Keeping score in a war is not an easy task. All manner of important data relevant to warmaking is obscured from open view. Much is hidden by the conscious effort of the warring parties for obvious reasons related to secrecy, but even behind the curtain of state security, armies do not always have a particularly accurate sense of how many casualties they have taken, what the strength of their constituent units are, and what the disposition of their forces may be. War is analyzed through a veil, and behind the veil is fog and confusion.

For the sake of convenience, therefore, position is often the most useful and popular marker of a war’s progress, but here one runs into another confounding factor: despite the great efforts that go into tracking and mapping fronts and movements and points of contact, territorial control is often a very bad proxy for who is winning or losing a war.

The best example of this, of course, is Germany. The Germans lost the two largest and most destructive wars of the 20th century despite fighting almost the entirety of both conflicts on foreign soil. In the first world war, the Germans were brought to surrender before any enemy forces ever made a penetration into German home territory, and in the second war they fought more than 90% of the war (from September 1939 to March 1945) on enemy territory, as it were, outside the borders of prewar Germany. The converse is, by extension, also true – specifically that the Soviet Union won the largest war in history despite doing most of the fighting in its own territory, with the destruction touching its own cities and people. Then, like a river that inexorably builds pressure until the dam can no longer hold it back, the Red Army burst forward in a colossal wave of conquest.

One of the core geopolitical results of the war – the enormous expansion of Soviet power and the creation of a communist quasi-empire – occurred in a very short and particular period of the war: roughly from July 1944 to March 1945. In the scope of a six year long conflict that engulfed much of the globe, this was an extremely rapid and totalizing act of empire building. While the powers of the world were all focused on their war efforts, Stalin conquered Eastern Europe in a “blink and you’ll miss it” campaign. In that brief and extremely violent period of Soviet initiative, virtually all the lands of the future Warsaw Pact fell under the control of the Red Army: Romania, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland, the Baltic States, and the western regions of Soviet Ukraine.

Thus, a new empire was built on the ashes of a dying one. In the states of Eastern Europe, the Soviet Union found easily workable political clay, in the form of states and polities that were either exhausted and weakened by war or else destroyed outright by German occupation. In some cases – as, for example, Hungary – the Germans even helped the Soviets by intentionally wrecking the governments of their former allies. In rolling back Hitler’s Eastern Empire, the Red Army uncovered a sort of political blank slate, where state power had already ceased to exist, allowing the Soviet Union to rebuild it in its own image.

Stay of Execution: Model at Warsaw

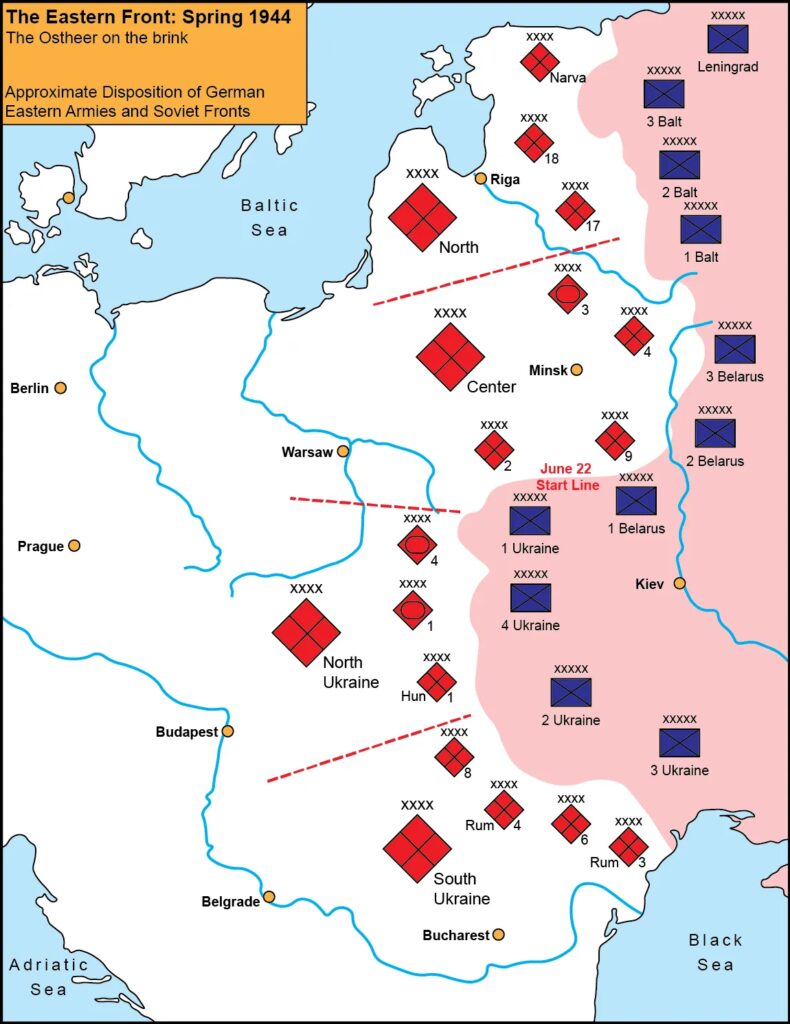

When we last left the Wehrmacht’s colossal Ostheer, or Eastern Army, it was in a state of operational free fall as its central position in Belarus (defended by Army Group Center) caved in under the pressure of the Red Army’s signature Operation Bagration. The Germans were reeling from one of the most colossal defeats in the history of warfare, and it was not immediately obvious that they would be able to find their footing. Indeed, a quick glance at the map suggested that Bagration – which had already swallowed up a whole slew of German corps and overrun Soviet Belarus – might only be an appetizer to even larger defeats to come.

The Soviet operational form – theoretically birthed in the interwar period, temporarily cast aside in the emergency of 1941, reborn in the campaigns of 1943, and now achieving its crescendo – emphasized the importance of “sequential operations”. This idea emphasized that modern armies had become so large, and their recuperative powers were so enormous, that the enemy could never be defeated in a single operation – even a victory as enormous as Stalingrad or Bagration ultimately was insufficient to sweep the Germans from the field. Therefore, it was necessary to prepare a sequence of offensive operations that could be launched one after the other, to keep the enemy off balance, deny him time and space to reconstitute forces, and maintain forward momentum.

The Wehrmacht got a particularly painful look at this methodology in 1944. Bagration had been bad enough – essentially evaporating most of Army Group Center and sending the remnants reeling back into Poland and East Prussia. For most armies, an operation of Bagration’s scale would have been a full slate for the summer, but the Soviets were just getting warmed up. They followed up the Belarusian maelstrom with an assault on Army Group Center’s neighboring formation, Army Group North Ukraine.

On paper, AG North Ukraine was the best equipped of Germany’s eastern formation. German planning throughout the spring and summer had anticipated the main Soviet blow to fall in this operational sector, which on the eve of Bagration had stretched roughly from Galicia and southern Poland down to the Hungary-Romania border. AG North Ukraine’s commander, Walther Model, had loudly insisted that his army group was the primary Soviet target, and used this to leverage German high command into allocating him much of the eastern army’s panzer force. Indeed, Model’s move to hoard armored forces throughout the spring had much to do with the parlous state of Army Group Center, and the corresponding ease with which Bagration eviscerated it.

But now, as Bagration began to run out of momentum, the Soviets really did put Model’s army group in the crosshairs with an enormous follow up offensive – the second phase of their summer blockbuster. Model’s army group consisted of two Panzer Armies (the 4th and 1st), and an allied Hungarian force guarding the southern flank. On paper, a pair of Panzer Armies was a formidable force, but like all German units at this stage in the war they were understrength, and by this point they were already bleeding strength as panzer divisions were scrambled north to try and slow down Operation Bagration.

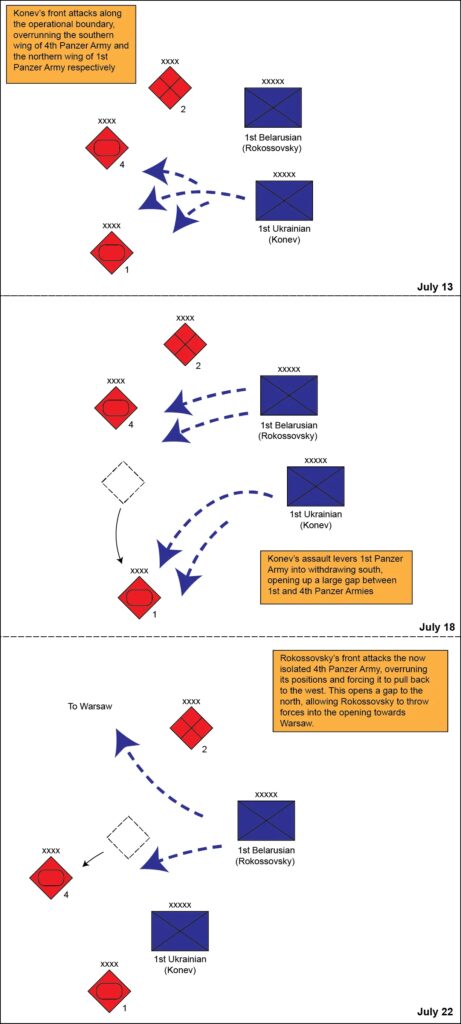

Arrayed against Model’s force were two Soviet Fronts (the equivalent of an Army Group) under a pair of the Red Army’s best operators. The lead off assault came on July 13, with Marshal Ivan Konev’s 1st Ukrainian Front forcing positions in the interstitial zone between Model’s two Panzer Armies. Konev’s intention was to split the two armies apart, force a penetration between them, and then curl into the rear to encircle one, or if possible both of them. Therefore, Konev’s initial assault was highly concentrated, with as much as 70 percent of his artillery and 90 percent of his armor assembled in a few narrow sectors selected for breaching.

With this level of force concentration by the attackers, there was really little that the Germans could do. Nevertheless, a somewhat lethargic and stiff German response helped make the disaster even worse. 4th Panzer Army headquarters initially believed Konev’s opening assault to be only a local attack – later defensively arguing that “there were as yet no signs of the attack being extended to other sections of the front” – and so attempted to respond with local counterattacks by its own reserves. As a result, by the second day of the Soviet offensive the Panzer Army had already committed all of its organic reserves while failing to withdraw from defensive positions that were already compromised. By the time they realized that Konev was launching a serious offensive operation, it was too late. Konev had already bashed into critical seams in the German front, turning his forces into a giant splitting wedge, in place to pry the whole front open.

As always, the price for lethargy among command staff is paid by the ordinary enlisted men. In this case, the unlucky grouping was German XIII corps, which was swallowed up with almost trivial ease near the city of Brody by great Soviet pincers as they barreled forward towards Lvov. The Corps did not receive orders to withdrawal until it was too late, and remained hung out to dry in an exposed forward position. By July 18, the 65,000 men of the Corps – including the 14th SS Volunteer Division Galicia, made up of Ukrainian volunteers – were firmly wrapped up in a tight pocket. A mere 5,000 of them, at most, would escape the pocket, and the remainder were killed or captured. The commander of the corps, General Hauffe, was captured, but stepped on a mine somewhere along the road as his Soviet captors marched him off to a POW camp. A horrible, but fitting end: with his entire corps either dead or captured, he somehow managed both.

The extermination of an entire corps put a grim cherry on top of the emerging disaster sundae. The Panzer Armies could no longer prevent the emerging penetration by Konev’s forces, and the only thing to do was withdraw. In this case, 1st Panzer Army conducted a tricky but skillfully conducted withdrawal to the south, breaking contact and swinging down into Hungary to escape the grasping tentacles of Konev’s front.

The problem, as always, was that by extricating itself from danger 1st Panzer had opened up an enormous gap between itself and its neighbor. 4th Panzer Army was still in place, but now with dangling flanks and all alone. Thus, when Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky’s 1st Belarusian Front launched its attack on July 18, 4th Panzer was in no position to resist. Already overmatched by superior Soviet fighting power, it faced annihilation now that its flanks were wide open. Like 1st Panzer, it was forced to withdraw, this time to the west.

What the Soviets had achieved with their enormous assaults on Army Group North Ukraine was remarkable. By precisely targeting the seams in the German formations, the initial attacks had pried open the German position like a clam, forcing the two panzer armies to retreat in opposite directions – the 1st pulling back to the south towards Hungary, and the 4th withdrawing westward towards Krakow. These diverging withdrawals opened enormous voids in the German line – the official German history of the war simply refers to this sequence of events as “the loss of a continuous front.” In a war where the enemy wielded vast mechanized forces, such gaps were fatal.

Rokossovsky and Konev had essentially overrun an entire German army group – and the best equipped group in the east, at that – in the space of about ten days, wedging the German line open and creating vast voids to drive into. Most importantly, Rokossovsky now faced one of the more tantalizing opportunities of the entire war. A great space now beckoned him to drive north towards Warsaw, and in his path was only the tired remnant of German second army – a force with no armor whatsoever, caught completely out of position.

Any wargamer could look at the map as Rokossovsky saw it and see that the opportunity to win a seminal, world-historical victory was now within reach. A sharp drive on Warsaw would put him in position to not only capture the city (a major transportation, administrative, and supply base), but also smash through the threadbare German 2nd Army and drive to the Baltic Coast. If he could achieve this, fully half of the German eastern forces would be encircled – the entirety of Army Group North (still fighting on the Baltic Coast) and everything that remained of Army Group Center. Rokossovksy now saw little standing between his powerful Front and one of the greatest encirclements – perhaps the greatest – of all time. No less than six German armies were sitting, naked and vulnerable, on the proverbial silver platter.

The Eastern Front was on the verge of total collapse. If Rokossovsky could bash through Warsaw (a seemingly simple proposition, given the enormous overmatch that he enjoyed over German 2nd Army), he would wipe out half the German eastern army and face no meaningful German forces between him and Berlin.

Enter Walter Model.

Model, as we have written before, was an unsavory and difficult character, even by the standards of late war German generals. However, his prowess as a defensive firefighter was undeniable, and here at the gates of Warsaw that was more evident than ever. Model could read the map just as well as Rokossovsky could, and instantly knew that if 2nd Army was overrun the entire front was liable to begin collapsing.

Fortunately for Model, he had something that no other German general had enjoyed to this point in the war: autonomous theater level command. He’d begun the summer in command of Army Group North Ukraine, but as the situation got worse and worse Hitler made the decision to give Model Army Group Center as well, making him the first commander to enjoy the command of multiple army groups at once. Model also had a unique relationship with Hitler, enjoying something that can even be called “trust”, which meant that Model uniquely did not feel the need to constantly ask Hitler for permission to make operational decisions, and was not reprimanded for this temerity.

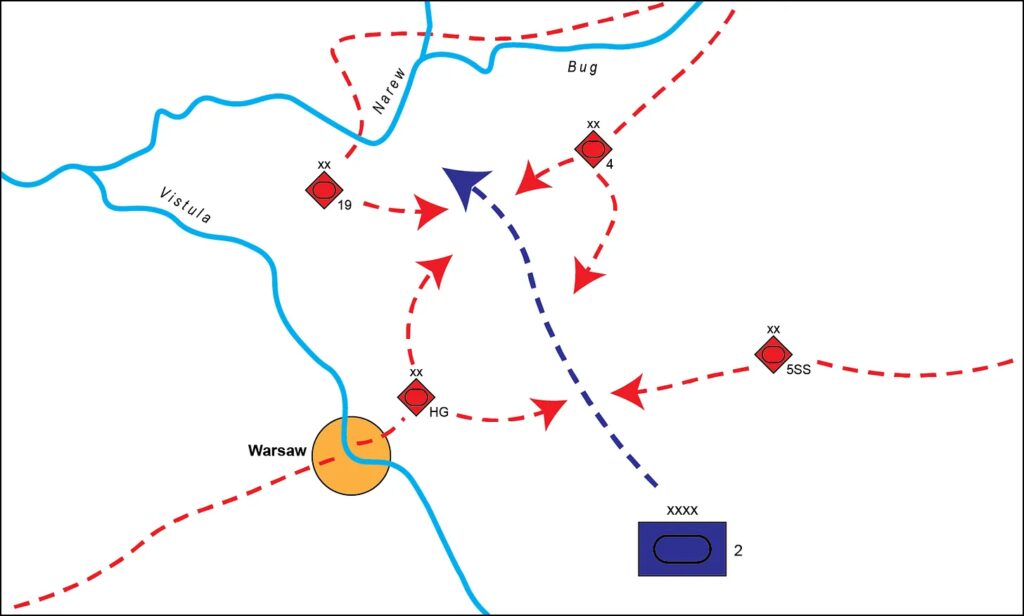

Thus, as Rokossovsky was driving on Warsaw in full fury, Model was able to exercise a genuinely unique level of theater-wide command authority. He used these powers to immediately begin scrambling Panzer divisions to Warsaw for a counterattack. There were four available – the 4th, 19th, and 5th SS Panzer Divisions were hastily pulled out of their spots on the line and railed towards Warsaw at warp speed, while the Hermann Göring Panzer Division was rushed in from Italy. Taken together, these four divisions possessed just under 300 armored vehicles, but under Model’s auspices they were sufficient to save the Germans at Warsaw.

The Warsaw Counterattack had a sort of breathless perfection to it. The platonic ideal of German warfare, as perfected by the halcyon commander Helmuth von Moltke, was “concentric attack” – independent formations attacking the enemy from multiple directions. For nearly a century the Prusso-German command had been attempting to replicate this scheme with varying levels of success. At Warsaw, on August 1, 1944, Model put on one of the last great demonstrations, with a sequence of Panzer divisions scrambling in – seemingly from nowhere – and taking the onrushing column of Rokossovsky’s 2nd Tank Army from multiple angles. In the case of the Hermann Göring Division, the Panzers more or less went directly into battle after disembarking their trains. It was a close run thing – a seeming miracle that Model managed to get enough forces deployed in time – but it was enough. Taken by surprise from multiple directions, Rokossovsky’s army would lose some 550 of its 800 armored vehicles in the ensuing firestorm, forcing him to withdraw to refit.

In the grand scale of this war, the counterattack at Warsaw can seem very small, even though, with over 1,000 armored vehicles mixing it up in a small area, it was in fact a substantial tank battle. Certainly, the Soviets were shocked to come under tank attack. Rokossovsky was driving his tankers like mad for the twenty mile stretch where the Bug, Narew, and Vistula rivers intersect. Once he secured the crossing of these rivers, he anticipated a drive to the Baltic with little resistance, and the entire German position would fall into his lap. The failure of this maneuver is owed singularly to Model’s lightning quick reaction and determination to pull Panzers to Warsaw as fast as possible, no matter what.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Model’s actions both saved the Eastern Front from a premature collapse and doomed Warsaw to destruction. With Soviet momentum at last dissipated and Rokossovsky’s front working to consolidate its positions, Model was free to turn his attention to Warsaw itself, where the Polish Home Army had launched an uprising in anticipation of immanent German defeat. They, like Rokossovsky, did not know that Model had multiple armored divisions slated for immanent arrival, and were thus bitterly disappointed when their efforts to liberate the city internally collapsed alongside the Soviet offensive. The German response was genuinely horrifying, with the Warsaw garrison destroying fully 85% of the city’s buildings in the following two months.

The fact that the Germans were able to almost completely destroy one of Europe’s major cities while Red Army forces were stationed only a few miles away has led to one of the enduring tropes of the war: that the Soviets deliberately sat by idly, allowing the Germans to wipe out independent Polish resistance (thus saving the NKVD the trouble of having to do the job). While there is some element of truth here – the Red Army did not attempt to intervene as the Germans brutally put down the Polish resistance – their crime seems to have been simply a matter of choosing military prudence over humanitarian sympathies. The Red Army had, in the space of about six weeks, advanced some 450 miles, and then suffered a defeat in which their spearhead tank army lost nearly 75% of its vehicles. After Model’s victory – and the phenomenal dimensions of the Soviet advance – it is not particularly clear what the Red Army might have done to intervene, sitting as they were at the far end of their logistics after weeks of hard fighting.

In either case, Warsaw today remains a veiled and gruesome memorial to Model’s victory, and his miraculous rescuing of the eastern front in 1944. The Warsaw that exists today is not real. It exists, of course, with real people occupying physical structures, but the city itself is a replica – a cold war era reconstruction designed to look like the old city. The facsimile is a monument to Model’s “greatness.”

Model’s scramble at Warsaw saved the Eastern Front – for a time. At the moment of maximum danger, he recreated a classic German tactical schema – the blueprint of Konnigratz and Tannenberg – with a swarming, concentric attack by hard hitting battlegroups. Even with the colossal strategic overmatch that now prevailed, Soviet tankers at Warsaw were unable to cope with this basic formula (or the German “Big Cat” tanks at close range). Model’s performance at Warsaw – and in stabilizing the western front in the coming months – generally earn him very high marks as a defensive specialist and praise for his operational acumen.

And yet, Model’s art of war held no prospect of victory. It was a defensive exigency, designed to cope with major emergencies. The elements of Model’s approach – well timed counterattacks, jealously hoarding a mobile reserve, scrounging up rear area personnel to fill out the front – these were all firefighting measures which lacked an offensive component, and were always ultimately self-defeating. They could yield impressive results in that they staunched heavy bleeding, but an army that is rounding up mechanics, administrative and logistics personnel, technicians, and drivers to fill out its infantry formations is an army that is cannibalizing itself, and in the long run this cannot lead to victory. The Soviets had still pushed the frontline forward by hundreds of miles, mauled or encircled half a dozen German armies, and bent the eastern army beyond repair. Model’s victory thus served only as a delaying action of sorts, and a bitter one at that for the residents of Warsaw.

The Great Shattering

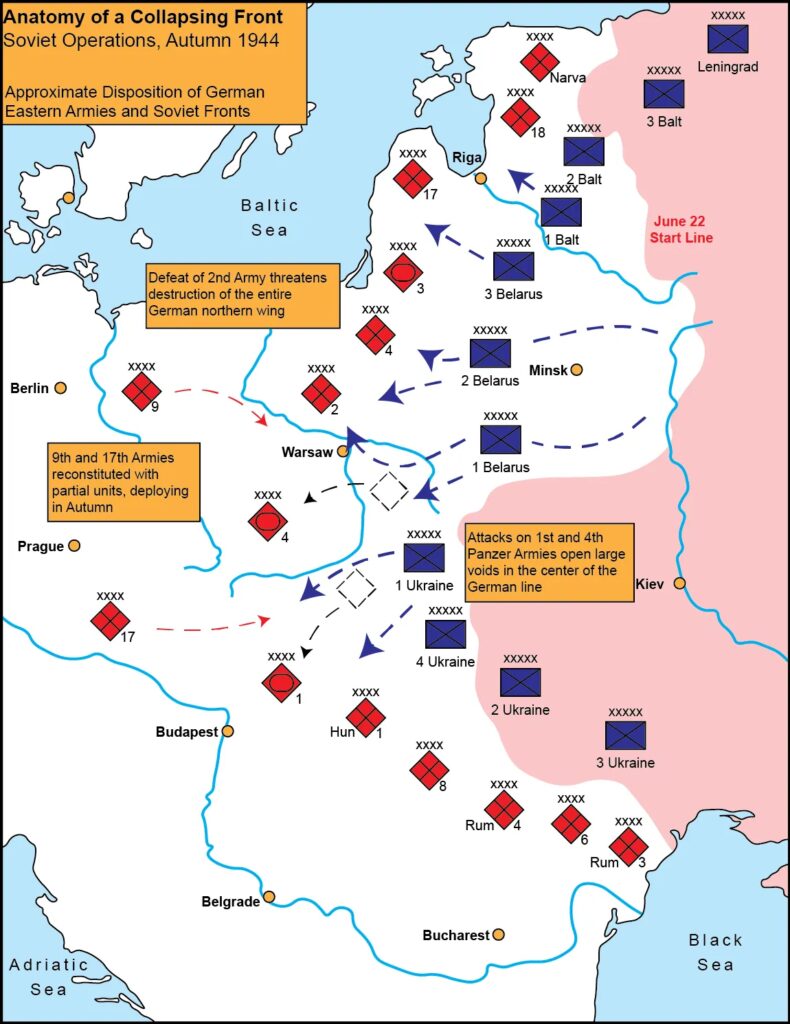

If German high command thought that Model’s counterattack at Warsaw might have bought them some respite, they were sorely mistaken. Soviet offensives to that point had focused heavily on the central sectors of the front, in Soviet Belarus, Western Soviet Ukraine, and Poland. This had pushed the center of the front far to the west, while the Germans continued to hold eastern positions on the wings of the front. So while in the center the Soviets had advanced all the way to the gates of Warsaw, the Germans still had major field formations nearly 300 miles to the east, including in the Narva Isthmus in Northern Estonia, and on the shore of the Black Sea in Romania.

Soviet activity throughout the autumn of 1944 would focus on caving in these positions, and would achieve extraordinary results. No fewer than four German field armies would be encircled, and Germany’s remaining Axis partners would be run out of the war. The Red Army would capture many of Eastern Europe’s great cities: Bucharest on August 31 and Belgrade on October 14, with Budapest besieged in December. What remained of Hitler’s eastern empire was dismantled by force of arms, and replaced with a more powerful Soviet Empire.