Most people, if they were asked to list the great seafaring peoples of history, or more specifically the great naval fighting traditions, would come up with a fairly uniform list. There are obviously the two great naval powers of modernity in the British Empire and the United States (though the latter is now not without challengers), and the navigators of the first transatlantic empires in Portugal and Spain. China had a brief period of prolific shipbuilding and navigation in the early modern period, but was disinterested in trying to leverage this into durable power projection. Modern China seeks to rectify this missed opportunity. A deeper dive into the mental archives might churn up the ancient Phoenicians, or perhaps the Genoese and Venetian city states that dominated the Mediterranean in the early modern period. There are those wonderful Vikings, who managed to reach the Americas in their open hulled longboats, and terrorized and colonized much of Europe with their nautical reach. Few, however, would immediately think of the Romans.

The Romans are by convention and by reputation a great land power. The iconic system of Roman power projection was the legion, famed for its discipline, its versatility, and its great prowess of combat engineering – throwing up roads, fortresses, and fortified camps with ease at it trampled enemies from Britain to Syria. In the popular imagination, the Roman Navy is a mere footnote.

The relegation of the Roman naval tradition to the footnotes is a rather interesting phenomenon. It stems, in fact, from a naval victory so totalizing and complete that Roman control of the Mediterranean became an established fact of life. Rome’s domination of the sea became so total that for many centuries it was as implicit and unchallenged as the breathability of the atmosphere. Rome swept all challenger navies from the Mediterranean and never let them return, as long as the empire remained strong. Rome is viewed fundamentally as a land power because it obliterated all naval rivals, so that its only military challenges lay on its peripheral land borders.

In short, the Roman navy is often forgotten simply because it did its job so well. The total victory of Rome at sea gave the Romans the wherewithal to say, without any real hubris or exaggeration, that the Mediterranean was Mare Nostrum: Our Sea. The transformation of the Mediterranean – a crossroads of civilizations that had once been prowled by many rival navies – into a pacified internal zone of the Roman Empire is at the same time a largely forgotten reality – so true that it is taken for granted – and a major source of Roman imperial strength, which let them transport foodstuffs, material, and men around the empire with great efficiency and the assurance of safety.

But the Mediterranean was not always the Roman Sea. Mare Nostrum was not given. It was taken, and the taking required an exorbitant expense and a great loss of life. The watershed event in this saga was the great contest with Carthage – a genuine great power with a strong naval pedigree and tradition of its own – in the Punic Wars. With great effort and difficulty, the Romans slowly but surely exterminated the Carthaginian Navy, and then Carthage itself, in one of the cornerstone acts of Roman empire building and the greatest naval war of the ancient world. In repeated violent clashes on the Mediterranean, the Romans won their sea by their willingness to fill it with the blood of their sons.

Winning the Sea: Rome and Carthage

The Carthaginians have gone down in history as a geopolitical nemesis and foil. Rome, for obvious reasons, is the pivot of many centuries of western history, and as the most hated and dangerous Roman rival, Carthage is usually discussed only in the context of its long, bloody, and ultimately unsuccessful struggle with the Romans. While the naval war with Rome is obviously our main interest here, a few words about the Carthaginians themselves are perhaps worth our time.

The ancient city of Carthage lay on the coast of modern day Tunisia very close to the contemporary capital of Tunis, near the strait that separates Sicily from Northern Africa. Although it lay on the continent of Africa and in the same maritime strategic space as Rome, it was neither European nor African in its nature, but rather Canaanite. The city was founded just before 800 BC as a colony of the seafaring Phoenician people, who from ancient times lived on the coast of the Levant. The particular founders of Carthage were colonists from the Phoenician city of Tyre, in modern day Lebanon.

The Phoenicians were a prodigious people, famed for their navigational skills, mercantile predilections, alphabet, and shipbuilding, but they had the misfortune of being a fundamentally maritime people living near the heartlands of the great archaic land empires. From the 8th Century onward, the Phoenicians were frequently dominated by first the Assyrians and later the Persians, and the fading of Phoenician autonomy (combined with the great distances of the sea) led to increasing Carthaginian independence. The result was a unique Carthaginian civilization, Canaanite in its ethnic origins, with its own systems of proto-Republican government and religion which were alien to the Romans and other peoples in the Western Mediterranean. The Carthaginians, like other Punic peoples (the favored term for the Phoenician transplant civilizations in the west) worshipped gods of the Canaanite religion, including the Baal of biblical infamy. In this sense they were cultural alien both to their Roman rivals and to the African tribes that inhabited the lands around them.

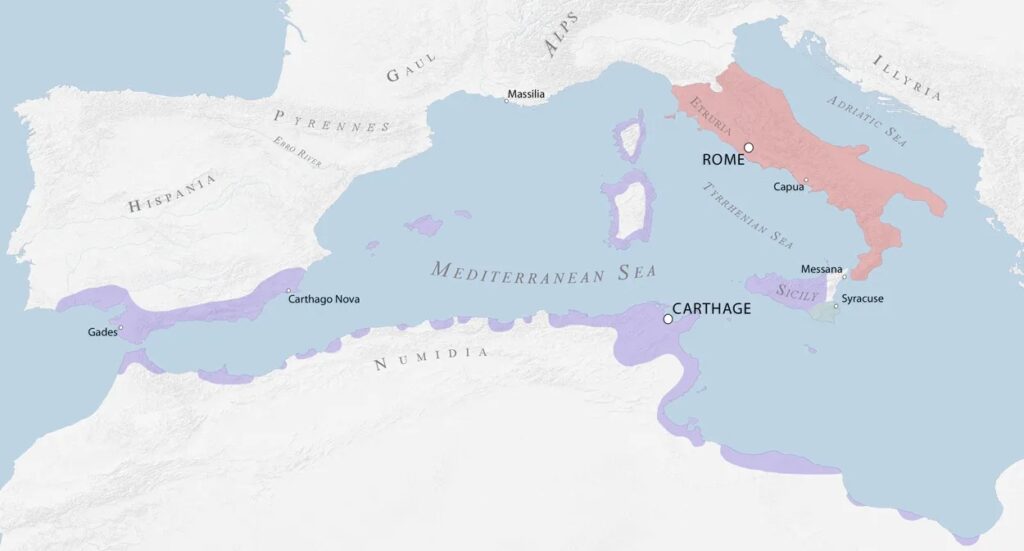

By the third century BC, as Rome consolidated its control of the Italian peninsula, Carthage had carved out powerful position for itself around the rim of the Western Mediterranean, with a web of client states, colonies, vassals, and allies along the North African Coast, in Iberia, Sicily, Corsica, and Sardinia. The Carthaginian Empire, like many archaic empires, was not so much a discrete territory subject to direct control as an extension of diplomatic and mercantile influence, bringing in tribute and trade to Carthage, held together by Carthage’s powerful navy and by a network of Carthaginian outposts, fortresses, naval bases, and colonies.

In looking at a map of the Western Mediterranean on the eve of the Punic Wars, it may seem that war was inevitable given how close Carthaginian influence had come to Italy. Perhaps the Romans coveted Sicily, or feared Carthaginian naval incursion into Italy? In fact, there was initially little Roman interest in either Sicily or a broader war with Carthage. Rather, the Punic Wars, which would engulf the Mediterranean for a century and lead to the complete destruction of Carthage and its civilization, began practically by accident, and offer an instructive example of how quickly a conflagration can burn out of control.

The great war between Carthage and Rome was started by neither power, but rather by an unemployed company of Italian mercenaries calling themselves the Mamertines, or Sons of Mars. Out of work and bored, they decided to pass the time by occupying the strategic city of Messina, which sits on the strait separating Italy and Sicily. The occupation of this valuable port by a band of rogue mercenaries raised the alarm of Syracuse – a kingdom of Greek transplants in southeastern Sicily which was the only notable independent state in the Western Mediterranean aside from Carthage and Rome.

Because Syracuse was a sort of distant third wheel to the Romans and Carthaginians, the Syracusan King, Heiro II, opted to appeal for aid in ousting the Mamertines from Messina. His call was answered in 265 by a Carthaginian fleet, which arrived and swiftly took custody of Messina and brought the mercenaries to heel. This was the spark that set off the great fire.

The Romans, who at this point were still largely contained within Italy, had never shown any great interest in expanding their dominions to Sicily or in fighting a war with Carthage, but the sudden appearance of a Carthaginian force in Messina was greatly alarming, and after some heated debate it was decided to intervene on behalf of the Mamertines (who had appealed to Rome for help, citing their status as Italians) and eject Carthage from Messina. No one seems to have seriously considered the possibility of a long war, but only a short and decisive action to prevent the Carthaginians from consolidating a base so close to Italy.

In 263, Roman forces crossed the narrow strait to Sicily, occupied Messina, and marched south, forcing Syracuse to capitulate and defect from its alliance with Carthage. King Heiro agreed to pay a symbolic war indemnity, become a Roman ally, and provide basing and supplies for the Roman army in Sicily. The Romans then got the jump on the Carthaginians by rapidly marching to the city of Agrigentum, in southern Sicily, where they laid siege to it and eventually sacked it – a satisfying victory, no doubt, but one which greatly hardened the Carthaginian stance and made a full scale war for Sicily all but inevitable.

The beginning of the war therefore clearly favored the Roman preference for high intensity and decisive warfare – largely as a result of strategic surprise and aggression which caught the Carthaginians on the back foot. Unfortunately for the Romans, Sicily was not a place where this type of war could be waged indefinitely. Sicily is (and was) mountainous and road poor, making supply and maneuver difficult. The terrain, combined with Carthage’s preference for a defensive and patient strategy, denied the Romans the opportunity to fight decisive set piece battles and massive sieges. In the following 23 years of war in Sicily, the Romans and Carthaginians would fight only two conventional set piece battles. The remainder of the land campaign would be a frustrating grind characterized by ineffective sieges, raiding, interdiction, and small skirmishes in the mountainous terrain.

The Romans found the pace and nature of the fighting in Sicily immensely frustrating and indecisive, and were particularly flummoxed by their inability to successfully siege the key Carthaginian strongholds on the coast. Because these port cities were easily supplied and reinforced by the powerful Carthaginian navy, conventional Roman siege tactics were ineffective. It was inevitable, of course, that a war for an island would eventually revolve around the sea, however much the Romans may have wished to leaned on the strength of their legions.

It is difficult to emphasize just how little experience the Romans had with naval operations or shipbuilding. They had briefly maintained their own fleet at the turn of the century, but after a defeat on the water at the hands of the small city state of Taranto in 282, they had disbanded their navy and instead chose to conscript the vessels of allied cities as naval auxiliaries – indeed, the Roman army that went into Sicily in 263 was transported and supplied by these satellite navies. Facing the prospect of a wider naval struggle in the seas around Sicily, however, the Romans took the fateful leap. In 260, after three years of stalemate on land, the Romans built their first navy.

By the 3rd century, naval combat had changed from the era of the Athenian trireme in ways that were meaningful, but not radical. Triremes were still in service, but they no longer formed the mass of the battle line, as they had been supplanted by the much larger quinquereme – which, as the name suggests, now had a bank of five rowers rather than three. It was previously taken at face value that there were five separate banks of oars on each side of the ship, but modern scholarship has firmly established that this would have been deeply impractical – making the ship extremely top heavy and raising the likelihood of the mass of oars becoming tangled or fouled. It is now accepted that the quinquereme – sometimes simply called the “five” – instead had three banks of oars like the trireme, but with five associated rowers. The bottom oar would have been manned by a single rower, with the upper two rowed by two rowers each. Thus, a Roman five would have been propelled by a crew of some 280 rowers, as opposed to the 170 men who rowed an archaic trireme.

The addition of more rowers was not an innovation to produce a faster ship. On the contrary, the additional propulsion was desirable because it powered a ship that was much taller, heavier, more seaworthy, and more sturdily built. Triremes continued to be much the faster and more maneuverable vessels, but they were dwarfed by the quinquereme and found it impossible to grapple with the larger vessels in combat. The height and deck space of the quinquereme were particularly important in boarding actions, in that they allowed the ship to carry a much larger complement of infantry on the deck. Whereas an ancient trireme would frequently have as few as 20 marines on deck, the Romans would pack a quinquereme with as many as 120 legionaries. The smaller but faster trireme, now badly outmuscled in pitched battle, took on reconnaissance duty.

Therefore, when the Romans set out in earnest to build a navy, the quinquereme was to be the mainstay of the fleet. The Senate resolved in 260 to fund the construction of a 120 vessel armada, of which 100 were quinqueremes and the remainder triremes. Polybius records that a shipwrecked Carthaginian quinquereme was recovered and reverse engineered as the model for the Roman fleet – consequentially, there is little reason to doubt that the vessels used by the warring navies were of very similar construction. The decisive factor would be training, tactical innovation, and the caprice of battle.

The Roman historian Pliny made a particular point to note that this first Roman fleet was completed in only 60 days. This has at times been taken as an exaggeration meant to emphasize the usual Roman point of pride in their engineering prowess, but modern archeological finds have deduced that the Romans managed to assemble a fleet very efficiently, whether 60 days is the appropriate figure or not. The ribs and beams of sunken Roman vessels from this era are inscribed with notched marks that indicate part numbers and a design template, indicating an assembly line process of mass production.

In any case, the Romans managed to rapidly assemble and crew a fleet, and put a detachment to sea to take the newly recruited and inexperienced rowers through their paces.

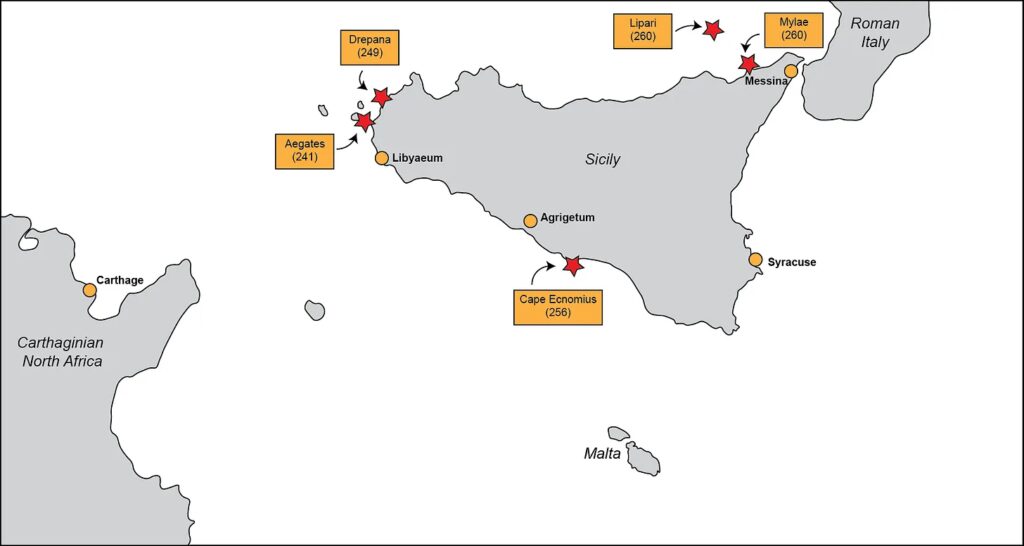

The early naval engagements of the First Punic War were a demonstration of a timeless axiom in naval combat – namely, the importance of staying apprised of the enemy’s position and striving to keep one’s fleet on station together in a mass. Both the Carthaginians and Romans suffered early defeats when a small detachment of their fleets were surprised by larger enemy forces. The Romans lost a small force of 17 vessels (and had a consul go into captivity) when they were ambushed and trapped in a harbor, and several weeks later the Carthaginians lost several dozen ships when a raiding detachment unexpectedly bumped into the main Roman fleet off the northern coast of Sicily.

These were small and relatively chaotic engagements, but they neatly impressed upon the Romans that, although they had successfully copied the Carthaginian quinquereme design, their rowing crews and captains were too inexperienced to hold up against the enemy in maneuvering fights. They had great difficulty ramming and grappling with the more agilely handled Carthaginian ships, and this deficiency led to a critical early war innovation that would prove absolutely essential for allowing the novice Roman navy to compete in early battles.

This new Roman weapon has gone down in history as the Corvus, which means crow – although none of the ancient sources use this term. The identity of the inventor is unknown, which suggests that he was not Roman, as Romans liked to claim responsibility for their achievements. In any case, the corvus was a boarding plank, some four feet wide and 36 feet long, mounted on the bow of the vessel on a swiveling platform. Raised into attack position via a pulley, the swiveled mount allowed the corvus to swing about on either side of the ship, where it could be dropped on any enemy vessel which came too close. The signature feature of the corvus was a curved spike on the underside of the plank’s outward end, which would bite into the deck of the enemy vessel as it dropped and prevent it from getting away. This curved hook, which resembled a bird’s beak, is likely where the name originated.

The corvus gave the Romans an extremely powerful tactical expedient which allowed them to, in essence, snare any enemy vessel that came within reach of the bow. When an unfortunate Carthaginian vessel came too close, the corvus could rapidly swivel into position, drop with a heavy thud, and grip the enemy deck with its underside hooks. The enemy would have no time to react or dislodge the hook before Roman legionaries and marines came rushing down the ramp, giving the Romans the exact type of fight that they liked best – an infantry fight in close quarters.

This was a powerful tactical method, and it proved to be one that the Carthaginians never did develop a reliable counter to. Most importantly, the corvus greatly simplified the task of the Roman crew – rather than try to match the more experienced Carthaginians in maneuvers, they only had to try to keep the enemy ship away from their stern, since any attack on the bow of the ship would bring the corvus into play. It was much more difficult to ram the enemy in the aft flank than it was to simply get close and grab the enemy with the corvus. We should note, however, that the corvus was not without drawbacks, some of them quite severe. The weight of the corvus made Roman ships even more ponderous and less maneuverable, and in particular they made the ships very top heavy and vulnerable to rough weather. In the short term, however, they provided a powerful tool to balance the odds against the veteran Carthaginian fleet.

The first use of the Corvus was a rousing success. The Roman fleet intercepted a raiding Carthaginian armada near the port of Mylae in northern Sicily, joining the first pitched naval battle of the war. The fleets were of roughly equivalent size – perhaps 120 vessels each – but the Carthaginians were taken aback by their first encounter with the corvus, which time and time again crashed down and snared their unlucky ships, opening the path for a flood of Roman infantry to board. More than 30 Carthaginian ships were captured, and another dozen sunk, in Rome’s first victory on the water. However, the faster Carthaginian fleet was able to disengage and escape with all its remaining vessels, while the heavier Roman ships – burdened with the corvus – were unable to pursue.

For the Romans, the Battle of Mylae late in 260 proved that they could fight the Carthaginians on the water and win, despite the superior nautical pedigree of the enemy. The Carthaginians, for their part, probably felt that the Romans had been lucky, surprising them with a novel tactic. The corvus was deadly, yes, but the battle had also proven that the Carthaginian ships were still faster, more agile, and better handled. In any case, the battle confirmed that the sea would now be fully and hotly contested, and would become the decisive theater of the war.

Beginning the following year, both sides would begin pouring vast resources into shipbuilding in the aims of achieving a decisive advantage on the water. The Romans remained frustrated by a grinding stalemate in Sicily, but unexpectedly encouraged by their success in naval engagements. This led the Romans to renew a naval-oriented strategy, and in 256 they launched a campaign to mount an amphibious invasion of Carthaginian North Africa, in the hopes of threatening Carthage proper and forcing a surrender. It was this expedition that set the conditions for the largest naval battle of the war, and indeed of all time.

The Big Brawl at Ecnomius

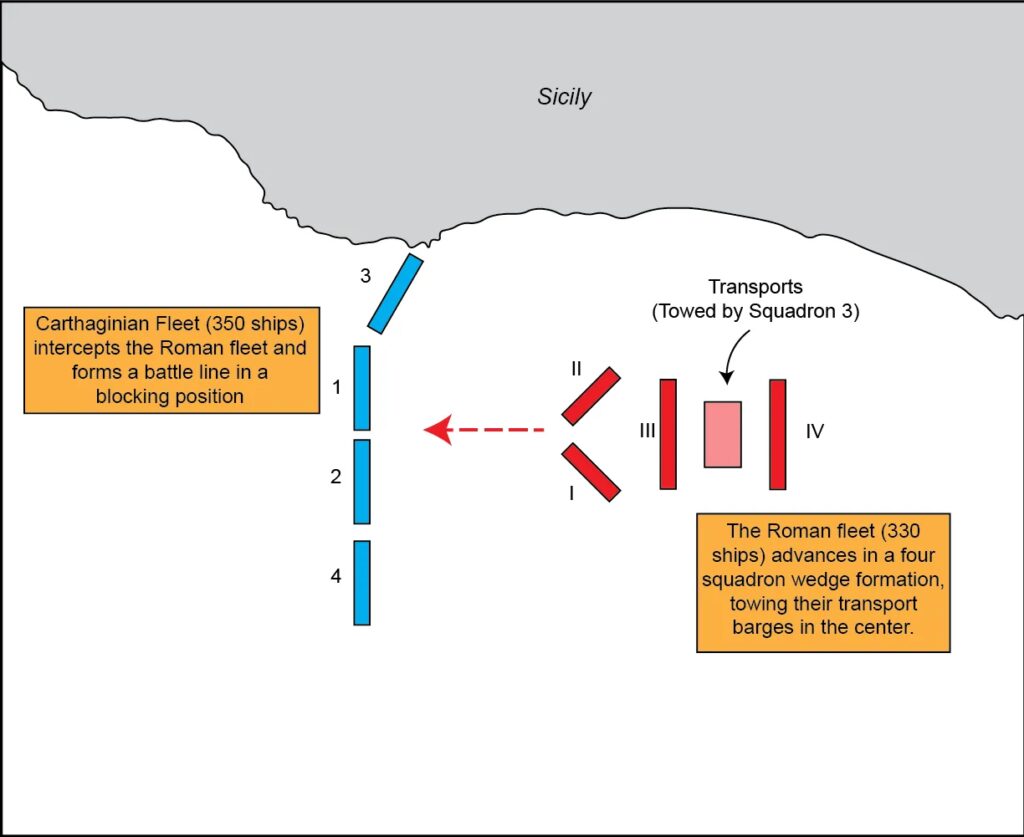

Late in the spring of 256, an enormous Roman fleet mustered at the mouth of the Tiber and set out for North Africa. The force was a truly imposing armada: 330 warships, almost all of them quinqueremes, under the command of Rome’s two consuls for the year – Marcus Atilius Regulus and Lucius Manlius Vulso – each of whom sailed in a colossal six-banked hexareme flagship. In addition to this imposing accumulation of naval combat power, they brought with them a large number of transport vessels which carried supplies, horses, and fodder for the landing army. Though the number of transports is not identified by Roman sources, it must have been substantial given the size of the force.

Intercepting and combatting such a fleet would require virtually all of Carthage’s naval assets. It was therefore fortunate that they were alert to Roman intentions, and conducted a near simultaneous counter-muster of the fleet under the command of generals Hamilcar and Hanno off the coast of Sicily, including not only the ships already active there but also a fresh fleet raised in Carthage. In total, the Carthaginians were able to accumulate some 350 vessels.

The amount of fighting power now operating around Sicily was genuinely astonishing, not just for the archaic era but for any period of history. Each Roman quinquereme carried 80 legionaries in addition to the standard complement of 40 marines, meaning that the armada’s infantry component alone was nearly 40,000 men. When the rowers and deck crews of the massive ships were added in, one calculates that the Roman fleet had a credible headcount of nearly 140,000 men. The historian Polybius recorded that the Carthaginian fleet contained 150,000 personnel – a number that is broadly accepted, given the similarity in the size of the fleets, though it is possibly too high as there is some reason to believe that the Carthaginians carried fewer infantry on board. But with nearly 300,000 men involved, the ensuing clash between these fleets was, most likely, the largest naval battle of all time when judged by the count of personnel.

The Carthaginians had several important advantages to lean on, most of them related to the mobility of the Roman fleet. Roman ships at this point continued to utilize the corvus in combat. Although this remained a deadly expedient in battle, it gave the Carthaginian ships a substantial edge in maneuverability and speed. More importantly however, the weight and imbalance of the corvus made Roman ships rather suspect in choppy seas – a fact which strongly encouraged Roman fleets to stay as close to land as possible. Furthermore, the Romans had a large number of transports in tow – quite literally, in fact, as the transport barges lacked propulsion and had to be pulled behind the warships.

Burdened by their transport barges and destabilized by the corvus, the Roman fleet was therefore unable to take a direct or rapid route to North Africa. Instead, they had to partially circumnavigate Sicily, sailing within eyeshot of the coast, in order to cross over to Tunisia at the narrowest point of the straits. The ponderous, plodding nature of the Roman fleet gave the Carthaginians strong prospects of intercepting it mid-voyage and bringing it to battle. This is precisely what they did.

As the mighty Roman armada worked its way across the southern coast of Sicily, making a westward course towards Africa, they saw rising on the horizon an equally imposing Carthaginian fleet awaiting their arrival. The greatest collision of nautical fighting power in the history of the Mediterranean was now imminent, off the coast of Cape Ecnomus.

The course of the battle was to be determined first and foremost by the unique arrangement of the fleets as they approached each other. As the Romans were winding along the coast, they kept a tight and compact formation. The 330 warships were divided roughly into four large divisions, commonly called squadrons in the historographic parlance, though this was not a Roman word. The Roman sailing column formed a sort of wedge, with two squadrons leading in oblique echelon. Behind them, the third squadron sailed in a line, towing the vast cloud of transport barges behind them. The final, fourth squadron sailed at the back as a rearguard and reserve.

In contrast, the Carthaginians were arrayed in a conventional battle line, with their left wing angled towards the coast. The battlespace thus had the coast of Sicily as a boundary to the north, and open sea to the south. The dynamics of combat between these fleets were by now well understood. Carthaginian ships could be badly mauled by the Roman corvus and boarding parties if they fought a congested, head on battle, but their superior maneuverability gave them a strong advantage if the battle could be widened into the open sea.

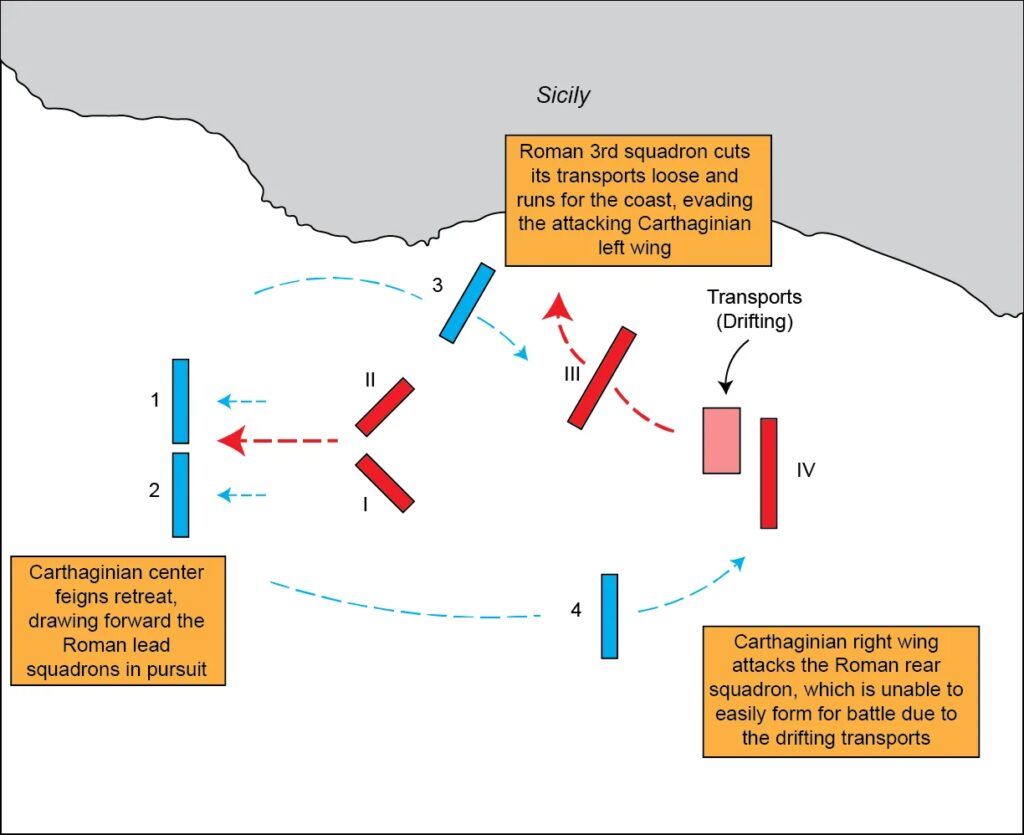

The Carthaginian battleplan, therefore, hinged on an attempt to break apart the compact Roman formation and create a more open, fluid battle where superior Carthaginian mobility could carry the day. The centerpiece of this effort was a feigned retreat by the Carthaginian center as the fleets approached each other. As the Roman wedge approached, the Carthaginian center immediately began to back water, opening up a yawning void in the middle of their line. The two leading Roman squadrons, each personally led by one of the consuls, immediately lunged forward in pursuit. Both sides had now agreed to a mutual gambit. By breaking their front open through the withdrawal of the center, the Carthaginians gave up the integrity of their battle line – but by surging forward to exploit this situation, the forward Roman squadrons abandoned the more vulnerable rear of the column, which was still encumbered by the towed transports.

The Carthaginian trap began to spring shut as the lead Roman squadrons eagerly came forward to attack the withdrawing Carthaginian center. While their center backed water, the Carthaginian wings shot forward, bypassing both their own center and the advancing Roman lead elements. The plan, evidently, was for the Carthaginian wings to rush forward to attack the rear half of the Roman column as it was still attempting to deploy into a battle line. On the Carthaginian left wing, their ships skirted past the coast and prepared to set on the Roman 3rd squadron, while the right wing – which lay on the open sea and contained the fastest and most experienced Carthaginian crews – made a dash for the rear of the Roman column.

Things very well may have gone very badly for the Romans at this juncture. Their 3rd Squadron, which had been towing the transport train, had to disengage their tows before they could even begin to maneuver, while the 4th squadron at the rear could not cleanly enter the battle because all of the transports were in their way. On paper, it certainly looked like the Carthaginian wings were going to slam into the Roman column while it was immobile and disorganized.

Disaster was averted for the Romans thanks to the timely and lithe reaction of their 3rd squadron. Seeing the Carthaginian left wing bearing down on them, they hastily cut their transports loose – then, rather than accept a fight with the Carthaginians in the open water (with the transports at their back, hampering their mobility) their captains made the ingenious decision to run for the coast. This apparently caught the Carthaginians by surprise, for despite the superior speed and maneuverability of their ships, they were unable to snare the Romans into a fight or intercept them before they could reach the coast.

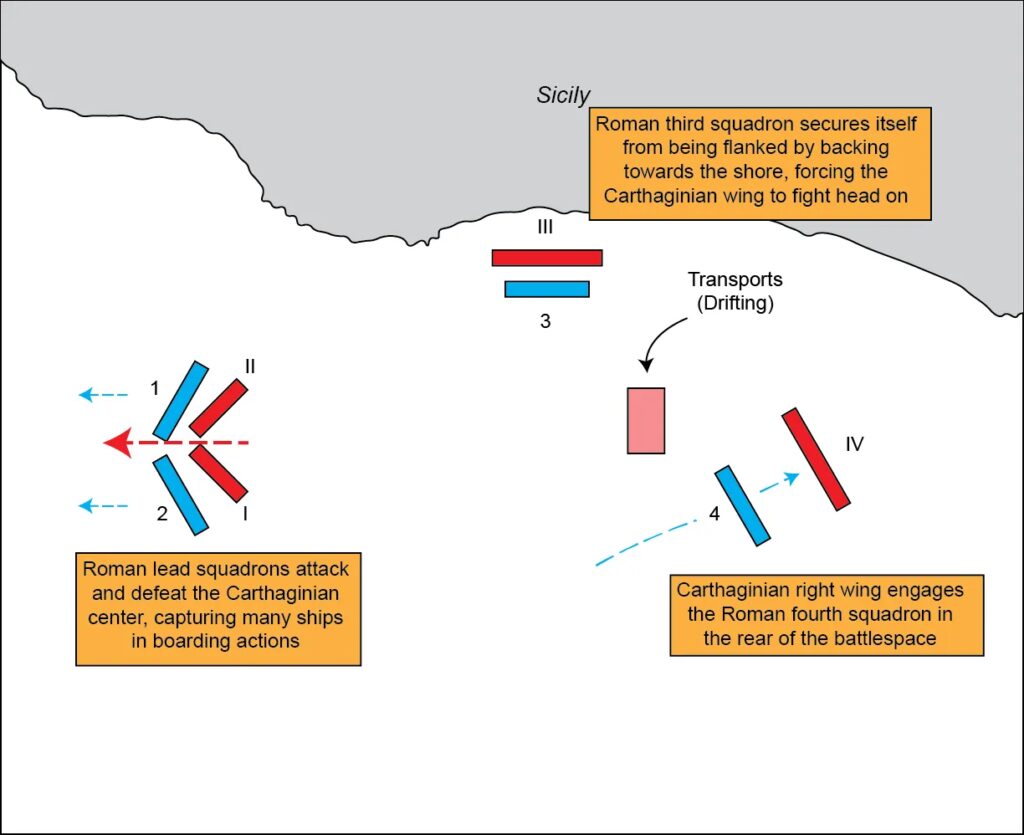

The decision by 3rd squadron to run for the coast was, in a word, brilliant. Out in the open water, the Romans were vulnerable to the agile Carthaginian ships, which could dash in and out looking for opportunities to ram the Roman vessels in the stern. Upon running to the shore, however, 3rd squadron turned about and backed in, so that the sterns of their ships were pointing towards the coast and the bows out towards the sea. With their rear snuggled in against the coastline, it became impossible for the Carthaginians to flank or envelop them. Instead, they faced a wall of ships facing outward, with the deadly corvus waiting to grab any Carthaginian ship that came to close. This neutralized the entire maneuver of the Carthaginian left wing and turned it into an ugly close quarters scrum.

Still, the Romans were not in a particularly cozy spot. Their transports were now adrift, having been cut from their tows. The Roman 3rd squadron was defending itself capably, but it was still pinned against the shore and unable to actively intervene in the larger battle – more importantly, it had voluntarily backed into a corner and would be destroyed if the larger battle went poorly. Meanwhile, the rearmost Roman squadron had great difficulty forming up a battle line due to the drifting transports in the way, and found itself hard pressed and facing likely defeat in the open water at the hands of the Carthaginian right wing.

The battle was decided, then, by the collision of the centers. After backing water to draw the forward Roman squadrons in, the Carthaginian center joined battle and found, very simply, that they did not have an adequate counter to the corvus system. While several Roman ships were successfully rammed and sunk, the Romans time and time again managed to snare enemy ships with the corvus. The all-too familiar horror replayed itself dozens of times: the sudden swivel and drop of the boarding plank, the splintering crash as the bronze spike stabbed into the deck, and the ensuing rush of heavily armored and deadly Roman legionaries rushing to board. That the corvus was the predominant means of combat for the Romans is attested by the Carthaginian losses, a large majority of which were captured, rather than sunk.

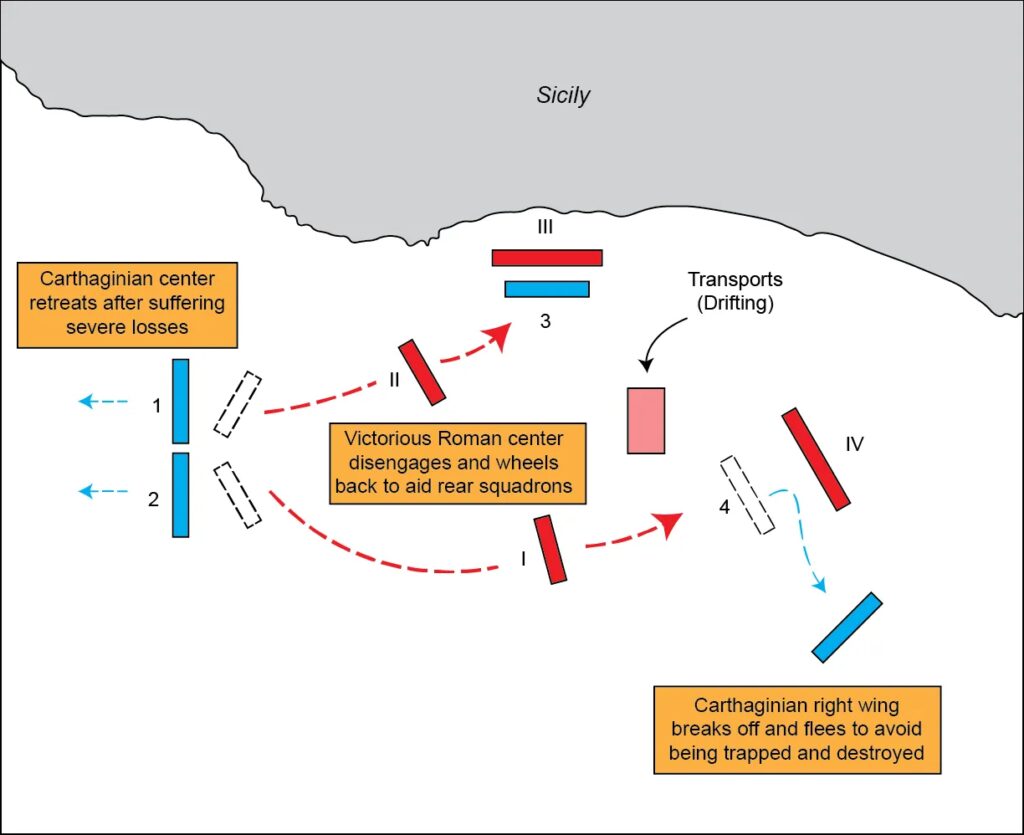

By the mid-afternoon, the remaining crews and captains of the Carthaginian center had had enough, and began to break off and retreat. Rather than pursue further, the Roman center, consuls still firmly in command, broke off and immediately began to wheel back to assist their rear squadrons. While the Carthaginian wings had acquitted themselves well, there was now nothing to be done with the squadrons of the Roman center bearing down on them, save extract themselves from the fight as fast as possible and make a break for it. Most of the Carthaginian right wing, which had open ocean on its flank, was able to escape, but the left wing was trapped near the shore and largely destroyed.

Cape Ecnomius had been a resounding victory for the Roman Navy. Intercepted with their transports in tow by a colossal Carthaginian fleet equal in size to their own, Roman captains and crews alike handled themselves with great cool and professionalism, foiling a well conceived Carthaginian battle plan. Total Roman losses amounted to just 24 ships and some 10,000 men – less than a quarter of Carthage’s losses, which ran to nearly 100 ships and more than 30,000 men.

On the whole, the Carthaginians seemed surprised at the greatly improved seamanship of the Romans. Earlier battles had seen the Romans handle their ships clumsily and unprofessionally, scraping out victories with the brute power of the corvus and the Roman infantry. In contrast, at Cape Ecnomius, the Roman fleet maneuvered well, as seen in the rapid run by the 3rd squadron to the shore where it could defend itself, though the weight and awkwardness of the corvus continued to give the Carthaginians an advantage in agility.

More broadly, Cape Ecnomius illustrates the tradeoff between scale and experience in warfare. Carthage began the war with a highly professional navy informed by a centuries old naval tradition, and in early engagements there was no question that their seamanship and maneuverability were vastly superior to the Romans. After the Battle of Mylae, however, both navies began to rapidly expand with aggressive shipbuilding programs, floating hundreds of new quinqueremes. This expansion forced Carthage to recruit tens of thousands of new rowers, just the same as the Romans. While the core of the Carthaginian navy still included many experienced crews and captains, this talent pool was diluted by the expansion of the navy, and by the time the great battle was fought at Cape Ecnomius, the Carthaginians were counting on a large number of essentially rookie crews who did not have the same edge that they had enjoyed in previous battles.

Ecnomius was a great Roman victory, and a sort of coming out party for the ascendant Roman Navy. It was also, incidentally, the swan song (or crow song, if you prefer) of the corvus. This had proven to be a formidable weapons system that was decisive in Rome’s early victories at sea, but it soon became apparent that the tradeoff in the seaworthiness of the ships was not worth the tactical advantage in the long run.

Despite smashing the Carthaginian fleet, the larger Roman assault on North Africa turned into a debacle. After pausing to rest and refit in Sicily, the Roman armada proceeded to Africa and landed a force of some 16,000 men on the coast. A series of Roman victories in the hinterland around Carthage spooked the Carthaginians into suing for peace, but the Roman consul in command – Marcus Atilius Regulus – demanded such excessively punitive terms that they resolved to continue fighting instead. The Carthaginians then hired a mercenary Spartan general named Xanthippus, who defeated the Romans at the Battle of Tunis and wiped out most of their expeditionary army.

The battle at Tunis was a harbinger of things to come, for the Romans. All of the previous engagements on land had taken place on Sicily, which is – to put it mildly – very poor cavalry country. Having previously only fought the Carthaginians in the Sicilian hills, the Romans had never before gotten a good look at the excellent Carthaginian cavalry, which were a mainstay of their land forces and would later be a critical arm in the great Hannibal’s many victories. Well, at Tunis the Romans got a look at the Carthaginian horse, and they didn’t like it much at all. Of the 16,000 men who had landed in Africa, barely 2,000 survived to be evacuated by sea.

That is a lot of action, but what was the score? The Roman Navy had acquitted itself remarkably well, utilizing the corvus to even the odds with the more experienced Carthaginians and winning a massive pitched battle at Ecnomius, but the larger expedition had gone all wrong, undone first by Regulus’s overly punitive peace conditions, secondly by the arrival of the Spartan general Xanthippus, and finally by the deadly Carthaginian cavalry. Limping home to lick its wounds, the Roman force suffered one final disaster. Off the coast of Sicily, a massive storm blew in which wrecked most of the fleet. After launching more than 300 ships in 256, only 80 survived to return to Italy the following year.

It seems, tragically, that the corvus was to blame. The weight of the apparatus is understood to have been destabilizing, making Roman ships less reliably seaworthy than their adversaries. They could still be handled well enough in favorable water, but evidently the corvus turned into a tremendous liability in a storm, overweighting the bow. Despite the great success of the corvus in battle, its use is never again mentioned after the great shipwrecking storm of 255. This is a powerful reminder of the pivotal role that the weather and the water play in naval operations. The corvus may have been deadly to Carthaginian ships that strayed within its reach, but it was powerless against Poseidon’s wrath.

Naval Attrition and State Capacity

The great campaigns of 256 and 255 brought Carthage and Rome to an impasse. Both had lost enormous fleets – Carthage to the Romans, and the Romans to the storm – representing a tremendous financial investment and tens of thousands of personnel. These costs seem to have sobered both belligerents, and there was an interim period of years where pitched battles were rare, fleet strength was slowly rebuilt, and the conflict turned into a gridlocked series of sieges, blockades, and interdiction efforts.

By 249, however, Rome had steadily rebuilt its fleet, and one of the year’s consuls, Publius Claudius Pulcher, hatched an ambitious plan. Frustrated by the long and protracted sieges and blockades of Carthage’s coastal strongholds in Sicily, Claudius decided to launch a surprise attack on the main Carthaginian naval base at Drepana (modern day Trapani, on the western tip of Sicily).

The plan had a certain bold logic to it. The personnel of Claudius’s fleet had been steadily attrited by their participation in a long and bloody siege at Libyaeum – a fact that the Carthaginians were certainly aware of. What the Carthaginians did not know, however, was that Claudius had just been reinforced by 10,000 fresh rowers, who had been dropped off in eastern Sicily and then marched overland to join his fleet. Claudius therefore deduced that the Carthaginians likely did not have an accurate estimate of his strength. His plan was to row by night from Libyaeum to Drepana, some 50 kilometers up the coast, to catch the Carthaginians by surprise, ambushing and trapping their fleet while it was still in the harbor.

In an ominous moment for pious Romans, however, Claudius began the operation with an act of impetuous blasphemy. The Romans were always meticulous about consulting omens before battle. In this case, however, the sacred chickens refused to eat – a strong sign that the battle was not sanctioned by the gods. Claudius allegedly became so angry that he grabbed the chickens and threw them overboard into the sea, shouting “if they will not eat, let them drink.” He should have listened to the chickens.

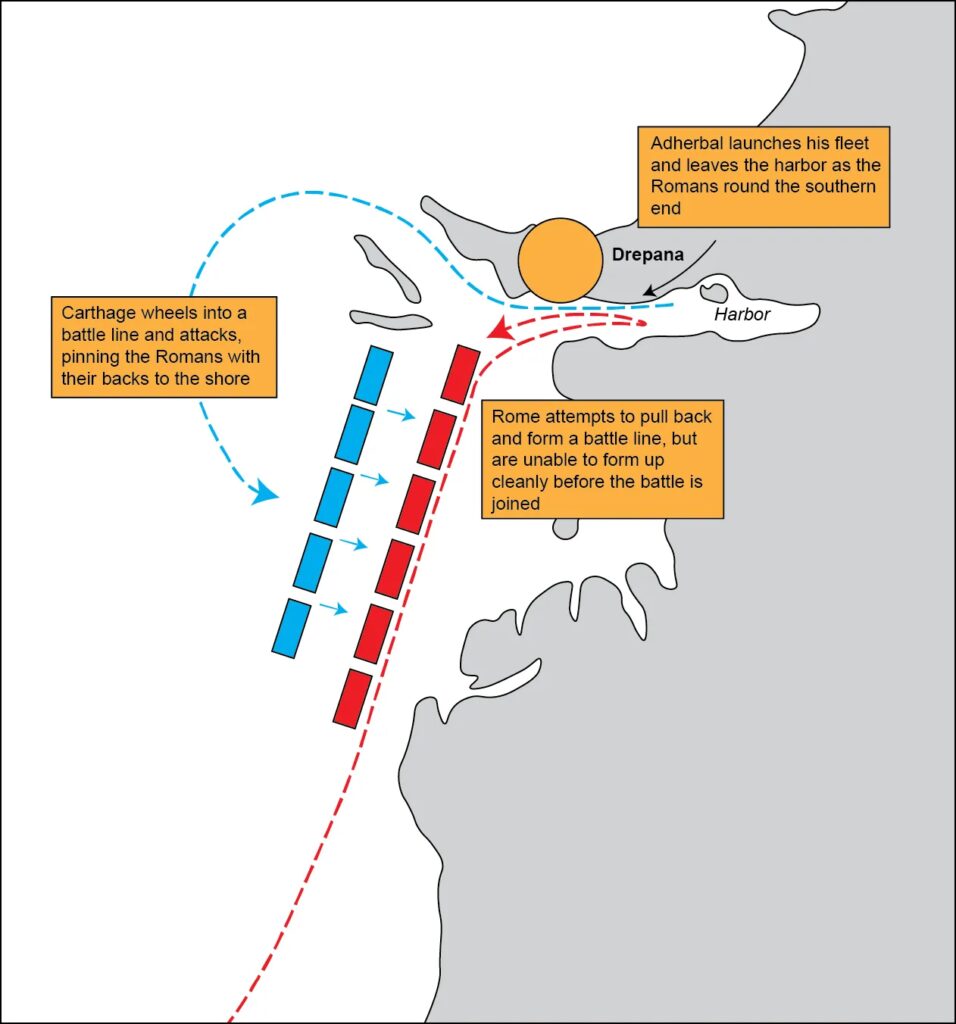

If the plan had worked, it might have ended the war. Unfortunately for Claudius and his men, Drepana became a painful example of the difference that a few minutes can make. The Roman armada – some 120 ships in all – set out at night, but their voyage was slow due to the inexperience of Claudius’s new rowers and the difficulty of keeping ships on station at night. It was not so much that they could get lost – after all, the route simply followed the coast northward – but the fleet straggled and became disorderly, with Claudius’s own flagship falling into the rear of the column. Then, in the early morning, they were spotted by Carthaginian reconnaissance on land, and messengers raced to warn Adherbal, the Carthaginian admiral at Drepana.

Adherbal understood that if his fleet was caught still at harbor, it would be trapped and easily blockaded. He raced to mobilize his crews to their ships and loaded up as many marines as he could scrounge up, and immediately put to sea.

Drepana was decided by the narrowest of margins. Adherbal’s flagship rowed out the mouth of the harbor exactly as the first Roman ships rounded the corner – an almost literal example of ships passing in the night (except it was mid-morning). Claudius had missed his chance by less than an hour. The Carthaginian fleet was now beginning to sweep out to see in a wide arc, turning back towards the Roman armada crawling along the shore. Claudius attempted to form his ships into a battle line to meet them, but was stymied first by the fact that his fleet had become disorderly and strung out during the night voyage, and secondly by the fact that his lead vessels were already rowing into the Drepana harbor. In their attempt to quickly turn back and form up for battle, many of the leading Roman ships in the harbor collided with each other and sheared their own oars.

The Romans did manage to form an improvised battle line, but it was tired from a night of rowing, disorganized, and – most importantly – arranged with its back to the coast. While in the past this had been a benefit, as it allowed the Roman ships to protect their sterns while facing outward with the corvus, by this time the corvus had been abandoned. The battle therefore took the form of conventional boarding and ramming actions, and the presence of the shore at the rear put the Romans at a distinct disadvantage. With their backs at the open sea, the Carthaginians were able to freely reverse away from danger, while the Romans were trapped against the shore and had little room to maneuver. If a Carthaginian ship found itself in trouble, it could simply back away; a Roman ship could not. The battle – originally envisioned as an ambush of the Carthaginians in port – turned into a disaster for the Romans, who lost 75% of the fleet. Claudius, who managed to break out and escape with a mere 30 ships, was so widely panned for the debacle that he was eventually charged by the senate with treason. The sacred chickens, who might have testified to his rashness, were unavailable for comment.

After Drepana, the Carthaginians regained naval supremacy for a time and had a strategic window of opportunity. The expense of having to continually build and rebuild massive fleets was extremely burdensome, even for a society as wealthy and extractive as Rome. The loss of yet another armada to a massive storm late in 249 practically eradicated what remained of the Roman fleet, and the Senate opted to temporarily suspend naval construction and reprioritize the land war in Sicily. Notably, however, Carthage opted not to push the envelope, and seems to have downsized their fleet, thinking perhaps that the Romans were exhausted and no doubt worried about their own mounting financial burdens.

It was not until 243, six years after the debacle at Drepana, that the Romans decided to build yet another fleet and push for a decisive outcome on the water. This time, they would get it. The state, however, was effectively bankrupt by this time, and the new fleet had to be financed with donations by the aristocracy, with wealthy Roman families “sponsoring” ships. On paper, this took the form of “loans” to the state, but the terms were interest free and were due to be repaid with the indemnity to be imposed on a defeated Carthage. They thus represented a genuine patriotic commitment by the Roman elite, and a sort of financial pledge of faith in Roman victory.

By 242, the Romans had once again floated a fleet of over 200 quinqueremes, and they immediately deployed them to the Sicilian coast to blockade the remaining Carthaginian strongholds there, including the naval base at Drepana. Unlike in prior campaigns, however, the purpose of these blockades seems to have been very explicitly to draw out the Carthaginian fleet for a decisive battle. The Roman admiral in command, one Caius Lutatius Catalus, made it a particular point to keep his rowers on a calibrated training routine and kept them well fed and rested, in anticipation of a showdown with the enemy fleet.

The Carthaginians were now in a very serious bind. The new Roman fleet (the sudden materialization of which must have come as a great shock) had successfully blockaded important ports, putting much of the Carthaginian land forces in danger of being starved out. The Carthaginian navy had to resupply them, but it also had to be prepared to fight an engagement with the Roman fleet. Resupplying the garrisons on land meant carrying grain and other supplies, which in turn reduced the space available for marines, which in turn gave the Carthaginians poor prospects in a naval battle. The solution, therefore, was a dangerous gambit, but the only one which offered to solve all of these problems. The mass of the Carthaginian fleet, some 250 ships in all, was to dash for the Sicilian coast laden with grain and supplies, avoiding the Roman fleet. The grain would then be offloaded, and infantry would be onboarded in its place, so that the fleet could seek a fight with the Roman navy and defeat it, hopefully for the last time.

The Carthaginians got a fair chance to execute their ambitious gambit. They crossed from Carthage to the westernmost of the Aegates Islands, some 35 kilometers off the western tip of Sicily. On March 10, 241, a strong easterly wind began to blow through the Aegates, offering the possibility that the Carthaginians could raise sails and make a swift dash to the Sicilian coast before the Romans could intercept them. Their admiral, Hanno, decided to make a run for it. Catalus, however, was alert to their presence. He now faced a difficult choice of their own. He had an opportunity to intercept Hanno’s fleet while it was still burdened with supplies and low on marines, but to do so he would need to row into the wind. The war now hinged, in essence, on a race.

Hanno’s ships were bearing down on Sicily at top speed, but it was not fast enough. Catalus’s crews coped admirably with the unfavorable wind and formed up a battle line in the path of the oncoming Carthaginians, who now had no choice but to fight. The ensuing battle was something of a foregone conclusion. The numbers in the fleets were roughly equivalent – somewhere between 200 and 250 ships on both sides – but the Romans were far better configured for the fight. The Carthaginian ships were much heavier and less maneuverable, both because they were burdened with supplies and because they had their masts. Masts and sails granted extra speed when sailing in a straight line with the wind, but in battle they merely became dead weight that burdened the ships. Catalus, in contrast, had removed his ships’ masts beforehand to maximize his agility in battle. Furthermore, the Carthaginian ships were loaded with supplies, not marines, while the Romans carried full complements of fighting men. Being thus undermanned and overweight, the Carthaginian fleet had poor prospects from the outset and was smashed. Nearly 120 Carthaginian ships were lost, against a mere 30 Roman vessels.

Catalus’s interception and defeat of the Carthaginians off the Aegates Islands proved to be the final, deciding victory of the war. Rome had now regained naval supremacy, and Carthage was financially unable to construct yet another fleet. Furthermore, the defeat of Hanno’s mission to Sicily meant that the Romans now had a firm blockade in place, which isolated and threatened to completely starve out the remaining Carthaginian forces on the island. Defeated at sea and cut off from their Sicilian bases, the Carthaginians resigned themselves to defeat and sued for peace.

With Carthaginian surrender in 241, the Romans became the de-facto masters of the western Mediterranean sea. Of the terms imposed on Carthage, by far the most important was the abandonment of their bases and possessions in Sicily. The short range of galley fleets made them heavily dependent on forward bases and ports to operate at distance – therefore, even if Carthage decided to build a new fleet in the future, its ability to contest the sea would have been sterilized by the loss of the Sicilian bases. In contrast, the Romans now had full control over Sicily, which allowed their navy to operate across the entire theater.

This is why, when Carthage and Rome renewed their multi-generational struggle in 218 with the beginning of the Second Punic War, Carthage conducted no meaningful naval operations at all. The operational centerpiece of this war was the great Hannibal’s famous overland invasion of Italy, but this overland strategy (and the famous crossing of the alps) was made necessary by Rome’s control of the waves. Unable to operate at any scale or distance in the western Mediterranean, Hannibal instead had to accumulate forces in Carthage’s Iberian territories and laboriously march them to Italy.

How did Rome defeat Carthage, despite the latter’s superior naval pedigree and early advantages in the naval theater? According to Polybius (who, although Greek himself, was an unequivocally pro-Roman author with no incentive to lie) the Romans lost a total of some 700 warships in the First Punic War, against roughly 500 Carthaginian losses. Many of these Roman losses were due to storms, to be sure, but the fact remained that the Roman navy did suffer roughly 40% more losses than its adversary. It does not much matter to a drowned sailor whether the enemy or the weather has killed him.