American military supremacy is an article of faith for most Americans, granting the military a strong measure of resistance to the broad decay in the trust that people have in their public institutions. Congress, the president, courts, banks, and tech companies are all lousy and crooked in the eyes of most Americans, but the military, almost uniquely, retains the trust and support of the majority. The prevailing view remains that the American military is the best trained, most technologically advanced, most competently lead, and liberally equipped force in the world. America’s colossal defense budget is practically a point of pride.

America is, to be sure, one of the great martial nations of world history. It has generally won conventional conflicts, and won them big. It retains world leading capabilities in many domains, enormous power projection, and it produces exceptional fighting men. Where Americans go wrong, however, is taking this excellence to be a law of nature. An army is not a tiger, dictated by biology to be the largest, fastest, and most powerful predator in the world. It is, rather, an institution which evolves and learns over time, developing particular patterns of war-making which may or may not be well calibrated for particular operating environments.

In the latter half of the 20th Century, during that peculiar security condition that we call the Cold War, the United States Army underwent a roller coaster of institutional change – rapidly demobilizing after the defeat of Germany, coming aghast at its own unpreparedness in Korea, and cannibalizing itself in Vietnam. By 1970, the US Army was in a state of clear crisis, with its own senior leadership increasingly concerned about their ability to win a high intensity land war. From this crisis, however, the American land force began a climb back to the apex, with a radically revamped operational doctrine, new weapons programs, and an invigorated commitment to fighting an American brand of maneuver warfare.

The Menace: Stalin in Manchuria

The Second World War had a strange sort of symmetry to it, in that it ended much the way it began: namely, with a well-drilled, technically advanced and operationally ambitious army slicing apart an overmatched foe. The beginning of the war, of course, was Germany’s rapid annihilation of Poland, which rewrote the book on mechanized operations. The end of the war – or at least, the last major land campaign of the war – was the Soviet Union’s equally totalizing and rapid conquest of Manchuria in August 1945.

Manchuria was one of the many forgotten fronts of the war, despite being among the oldest. The Japanese had been kicking around in Manchuria since 1931, consolidating a pseudo-colony and puppet state ostensibly called Manchukuo, which served as a launching pad for more than a decade of Japanese incursions and operations in China. For a brief period, the Asian land front had been a major pivot of world affairs, with the Japanese and the Red Army fighting a series of skirmishes along the Siberian-Manchurian border, and Japan’s enormously violent 1937 invasion of China serving as the harbinger of global war. But events had pulled attention and resources in other directions, and in particular the events of 1941, with the outbreak of the cataclysmic Nazi-Soviet War and the Great Pacific War. After a few years as a major geopolitical pivot, Manchuria was relegated to the background and became a lonely, forgotten front of the Japanese Empire.

Until 1945, that is. Among the many topics discussed at the Yalta Conference in the February of that year was the Soviet Union’s long-delayed entry into the war against Japan, opening an overland front against Japan’s mainland colonies. Although it seems relatively obvious that Japanese defeat was inevitable, given the relentless American advance through the Pacific and the onset of regular strategic bombing of the Japanese home islands, there were concrete reasons why Soviet entry into the war was necessary to hasten Japanese surrender.

More specifically, the Japanese continued to harbor hopes late into the war that the Soviet Union would choose to act as a mediator between Japan and the United States, negotiating a conditional end to war that fell short of total Japanese surrender. Soviet entry into the war against Japan would dash these hopes, and overrunning Japanese colonies in Asia would emphasize to Tokyo that they had nothing left to fight for. Against this backdrop, the Soviet Union spent the summer of 1945 preparing for one final operation, to smash the Japanese in Manchuria.

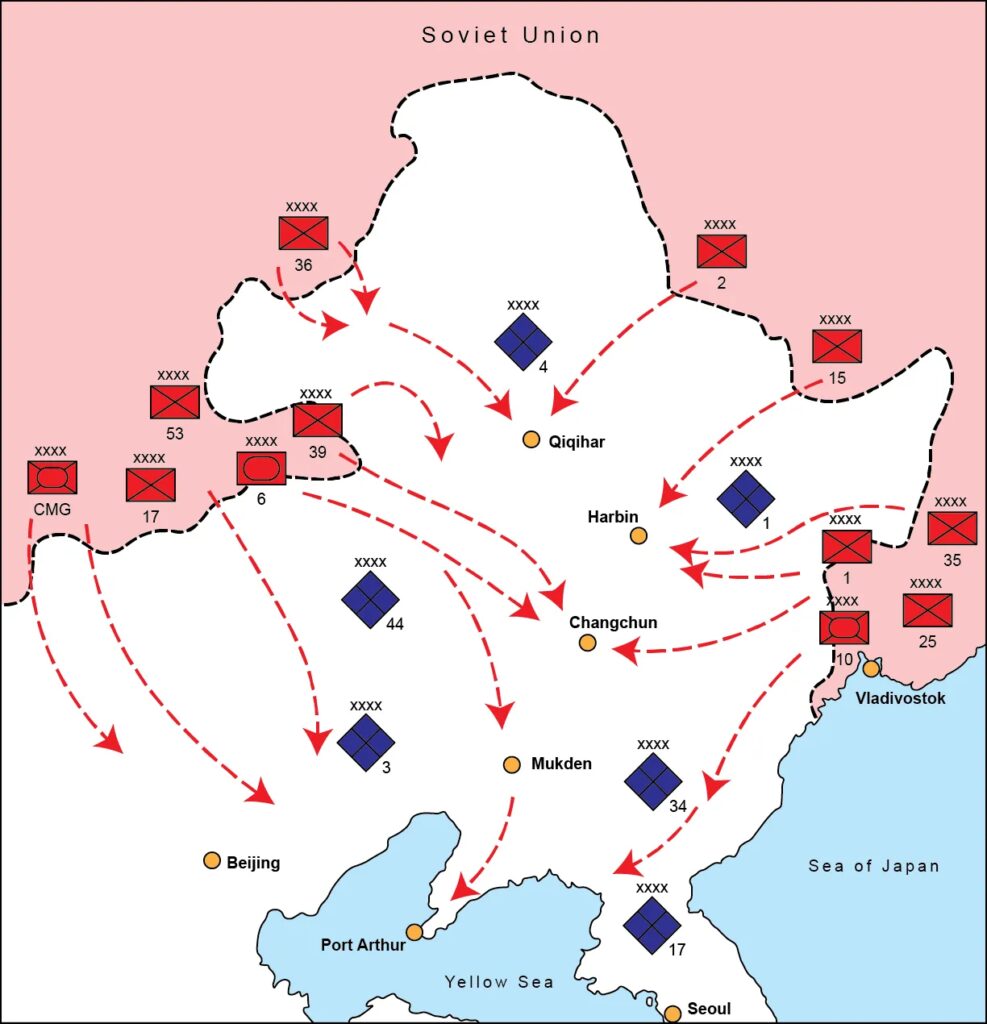

The Soviet maneuver scheme was tightly choreographed and well conceived – representing in many ways a sort of encore, perfected demonstration of the operational art that had been developed and practiced at such a high cost in Europe. Taking advantage of the fact that Manchuria already represented a sort of salient – bulging as it did into the Soviet Union’s borders – the plan of attack called for a series of rapid, motorized thrusts towards a series of rail and transportation hubs in the Japanese rear (from north to south, these were Qiqihar, Harbin, Changchun, and Mukden).

By rapidly bypassing the main Japanese field armies and converging on transit hubs in the rear, the Red Army would effectively isolate all the Japanese armies both from each other and from their lines of communication to the rear, effectively slicing Manchuria into a host of separated pockets.

There were, of course, a host of reasons why the Japanese had no hope of resisting this onslaught. In material terms, the overmatch was laughable. The Soviet force was lavishly equipped and bursting with manpower and equipment – three fronts totaling more than 1.5 million men, 5,000 armored vehicles, and tens of thousands of artillery pieces and rocket launchers.

The Japanese (including Manchurian proxy forces) had a paper strength of perhaps 900,000 men, but the vast majority of this force was unfit for combat. Virtually all of the Japanese army’s veteran units and equipment had been steadily transferred to the Pacific in a cannibalizing trickle – a vain attempt to slow the American onslaught. Accordingly, by 1945 the Japanese Kwantung Army had been reduced to a lightly armed and poorly trained conscript force that was suitable only for police actions and counterinsurgency against Chinese partisans.Really, there was nothing for the Japanese to do. The Kwantung Army had far less of a fighting chance in 1945 than the Wehrmacht had in the spring of that year, and everyone knows how that turned out. Unsurprisingly, then, the Soviets broke through everywhere at will when they began the assault on August 9. Soviet armored forces found it trivially easy to overrun Japanese positions (armed primarily with archaic, low caliber antitank weaponry that could not penetrate Soviet armor even at point blank range), and by the end of the first day the Soviet pincers were driving far into the rear.

It is easy, in hindsight, to write off the Manchuria campaign as something of a farce: a highly experienced, richly equipped Red Army overrunning and abusing an overmatched and threadbare Japanese force. In many ways, this is an accurate assessment. However, what the offensive demonstrated was the Red Army’s extreme proficiency at organizing enormous operations and moving at high speeds. By August 20 (after only 11 days), the Red Army had reached the Korean border and captured all their objectives in the Japanese rear, in effect completely overrunning a theater that was even larger than France. Many of the Soviet spearheads had driven more than three hundred miles in a little over a week.

To be sure, the combat aspects of the operation were farcical, given the totalizing level of Soviet overmatch. Red Army losses were something like 10,000 men – a trivial number for an operation of this scale. What was genuinely impressive – and terrifying to alert observers – was the Red Army’s clear demonstration of its capacity to organize operations that were colossal in scale, both in the size of the forces and the distances covered.

More to the point, the Japanese had no prospect of stopping this colossal steel tidal wave, but who did? All the great armies of the world had been bankrupted and shattered by the great filter of the World Wars – the French, the Germans, the British, the Japanese, all gone, all dying. Only the US Army had any prospect of resisting this great red tidal wave, and that force was on the verge of a rapid demobilization following the surrender of Japan. The enormous scale and operational proclivities of the Red Army thus presented the world with an entirely new sort of geostrategic threat.

Soviet forces would begin a formal withdrawal from Manchuria and Korea in 1946, but as they receded they left in their wake consolidated and well supported communist political machines, including the Workers Party of Korea under Chairman Kim Il Sung, and the Communist Party of China under Chairman Mao Zedong. In this regard, Communism showed itself to be a much more geopolitically agile and adaptable ideology than Nazism or Japanese imperialism, as it preached a millenarian, transnational, and ostensibly scientific ideology that could motivate indigenous political parties, and the Soviet government had already developed tried and true institutional mechanisms for mobilizing resources and maintaining a political monopoly. In other words, while Nazism had always clearly been for the Germans and the Germans alone, communism could recruit and galvanize local believers around the world, and the Soviet model could give them the tools to take and hold power.

Thus, the Soviet Union presented something of a unique geopolitical triple threat. It had astonishing state capacity in its own right, in its ability to field huge armies and roll them over continent sized spaces; it had ideological penetration and appeal stemming from Communism’s universalizing claims and an attractive message of social justice and scientifically ordered abundance; and it had a proven model of effective political institutions which could allow local communist parties to establish powerful political monopolies. Add it all together and you get the great menace of the Cold War: a vast and powerful Red Army that could roll over its enemies with ease, recruit enthusiastic cadres of local communists, and establish durable state structures.

All of these powers had been on full display in Asia, with the lightning advance, the rapid consolidation and funneling of resources to local communist parties, and the durable North Korean and Chinese party-states that were left behind once the Red Army withdrew. To make matters even worse, this powerful Soviet expansion apparatus was now precariously forward deployed deep in the heart of Europe, with the Soviet frontier pushing all the way into Central Germany.

The fear that the Soviet Union would replicate its Manchurian exploits in Europe became the foundational anxiety of the Cold War – predating both Soviet atomic weapons and, by extension, the fear of nuclear war. As early as 1947, France and the United Kingdom began signing joint defense pacts, which expanded to include Belgium and the Netherlands with the 1948 Treaty of Brussels, bringing about the short-lived “Western Union Defense Organization” (WUDO). It was clear, however, that such a limited alliance structure would be utterly inadequate in the event of war with the Soviet Union. France and Britain were degraded, threadbare powers in no place to fight yet another major war. One telegram sent from Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery’s staff at WUDO headquarters to a liaison at the American State Department simply said:

Present instructions are to hold the line of the Rhine. Presently available forces might enable me to hold the tip of the Brittany Peninsula for three days. Please advise. Montgomery himself, though, said it best. Asked what it would take for the Red Army to break through to the Atlantic, he simply answered:

Shoes.Thinking about the Unthinkable

The transition from the end of the Second World War to the beginning of that peculiar global security dilemma which we call the Cold War is often poorly understood or even glossed over – obviously, the entire history of the late 1940’s is beyond the purview of our interest in the history of maneuver doctrine and operations, but a skeletal recollection may still be useful.

The beginning of the Cold War, as such, can probably be best identified as a sequence of events in 1948 and 1949, which together represented the breakdown of the post-war Soviet-American cooperation in Europe and the consolidation of the power blocs that would characterize the Cold War. In those intervening years after the end of the Second World War, the United States and the Soviet Union undertook a series of actions designed to consolidate their positions in Europe according to the postwar settlement.

These actions took the form of both direct influence and attempts to exclude the other party from the appropriate sphere. The United States, for example, rehabilitated and integrated Western European economies under the Marshall plan while the USSR forbade eastern bloc countries from participating, fearing American economic and political penetration into its satellites. While the USSR reconstituted governments in Eastern Europe into Soviet style communist political monopolies, communists were ejected from governments in France and Italy. There was thus a certain degree of symmetry as both the USSR and the United States consolidated the two spheres of Europe, creating a sharp split down the spine of the continent.

The situation continued to spiral, with the United States intervening in Greece in 1947 to prevent a communist takeover, a 1948 Soviet-backed coup by communists in Czechoslovakia, and the subsequent Soviet abandonment of the Allied Control Council (in effect ending the primary post-war joint body for administration in occupied Germany). The culminating point of all this was an attempted communist putsch in Berlin, followed by the infamous Soviet blockade of the German capital and the Berlin airlift in the winter of 1948. It is not a coincidence that the formation of NATO on April 4 coincided with the closing weeks of the Berlin blockade and the collapse of the Allied Control Council. The formation of a formal American military bloc in Western Europe was the natural culmination of a security situation that had deteriorated with alarming speed. The Soviet Union predictably followed with the Warsaw Pact a few years later. The Cold War was on.

What matters most for our purposes, of course, is not this whirlwind sequence of events or even the breakneck bifurcation of postwar Europe into Soviet and American spheres. What is interesting to us is the fact that the onset of the Cold War presented the United States with a novel problem, namely how to plan for and think about a future war on the European Continent against the Soviet-led forces of the Warsaw Pact. This was, in fact, a very new position for the United States, which for most of its existence had maintained a relatively skeletal officer corps that did not think deeply about operations, or military doctrines at all.

The American Army had always been most unlike its European counterparts, spending most of its life as a border constabulary in the expanding American West. It was certainly nothing like, say, the Prusso-German Officer Corps, which was accustomed over the decades to theorizing, debating, planning, and simulating ad nauseum. While all the major continental armies spent the 1930’s thinking deeply about armored warfare and doctrinal concepts, the US Army had no armored force at all, and the simple field regulations issued to officers had nothing to say about the matter. It was not until 1941 (after the German campaigns in Poland, France, and the invasion of the Soviet Union) that the US Army conducted its first ever operations scaled mechanized field maneuvers.

The difference between the pre and post World War Two American security dispositions could not have been more stark, therefore. While the pre-war army thought very little about continental warfare in a systemic or doctrinal way, the US Army in the Cold War was frequently preoccupied with theorizing about a future European war against the Soviet bloc. While prewar America was secure in its latent industrial power and the strategic depth provided by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, postwar America remained forward deployed in both hemispheres. Central European lands that had once been the stomping ground of Prussian and French armies now became an American security fixation.

Matters were further complicated by the entirely novel kinetic additive of atomic weapons, which gave frightening new capabilities and an uncertain use case. Throughout the cold war, both the USSR and the USA would be constantly assessing and reassessing both theirs and the other’s willingness to use nuclear weaponry, and this in turn fed assumptions about how a ground war in Europe would be fought.

America’s atomic monopoly did not last very long in absolute terms, but it nevertheless shaped the base of Cold War military thinking. In the years leading up to the Soviet Union’s first successful atomic test in 1949, there were many assumptions made about the security that the west could derive from the American nuclear monopoly (including, most fantastically, Bertrand Russell’s call for a preemptive nuclear attack on the Soviet Union). All of these assumptions were shattered by the speed at which the USSR was able to demonstrate its own atomic powers.

Paradoxically, however, the Soviet Union’s 1949 atomic test did not ameliorate Soviet insecurities in the short term. This was because, although the test was an important milestone and show of force, the USSR was not able to immediately convert the test into use-ready atomic weaponry. In fact, the Soviet Air Force did not take delivery of operational atomic bombs until 1954. This meant nearly a full decade of acute atomic vulnerability which strongly shaped Soviet strategic sensibilities.

The upshot of all this was that America’s atomic monopoly lasted much shorter than the United States had originally hoped and anticipated, but much too long for Moscow’s comfort. The security of the early atomic monopoly allowed the United States to rapidly demobilize its armies; simultaneously, the Soviet Union hoped to lean on vastly superior conventional forces as a counterposition to the American nuclear arsenal, and those same gargantuan conventional forces deepened the sense of crippling insecurity in Western Europe.

As previously mentioned, by the late 1940’s it was already clear that the limited WUDO alliance (comprised essentially of France, Britain, and the Low Countries) was simply too weak to present a credible opponent to the Soviet Union and the emerging Eastern Bloc. This sense of European insecurity only intensified between 1949 and 1951, with the successful Soviet atomic test, the victory of the communists in China, and the war in Korea. Any earnest attempt to contend with the Red Army would inevitably require the involvement of the United States.

Even with American involvement in European security via NATO (formed in 1949), there were a host of difficult and divisive issues to parse out. In contrast to the Russian perception of NATO as nothing but a tool of American foreign policy, the alliance’s early history was wracked with disagreements about how to ensure European security. First and foremost was the question of Germany’s role in Europe.

It was quite clear to many, particularly in America, that any credible European alliance would require the rehabilitation and integration of West Germany (formally the Federal Republic of Germany), which was formed in 1949 through the merging of the British and American occupation zones. Even after the trauma of the Second World War and the division of the country, West Germany was by far the most populous and potentially powerful country in Western Europe. It was also, rather obviously, likely to be the critical battleground in any future war with the Soviet Union. Therefore, the Anglo-Americans decided early on that the rehabilitation and rearmament of West Germany was critical for European security. This plan ran into vehement opposition from the French, who remained deeply resentful towards Germany and suspicious of any attempt to rearm them – one particularly bold French proposal even called for German infantry to be inducted into the European commands (in effect, preventing the West Germans from having any organic units higher than a battalion and subordinating them to French divisions).

In the end, it was clear that German manpower and resources would have to be fully leveraged, particularly in light of NATO’s preliminary goals of fielding a 50 division army in Western Europe. Therefore, as a sop to the French, the unification and rearmament of Germany was counterweighted by additional American deployments in Europe, as a gesture of America’s commitment to European defense and a guarantee that France would not soon find itself dominated once again by the Germans. The integrated NATO military command and preponderance of American influence ensured that German resources could be mobilized without granting West Germany any genuine strategic autonomy. Thus, the basic strategic arrangement of European security was established by the early 1950’s, with the first General Secretary of NATO, Lord Hastings Ismay, famously observing that NATO had been structured to “keep the Americans in, the Russians out, and the Germans down.” Notably, however, the item about “keeping the Americans in” was viewed not as an American attempt to maintain influence in Europe, but the other way around: Europeans feared being abandoned by the Americans and wanted to ensure an American commitment to European security.

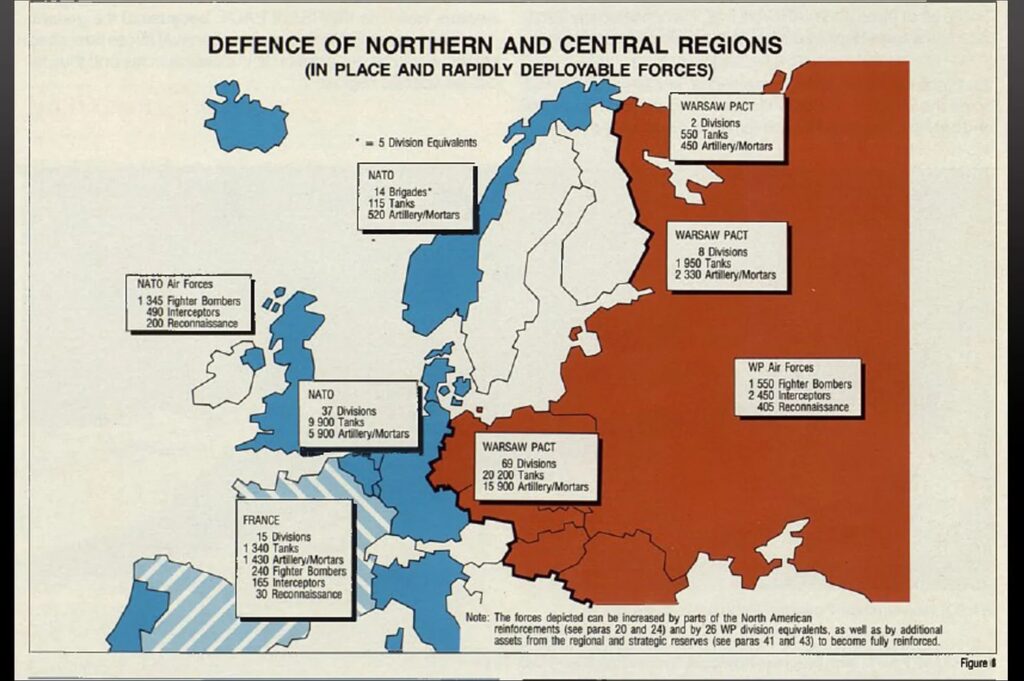

Even with all of this diplomatic and geostrategic horse trading, however, the math of force generation was simply not in NATO’s favor. Even with plans to raise 12 German divisions, it was clear that NATO’s 1952 decision to field a 50 division force was simply unrealistic – particularly because western leadership was loathe to risk the fragile economic recovery of Western Europe by adopting a crash rearmament program. This was plainly evident to Dwight Eisenhower, with his intimate knowledge of the European theater, and when he became president in 1953 his national security team immediately began to implement a new defense posture that aimed to use atomic weaponry as a substitute for conventional ground forces in Europe.

In the mid 1950’s, therefore, NATO’s war planning (really, America’s) was built around a 30-division ground force which would be tasked with delaying and funneling Soviet forces into concentrated masses which would offer enticing targets for tactical (battlefield) atomic weapons, paired with a policy of so-called “massive retaliation”, which promised catastrophic atomic bombing of Soviet rear areas and cities. Eisenhower’s Secretary of State, John Foster Dulles, said in a public 1954 speech:

We need allies and collective security. Our purpose is to make these relations more effective, less costly. This can be done by placing more reliance on deterrent power and less dependence on local defensive power... Local defense will always be important. But there is no local defense which alone will contain the mighty land power of the Communist world. Local defenses must be reinforced by the further deterrent of massive retaliatory power.Perhaps at this point an editorial comment is warranted. Our focus in this (very long) series of articles has been the history of maneuver in warfare. It would seem warranted to ask whether we’ve lost the plot here, with a very long digression into the early history of NATO and America’s nuclear use doctrine. This is fair enough. What we wish to establish, however, is that during the first decades of the Cold War American operational sensibilities were heavily predicated on the inevitability of atomic use, the application of atomic weaponry as a deterrent, and the battlefield uses of atomic weapons.

Almost no thought was given to winning a conventional war against the USSR. Louis A Johnson, Secretary of Defense from 1949-1950, was frank in his belief that America had practically no need for non-nuclear forces, and openly mused that the Navy and the Marine Corps out to be abolished outright. In such an environment, little thought was given to conventional operations. By the end of the 1940’s, General Omar Bradley was of the opinion that the US Army “could not fight its way out of a paper bag.”

This thinking was soon mirrored by the Soviets themselves, particularly with Nikita Kruschchev’s 1960 address to the Supreme Soviet in which he proclaimed a new strategy of comprehensive nuclear missile warfare. Under such a framework, there was virtually no distinction between attack and defense – any conventional conflict with the west would be implicitly presumed to go nuclear, therefore the only way to fight such a war was to immediately launch an all-out ground offensive paired with nuclear annihilatory strike. As a 1960 Soviet handbook put it:

Soviet military doctrine sees concerted offensive operations as the only acceptable form of strategic actions in nuclear warfare, and stresses that strategic defense contradicts our view of the character of a future nuclear war and of the present state of the Soviet armed forces… Under modern conditions, passivity at the outset of a war is out of the question, for that would be synonymous with annihilation.Throughout the 1960’s, therefore, the Soviet Union conducted an enormous armaments program which expanded not only their own conventional and nuclear forces, but also the forces of Warsaw Pact satellites, which received over 1,200 new aircraft, 6,000 tanks, and 17,000 armored equipment in the first half of the decade. There was particular emphasis on the base of fire, with Soviet divisions expanding from 8,000 to 12,000 men to increase the size of the organic divisional artillery, and a host of new rocket brigades being provisioned for Warsaw Pact armies.

The culmination of the Soviet “60’s program”, if we can call it that, was the 1969 Zapad-69. The Red Army simulated a nominal “attack” by NATO, and responded with an all-out offensive by five different army groups, which went punching into West Germany, shooting over the Rhine, south towards the Swiss border, and northward into Denmark. Given the enormous preponderance of Eastern Bloc force generation, Soviet planners concluded (probably realistically) that by the fourth day of the war their spearheads would be well established on the Rhine, and NATO would resort to atomic weapons to avoid total defeat. At that point, the conventional phase of the war would be over and a full nuclear exchange would be underway.

All that is to say, that although both the USSR and the USA followed their own unique paths of strategic development, by the 1960’s had come to the assumption that conventional war would lead necessarily to nuclear war. A host of different doctrinal names, like Eisenhower’s “massive retaliation” and Khrushchev’s “comprehensive nuclear missile warfare” all related essentially to the primacy of nuclear warfare and the growing centrality of escalation management and game theory.

In such an operating environment, there was little role for dynamic thinking about how to fight a conventional war in Europe, particularly for the US Army. Eisenhower rather explicitly viewed US ground forces as little more than a trip wire and a delaying screen that would set the stage for decisive action from the US Strategic Air demand.

Ground forces became so subordinate that the US Army Chief of Staff, General Maxwell Taylor, contrived an entirely new structure for US Army Divisions that would allow them to have organic nuclear weapons systems (an 8-inch howitzer battery equipped with atomic shells and the MGR-1 Honest John Atomic Rocket system). His rational was essentially the institutional survival of the army: nuclear war had become so fundamental to European war scenarios that Taylor believed the Army would have to carve out an atomic role for itself if it wanted to retain its budgetary and personnel access.

A conventional war of mobile operations, in the style of the Second World War, increasingly seemed like an anachronism. Mid-century American conflicts like Korea and Vietnam offered few glimpses into what a peer war in Europe would be like. Korea, after episodic periods of mobility, largely developed into a firepower intensive slugfest amid the mountainous and unfriendly terrain of the peninsula. Vietnam, of course, devolved into an infamous American military headache, but one which seemed to have few parallels to a future war in Europe. Between the focus on atomic weaponry and befuddling Asian misadventures, the world-beating US Army seemed adrift. Then the Israeli Defense Forces recieved a nasty surprise on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur.

Revival (in Theory)

The Vietnam War as a major socio-political stressor for mid-century America is a well worn and well understood story. Less well known, however, was the way that the war brought the American military establishment to a state that bordered on crisis. Beginning with Lyndon Johnson’s decision to fight Vietnam without mobilizing reserves or national guard (instead choosing to lean on the active force and the draft) caused the war to cannibalize and drain the active force. Meanwhile, the financial drain of the war ate away at the defense budget, to the effect that the army fielded no major new systems during the 1960’s. Finally, defeat was brushed aside as a manifestation of American political failures and the peculiar nature of fighting a tropic counterinsurgency – the broad conclusion seems to have been that the military did not fail in Vietnam so much as the parameters of the war had failed to accommodate the military.

As a result, the US Army entered the 1970’s with aging weapons systems, low institutional confidence, and no real lessons learned. It is not an exaggeration to say that the US Military (and the Army in particular) were at a sort of institutional nadir at this point. This happened to coincide, however, with a renewed interest in thinking about winning a conventional war in Europe, that is to say, without immediate recourse to atomic weaponry, largely due to the growth of Soviet second strike capabilities. In other words, the US Army had a sudden revival of interest in fighting a conventional ground war at exactly the time that it had the lowest capacity to due so.