditry is a loosely defined concept, but generally speaking, Nigeria’s bandits are rural gangs that engage in criminal activities such as cattle rustling, looting of villages, extortion of local communities, and kidnapping for ransom. Banditry has been widespread throughout the country but has grown most acute in the northwest, particularly Zamfara state, in the past decade.

There are as many as 30,000 banditsi spread over 100 gangs operating in northwestern Nigeria, the largest likely not fielding much more than 2,000 fighters.j Bandits’ alliances shift frequently as new feuds erupt and short-term interests drive erstwhile rivals to cooperate.17 The most powerful gang leaders operate as warlords, exercising de facto sovereignty over swathes of the countryside.18 Even the largest gangs are loosely organized, however, and gangs frequently fracture, either by mutual agreement or violent conflict.19

Many bandits are Fulani herdsmen who claim to be fighting in protest of the government’s mistreatment of herders, though members of other ethnic groups are also present in the gangs.20 While many bandits took up arms with genuine grievances against the state, they have since developed a more criminal modus operandi.21 Rather than channel their grievances into a rebellion against the government, the bandits primarily attack ordinary villagers and travelers and feud with rival gangs.k That said, notions of ethnic solidarity or chauvinism sometimes drive bandits’ behavior, with some bandits conducting retaliatory attacks against Hausa communities that have killed Fulani herders.22 The ethnic dimension of banditry fluctuates in salience, with bandits making more of an effort to assume the mantle of ethnic militants at times of heightened Hausa-Fulani tensions but otherwise operating as profit-maximizing militants.23 Religion, however, is not the most salient dimension of banditry in the northwest, as both the bandits and the large majority of their victims in the northwestern states are Sunni Muslim.

Theories of Bandit-Jihadi Cooperation and Convergence

Northwestern Nigeria—the domain of Nigeria’s bandits—seems, superficially, vulnerable to jihadi expansionism. The northwest is neither geographically nor socially isolated from the country’s northeast or other jihadi hotspots in West Africa, and the region lacks robust state institutions or adequate security forces that might serve as a bulwark against jihadis. The northwestern states are geographically proximate to northeastern Nigeria and share a long, under-policed border with the Republic of Niger, where the al-Qa`ida-linked Jama’at Nasr al Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) and the Islamic State’s West Africa Province Greater Sahara branch (ISWAP-Greater Sahara), colloquially known as the Islamic State in Greater Sahara (ISGS), operate.l The northwest’s terrain is conducive to insurgency owing to its vast forests, some of which stretch to the northeast.24 Further, the northwest’s population is mostly Sunni and the region shares many of the socioeconomic and cultural factors that contributed to “Boko Haram’s” rise in the northeast such as widespread poverty, low levels of education, a corrupt political elite, and a strong salafi movement.25 Nigeria’s security forces are largely absent in the northwestern countryside while government institutions, infrastructure, and services ranging from schools to tarmacked roads also tend to be concentrated in urban areas, leaving many villages without a tangible state presence. Additionally, trade, migration, and conquest have connected communities in the northwest with those in the northeast, and the broader Sahel, since the pre-colonial era, such that a good number of bandits and jihadis share a common ethnicity.m

Given these factors, northwestern Nigeria would seem a likely spot for bandits and jihadis to work together as the latter seek to establish a presence outside of the northeast. Theoretically, both jihadis and bandits could see it in their interests to seek a convergence that leads bandits to more closely resemble jihadis, as seen elsewhere in the Sahel. For jihadis, the benefits of recruiting bandits into their fold are obvious: Coopting existing militant networks is one way for jihadi organizations to expand. ISWAP, the strongest jihadi group in Nigeria today, no doubt seeks to eventually expand beyond its stronghold in the northeast to wage an insurgency across northern Nigeria, where most of the country’s roughly 100 million Muslims live. Ansaru, meanwhile, has been based in the northwest since at least the mid-2010s while JAS is now likely also regrouping in the region (described in the subsequent section on JAS). For both of these groups, then, coopting bandits would be a means of securing their base of operations by becoming the dominant local militant group.

For bandits, convergence into jihadism also seems like a logical evolution in some ways. The bandits are Sunni Muslims who harbor grievances against the state (like jihadis). Unlike those recruited from “civilian” life into the ranks of jihadi organizations, bandits are already living in the bush as wanted militants, thus presumably removing many of the disincentives to joining a jihadi organization. Finally, as Nsaibia notes, jihadism offers bandits the chance to justify their militant activity as part of a “higher cause” that is religiously ordained—indeed obligatory.26

However, in reality, jihadis have mostly failed to coopt bandits in Nigeria. Bandits and jihadis have coexisted in the northwest, as the experience of Ansaru and more recently JAS attest. Bandits and jihadis have also occasionally cooperated, as the subsequent sections will show; such cooperation has included jihadis providing bandits with weapons,27 training bandits in the use of certain weaponry, or (most notably) providing manpower to certain gangs to conduct kidnappings or attack rival bandits. However, not only have jihadis largely failed to coopt bandits, but, as will be outlined, on several occasions jihadis have abandoned their jihad to become bandits themselves. Hence, there has been a degree of convergence between bandits and jihadis in Nigeria, but in a manner that strengthens bandits more than jihadis.

The next section lays out the structural impediments to greater bandit-jihadi cooperation and convergence. Subsequent sections add detail and nuance to this analysis of limited bandit-jihadi cooperation by profiling individual bandit commanders and their complex relationships with jihadis as well as the efforts of Nigeria’s three primary jihadi factions to expand into the bandit-dominated northwest.

Impediments to Jihadi Expansion in Northwestern Nigeria

The Challenges of Jihadis’ Cooperation with Bandits

In broad terms, there are four primary impediments to jihadis’ cooperation with and/or cooptation of bandits:

The fractiousness of the bandits

The power of the bandits

Differing political objectives among bandits and jihadis

Differences in the modus operandi of jihadis and bandits

Fractiousness of bandits: There cannot be an alliance between “Boko Haram and the bandits,” as one often hears fears of in Nigeria, because “the bandits” are not a coherent or unified bloc (nor is “Boko Haram,” for that matter). As noted earlier, the bandits are loosely organized and divided into dozens of gangs, many of which clash with each other regularly. Alliances between bandits can be volatile, and compared to jihadis, bandits are quite parochial, clashing over non-ideological issues as minor as one gang stealing cattle from another or erecting its camp too close to that of a rival.28 Consequently, if jihadis were to align closely with one set of bandits, it would likely entail making enemies with a sizable bloc of other bandits or, at best, entail the additional burden of having to constantly mediate between fractious gangs. Additionally, given how frequently gangs break apart, top-down cooptation is no guarantee of the long-term loyalty of a gang: In other words, jihadis might win the loyalty of an individual bandit kingpin, but some of his lieutenants might soon split, depriving the jihadis of foot soldiers they can rely on.

Power of bandits: A second challenge to jihadi cooperation or cooptation of bandits is the benefit to bandits: In sum, jihadis offer little to bandits that they do not already possess. The bandits are more numerous than jihadis,n and the most powerful gangs control large swathes of the countryside. Materially, bandits already receive weaponry from diverse sources, and many gangs are battle-hardened.29 Yet jihadis do appear to offer some benefits: Some bandits seem happy to accept instruction in areas where jihadis have a comparative advantage, such as the use of anti-aircraft guns or IEDs.30 o Similarly, it has been reported that U.S. officials have intercepts of jihadis (suspected to be either ISWAP or JAS) offering bandits advice on staging mass kidnappings and negotiating ransoms.31 But bandits’ need for long-term cooperation with jihadis remains limited; such cooperation may cease as bandits master jihadis’ techniques and no longer need jihadis as teachers. Bandits have outpaced Nigeria’s jihadis in carrying out mass kidnappings, for example, with bandits staging 11 such operations targeting schools since December 2020.p

Different political objectives: A third impediment to jihadis’ cooperation with bandits is that, in contrast to jihadis, bandits are less interested in unifying to overthrow the government than in maximizing their own wealth and influence. Many bandits seek to position themselves for government amnesties, which have historically included financial incentives and legitimated some gangs as state-sanctioned militias.32 This approach stands in stark contrast to jihadis’ deeply ideological projects and the repeated refusal of Nigeria’s jihadis since 2009 to engage in serious negotiations with the government.

Different modus operandi: The fourth and largest impediment to jihadi cooperation with bandits is that the modus operandi of the bandits differs significantly from those of jihadis. Banditry in northern Nigeria requires no substantive ideological justifications and carries no constraints. Bandits rob, kill, and abduct Muslims and Christians; men, women, and children; Hausa, Fulani, and other ethnicities. While some bandits adopt a softer approach of “social banditry” in which they deliver some basic goods and services to the communities they extort, such arrangements are restricted to only those communities that willingly pay levies and accept bandits’ demands.33 Any communities that resist, or those outside a gang’s area of influence that host tempting targets (e.g., a market or school), are fair game. Consequently, the large majority of bandits’ victims in the northwest are Muslim civilians, often those in rural communities who are most neglected by the state.

This is precisely the demographic in which ISWAP and Ansaru seek to build popular support (JAS is a slight exception, to be discussed in the group’s case study). ISWAP attempts to win Muslim “hearts and minds” in the northeast and refrain from harming civilians in the process of collecting revenue.q As the International Crisis Group notes, “[ISWAP] digs wells, polices cattle rustling [emphasis added], provides a modicum of health care and sometimes disciplines its own personnel whom it judges to have unacceptably abused civilians. In the communities it controls, its taxation is generally accepted by civilians.”34 A veteran security official in Borno echoed this, stating to one of the authors that “ISWAP is more dangerous [than JAS] because it treats the villagers well so long as they are Muslim and do not work with the security forces.”35 Ansaru has not yet erected any proto-state, though it similarly tends to avoid harming Muslim civilians and discourages banditry as a means of building popular support.36 In sum, ISWAP and Ansaru have dramatically different approaches toward treatment of Muslim civilians than bandits.

Is Banditry More Appealing Than Jihadism?

If anything, jihadis seem to have had an easier time transitioning into banditry than bandits have had transitioning into jihadism. This seems to be because banditry grants greater autonomy—and greater prospects for accumulating personal wealth—to individual militants than hierarchical jihadi groups that maintain relatively strict (and often unequal) guidelines for dividing war spoils.37 Thus, banditry may be an appealing alternative for militants who grow disaffected with jihad but are unable, or disinterested, in returning to ‘civilian’ life. Indeed, a former commander in JAS and later ISWAP claimed that many jihadis travel to the northwest to become bandits when they fall out with their superiors or grow disillusioned. “They come [to the northwest] with some money and weapons, but once they run out of money, they take up banditry to make ends meet, then become invested in banditry.”38 The journalist Obi Anyadike has likewise reported that out of a group of 21 senior ISWAP defectors, three joined bandit gangs rather than enroll in the government’s amnesty program.39 Separately, one bandit also told two of the authors that in 2018 some JAS fighters arrived in Zamfara who had been sent by Shekau to start operations there. These jihadis drifted into banditry instead because, in the words of the bandit, “there is bountiful wealth in banditry.”40

Scrutinizing Bandits’ Links to Jihadis

With the previous section having laid out just why jihadis have a more difficult time working with bandits, and why jihadis often become bandits but not vice versa, this section offers detailed insights into the nature of bandit-jihadi relations from the perspective of bandits. The authors briefly examine the relations between four of the most powerful bandits operating in the northwest today (Alhaji Shehu Shingi, Halilu Sububu, Turji, and Dogo Gide) and different Nigerian jihadis. These bandits were selected both because the authors have gained reliable information on their activities (drawn in some instances from interviews conducted in 2021 with the bandits in question) and because it has been suggested or speculated, either in Nigerian media or by Nigerian officials, that each of these bandits is working in some way or another with jihadis or has become a jihadi himself. As the authors show, the reality is more nuanced, and in the case of two bandits in particular, Turji and Dogo Gide, behavior or rhetoric that might appear, at a glance, to reflect jihadi leanings might instead require other explanations.

Alhaji Shehu Shingi

Alhaji Shingi embodies a transactional relationship between bandits and jihadis. Shingi has been a bandit in Zamfara since 2011 and identifies his gang as a Fulani self-defense militia.41 In an interview with two of the authors, Shingi denied having any ideological affinity with jihadis but admitted to having intermittent contact with individuals in JAS for several years.42 Shingi stated in August 2021 that he was in touch with JAS lieutenants who were fleeing the northeast amid the ongoing onslaught from ISWAP. Shingi was eager to help these lieutenants reach Zamfara because they would bring significant skills and contacts to his gang.43

Notably, Shingi said that if he did not help these ex-JAS members reach his camps, they might end up in another part of the northwest teaming up with one of his rivals, which he could not allow.44 This points to a commodification of jihadis and ex-jihadis in the northwest in which bandits compete for the loyalty of these skilled fighters. Further research should determine to what extent ex-jihadis have taken advantage of their market value by positioning themselves as soldiers of fortune.

Turji and Halilu

Kachalla Turji and Halilu Sububu are the two bandit kingpins in the Shinkafi Local Government of Zamfara and the adjacent local governments of Sabon Birni and Isa in Sokoto. The two have been rivals ever since Turji, Halilu’s protégé, split from his mentor, though they recently began cooperating again.45 As of early 2022, Turji is one of the most powerful and notorious bandits in the northwest.r

Around 2014, Halilu received an emissary from “Boko Haram” who was looking to cement a partnership between his gang and “Boko Haram.”46 Halilu sent the emissary away out of disinterest.47 However, Turji split from Halilu not long after this delegation arrived, and by 2021 (if not earlier), he had received overtures over the phone from ISWAP, which was looking to cement some form of cooperation.48 Beginning in 2021, Turji implemented elements of sharia law in villages under his control, including mandatory prayer times and a narcotics ban,49 which some Nigerian officials have suggested could be an indicator of ISWAP’s guidance being implemented.50

However, these assumptions seem to be erroneous. A bandit close to Turji denied any ISWAP presence where Turji operates.51 In an interview, Turji himself strongly denied having any relationship with jihadis and denied any presence of “Boko Haram” in his area, saying of his gang, “we are not a religious movement.”52 More notably, in the interview Turji demonstrated little knowledge of Islam or political happenings outside of the northwest, which suggests his worldview has not been seriously shaped by jihadi contacts.53 Some of Turji’s lieutenants said that in 2021, Turji participated in celebrations for mawlud (the Prophet Mohammad’s birthday), a holiday that salafi-jihadis deem haram.54 A former bandit close to Turji also claims it was not ISWAP but a visit by the prominent salafi cleric Sheikh Ahmad Abubakar Gumi, who has made several trips to the bush to hear bandits’ grievances, that had the greatest impact on Turji.55 Gumi appears to have a missionary purpose as he believes that having bandits submit to sharia will make them better Muslims and thus lead them out of criminality.56 Gumi subsequently seconded clerics to the bandits and donated Islamic texts to villagers under Turji’s control.57 Since Gumi’s visit, Turji has gone further than many of his peers in attempting to build legitimacy as a warlord in local communities.58 Employing elements of sharia law (which has been implemented in the north for 20 years, as it was prior to colonialism) can be a useful means of control and may bolster Turji’s image as a community leader. Similarly, Halilu, among other bandits, has built mosques in villages under their control as a form of public works.59

In sum, while jihadism might give bandits a means to morally justify their actions as part of a ‘higher cause,’ it is by no means the only way for a bandit to legitimize themselves. When trying to build influence in a religiously conservative society, a bandit may present himself as a pious community leader but stop short of affiliating with more controversial jihadis. Manifestations of piety from bandits are therefore not the clear proof of jihadi leanings that some might assume.

Dogo Gide

Dogo Gide is an important bandit to study in the context of bandit-jihadi relations. He is the bandit most often referred to by Nigerian officials and in Nigerian media as being linked to jihadis,60 and he has indeed sought to present himself as a jihadi at various points. While the authors have found that Gide cooperates with jihadis, particularly Ansaru (described more in the Ansaru case study), he is, in fact, a highly autonomous bandit who shows little understanding of jihadi ideology. This suggests that even one of the bandits who cooperates most closely with jihadis has not been meaningfully coopted by a jihadi organization.

Dogo Gide is an enigmatic figure,s and the authors have heard several versions of how he first came into contact with jihadis. These narratives are worth considering precisely because each is plausible and, if true, would underscore some of the limits of jihadi efforts to coopt bandits, though in different ways.

The first narrative suggests that Gide formally joined “Boko Haram” sometime after becoming involved in banditry and traveled to the northeast around 2014 along with three other bandits—Dogo Yale, Saidu Jandiga, and Sani Buta.61 Sometime in 2015 or 2016, when “Boko Haram” was facing setbacks at the hands of a multinational military force in the northeast, Gide, Jandiga, and Buta grew disenchanted and decided to return to the northwest and resume banditry.t According to this narrative, Gide’s “Boko Haram” superiors agreed to let them leave and even sent them weapons. As “Boko Haram” splintered, Gide subsequently drifted close to al-Barnawi’s ISWAP even as he resumed banditry in Zamfara, receiving weapons or money from ISWAP.62 If this narrative is accurate, then it is likely that Gide and his associates were part of a group of “Boko Haram” commanders dispatched to the northwest amid military setbacks in the northeast to establish jihadi cells by Shekau’s then-lieutenant, Abu Musab al-Barnawi (who would soon form the breakaway ISWAP faction and maintain contact with these commanders-turned-bandits all the while). (More details on this plan of al-Barnawi’s are provided in the section on ISWAP).

However, other sources place Gide’s first contact with jihadis more recently, particularly after his killing of one-time associate and Zamfara bandit kingpin Buharin Daji (often referred to just as Buharin) in March 2018. In this telling, Gide never joined “Boko Haram” in the northeast but instead began seeking alliances with jihadis, particularly Ansaru, out of pragmatism-cum-desperation after falling out with the late Buhari’s lieutenants.u A similar story suggests that Gide began hosting Ansaru while he was still a lieutenant of Buhari’s, which was a source of friction that may have helped fuel their rift, and that Gide grew closer to ISWAP out of pragmatism after killing Buhari even as he continued cooperation with Ansaru.v In a leaked private communication from 2020, Gide offers a similarly pragmatic explanation for his cooperation with “terror groups” (presumably Ansaru), claiming that by allowing their presence in his area of operations, he keeps the military distracted from pursuing his own gang.63

In sum, the second narrative would suggest that Gide is a pure opportunist with only relatively recent, transactional ties to jihadis. This would support the thesis that bandits are not interested in adopting a jihadi modus operandi. The first narrative, meanwhile, would suggest that Gide has jihadi connections stretching back years and that he may have even originally returned to the northwest as part of a “Boko Haram” plan to recruit supporters among Fulani (described subsequently in the ISWAP section). If this narrative is true, it would reveal a different limitation of bandit cooptation of jihadis: that even a bandit who formally joins a jihadi organization and travels to fight under the command of said organization might quickly return to being an autonomous bandit when conditions change.

This is because, at present, Gide pursues his own interest and does not appear to take orders from anyone. His occasional attempts to portray himself as a well-connected jihadi are not convincing and are likely intended to give him greater prestige and legitimacy as an ‘international’ militant. For example, in a video filmed after masterminding the kidnapping of 90 schoolchildren from Kebbi state in July 2021, Gide begins with the bismillah, then mentions the “khalifah” in an apparent nod to the Islamic State.64 However, in one private communication after the kidnapping, Gide boasted of being a “commander of [Abu Bakr al-]Baghdadi,” seemingly unaware that the Islamic State leader had been dead for nearly two years.65 w In other communications with intermediaries, Gide makes no mention of any jihadi motivation for the Kebbi operation, which he claims was retaliation for the arrest of some of his associates.66 Gide also says that he exclusively kidnaps foreigners (which is untrue) because it is Islamically acceptable to “take from white men,” which suggests a crude knowledge of jihadi theories of ghanima and fey’u (war spoils and confiscations).67 Gide also seems to lack basic Arabic literacy: In late 2021, he circulated a photograph to other bandits of some of his gang’s hostages with a nonsensical Arabic caption that is likely a gross misspelling of the JAS name.68 All of this suggests that if Gide did indeed fight with “Boko Haram” in the northeast in the mid-2010s, he did not seriously imbibe the group’s teachings and has not maintained sufficient contact with jihadis since then to know who is who in today’s global jihadi landscape.

More pertinently, Gide may hold out the possibility of cooperating with jihadis as leverage. After receiving a visit from Sheikh Gumi, the salafi cleric, Gide informed Gumi that Ansaru had warned him against speaking to “pro-democracy” clerics in the future.69 Gide suggested that unless Gumi could convince the government to agree to his demands, he would have to heed Ansaru’s advice.70 Whether or not this is his primary intention in working with jihadis, and regardless of whenever he first made contact with jihadis, it seems that Gide believes his flirtations will help him raise the stakes in any negotiations with the government.

The Limits of Jihadi Cooptation of Bandits

As noted in a previous section, bandits might theoretically seek greater partnerships with jihadis and even find appeal in the ideological dimensions of jihad as a justification for their militancy. In practice, however, this has not been the case. Alhaji Shingi’s experience suggests that bandits are more successful in coopting veteran jihadis than jihadis are in recruiting bandits to their cause. The case of Turji shows that bandits may implement elements of sharia as a means of legitimating their authority but stop short of adopting a full jihadi modus operandi. And the most powerful bandit who can be said to have concrete ties to jihadis, Dogo Gide, does not operate like much of a jihadi himself, even if he may have, for a time, been a subordinate member of “Boko Haram.” In sum, the experiences of the bandits the authors have profiled add weight to the argument that jihadis have largely failed in durably coopting bandits.

The following section shifts the focus to the perspectives of the three primary jihadi factions in Nigeria, showing how their various designs to cooperate with and/or coopt bandits have largely fallen short, though this has not stopped some jihadis from coexisting alongside bandits in recent years.

Jihadi Efforts to Cooperate with and Coopt Bandits—Case Studies

JAS: Inconsistent Cooperation with Bandits

JAS, which emerged as a distinct faction in 2015-2016 amid the split with ISWAP and was led by Abubakar Shekau until his death in May 2021, has enjoyed tactical cooperation with some bandits, and its commanders have historically moved with ease throughout the northwest; but the available evidence suggests that it has not developed durable or ideologically driven partnerships with any bandits. Theoretically, JAS’ modus operandi should be the most accommodating of bandits, but it has, in fact, taken an inconsistent approach toward accepting bandits into its fold, as the authors demonstrate through their examination below of JAS’ fraught ties to the bandit who orchestrated a mass kidnapping in Kankara, Katsina state in December 2020. And though there are allegations made by jihadi defectors, outlined below, that JAS has “cells” in the region, the available evidence suggests this descriptor overstates the ties between bandits or Fulani militias and JAS in most of the northwest and north-central regions. The exception, however, is in Shiroro Local Government in Niger state, where JAS has successfully established a base of operations and presently coexists alongside and probably cooperates with local bandit gangs.

JAS ‘Cells’ Across Northwest and North-Central Nigeria?

After six years in which there was no significant indication of a jihadi presence outside the northeast, JAS released two videos in 2020 that made reference to fighters in Zamfara and Niger states, including footage of one fighter who claimed to be in Niger (no such footage of Zamfara was shown).x After ISWAP killed Shekau in May 2021 and began absorbing some of his fighters into its faction, the then-ISWAP leader, Abu Musab al-Barnawi, also mentioned JAS fighters in Niger and Zamfara states in one of his speeches as among those who should “reunite” with ISWAP (which considers itself the rightful successor of the original “Boko Haram”).71

Defectors of both JAS and ISWAP suggest that between the two factions, JAS was the more successful in maintaining what they refer to as “cells” outside the northeast from 2016 onward. A senior ISWAP defector claimed that Shekau had maintained “loyalists” in the Kafanchan area in the southern part of Kaduna state, Shendam in Plateau state (in north-central Nigeria), and Shiroro in Niger state.72 Separately, a JAS defector claimed that around early 2017, Shekau cemented a relationship with powerful Fulani militias in the north-central state of Nasarawa who helped Shekau funnel motorcycles to his stronghold in Sambisa Forest. These militias pledged bay`a (a religious oath of allegiance) to Shekau in a video that the defector claimed to have seen but was never publicly released.y While the JAS defector claimed that “all the [herdsmen’s] attacks in Nasarawa in 2017” were the work of Shekau loyalists, he could not specify the numbers of these herders and he was not aware if JAS still maintained contact.73

These claims are intriguing, but additional evidence to support the notion of a meaningful JAS presence outside the northeast is lacking with the exception of Shiroro in Niger state, discussed below. While Nasarawa and Plateau states have both experienced heightened religious tensions and, relatedly, conflict between Fulani herders and local farmers in recent years, there is little evidence that JAS has had a meaningful hand in this violence.z It is necessary to consider what a JAS “cell” might entail in the context of north-central and northwestern Nigeria, even though this requires a degree of speculation.

One possibility is that Shekau was liberal in his criteria for accepting bay`a and that he employed limited if any control over most of these “cells” outside the northeast. Of the three jihadi groups in Nigeria, JAS has historically operated the most like bandits. It has been far more indiscriminate in its violence against Muslim civilians than either ISWAP or Ansaru74 and has sustained itself through the wanton raiding of Muslim communities.aa Indeed, JAS has likely gained funds by conducting kidnappings in the northwest alongside bandits.75 Per an ex-JAS member interviewed by the researcher Vincent Foucher, Shekau dispatched a Fulani JAS commander named Sadiku to the northwest “a long time ago” to raise money through kidnappings.76 Another senior JAS-turned-ISWAP commander, Adam Bitri, was reportedly involved in kidnappings with bandits in Kaduna, although it is unclear if he engaged in such kidnappings when he was a JAS commander or after he pivoted to ISWAP.ab

A key difference between the modus operandi of the bandits and that of JAS is that the latter justifies these tactics based on an ultra-exclusivist interpretation of takfir (declaring a Muslim apostate) that encompasses virtually any Muslim who chooses not to live under JAS’ ‘caliphate.’ It is possible then that the requirements for a bandit gang to become a JAS “cell” are relatively minimal: Continue with banditry, but simply claim it in the name of religion. Theoretically, bandits could operate independently on a day-to-day basis and only occasionally conduct operations qua jihadis to satisfy the conditions of their partnership with JAS (with any benefits to the bandits that entails).

Consider the case of the Fulani in Nasarawa who allegedly swore baya to Shekau: While such oaths are not taken lightly in jihadi circles, they do not necessarily carry much weight to the uninitiated, including relatively non-ideological (for lack of a better word) herders. If the bandits of the northwest are any indicator, then any pledges of baya should not be seen as absolutely binding from the perspective of the pledger. As part of previous amnesty agreements, many bandits have sworn on the Qur’an that they have repented from banditry,77 only to quickly resume their armed activities.ac It is quite possible then that bandits or Fulani militias have pledged allegiance to Shekau as part of some quid pro quo without meaningfully adopting a jihadi ideology or subordinating themselves to JAS. Such an arrangement would facilitate transactional relations between bandits and JAS, such as the aforementioned smuggling of motorcycles, without entailing a larger strategic or ideological convergence.

However, the theory that JAS would accept any bandit who pledged a meaningless oath is complicated by the authors’ findings regarding the December 2020 abduction of 300 schoolchildren from Kankara in Katsina state. As it was the first school mass kidnapping outside the northeast, suspicion quickly fell on JAS, which gained notoriety through its 2014 kidnapping of the Chibok schoolgirls.78 Two days after the kidnapping, Shekau claimed credit for the operation, which seemed to be bolstered two days thereafter with a video released by JAS showing one of the kidnapped boys saying he had been abducted by Shekau.79

It soon became clear, however, that the abduction was conducted by the gang of the bandit Auwal Daudawa, who released the boys later that December. An official who debriefed the boys said they claimed that none of their abductors had identified themselves as “Boko Haram.”80 For his part, Daudawa later insisted that he acted alone and was unaware of how the video ended up with JAS.81

Daudawa’s claim is implausible and contradicted by a former associate who was an intermediary in the Kankara negotiations. According to this source, Daudawa made overtures to JAS “long before” the Kankara abduction but failed to cement a formal relationship with the jihadis due to the “stealing and rustling that Auwal [Daudawa] and his team were engaged in. “Boko Haram” did not like people stealing and those engaging in vices such as drugs.”82 At one point, Daudawa sent three associates to Borno to discuss an arrangement, but JAS killed them when they were discovered smoking marijuana. Per this source, no alliance materialized, and Daudawa went ahead and kidnapped the Kankara children on his own accord.83

Shortly after the operation, Daudawa filmed the video of the boy claiming he was Shekau’s captive and sent it to JAS. Daudawa’s likely thinking was that he could up the ante in ransom negotiations with the government, while JAS was happy to create the impression it was expanding outside the northeast.84 Regarding Daudawa’s likely logic, one senior government official with knowledge of the negotiations explained, “If you say you are a kidnapper, the government knows so many kidnappers. If you say you are Boko Haram, there is only one Boko Haram … the government is much more disturbed.”85 This approach seems to have worked, resulting in Daudawa receiving a hefty ransom.ad

It appears then that JAS’ stance on banditry has been inconsistent, possibly as a result of Shekau’s well-documented mercuriality.86 On the one hand, JAS has been more than happy to engage in banditry, both the de facto banditry of its raiding in the northeast as well as its indirect role in kidnapping for ransom in the northwest by the likes of Sadiku. Such tolerance for cattle rustling and kidnapping could have conceivably allowed Shekau to claim “cells” across the north that were, in fact, independent gangs that occasionally cooperated with JAS. On the other hand, Shekau was a genuine jihadi, not a mere criminal, and he could selectively enforce puritanical values, even to the detriment of his group’s expansion.

In sum, outside of the northeast it is questionable whether JAS operates “cells” in the true meaning of the word. Nevertheless, as will be outlined below, it appears that JAS cells have migrated from the northeast to the Shiroro Local Government in Niger state, and that a notable cadre of JAS fighters have regrouped there following setbacks in the northeast, although even here the picture remains somewhat unclear.

The Shiroro Cell

There have been two types of migration of JAS fighters, possibly in the low hundreds,ae into the northwest since Shekau’s death at the hands of ISWAP in May 2021. Some have fled the northeast on their own initiative, eschewing ISWAP and its restrictions on raiding in favor of bandits who will welcome the jihadis, as mentioned in the discussion of Alhaji Shingi. As will be outlined below, others, however, are reported to have relocated as part of an organized effort by Shekau’s successor(s) to regroup in the northwest.

JAS has an advantage in this regard. Whereas evidence of JAS cells in much of the northwest, including Zamfara state, is ambiguous,af Shiroro Local Government in Niger state has become a refuge for JAS for roughly two years. Shiroro is one of the larger of the 25 local governments in Niger, comprising 5,558 square kilometers out of the state’s 76,469 square kilometers,87 and JAS is estimated to be present in five of Shiroro’s 15 wards.88

The jihadis first arrived in Shiroro in late 2019 or early 2020.89 ag After months in the bush, the jihadis made their presence widely known in April 2021, when militants stormed several villages, erected a jihadi flag, and burned one church and other buildings before praying in a local mosque.90 ah Niger state’s governor responded by warning that “Boko Haram” was now just two hours from Abuja.91 The indiscriminate nature of the April 2021 jihadi attacks in Shiroro was more in line with a JAS-style assault than the work of Ansaru, which is based in nearby Kuyambana forest, or ISWAP, which is based in the northeast. Several sources, including the aforementioned ISWAP defector and government officials, have also corroborated the theory that it is a JAS rather than Ansaru cell in Shiroro.92 Interestingly, the April 2021 attacks in Shiroro occurred simultaneously with a series of raids by suspected bandits in the neighboring local government, which could indicate a degree of coordination and/or cooperation between the Shiroro JAS cell and local bandits.93

Since September 2021, the jihadis have become emboldened, taking advantage of the withdrawal of security forces in the region.ai The militants act as de facto authorities in over a dozen villages, implementing their strict interpretation of sharia while ordering families to take their children out of government schools and marry off their daughters.94 No JAS or other propaganda has emerged in recent months claiming a presence in Niger state, suggesting that the jihadis either hope to retain some anonymity or presently lack the capacity to produce and disseminate high-quality propaganda.

It is not known how many jihadis are presently in Shiroro, but the cell there reportedly overpowered the gang of the influential bandit Dogo Gide, which would suggest they constitute a significant fighting force.95 The JAS fighters in Shiroro are likely a mix of the initial group that arrived in 2019 or 2020 as well as more recent fighters who have fled the northeast since Shekau’s death.96 aj It is unclear to what extent the jihadis operate under the command of the so-called Bakura faction, the self-annointed successor to Shekau in the northeast, whose strength is presently hard to gauge.ak The Shiroro jihadis are reportedly led by “Mallam Sadiku,”97 likely the aforementioned lieutenant of Shekau involved in kidnappings in the northwest. Relatedly, according to local media, quoting unnamed Nigerian military sources, an estimated 250 fighters loyal to Bakura have left Sambisa and linked up with Sadiku in Rijana forest in Kaduna state, which is not far from Shiroro.al Assuming both these reports are correct, then it seems that Bakura’s JAS has succeeded in establishing a meaningful presence along the internal state borders of Niger and Kaduna under Sadiku’s command in which to potentially regroup following significant setbacks in the northeast.

ISWAP’s Failed Efforts to Recruit Bandits

Although presently the most dominant jihadi faction in the northeast and, by extension, Nigeria, ISWAP historically has struggled to make inroads into the northwest. This is not for lack of trying. Prior to the split between ISWAP and JAS in early 2016, the future ISWAP wali Abu Musab al-Barnawi (son of “Boko Haram” founder Muhammed Yusuf) took the initiative to dispatch commanders to the northwest with the goal of having them recruit bandits and establish jihadi cells, according to the aforementioned ISWAP defector. Per this defector, who was a close associate of Shekau’s before helping form the breakaway faction, al-Barnawi sought to expand into the northwest amid the heavy losses “Boko Haram” had incurred from an offensive in Borno by a multinational military force in 2015-2016.98 According to the defector, al-Barnawi was still a deputy of Shekau at the time he dispatched these commanders, but he maintained contact with them following the ISWAP-JAS split and his ascension to top of ISWAP.99

Once they reached the northwest, these jihadis drifted into banditry and al-Barnawi lost influence over them, according to the senior ISWAP defector. (As noted earlier, Dogo Gide might have been among these “Boko Haram” commanders who turned to banditry after leaving the northeast.100) Some of these jihadis-turned-bandits reportedly sought to pledge baya to al-Barnawi in the aftermath of Shekau’s death in May 2021.101 It is not known if al-Barnawi ever accepted these pledges (if they were ever even given), however, and the lack of any ISWAP propaganda regarding baya raises the possibility that al-Barnawi assessed these individuals—assuming they indeed pledged bay`a—to have been insufficiently committed to jihad. Per the ISWAP defector, who claims to have known some of these jihadis-turned-bandits, the recent pledges to al-Barnawi were a cynical ploy to get money and weapons rather than an expression of ideological affinity. The defector claimed, “[These men] could not even recite al-Fatiha,”102 referring to the first passage of the Qur’an.103

ISWAP faces a challenge in recruiting bandits that JAS theoretically should not: ISWAP must either convince bandits to radically alter their modus operandi to fall in line with its restrictions on raiding Muslim civilians—which essentially prohibits cattle rustling and all other activities associated with banditry—and agree to receive orders from distant Lake Chad; or it must accept the bandits as they are—independent marauders who mostly harm Muslim civilians—and thus dilute its brand as the ‘softer’ jihadi faction focused on winning Muslim ‘hearts and minds.’ It seems likely then that any ISWAP support for bandits is, for the time being, limited to tactical exchanges with individual gangs—perhaps of money, weapons, training, or the sorts of guidance mentioned in a previous section. There does not seem to be any bandit who adheres to the standard rules of engagement and modus operandi of ISWAP, and it would presumably not be in ISWAP’s interest to let a renegade criminal outfit operate under its name.

It is not surprising then that ISWAP, known for its frequent media output, has not released any material relating to activity in the northwest. Only two “ISWAP” attacks have been claimed or alleged in the northwest region. The first was an unconfirmed 2019 attack in Sokoto state along the Nigerien border claimed by Islamic State media, though the claim noted the assault was conducted by fighters based in the neighboring Republic of Niger, suggesting it was an ISWAP-Greater Sahara operation.104 The second was a September 2021 assault on security forces in Sokoto, which the Nigerian Army claimed was conducted by bandits and ISWAP.105 ISWAP made no claim, and one of the bandits involved staunchly denied any jihadi participation, claiming it was “the Fulani boys” and noting that the military would recognize their voices when they call to negotiate ransoms for abducted soldiers.106 (ISWAP, for its part, tends to kill any soldiers it captures rather than ransoming them.)107

Granted, ISWAP seems to have a new leader since credible reports allege that Abu Musab al-Barnawi died sometime around September 2021.108 It is conceivable then that the new ISWAP wali, Mallam Bako,am might adopt a new, laxer approach to bestowing affiliation to bandit gangs than al-Barnawi did. However, this seems unlikely given that ISWAP’s modus operandi in the northeast vis-à-vis its treatment of Muslim civilians, restrictions on raiding, and focus on attacking hard targets has not changed in the months since al-Barnawi’s death.an

A Sanctuary in Niger State?

In addition to the aforementioned alleged attacks by ISWAP in the northwest in 2019 and 2021, officials in Niger state claim that ISWAP has established a base in the western part of the state around Kainji National Park near the Benin border.109 Officials have offered few details, however, other than that these militants were responsible for the kidnapping of a local traditional ruler in September 2021.ao One source told one of the authors that terrorists (the faction of which he could not identify) have taken over government facilities in the game reserve after troops withdrew from the area in October 2021.110 It is possible that the militants are members of ISWAP-Greater Sahara, which, as of 2019, was reportedly trying to open up a transit area to northwestern Nigeria through Benin;111 ap or they may be other jihadis, such as JAS members who have yet to link up with the Shiroro cell and whom locals have mistaken for ISWAP.

While it is unclear whether ISWAP has a cell in Kainji, the group may see success in Niger state if it can woo the JAS fighters in Shiroro into its fold as al-Barnawi attempted in a speech following Shekau’s death.112 Given Niger state’s large size and limited presence of security forces,aq as well as the fact that the bandits’ presence is mostly limited to the state’s northern border,113 it may be an attractive area for jihadis looking to quietly establish a base of operations.

Ansaru: An Uneasy Coexistence with Bandits in the Northwest

Jama’at Ansar al-Muslimin fi Bilad al-Sudan (“Vanguard for the Protection of Muslims in Black Africa”), better known as Ansaru, formed as a more internationally oriented splinter of “Boko Haram” in 2012. The group has been the subject of much debate among analysts regarding its ties to al-Qa`ida, its relations with the rest of “Boko Haram,” and its operational status (though these doubts about Ansaru’s status have largely vanished since late 2021 with the resumption of Ansaru media operations).ar

The authors’ research shows there is indeed a jihadi group based in Kaduna that calls itself Ansaru, claims to have split from “Boko Haram,” and preaches globally oriented al-Qa`ida-like sermons. Unfortunately, due to the group’s reclusive nature, it is difficult to discern Ansaru’s leadership and, by extension, the degree of continuity between the original Ansaru faction of 2012 and today’s Kaduna state-based insurgents. The Kaduna-based Ansaru has been resilient but also struggled to reconcile its ideological commitment to defending vulnerable Muslim communities from banditry with the exigencies of operating in a bandit-dominated northwest. As demonstrated below in the case study of the “Lakurawa,” a jihadi group that likely contained members of Ansaru and JNIM, Ansaru has had to oscillate between fighting on behalf of bandits and on behalf of their victims. It seems then that Ansaru could be difficult to uproot from the northwest but that it faces more challenges in expanding than many analysts have assumed.

Ansaru in Kaduna

Ansaru announced its formation as a splinter of “Boko Haram” in January 2012 but did not consistently release media thereafter. Per the United Nations, the group “shares ideological similarities with the Organization of Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) … and maintains operational connections with AQIM, including training and attack planning.”114 The group’s early membership reportedly consisted of Hausa and Fulani from across northern Nigeria as well as preachers from Kogi state in central Nigeria115 as who were frustrated with Shekau’s excessive application of takfir and seemingly parochial focus on the northeast. Ansaru made headlines for kidnapping several foreigners in northern Nigeria between 2012 and 2013,116 a tactic that may show the imprint of AQIM. Rather than waging a rural insurgency, the group operated through an urban cell system, notably in Kano and Kaduna, until it was rolled up by security forces in 2014.117

Ansaru “reactivated” in October 2019, per the United Nations, and claimed an attack on a traditional ruler’s caravan in Kaduna in January 2020 through an al-Qa`ida-linked social media channel.118 Following this attack, Nigerian security forces claimed to have conducted military operations against the group in Birnin Gwari,119 confirming local rumors that this local government in Kaduna is Ansaru’s new base of operations.

The group that is presently based in Birnin Gwari may have a somewhat more complicated origin story than the Ansaru of 2012, however, one that suggests that the group has coexisted with bandits in the northwest—albeit with more than an occasional confrontation—for more than half a decade. The insurgents are reclusive, but local residents agree their leader is one “Mallam Abba,” though this could be a nom de guerre assumed by successive commanders.at Residents say the group arrived in Birnin Gwari around 2015 and the fighters came from the northeast.120 Given the timing of their arrival amid the multinational offensive against “Boko Haram,” this could suggest that they were part of a cohort of “Boko Haram” fighters sent by Shekau and/or al-Barnawi to establish cells outside Borno. This theory is bolstered by the fact that the JAS defector interviewed by Foucher claimed that the JAS commander Sadiku whom Shekau sent to the northwest was initially welcomed by another commander named Abba.121 This could indicate that the critical mass of today’s “Ansaru” was actually formed by “Boko Haram” members who split from Shekau after repositioning from the northeast in 2015-2016 and linked up with and/or assumed the mantle of the old dissident faction. This remains only a theory, however.au (For its part, Ansaru reiterated in a recent statement that it was founded in 2012 as a splinter of “Boko Haram.”122)

The jihadis began preaching in local villages not long after their arrival in Birnin Gwari and identified themselves early on as members of “Boko Haram” who had left the group over Shekau’s transgressions against Muslims.123 Ansaru has preached in local mosques, delivering sermons against the Nigerian government, which it says oppresses Muslims, and democracy.124 Ansaru’s preaching is also heavily anti-American in focus, in keeping with an al-Qa`ida-like ‘global’ view. One villager who attended Ansaru sermons said, “They blame problems on America; after the preaching ends, they close with a chant saying may Allah punish America.”125 av

One interesting discrepancy between the original Ansaru and today’s group in Kaduna is that while Ansaru originally claimed the defense of Muslim civilians from Nigerian Christians (particularly in the Middle Belt)aw as part of its raison d’etre,126 the Ansaru in Kaduna does not seem to preach against Nigerian Christians or attack them.ax This is in spite of the fact that southern Kaduna is a longstanding hotspot of religious riots and intercommunal clashes, meaning such messaging could presumably resonate with at least some Muslim communities.

Ansaru’s relationship with bandits—and by extension, its relations with Hausa and Fulani communities (the latter constituting the largest portion of the bandits and the former primarily raising anti-bandit/anti-Fulani militias)—has been complicated. On the one hand, locals believe that Dogo Gide was the first to welcome Ansaru into the Birnin Gwari forests and that his uncle, a now-repentant bandit named Baushi, hosted the jihadis on his land.127 As noted earlier, a former bandit said that Gide had hosted Ansaru in Birnin Gwari for at least three years, overriding the objections of the then-top bandit in the area, the late Buharin Daji.128 Gide has cooperated with Ansaru by, for example, jointly erecting a cell phone booster mast in 2019 in the Kuyambana forest that stretches across Zamfara, Niger, and Kaduna states.129 Ansaru also lent fighters to Gide’s gang in an aborted assault against Gide’s rival, Turji.ay Ansaru has also attempted to woo bandits by selling them weapons (reportedly acquired through JNIM) at below-market rates.130 In addition, Ansaru released a rare public statement in 2019 in Fulfulde (the Fulani language) urging Fulani to join its movement.131

On the other hand, Ansaru has consistently been critical of banditry,132 and its relationship with Dogo Gide has even been tense at times.az While Ansaru has tried to convince bandits to repent and join its jihad, only three small-time bandits are known to have fully joined the group.133 ba Ansaru has instead sought to present itself as a source of protection against bandits and a defender of vulnerable Muslim civilians more broadly.bb This has the effect of pushing Ansaru to align more closely with Hausa communities against Fulani herders, since banditry has resulted in Hausa militias increasing their ethnic profiling of Fulani (the ethnic group from which most bandits hail) and killing innocent herders as retaliation for bandit attacks. Ansaru members have sometimes spread explicitly anti-Fulani messages in the villages.134

Ansaru has clashed with bandits on several occasions, including with Dogo Gide and the powerful gangs of Ali Kawaje (aka Ali Kachalla) and Isa Boka, among others.135 In October 2021, clashes erupted near the village of Damari in Birnin Gwari after Ansaru issued a decree restricting bandits from abducting travelers, which local gangs ignored.136 Ansaru seems to recognize that it cannot be in perpetual conflict with the bandits if it hopes to retain its sanctuary in Birnin Gwari. According to local sources, a tense balance of power exists in the area and Dogo Gide often intercedes when Ansaru has a dispute with local bandits, convincing the jihadis not to attack the bandits in order to maintain peace.137 That Ansaru often heeds Gide’s calls for restraint (though clearly not in every instance) suggests the jihadis recognize they are not presently the dominant force. The bandits of Birnin Gwari, for their part, are said to be intimidated by Ansaru’s ideological rigidity and highly secretive nature while many local community leaders are suspicious of both the bandits and Ansaru.138 As one Birnin Gwari resident told two of the authors, community leaders fear that even if Ansaru were to end banditry in Birnin Gwari, the cure could be worse than the disease: “If these Ansaru finish with bandits,” he said, “what will they do? Look at what happened in the northeast.”139

Al-Qa`ida in Sokoto? Examining Lakurawa

The brief emergence of jihadis near the Nigerien border in Sokoto in 2018 helps highlight some of the challenges jihadi groups face in balancing their desire to be seen as a protector of Muslim civilians with the exigencies of operating within an ethnically divided region dominated by criminals.

Around October 2018, approximately 200 jihadis arrived in Gudu and Tangaza Local Governments in Sokoto from across the border in Niger.140 According to eyewitnesses, the militants rejected the “Boko Haram” label and alternatively referred to themselves as mujahideen, al-Qa`ida, or Ansaru, and spoke of connections to AQIM.141 Other eyewitnesses said the militants were a mix of Nigerians and foreigners, including “light-skinned” or “Arab” fighters believed to be from Mali. Locals referred to the militants as Lakurawa, which could be a Hausa-ization of the French word for “the recruits” (les recrues).142 Based on the descriptions of the fighters, the authors assess that the militants were likely a mix of JNIM and Ansaru members.

The militants patronized local markets, preached in public squares, intimidated clerics, and flogged villagers for playing music or dancing.143 The militants followed informal, roving Fulani settlements (ruga), forcing the herders to pay levies on their cattle under the guise of zakat (religiously obligatory almsgiving) and chastising them for “un-Islamic” activities.144 The militants conducted several attacks on local security forces, ransacking at least one military base. This prompted the Nigerian and Nigerien militaries to conduct a joint offensive toward the end of 2018.145 However, locals report that they still saw Lakurawa members in the area after the military operations but that the jihadis refrained from conducting any attacks.146 All this time, the presence of jihadis in Sokoto only generated a few media reports, which officials quickly denied.147

Local sources say that Lakurawa first arrived in the Gudu and Tangaza Local Governments at the request of the Tangaza district head and local traditional rulers.148 At the time, Tangaza and Gudu were suffering from an influx of bandits fleeing military operations in Zamfara, which led community leaders to seek protection from Niger-based jihadis who promised to fight the bandits and impose order.149 This likely explains the militants’ harassment of Fulani herders, who have become popularly associated with banditry. This approach backfired, however: The herders acquired weapons to resist Lakurawa’s efforts to raise levies on cattle, with some herders, now armed, subsequently turning to banditry.150 Locals also say that Lakurawa’s attempts at ‘Islamizing’ villages were unpopular and that even the community leaders who first invited the jihadis soon sought to expel them. A dispute also erupted over an inheritance that resulted in Lakurawa killing the district head.151

Most interestingly, Lakurawa reemerged in Sokoto in September 2021 amid increased conflict between bandits and the vigilante groups known as Yan Sakai. This time, however, the jihadis have been called in by the bandits and local Fulani communities in an effort to defeat newly raised Yan Sakai militias that have been increasingly attacking Fulani herders.152

The Lakurawa offer a fascinating example in which jihadis fail to form genuine affinities with the communities they swear to protect and instead become something like soldiers of fortune. However, the fact that Lakurawa failed in building genuine popular support is no guarantee that Ansaru or JNIM will never succeed in expanding within northwestern Nigeria. Indeed, Tangaza community leaders worry that some of the radical ideas Lakurawa preached have taken hold among segments of the youth, portending trouble down the road.153

But the experience of Lakurawa does underscore how jihadi expansion is not a straight-forward process. Consider the question of ethnicity: Fulani have been stigmatized as jihadis and radicals across West Africa in recent years, in part due to jihadis’ successful recruitment of Fulani in Mali and Burkina Faso.bc But as seen in the cases of Lakurawa and Ansaru, Fulani communities are just as likely to fight jihadism as they are to embrace it, and the intercommunal dynamics that exist in Sahelian countries are not necessarily analogous to those in Nigeria. Additionally, Lakurawa’s trajectory, like Ansaru’s, underscores that jihadis do not necessarily have any permanent allies or enemies. Reputational considerations and genuine religious conviction may mean that jihadis prefer to act as the defender of Muslim communities against criminals, but the exigencies of war can make partnering with criminals more attractive.

Conclusion

The security situation in northwestern Nigeria is highly volatile and unpredictable. The presence of jihadis in the northwest and the instances of tactical cooperation between bandits and jihadis the authors have documented constitute an unfortunate dynamic in an already complex region. For this reason, the jihadi presence in the northwest requires further study and continued monitoring.

However, jihadism remains a minor dimension within the overall conflict in the northwest, and the authors predict this will continue to be the case for the foreseeable future for the reasons explained throughout this article. Most notably, the bandits are very powerful and have little to gain—and much to lose—by subordinating themselves to a jihadi organization and its rules. The bandits’ fractiousness also leads the authors to doubt that any significant portion will rally under one flag for a sustained period of time. If the bandits begin to reconsolidate under a smaller set of kingpins (as was the case in the early 2010s)154 and adopt more coherent political objectives, then avenues for a serious partnership with jihadis may grow. But despite some increased inter-gang cooperation in response to recent military pressure,155 it is unlikely that the fractured and criminal nature of the bandits’ insurgency will fundamentally change anytime soon.

With this in mind, analysts and stakeholders should beware overhyping the jihadi angle in the northwest, as this could have significant policy implications. Many of the standard counterterrorism and preventing/countering violent extremism (P/CVE) approaches developed over the past 20 years of the “War on Terror” are unlikely to have much effect against bandits. Leadership decapitation, a tactic that has had mixed results against jihadis,156 is unlikely to meaningfully degrade loosely organized militants whose gangs already undergo high rates of fragmentation.bd While Nigeria has made progress in developing P/CVE approaches for jihadism in the northeast, any such strategic communications and deradicalization programing would need to be significantly retooled for a context in which most militants are not motivated by religious ideas. And in contrast to the jihadi insurgency in the northeast that pits rebels against the state, insecurity in the northwest is rooted to a large extent in conflict between communities in which the state is either absent or complicit. This has significant implications for any DDR (demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration) effort as bandits are unlikely to “repent” en masse unless the militias that fight bandits and Fulani, namely the Yan Sakai, likewise stand down.

In addition to shedding light on Nigeria’s myriad security crises, the authors hope this article will add nuance to analysts’ understanding of the oft-hyped “crime-terror nexus.” As Stig Jarle Hansen has recently argued, analysts must be wary of assuming that criminality and jihadism naturally converge simply because both are “bad.”157 While Hansen argues that jihadis generally remain committed to their ideology and do not converge with criminals to the extent that much of the nexus literature suggests, the authors’ research shows the inverse is also true: Criminals can be a stubborn lot who do not necessarily turn to jihadism simply because they are Muslim and dislike their government. Similarly, the failures of jihadi efforts to expand into northwestern Nigeria are just as worthy of study as jihadi successes. These failures are a reminder that the trajectories of jihadi insurgencies are contingent on unquantifiable and multivariate factors that cannot be reduced to a few buzzwords such as “ungoverned spaces.”

With this in mind, the authors conclude with a call for analysts and policymakers to see the situation in northwestern Nigeria for what is: a massive and complex conflict in its own right, not simply a potential arena for jihadi expansion.