Defence Secretary Ben Wallace reminded the Commons this week that, despite their territorial defeat, Islamic State remains the greatest terror threat to the United Kingdom by a long way. He added that some 360 members who joined the terrorist group in Iraq and Syria and returned to the UK are deemed ‘low risk.’

If this doesn’t inspire confidence, it shouldn’t. Some of the worst attacks in recent years have been conducted by people already on the security services’ radar.

Khalid Masood, the Westminster Bridge attacker, and Salman Abedi, responsible for the Manchester bombing were both known to security services before they struck. In fact, one of the 2017 London Bridge attackers’ extremism was so well known he appeared in a Channel 4 documentary. Forget ‘lone wolves’ — try known wolves.

This is not the fault of our overwhelmed security services. There is no secret formula for making an assessment on who poses a risk and when, and they have no choice but to de-prioritise some cases. But some of the de-prioritised will strike.

Besides, they aren’t the only ones making mistakes. Usman Khan was considered a poster boy for the Cambridge ‘Learning Together’ program, before going on a murder spree at Fishmonger’s Hall, London Bridge.

MI5 is aware of some 43,000 people who pose a threat. Among those are an unprecedented number of extremists in prison — many of whom are on their way out — and several hundred Brits now have first-hand experience in Islamic State.

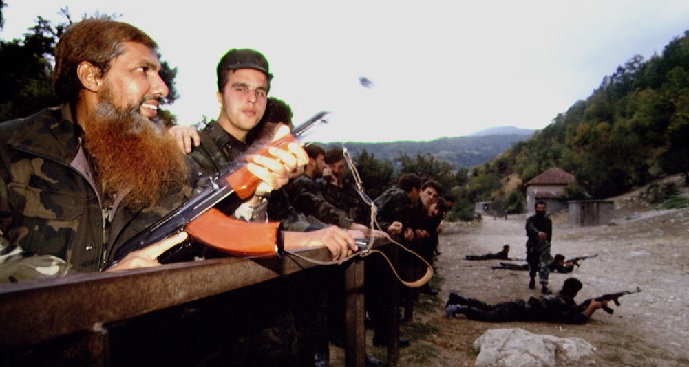

This danger will not be short-lived. The long arc of jihadism inside Britain stretches back 30 years when large numbers of British mujahideen left these shores to fight in Bosnia, Somalia and Chechnya. Nearly 30 years after the Bosnia conflict, some of the jihadi alumni are still haunting us, like the former London public schoolboy who helped murder journalist Daniel Pearl and now looks set for release in Pakistan.

The earliest set of returnees may not have committed any attacks, but their war stories helped to socialise new generations, leading some to call Bosnia the ‘cradle of modern jihad.’ The cohort they produced will likely do the same and metastasise the jihadi threat, which poses a danger because they carry no ideological aversion to attacks at home. For all the controversy, it’s little wonder the government didn’t want them back.

A new generation of jihadists will emerge from the ISIS wound in the coming years. Some will answer the next call to wage jihad overseas, while others will wage an attritional jihad at home. We might be suffering a bout of Jihad nauseam, but the jihadists are not done with us yet.