By attacking transportation arteries, fuel tankers, and population centers in western Mali, the JNIM coalition is targeting the economic, security, and political vulnerabilities of the military junta in Bamako.

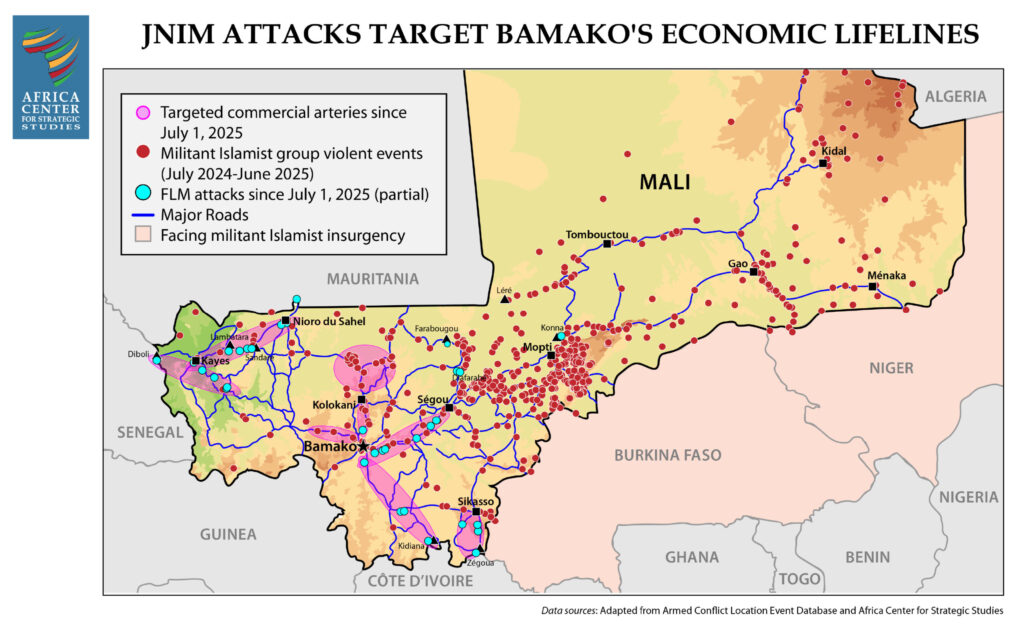

The Maçina Liberation Front (FLM) launched a series of seven simultaneous attacks spanning hundreds of kilometers in western Mali in border towns near Senegal and Mauritania on July 1, 2025. This represented a dramatic shift in tactics and an expansion in the reach of the Jama’at Nasrat al Islam wal Muslimeen (JNIM) coalition of which FLM is the most active member. Over the past year, nearly 20 percent of JNIM violent activity in Mali—resulting in a doubling of fatalities to over 450 deaths—took place in the west and south of the country. JNIM had previously been primarily concentrated in north and central Mali. Only 8 percent of violent episodes linked to JNIM were in western and southern Mali the year before.

Among the towns hit were Kayes (population of 127,000) and Nioro du Sahel (60,000). Kayes is strategic because it sits on the Senegal River, serving as a trade corridor between Senegal and Mali. The Kayes region is the second largest contributor to national GDP after Bamako. Roughly 80 percent of the country’s industrial gold production takes place in the Kayes region.

The attacks represent an explicit economic strategy to cut off and isolate Bamako.

Nioro du Sahel is a cultural landmark, described as the ‘Vatican of Mali’, where hundreds of thousands travel each year for religious ceremonies. It is the birthplace of a branch of the Tijaniyya Sufi brotherhood led by the sharif of Nioro du Sahel, Sheikh Bouyé Haïdara. It is also an important crossroads for transit between Mali and Mauritania.

Marking a new and audacious tactic, the attacks were followed in August by a public demand by JNIM announced over social media in Bambara and Fulfulde, two of the most widely spoken languages in the region. The declaration comprised three main demands:

Kayes and Nioro du Sahel are now under a blockade with residents prohibited from leaving these cities.

All fuel imports from Senegal, Guinea, Côte d’Ivoire, and Mauritania are banned.

One of the largest private transportation companies in the country, Diarra Transport (and its subsidiaries), would be subject to attack should it move on Malian roads.

By targeting Mali’s main overland trade routes, the attacks represent an explicit economic strategy to cut off and isolate Bamako. Petroleum supplies from Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire account for nearly 95 percent of the country’s fuel. Foreign companies have also been targeted. In July, seven foreign-operated gold, lithium, and cement operations were attacked, resulting in the kidnappings of eleven Chinese and three Indian nationals.

The disruptions to transport and commerce raise the risk of severe fuel shortages that could paralyze businesses and other economic activity. A prolonged interruption would cause sharp spikes in fuel and food prices, straining urban populations most dependent on these supplies. The attacks on Mali’s already fragile economy also risk exposing the junta’s inability to provide security as well as its lack of legitimacy.

The military has responded by increasing checkpoints between Kayes and Bamako, especially around Lambatara and Sandare. Lambatara sits on Route National 1 (RN1), roughly 100 kilometers east of Kayes. Fifty kilometers further east on RN1, Sandare is a small town located at the first of several crossroads leading north to Nioro du Sahel. The military has launched operations against FLM bases near both of these towns not far from the Mauritanian border.

Despite the stepped-up military presence and surveillance, FLM fighters have targeted transportation vehicles outside of Kayes and Nioro du Sahel since their declaration. On September 14, a likely FLM ambush on a convoy with military escort resulted in at least 40 fuel tankers being stopped and set ablaze. Passengers from Kayes and Nioro du Sahel have been abducted. Similar attacks, though smaller in scale, have also been reported closer to Bamako and along major routes connecting Bamako to Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea in the south. Diarra Transport, meanwhile, halted its activities within a few days of the August announcement. In short, the attacks have disrupted traffic and commerce throughout western and southern Mali.

Attacks are Strategically and Symbolically Significant

FLM has steadily expanded from central throughout southern Mali over the last year.

The JNIM coalition now exerts much more influence and control over territory in Mali than at any other previous time during the 13-year insurgency. Led by Amadou Koufa, FLM has steadily expanded from central throughout southern Mali over the last year. Mali’s southern regions host 60 percent of the country’s 24 million population, supply most of the country’s food, and anchor its economy. Cotton employs over 4 million people, while industrial mining—dominated by gold but also producing lithium, bauxite, iron ore, and other minerals—drives export earnings. Gold and cotton together account for nearly 80 percent of Mali’s exports.

The growing vulnerability of the economically and religiously significant towns of Kayes and Nioro du Sahel underscores the capacity of FLM to impact the day-to-day lives of all Malians.

Part of an Ongoing Encirclement Strategy

The doubling of militant Islamist group violence in western and southern Mali over the past year represents a steady expansion of FLM’s reach. It can now strike anywhere in southern Mali with relative ease, something that was not the case 2 years ago.

The growing FLM threat in western Mali has caused many to seek refuge outside of the country over the past year. There are now more than 245,000 Malian refugees in Mauritania according to the Mauritanian government—equivalent to roughly 5 percent of the Mauritanian population. Smaller but growing numbers of Malians have also fled to Senegal.

While the attacks in western Mali open a new front, they are part of a broader strategy by JNIM to cut off the main transportation and economic arteries into urban centers around other parts of the country.

Diafarabé and Léré located along the inner Niger River Delta as well as other towns in central and northern Mali have been under a blockade. This has enabled FLM to disrupt transit from southern Mali to northern Mali, making the impacted population centers much more dependent upon JNIM groups for goods.

JNIM coalition fighters are targeting the Bamako-Segou transit corridor that follows the Niger River from Bamako, connecting the capital in the south to central Mali. This move complicates commerce for businesses and logistics for the military.

The fall of Farabougou represents an important marker in the trajectory of the conflict.The strategically and symbolically important town of Farabougou in central Mali’s Segou Region fell under FLM occupation in August 2025. The liberation of Farabougou by the Malian army in 2020 was widely celebrated by the junta and served as a strategic outpost to monitor militant movements between central and northern Mali as well as along the border with Mauritania. The fall of Farabougou, thus, represents an important marker in the trajectory of the conflict. Residents have been forced to abide by FLM’s strict interpretation of Sharia law, including the payment of zakat taxes and the banning of secular music, alcohol, and uncovered women.

Farabougou is roughly 350 kilometers west of Konna, a gateway between central and northern Mali. It was the fall of Konna in 2012 that triggered the French-led Operation Serval that halted the militant Islamist advance on Bamako at that time.

The Malian truckers’ union, Syndicat des conducteurs de camions citernes, (SYNACOR), stopped operations for almost 2 weeks at the beginning of September due to insecurity along routes coming from Côte d’Ivoire. This left roughly 1,000 fuel trucks parked along the border with Côte d’Ivoire following an attack on 3 tanker trucks transporting fuel from Zégoua to Sikasso in southern Mali.

The JNIM coalition’s targeting of primary commercial routes and fuel trucks seeks to sever Bamako from its lifelines while simultaneously asserting control over population centers and regions adjacent to the capital. Without fuel, commodities, and other goods, households and businesses in the most populous regions of the country will face growing hardships. This replicates a similar encirclement strategy observed in Burkina Faso.

Growing Political Repression

Bamako’s growing insecurity and economic vulnerability have occurred in the context of persistent and expanding political repression on the part of the ruling military junta. The military authorities formally dissolved all political parties in May 2025. This followed recurring suspensions of media, political, and civic associations as well as crackdowns on protests against the junta’s continued rule and demands for the return to constitutional order. Political opponents to the junta have been repeatedly jailed with several prominent political leaders seeking exile abroad.

Junta officials have ignored multiple transition timelines since seizing power.

Junta officials have ignored multiple transition timelines since seizing power in August 2020. This was punctuated by a decree in July 2025 by junta leader Colonel Assimi Goïta that named himself president for a 5-year term renewable indefinitely.

Partnering with the Russian mercenary unit, the Wagner Group (later the Africa Corps), human rights abuses and civilian deaths at the hands of the Mali security forces have soared. During the previous 2 years, Malian security forces and their Russian partners were linked to 77 percent (2,194 deaths) of all civilian fatalities resulting from targeted attacks in Mali. This exceeds the number of civilian fatalities caused by militant Islamist attacks and has greatly enabled JNIM recruitment while eroding public trust in the Malian military.

Heightened Security Risk Follows Rejection of Regional Support

The deteriorating security conditions in Mali have followed a systematic process of the military junta decoupling from regional and international security partners. This began with Mali’s withdrawal from the Sahel G5 Alliance in May 2022, then the mandated withdrawal of European Union forces under Task Force Takuba in June 2022. This was followed by the high-profile withdrawal of French Operation Barkhane troops in August 2022. By December 2023, the junta had ended all previous international security partnerships, including the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA). The junta’s rejection of regional and international security support resulted in the paradox of more than 20,000 United Nations, West African, and European forces departing Mali despite the escalating jihadist security threat.

The Mali junta has also withdrawn from regional security cooperation initiatives, including its departure from ECOWAS in January 2025 while ending intelligence sharing with the coastal West African countries despite remaining a part of the Accra Initiative.

These moves have weakened security capacity in Mali while creating an intelligence blind spot for neighboring countries in coastal West Africa. This has resulted in a more permissive environment for JNIM and other militant Islamist groups to operate.

Implications for Mali and the Region

The expansion of FLM into southern Mali and the ability of JNIM to disrupt fuel supplies to Bamako and throughout the country presents a sharp deterioration of security for the increasingly fragmented country.

FLM’s ability to project its influence throughout southern Mali poses increased threats to Mali’s coastal neighbors.

Large population centers in the south—including 3.2 million people in Bamako and 14 million in southern Mali—are increasingly under severe strain as they face growing economic isolation. Similar tactics, though at smaller scales, have been used by JNIM groups to coerce populations under their control in central and northern Mali. Fuel prices have surged in central Mali where authorities have announced a drastic shortage due to the JNIM blockade.

FLM’s ability to project its influence throughout southern Mali also poses increased threats to Mali’s coastal neighbors. The flows of forcibly displaced people from the Sahel into Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mauritania, and Senegal will place border communities under greater strain. Heightened vulnerability to cross-border attacks from militant Islamist groups also risks destabilizing local communities and governments in these countries.