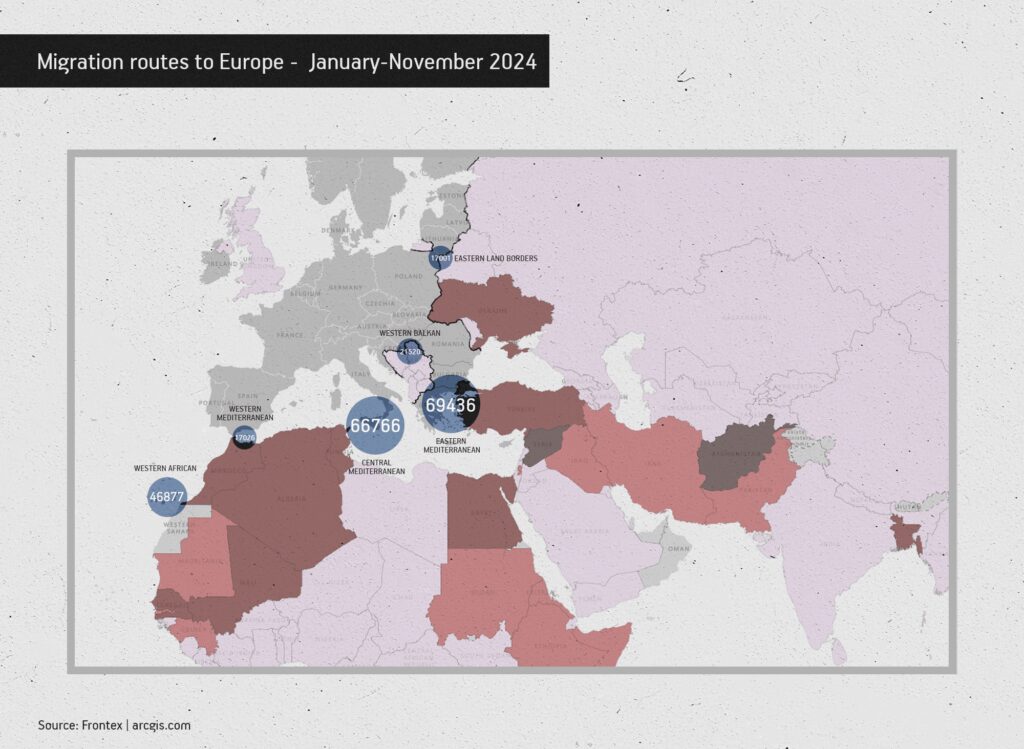

Just over 220,000 migrants were detected trying to cross into Europe illegally in the first 11 months of 2024, according to Frontex data. That represents a decrease of about 40 per cent from 2023, and is several orders of size smaller than the numbers seen in 2015, when around 1 million Syrians made their way to Europe to escape the civil war back home. However, the perilous Western African route saw a record 46,843 people reach the Canary Islands illegally in 2024, up 19 per cent from 2023.

The breakdown per migratory route in January-November 2023 was as follows:

Eastern Land Borders route: 16,530 arrivals

Western Balkan: 20,526

Eastern Mediterranean: 63,935

Central Mediterranean: 62,034

Western Mediterranean: 15,412

Western African: 41,756

- Overview

Even though the total number of migrants detected trying to cross into Europe illegally fell further in 2024, the number of asylum applications remains high and on course to top 1 million again. Since 2020, EU+ countries (EU states plus Norway and Switzerland) have been receiving increased numbers of asylum applications. In 2023, 1.1 million applications were lodged in the EU+, marking an 18 per cent increase from the previous year, and the most for seven years. During the first half of 2024, 513,000 applications were lodged in the EU+, which is more or less comparable to the first half of 2023, when the highest January-June level was recorded since the refugee crisis of 2015. The EU Agency for Asylum (EUAA) notes that more applications are usually lodged in the second half of the year. German news agency DPA and newspaper Welt am Sonntag reported in January that the EUAA’s full-year 2024 figure for asylum applications in the EU+ came in at just over 1 million, down 12 per cent from 1.14 million in 2023.

Given the surge in support for right-wing populist parties across the continent in the June 2024 elections for the European Parliament, European politicians have been scrambling to look tough on migration.

In September, Germany, one of the main recipients of migrants to the EU, announced the introduction of spot controls on all of its borders, following a fatal knife attack by a Syrian asylum seeker who was about to be deported in the Western town of Solingen. At the time, German Interior Minister Nancy Fraser told a press conference the checks would not only limit migration but also “protect against the acute dangers posed by Islamist terrorism and serious crime”.

Such border controls had already been in place with four of Germany’s neighbours – Austria, Poland, Czechia and Switzerland – and were prolonged that month. Additionally, entirely new controls were introduced on Germany’s borders with France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Denmark.

Importantly, the checks were introduced against the backdrop of regional elections, in which the far-right AfD made exceptional gains, winning in the eastern state Thuringia and coming second in Saxony. Migration, of course, was a central topic during the election campaign.

Italy, headed by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni whose Brothers of Italy party has far-right roots, has been another major recipient of migrants and experimented in 2024 with opening hotspots to process asylum applications outside its territory in Albania. Legal challenges have undermined the project. Similar scenarios have been explored by the UK and Germany.

In Central and Eastern Europe too, politicians have either maintained their tough stances on migration (if on the right of the political spectrum) or hardened them (if liberals).

The Hungarian government of Viktor Orban has taken a strict line on immigration since 2015. This year, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) imposed a 200-million-euro fine on Hungary (plus 1 million euros for each day of delays in not implementing the ruling), for its restrictive migration policies, which were determined to make it virtually impossible to apply for asylum while also allowing for pushbacks at the border.

Despite the tough stance on Hungary from the European Commission and the European Court of Justice, the European mainstream has actually been shifting significantly in Orban’s direction over the last few years. So much so that the Hungarian leader felt vindicated enough to proclaim that his old predictions about the non-viability of the EU’s passport-free zone and migration policies were coming true.

“Since 2015, I have been called either an idiot or an evil person for my stance on migration. But, at the end of the day, everyone will agree with me,” Orban told reporters at his international press conference in October in Strasbourg.

Slovakia had already toughened its position on immigration at the end of 2023 when Robert Fico returned to power, governing together with two other parties, one of them the extreme-right Slovak National Party. Soon after Fico came to power, the country stopped being a regional hub of sorts for migrants trying to make their way from the Balkan route or even Belarus into Western Europe.

And in Czechia, the populist ANO party of former premier Andrej Babis looks poised to retake power in the 2025 general election, possibly in league with the far-right SPD, with Babis exploiting the migration issue already for months.

To me and many other professionals working on migration and refugee issues, it’s just a political document and a very populist one at that, full of fear and playing on the fears of people.”

– Marianna Wartecka, Board Member of the Ocalenie Foundation

Perhaps most surprising of all has been that Poland’s new liberal government, led by Donald Tusk, chose to not only continue the anti-migration policies of the previous nationalist-populist Law and Justice (PiS) government, but to actually take them one step further. In fact, Poland under Tusk could become the most hardline country on migration in the whole of Europe in 2025.

In mid-October, Tusk, seen as a centrist politician, announced the suspension of asylum rights due to pressure on its border with Belarus, which is being caused by the regime of President Aleksandr Lukashenko bussing tens of thousands of migrants to its borders with the EU and herding them across to foment a crisis. In mid-December, the government published proposed legislative changes that would allow the executive to suspend asylum rights by decree for a period of 60 days on a specific segment of the border.

If the Polish parliament approves the legislative changes, which is likely, Poland will become the first country in the EU to actually write in law the suspension of the right to asylum, so far considered a fundamental human right. Importantly, pretty much at the same time when the Polish government presented the proposed legislative changes to the public, the European Commission appeared to give its green light for such legal changes. In mid-October, the EU Commission issued a communication in which it indicated that member states can, in such special circumstances as a hybrid war with Russia and Belarus, introduce measures that “may entail serious interferences with fundamental rights such as the right to asylum.”

A further indication of how widespread the anti-migration mood was in 2024 is the call made in October by 17 EU countries demanding a “paradigm shift” in the bloc’s migration policy, a strengthening of the external borders, and a radical toughening of the return procedures for asylum seekers who have had their applications turned down. This is despite EU countries adopting, after years of negotiations, a major overhaul of migration rules dubbed the EU Pact on Migration and Asylum. Migrant and human rights NGOs have condemned the pact already introducing a more restrictive approach to helping migrants and refugees.

The Migration Pact speeds up asylum procedures for some categories of migrants, quickening the deportation of those rejected. It envisages emergency procedures for crisis periods which allow for the prolonged detention of migrants. It also introduces a controversial burden-sharing mechanism, under which migrants can be relocated from countries of arrival to less exposed ones, or the latter can help support the costs of processing applicants.

For some EU governments the new Migration Pact does not go far enough. The pact was rejected by Hungary and Poland – although this does not prevent it from entering into force – while others in Central Europe abstained on it. Babis described the Migration Pact as a “huge betrayal” that would lead to the “insidious disease” of mass illegal migration, “a cancer that is destroying European society”. The October call by the 17 EU countries indicates many others want to go even further in closing the EU’s borders to migrants than the Migration Pact already does.

“We’re already hearing that, during the Danish Presidency, which comes after the Polish one in the first half of 2025, they plan to present even bigger changes to the migration and asylum law in the European Union than the Migration Pact has,” Marianna Wartecka, a board member at Fundacja Ocalenie, one of the main NGOs dealing with migration in Poland, told BIRN in an interview.

“The plan is to give [EU border agency] Frontex more power, including the power to operate officially in third countries as well as to assist in deportations from third countries to other third countries,” Wartecka continued. “Mass deportations will be made easier than they are now, and the externalisation of migration approach will be expanded.”

In the meantime, CEE countries are having to deal with the reality of immigration and how it will transform their societies.

In Poland, migrants from non-European countries entering via the Belarusian border are a small minority of the total migrant population in the country. There were about 30,000 attempted entries and around 2,000 asylum applications accepted on the Belarusian border in 2024, versus 1 million Ukrainian refugees residing in the country.

In October, when Tusk announced the suspension of the right to asylum on the Polish-Belarus border, he also spoke about his government’s efforts to adopt, for the first time, a migration policy for the country – indicating the government is ready to take ownership of the fact that Poland has turned into a destination country for migrants.

Since then, the government has published a 35-page document that sets out the basic principles of a migration strategy. Major organisations working on migration in Poland got to express their views on the document post-factum, during a public hearing on November 25. Most of them lambasted the document for depicting migration primarily as a threat and being scant on details otherwise.

“The language of the document depicts migration as a negative process overall, as a social problem which requires control,” Mikolaj Pawlak, a sociologist specialising in migration from the University of Warsaw, told BIRN. “But I try to take heart in the fact that the document is open and so, starting from the premises outlined in it, everything is possible.”

Pawlak pointed to the person in charge of the policy being Michal Duszczyk, deputy interior minister, who is one of the country’s foremost experts on the issue of migration and, Pawlak believes, “very conscious that migration is not something you can fully control”, despite public claims to the contrary by Tusk and his colleagues.

“My hope is that behind the tough talk that Tusk engages in for electoral reasons, the experts in charge and the various ministries will be implementing measures that are really needed to help with the integration of migrants,” Pawlak said, adding that there were positive signs out there already if one took a closer look at measures adopted by the various government branches.

“You anyway cannot address the problems migrants face in Poland today just via a migration policy,” Pawlak said. “Complex actions across sectors are needed.”

Wartecka from Ocalenie has a different opinion: “Integration is a two-way street,” she argued. “If you make Polish society afraid of migrants, integration won’t work even if you provide institutional instruments for integration like integration centres for foreigners for example.”

“This kind of rhetoric that is the main tone of the strategy, that we should be afraid, actually compromises many efforts towards integration,” Wartecka said.

- Signals to watch in 2025

Implementation of the EU Migration Pact: The new Pact on Migration and Asylum entered into force in June 2024 and should start being implemented after two years, in June 2026. However, as of mid-December 2024, half of the EU countries had failed to submit their National Implementation Plans before the deadline set by the EU Commission, which points to likely delays – if not more serious derailments – in the implementation of the plan. The Polish government has said it has no intention of submitting its National Implementation Plan soon after the deadline and the pact as it stands today is incomplete.

Poland’s legislation on asylum and migration policy: Poland’s parliament will vote in 2025 on the government’s proposal to introduce “temporary and territorial” suspension of the right to asylum into national legislation. If that passes, that will be the furthest a European country has gone so far in moving away from safeguarding refugee rights, by including the possibility of suspending the right to asylum directly in national legislation. Other countries may be emboldened to act in a similar manner.

Changes to Geneva Convention in the works? The Times reported on February 3 that it has seen a diplomatic paper, drafted by Poland and discussed by EU interior ministers at the end of January, which looks to overhaul the 1951 Refugee Convention that prevents countries from rejecting asylum seekers at their borders, enshrined in the fundamental principle of non-refoulement, in what the paper said may be one of the biggest shifts in migration policy in decades. “It should be noted that these principles were developed after the end of the Second World War, and were characterised by a very different geopolitical situation to that of today,” reads the diplomatic paper, The Times reported.

Czech election: Parliamentary elections to take place in Czechia in October 2025 are likely to bring the populist billionaire Andrej Babis back to power, possibly in coalition with some far-right political force. Babis, who is already speaking aggressively against immigration, is likely to toughen the country’s already none-too-soft line on this matter. That will make the entire region determined to maintain a hardline on immigration.

War in Ukraine: While the inauguration of Donald Trump might bring speedy peace negotiations in Ukraine, perhaps to the detriment of Kyiv, it is entirely possible that the war will also continue for another year or more. With Russia systematically attacking civilian infrastructure, especially the energy infrastructure, the civilian population – increasingly weary – might be pushed towards a new wave of emigration if more significant and violent developments ensue. As before, countries in CEE would be the first ports of call for the new refugees.

The language of the document depicts migration as a negative process overall, as a social problem which requires control.”

– Mikolaj Pawlak of the University of Warsaw

Situation in the Middle East: Following the downfall of the Assad regime, Europe is busy counting its Syrian refugees to see how many it can send back and how fast. But ever since Israel’s war in Gaza in retaliation for the Hamas terrorist attack in October 2023, followed by its attack on Hezbollah and southern Lebanon and heightened tensions with Iran, the situation in the Middle East remains fraught. While European countries are doing their best to seal themselves off from new arrivals, the rich continent remains the top destination for those seeking to escape countries in the region if conflict expands.

An expert view

What is your opinion about the 35-page migration strategy document presented by the Polish government?

That document doesn’t have the key elements of a strategy, so it’s hard to call it a strategy. It doesn’t have a schedule of implementation, a methodology for evaluating the implementation, an analysis of the current legal framework on migration, or a list of proposed changes in the legal framework that would be necessary to implement the strategy; there is no data on immigration in Poland in the strategy or even links to resources on such data. So, it’s lacking in too many crucial areas for us to be calling it a strategy really.

To me and many other professionals working on migration and refugee issues, it’s just a political document and a very populist one at that, full of fear and playing on the fears of people. Instead of mapping and addressing some fears of people – which are understandable because migration is a global phenomenon which is out of individual and even singular state control – this strategy is trying to scare people even more. And it’s not only the case with refugees and irregular migration, but with migration in general.

If you read through the strategy, it’s all about crime, misuse of the system, corruption schemes, people getting visas who shouldn’t get them, fake academic institutions, employers who want to cheat the system and hire underpaid people instead of Poles. And, of course, those are all pathologies that happen and should be addressed and prevented, but still this is not the whole picture, while the strategy presents those pathologies as the whole picture. Everybody lies, everybody tries to misuse the system. It’s actually really ironic that the document is called “a comprehensive and responsible migration strategy”, because it’s not comprehensive, it focuses on some singular aspects, and it’s not responsible, but the opposite of that.

Is there a chance this government talks tough, but behind the scenes will take a more constructive approach to integrating migrants?

Integration is a two-way street. If you make Polish society afraid of migrants, integration won’t work even if you provide institutional instruments for integration, like integration centres for foreigners for example. It’s a good thing such centres are being established (10 years too late, but good to see them), good that migrants will have places specifically designed for them to help them with day-to-day challenges and different integration processes. Still, integration and inclusion are not possible without Polish society being active in this process. So, we cannot make people afraid of migrants and at the same time expect migrants to integrate and feel welcome and included in Polish society. In my opinion, it’s impossible to do those two things simultaneously. This kind of rhetoric that is the main tone of the strategy, that we should be afraid, actually compromises many efforts towards integration.

Will the government actually suspend the right to asylum or is this more political talk?

They actually published draft amendments to the national legislation on granting foreigners international protection in Poland two days ago. It’s exactly what they declared was going to happen, those are legal revisions to introduce the possibility of a “territorial and temporary” suspension of the right to seek asylum. What they proposed now is exactly what they declared back in October and it’s contrary to the Polish constitution, the Geneva Convention, European Union law, the European Convention on Human Rights, and against Polish and European court rulings.

If it passes, it will be the biggest breach of human rights in contemporary Polish history that is so explicit in the legal system, not just “common practice”, but a breach of human rights actually explicitly included in acts of law. And it will pass, because they have a majority in the parliament and they want to do it.

Normally we should have an activisation of the Constitutional Court in this case, if the proposed changes are contrary to the Polish constitution, but I understand you do not expect this to happen?

No, no, of course it won’t happen. This is actually a very sad but very predictable outcome of the fact that the previous government destroyed the independence of the Constitutional Tribunal. So, the current government – even though they declare that they want to bring back the rule of law – is actually using this destruction of the rule of law, of the checks and balances mechanism, to pass all those revisions and amendments that are basically against the Constitution and international law.

Let’s look at the European context and international one. When announcing the measures, Tusk said Finland was doing the same already, plus pushbacks happen on other European borders. Is Tusk pushing the toughening of European policies on migration one step further, or is this just European business as usual?

Actually, even if the Finnish solution is quite bad, it’s far from what Poland wants to do, because Finland has mechanisms for migrants to apply for international protection in Finnish embassies and consulates around the world and this is not the case for Poland. For that reason alone, in the Polish case, it will become impossible to apply for asylum at all if the government passes such a decree. The solution they want to implement is close to the Hungarian solution, even if Tusk doesn’t want to admit that, it’s what Hungary has been doing for several years and has been actually fined for it by the Court of Justice of the EU. That’s what Poland might also be facing from the EU.

Except that we have a very different political context and the European Commission might not be interested in sanctioning Poland.

Yes, but the Commission is one thing and the Courts are another. Even in this so-called migration strategy published by the Polish government, the text includes an admission that the only obstacle to implement what the government calls “a practical approach to human rights” are the courts, international and national. This is funny because they actually blame the courts for following the law. They said it many times, including Tusk himself, that they are aware that pushbacks are illegal, but they say it’s the thing we have to do now, that it’s necessary.

Q: Tusk did say, when announcing this measure, that the Polish government is going to actively pursue changes in international law when it comes to the right to asylum.

Yes, but this is not going to happen. It will just continue to stay illegal. With all due respect to Poland’s standing on the international arena, Donald Tusk will not change international law. And [Maciej] Duszczyk won’t either. Once Poland becomes the vanguard of the “practical approach to human rights” – whatever that means – other countries might follow the example in practice, but the letter of the international law won’t change.

I’m really amazed by the level of paradox. I really love some quotes of some phrases from the strategy and from what we hear from the Ministry of Interior in the past year, things like “humanitarian pushbacks” or “practical approach to human rights” or humanitarian workers and activists described as “human rights radicals”. It’s a new kind of language. The previous government was using the old propaganda language, the worst kind of it, but this government is creating a new language for it, which is softer but also contradictory and somehow absurd.

Let’s come back to where Tusk is against the European background. What can we expect from the future?

The statement from the European Commission from a few days ago (i.e., the Comission Communication issued December 11) indicates that this is the way to go, it speaks about those exceptions to rights. It’s against the Fundamental Rights Charter, but the Commission speaks about taking into consideration the circumstances of the hybrid war, that in this case states might implement some measures going against human rights, but they should be exceptional and of the last resort. So, this is the Commission kind of greenlighting the Polish initiative to become the vanguard of this “practical human rights approach”.

But it is also being said that during the Danish Presidency, which comes after the Polish one, they plan to present even bigger changes to the migration and asylum law in the European Union than the Migration Pact, and they will be going even further in terms of refugee and migrant rights violation: they will give Frontex more power, including the power to operate officially in third countries and to assist in deportations from third countries to other third countries; they want to make mass deportations easier than they are now; and they want to go further with the externalisation of migration.