With more than 4.2 million euros-worth of NATO contracts between 2020 and 2022, Glotec is a poster boy for the economic benefits of accession to the Western military alliance.

Based in Montenegro, the supplier of aircraft and engine spare parts and wind tunnel testing kits has made the most of the business opportunities the country’s leaders touted when Montenegro joined NATO in 2017.

Besides the obvious security benefits, Montenegro and North Macedonia both framed accession as a matter of economic opportunity, throwing open the doors to a market valued at over 10 billion euros and boosting the countries’ appeal to foreign investors.

In reality, the gains have been modest, at least according to publicly available information.

Glotec, which did not respond to a request for comment, is one of just four Montenegrin firms currently entitled to bid for contracts with NATO’s main procurement and logistics support agency, the Support and Procurement Agency, NSPA, in Luxembourg.

With 48 firms completing the registration process, North Macedonia appears to be faring better, but only one is listed in the NSPA database as winning any contracts between 2020 and 2024, worth 2.6 million euros. That compares, for example, with 48 million euros of NATO business secured by firms in neighbouring Bulgaria – which is only roughly three times bigger in terms of population – in 2023 alone.

Experts say authorities in both countries have been slow to help their respective industries, and question whether the business sectors involved have the capacity to take advantage of the opportunities unleashed by accession.

“NSPA contracts require rigorous adherence to NATO standards, which can be challenging for many companies in North Macedonia,” said Dr. Metodi Hadzi-Janev, a professor at the Military Academy in Skopje and former brigadier-general. “Historically, there has been limited structured support from Macedonian institutions to help local businesses prepare for NATO procurement opportunities.”

“The absence of targeted training, advisory services, and resources have made it difficult for local firms to navigate the complex NSPA bidding process, contributing to their low participation in NATO tenders.”

With populations of 620,000 and 2.1 million respectively, Montenegro and North Macedonia – both former Yugoslav republics – are far from the biggest or strongest members of NATO.

Montenegro has just 2,350 active-duty soldiers, but in joining NATO in 2017 it gave the alliance full control over the Adriatic Sea; North Macedonia, which became a member in 2020, has around 10,000 active military personnel and sits to the south of Kosovo, where NATO has had a peacekeeping force for the past 26 years.

Accession opened up access to NATO tenders for a plethora of goods and services, from construction to catering, transport to healthcare. More than 20,000 businesses across the alliance are registered as trusted suppliers, but their peers in North Macedonia and Montenegro have struggled to gain a foothold.

The NSPA database lists only three contracts awarded to a single Macedonian company between 2020 and 2024; only four Montenegrin firms, including Glotec, have qualified to bid.

It was only in 2023, six years after accession, that the Montenegrin government took any significant steps to streamline the administrative procedures and eligibility criteria for participation in NATO procurement.

The government at the time entrusted the Montenegrin Chamber of Commerce with overseeing the registration process.

“Registration is one of the mandatory requirements for the further qualification process of NATO procurement participation,” said Eleonora Albijanic, spokeswoman at the Montenegrin Chamber of Commerce. The first firm was registered in August 2023; since then, a further three have joined and Albijanic said approval was pending for “several others”.

One of the registered companies holds a security permit from Montenegro’s Directorate for the Protection of Classified Information, allowing it to participate in NATO tenders at the highest classification levels; another is in the process of securing the permit, the Directorate told BIRN.

The NSPA only publishes the details of contracts worth more than 80,000 euros.

In 2017, for example, the Montenegrin explosives manufacturer Poliex Berane won a tender worth nearly 135,000 euros.

In the case of North Macedonia, in 2021 the defence ministry established a business support centre to help companies prepare for NATO tenders, with the defence minister at the time, Slavjanka Petrovska, touting their competitive advantages “in the food, textile and metal industries”; the following year, the country’s Chamber of Commerce launched a ‘NATO and the Business Community’ subcommittee to help match businesses with tenders.

As of spring 2024, 48 firms had completed the registration process in North Macedonia, the defence ministry told BIRN. The process requires submitting 18 different documents, including a balance sheet and list of buyers for the past three years.

According to the Chamber of Commerce, registration should take no more than 30 days, after which a company can track NATO tenders as they are published.

Complicating matters, however, is the fact that North Macedonia has yet to post a defence ministry representative to the NSPA’s HQ in Luxembourg, a process that stalled with the change of government in 2024.

Slavjanska Petrovska, who served as North Macedonia’s defence minister between 2022 and 2024, said such a representative would liaise with the defence ministry’s business support centre and the Chamber of Commerce.

Giving the example of the textile industry in eastern North Macedonia, Petrovska suggested a consortium of textile companies could be created to submit joint bids for NATO tenders.

The one Macedonian-registered company to win any contracts with NATO so far is actually the Macedonian branch of a well-known Kosovo-based construction company called Eskavatori.

Hadzi-Janev said the state should provide more structured support, including targeted training and clearer procurement guidelines to help businesses better navigate NATO’s complex procurement procedures.

Corruption risks

In both North Macedonia and Montenegro, the shadow of deep-rooted corruption looms large over any public tender process.

Security analyst Milan Stefanovski said the risk of corruption in NATO tenders is “very small” but that decades of graft and political nepotism contributed to lingering fears.

However, Hadzi-Janev, of the Military Academy, said that the process of gaining access to NATO tenders may prove fertile ground for “political influence, favouritism, and bureaucratic manipulation”.

“Politically connected firms may sometimes be favoured, especially when governments change frequently and bring shifts in alliances and interests,” he said.

No discernible impact on FDI

Besides providing access to the NATO procurement market, accession to the alliance has also been touted as an additional stimulus for foreign investment. According to that rationale, membership speaks to a country’s security, stability and commitment to reform, all of which should be reassuring to foreign investors.

A comparative snapshot of Bulgaria’s FDI before and after the country joined NATO in 2004, shows that FDI shot up from 7 per cent of GDP in 2000 to 18.90 per cent in 2008, a fact North Macedonia’s finance minister in 2018, Dragan Tevdovski, pointed to as an incentive to pursue membership. The Baltic states saw similar economic boosts.

Albania ahead

The biggest NSPA contracts awarded to companies in the Balkans have gone to two firms listed in the agency’s database as registered in Albania – oil company EXFIS and construction company EUROING.

Albania joined the alliance in 2009; between 2017 and 2024, 10 Albanian-registered firms secured NATO contracts worth more than two billion euros. The biggest, worth almost two billion, went to EXFIS, which is in fact based in neighbouring Kosovo; EUROING won contracts worth 63.7 million euros.

However, a 2018 report from the European Policy Institute, a Skopje-based think tank, said that such trends cannot be attributed solely to the benefits of NATO accession, since accession in many cases coincided with integration into the European Union and accompanying structural reforms.

In Montenegro, FDI in 2019 – two years after accession – was roughly the same as in 2015 [770 million and 750 million euros respectively]. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 triggered a spike in real estate investment by Russians and Ukrainians, taking total FDI to over one billion euros that year, but it fell back to 880 million in 2024.

Collectively, NATO member states account for a large share of FDI in Montenegro, but no single member stands out; historically, Russia has been the biggest single source of foreign investment in Montenegro since the country gained independence in 2006.

Since NATO accession in 2017, only once – in 2018 – did a NATO member, Italy, take the top spot in terms of FDI. This was likely thanks to a project laying an electricity cable between Montenegro and Italy, which was planned well before Montenegro joined the alliance.

In the case of North Macedonia, global events dampened the impact of its NATO accession, which coincided with the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing economic downturn.

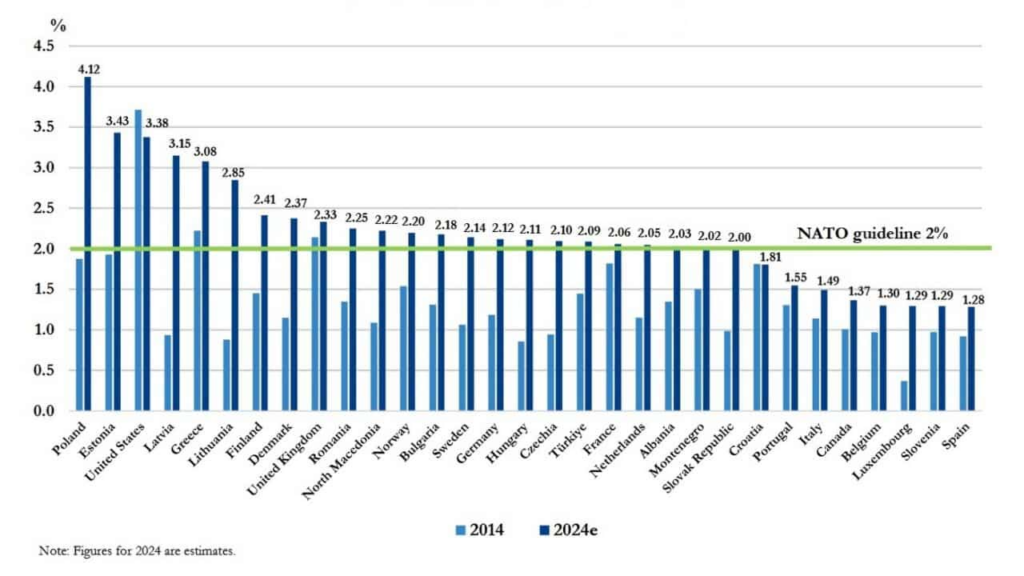

Nevertheless, the war in Ukraine triggered a surge in defence spending by NATO allies – 18 per cent up on 2014.