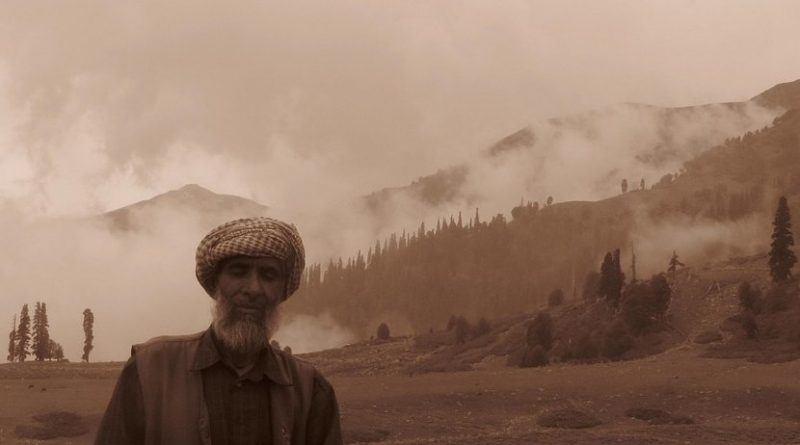

Recent political developments in Jammu and Kashmir have opened a debate that some kind of democratic recovery has started in this conflict-ridden part of India and perhaps even the whole country. Yet a closer look shows that it is too early for such optimism.

On 24 June 2021, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and members of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) government met with local leaders in the region including members of the People’s Alliance for Gupkar Declaration. The objective of the Alliance is to roll back the decisions taken by the BJP government in August 2019, which split the former state into two new Union territories and removed the constitutional autonomy that Jammu and Kashmir had enjoyed before. Since then, local political leaders have faced arrest and freedom of the media has been severely curtailed.

A decision by Modi to talk directly with ‘mainstream parties’ and their leaders in Kashmir could certainly be interpreted as a step towards de-escalating tensions. Modi promised that elections will be held ‘soon’ in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. Unfortunately, there are several reasons not to get hopes up about this being the beginning of a democratic revival in Jammu and Kashmir, or in India in general. The political conditions in the former state reflect the democratic crisis at the national level.

Local leaders agreed soon after the meeting took place that no tangible results had been achieved. If any political leaders in Jammu and Kashmir could have expected a positive outcome from the meeting, it would have been those Gupkar Alliance leaders in attendance, who have been known to work together politically with the BJP – such as Farooq Abdullah and Mehbooba Mufti. Yet even they found the meeting unhelpful. Very few political leaders seem to think effective democratic elections can be held anytime soon. So why did Modi even bother holding the meeting?

One common explanation is that Modi wanted to give the impression that India is ‘normalising’. He may have wanted to counter severe international criticism aimed at him and his party for pushing the country into authoritarianism. The lack of clear and effective strategies for handling the country’s COVID-19 crisis and its underperforming economy have also recently undermined public support for the Modi government. The visit may have been an attempt to divert media attention to something positive.

There may also have been some idea of expanding the number of seats in the Jammu and Kashmir assembly. This is in accordance with reforms proposed by the Jammu and Kashmir Delimitation Commission, which critics label as BJP-orchestrated gerrymandering. Perhaps the anticlimactic results of the meeting reflect the fact that, when it comes to difficult political issues, Modi and his government have no thought-through solutions to offer.

There is currently nothing to indicate that the meeting in Jammu and Kashmir reflected any increased interest in democracy on Modi’s part. The prevailing direction, both in Jammu and Kashmir and in India in general, suggests the opposite. In Jammu and Kashmir, discontent is so severe that militancy has once again increased. As for India under Modi’s command, it is showing no signs of wanting to reverse the ongoing autocratisation.

Autocratisation in India cannot be blamed solely on the BJP. The Congress Party, for example, undoubtedly mismanaged India’s democracy during its previous term in power (2009–2014). Yet it is clear that Modi is pursuing a deliberate strategy to dismantle democracy in a different way to anything of which the Congress governments of 2004–2014 can be accused.

In India today, autocratisation has gone so far that journalists and human-rights activists are being imprisoned without fair trial. To take one important recent example, Stan Swamy, an 84-year-old Jesuit priest who was incarcerated in 2020 with others accused in the ‘Bhima Koregaon’ case — and who was already severely ill when arrested — died while waiting for his bail hearing at the High Court of Bombay.

If there is no break with the current trajectory, within a couple of years India may be even less democratic than it was during the mid-1970s. It also seems that India’s neighbours have little interest in democracy. In particular, China provides incentives for the whole region to shun democratic ideals as denoting weakness of character.

There is little to support the notion that the meeting in Jammu and Kashmir represented anything like a democratic turn in that region. Instead, and once again, Jammu and Kashmir are at the epicentre of something completely different.