Radicalization in prison has long been a critical issue in the West (and beyond), where prisons have sometimes been turned in recruitment and proselytization hubs by different kinds of extremists, including jihadists. As is well known, one of the main concerns is that radicalized subjects may indoctrinate other common detainees. Italy has also been affected by this phenomenon and jihadist radicalization in prison represents a concrete threat. This analysis presents an overview of the problem, based on the latest available data. As of late 2018, there were 66 detainees who were either awaiting trial or already sentenced for crimes related to “international Islamic terrorism”. These individuals were placed in a special section (the “High Security 2” – AS2 circuit) and were rigorously separated from other detainees. In addition, as of October 19, 2018, there were a total of 478 individuals flagged for radicalization in Italian prisons: 233 in the 1st level – High; 103 in the 2nd – Medium; 142 in the 3rd level – Low. Furthermore, in an attempt to counter violent extremism and radicalization, Italian authorities have been increasingly deporting foreign individuals for national security reasons. In 2018, no fewer than 79 individuals had been expelled upon release from prison. In the face of these new challenges, Italian authorities are strengthening their commitment to identify and counter the threat posed by jihadist radicalization in prison. These efforts include identification and monitoring activities also thorough indicators of violent radicalization, management of extremists after release from prison, training of staff, and rehabilitation initiatives.

The problem of radicalization in prison

Radicalization in prison has long been a critical issue in the West (and beyond), where prisons have at times been turned into recruitment and proselytization hubs by extremists, including jihadists.

This has been a widespread problem across Europe, especially considering the increase in arrests for terrorism cases in the past few years,1 which have bolstered the number of radicalized individuals in prison.

As is well known, one of the main concerns is that radicalized subjects may indoctrinate other common detainees. In fact, their time spent in prison may even become an opportunity to continue the “struggle”, making, so to speak, a virtue of necessity. Furthermore, a common nationality, ethnicity, area of origin and/or language between inmates could facilitate this activity of proselytism.

In addition to these radicalizing agents within prison, there can also be external factors, such as: a) extremist books, videos or websites (often in foreign languages) which can be smuggled inside of detention centers and/or made available to inmates, or b) external visitors.2 For example, in a recent case from February 2019, Spanish authorities arrested a prison worker who was accused of smuggling mobile devices containing jihadist material in exchange for money.

In general, radicalization processes can be favored in a particular context like the prison one, which is already characterized by personal grievances, conditions of fragility and marginalization, and rigid institutional constraints and limitations.

The motivations that can spark a transformation of an individual’s belief systems and behaviors in prison, including a process of jihadist radicalization, are varied: the search for meaning and identity, a desire to defy the authorities or the system in general, but also the need for physical protection.

Furthermore, possible problems in the organization and bureaucracy of prisons can aggravate the vulnerabilities. These criticalities may affect all inmates in general (like, for example, issues related to overcrowding5, shortage of financial resources and understaffing, etc.), but also – even if not in an intentional way – specifically Muslim inmates (in particular, regarding the prison staff’s possible lack of specialized cultural preparation and/or difficulty in handling needs related to their religious practice).

Recent incidents demonstrate that the risk of radicalization among prison guards/officers, however unlikely, cannot be excluded. For example, in January 2019, French media reported that two corrections officers in service in the towns of Lavaur and Seysses, in the outskirts of southwestern city of Toulouse, were suspected of being extremists and had been flagged by authorities in the Fiche S registry for radicalization and terrorism.

Moreover, prisons may even become the theatre of jihadist attacks, as evidenced by the incident that occurred in the prison of Osny, France, on September 4th, 2016, when Bilal Taghi, a 24-year-old French citizen who had attempted to travel to Syria in 2015, deliberately attacked two prison guards with a knife, in the name of the Islamic State.

Furthermore, prisons have played a significant role in the organizational dynamics, activities and narratives of many radical movements and terrorist organizations in modern times, including jihadist groups.

Jihadist radicalization and incarceration

Available data confirms the importance of the prison space for processes of jihadist radicalization in the West. According to ISPI’s database on jihadist terrorist attacks in Europe and North America,9 following the declaration of the establishment of the Caliphate by the Islamic State (June 29th, 2014), a little more than a fourth of the attackers (26 out of 99) had spent time in prison prior to the attack. Interestingly, the charges for which they had been convicted were varied, as only some of them had been detained for terrorism-related activity.

Many high-profile attacks were carried out by individuals with extensive criminal backgrounds who had radicalized while in prison. For example, Anis Amri, the 2016 Berlin Christmas Market attacker, had reportedly undergone a process of jihadist radicalization while serving time in Sicilian prisons.

More recently, the attack in Strasburg, France, on December 11th, 2018, further highlighted this factor, as the attacker, Cherif Chekatt, had reportedly radicalized while in prison and had 27 past convictions in France, Germany and Switzerland.

At the individual level, the nexus between crime and terrorism appears to be strong in contemporary jihadism. According to our original database, out of 99 attackers in the West, about half (49) had a prior criminal background that ranged from terrorism-related activity to theft, drug trafficking, and document forging, etc.

Extremist groups like the Islamic State (IS) have exploited this element for their recruitment, and in particular, have sought to recruit, attract or at least inspire criminals who saw extremist ideology as a way to “redemption” for their past behavior.

Furthermore, from a logistical point of view, the mobilization of criminals can be particularly beneficial for jihadists who can exploit their previous criminal connections to obtain weapons, forged documents, hideouts, etc.11

Similar figures were also observed by ISPI while analyzing the profiles of the Italian contingent of foreign fighters, as out of 125 individuals in 2018, 44% (i.e., 55) had a criminal background and 22.4% (28) had spent time in prison prior to their departure to areas of conflict in Syria and Iraq or, to a lesser extent, Libya.

The general situation in Italian prisons

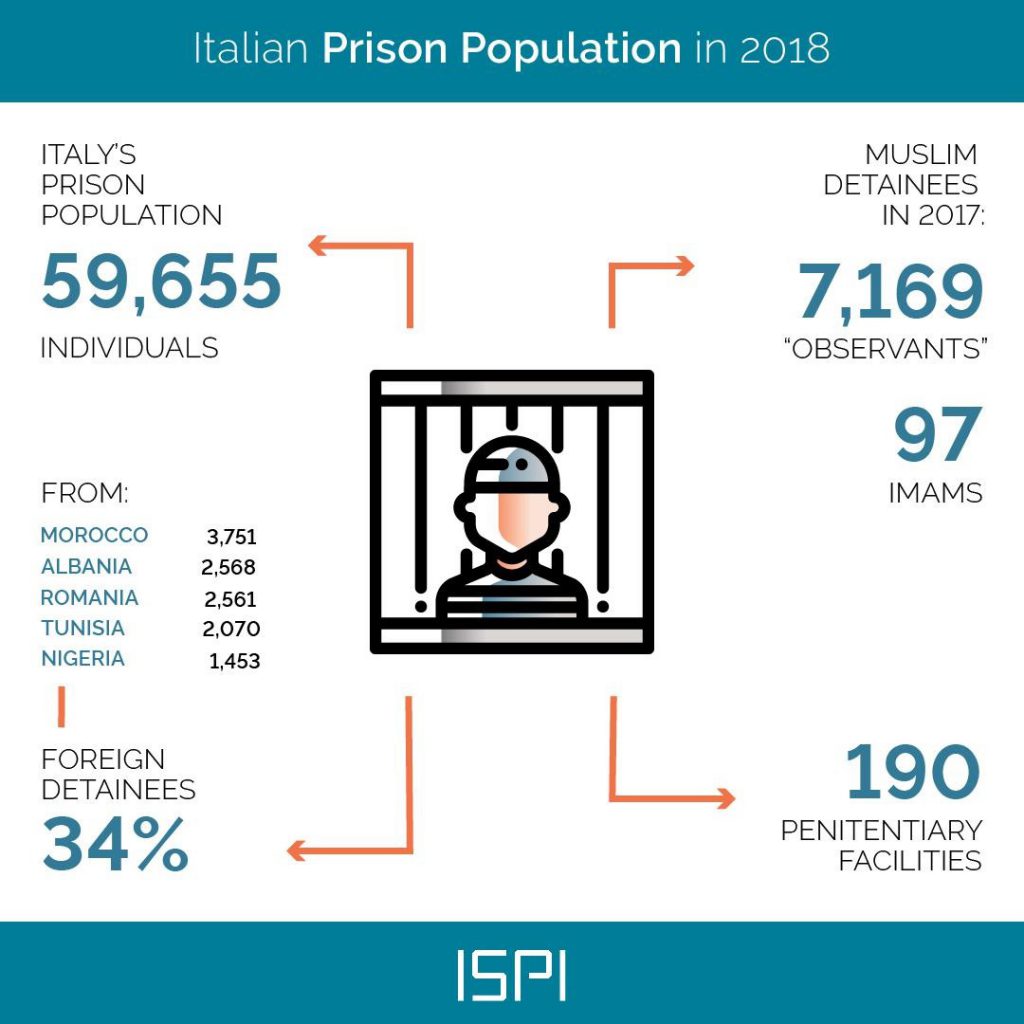

According to the latest official data, in 2018, Italy’s prison population was made up of 59,655 individuals, in 190 different penitentiary facilities spread throughout the country.

The number of foreign detainees was 20,255, representing approximately a third of the total population (33.95%), and the largest foreign inmate populations were those of Morocco (3,751), Albania (2,568), Romania (2,561), Tunisia (2,070) and Nigeria (1,463). Overall, the north African component is the most consistent.

It is relevant to note that in terms of charges and sentencing, the duration of stay in prison for foreigners is, on average, longer compared to that of Italian citizens. This can mainly be attributed to the absence of references on the territory that would allow them to serve sentences outside of the detention centers (community service, house-arrest, work outside of the prison, “semi-liberty regime”, anticipated release). For this reason too, foreign detainees can be more vulnerable to possible proselytism activity by extremists.

Considering the countries of origin, it is possible to estimate that more than 1 out of every 5 detainees is of Muslim faith.16 According to the 2018 report of the Ministry of Justice, among the detainees of Muslim origin, 7,169 were “observant” (osservanti) and conducted prayers according to the norms of their faith. Among these “observant” Muslims, 97 had a role of imam, and thus lead the prayers, 88 had designated themselves as “promotors” (promotori, in other words, they had proposed themselves as the representatives of other detainees to the prison administration), and 44 had converted to Islam while in prison.

Muslim detainees make up a composite and heterogeneous group that is associated with different origins and cultures. As a whole, they tend to differ from the general population: they are mainly males, illegal economic migrants, and have trouble integrating in Italian society.

In Italy, like in many other Western countries, for various reasons, Muslims tend to be over-represented in prison in proportion to the country’s overall population. While no official data on the number of Muslims living in Italy is available, reliable estimates put this number between 1.6 and 2.6 million, corresponding to 4% of the population at most.

In addition to Muslim-born detainees, the phenomenon of inmates who convert to Islam deserves attention. The number, however, is still limited in Italian prisons, and in some cases even spurred by purely opportunistic reasons (in order to be accepted into a group and, for example, benefit from differentiated cell accommodation).20 While, needless to say, religious conversion does not equate to radicalization, numerous studies have suggested that converts tend to be over-represented among jihadist ranks, in proportion to the general population.

A recent interesting case is that of Giuseppe D’Ignoti. This 31-year-old Italian national had been arrested on October 4, 2017, in Sicily for slavery, abduction, sexual assault, and bodily harm, after his Ukrainian partner reported the abuses that she had endured to the police. According to Italian press, D’Ignoti had allegedly threatened to kill the woman and her family, forcing her to convert to Islam, pray with him, and view jihadist execution videos. He had reportedly converted and radicalized in 2011 while serving a 5-year prison term for similar charges, between 2010 and 2015.22 In January 2019, authorities hit him with extremism-related charges in prison, after having uncovered online jihadist proselytism activity that D’Ignoti had carried out prior to his arrest in 2017.

Years before, however, the case of Domenico Quaranta had already brought the spotlight on this phenomenon. In 2002, Italian authorities arrested Quaranta, a 29-year-old Sicilian handyman, for detonating a number of rudimental devices near targets in the city of Agrigento (Sicily) and at a metro station in front of the Duomo of Milan. The man, who had a history of mental health issues, had converted to Islam while in prison, after being introduced to a fundamentalist branch of Islam by his cell-mates, and had acted in what he believed was the defense of a population and creed.24 Interestingly, despite being a neophyte with a limited cultural level and with mental issues, Quaranta reportedly led the prayers in the prison of Palermo, and was even recognized as an imam by other inmates.

Jihadist detainees in Italian prisons

Research regarding jihadist radicalization in Italian prisons is still rather limited. Nevertheless, the phenomenon has undoubtedly affected the country, especially in the past few years.26 For example, the latest annual Report to Parliament of the Italian intelligence system confirms that prisons represent “fertile territory for the cultivation of the jihadist ‘virus’, that is disseminated by incarcerated extremists”.

The latest Report by the Italian Minister of Justice on the activities of the Department of Penitentiary Administration (Dipartimento dell’amministrazione penitenziaria, DAP), published in late January 2019, contains new interesting data in this regard.

First of all, according to this official report, until October 2018 there were 66 detainees who were either awaiting trial or already sentenced for crimes related to “international Islamic terrorism”.29 This marks a slight increase compared to the 62 in the previous year.

These individuals were placed under the “High Security 2” (Alta sicurezza 2, AS2) “circuit” (circuito) that is reserved for “subjects awaiting trial or convicted for crimes related to terrorism (including international [terrorism]), or the eversion of democratic order through violent acts”. Overall, this special high security section currently contains 94 inmates and also includes subjects who were part of domestic terrorist groups such as left-wing (e.g., Red Brigades), right-wing, and insurrectionary anarchist31 extremists.

The subjects arrested or accused of international jihadist terrorism are placed in special sections of the AS2 circuit, which are rigorously separated from the “common” detainees and from the other individuals in the same circuit (domestic terrorism/eversion), in order to avoid the establishment of dangerous connections.

The Italian Department of Penitentiary Administration, DAP, created the High Security circuit in 2009. It is divided into three “sub-circuits” (AS1, AS2, AS3).32 Along with the already mentioned AS2, the AS1 sub-circuit contains “detainees who are part of organized crime groups who have not been placed under the article 41-bis33 security regime” (297 individuals in 2018, according to the 2019 report of the Ministry of Justice). AS3 contains individuals who had high ranking positions in organizations involved in the trafficking of controlled substances (8,795 individuals).

Furthermore, it should be clarified that the AS circuit does not represent a special “penitentiary regime”, with a reduction of rights of the detainee. On the contrary, it features the placement of the detainee in special secure section, heightened monitoring of the individual, and special precautionary measures.

The 66 individuals detained for jihadist extremism have been placed in special designated sections in the prisons of Rossano (in Calabria, southern Italy), Nuoro, and Sassari (both in Sardinia), while a female section in the prison of L’Aquila (in Abruzzo, central Italy) houses two female detainees.

Monitoring of detainees at risk of radicalization in Italian prisons

The Penitentiary Police (Corpo della Polizia Penitenziaria) is responsible for monitoring these detainees. The existence of a police force dedicated exclusively to the prison system ensures a solid monitoring and observation of inmates.

A major role is played by the Central Investigative Unit (Nucleo Investigativo Centrale, NIC), a special unit of the Polizia Penitenziaria which was established in 2007 and reorganized in 2017. It is tasked with the central collection and analysis of information from the various local and territorial units, for the investigation of organized crime and terrorism offences that were committed in the penitentiary context (or that are directly connected to it).

Its personnel takes part in the weekly meetings of the Italian inter-agency committee for the sharing of information and assessment of the terrorist threat – Comitato di Analisi Strategica Antiterrorismo, C.A.S.A. – formed by Police, Carabinieri (national gendarmerie) and intelligence agencies, with the participation of the Guardia di Finanza (Customs and Finance Police) and the DAP.37 The Committee, which was formally established in 2004 within the Ministry of Interior, has played an important role in the Italian counterterrorism strategy by facilitating the sharing of information between law enforcement bodies and intelligence services within the country.

When identifying radicalized individuals within Italian prisons, the Department of Penitentiary Administration, DAP, of the Ministry of Justice makes a distinction between three different profiles:

Subjects detained for terrorism or political-religious extremism (so-called “terrorists”)

Subjects detained for other offences (drugs, theft, etc.), but who espouse an extremist ideology and are charismatic figures within the prison population (“leaders”)

Subjects detained for other offences (drugs, theft, etc.), who appear to be particularly vulnerable to extremist ideology (“followers”).As previously stated, in the case of the so-called “terrorists”, the High security circuit AS2 foresees the isolation of these individuals from the rest of the prison population, thus preventing further indoctrination and recruitment. Furthermore, in order to better manage and monitor these detainees, the NIC has repeatedly stated the necessity to relocate them in small groups of max. 10 people.

As in other European countries, in Italy the so-called “terrorists” are held in a limited number of prisons (concentration), separated from the general prison population (separation) and isolated from each other (isolation),40 living in single cells (if possible, based on the allocation availability).

Thus, the problem of jihadist proselytism and its prevention in prison mainly regards the latter two categories.41 In this regard, it has become imperative to implement the best measures possible to prevent the most vulnerable individuals (mainly the “followers”) from being radicalized by “leaders”. With the increase of the terrorism threat in the past years, the Department of Penitentiary Administration has adopted a number of surveillance and preventive measures in order to counter the phenomenon.

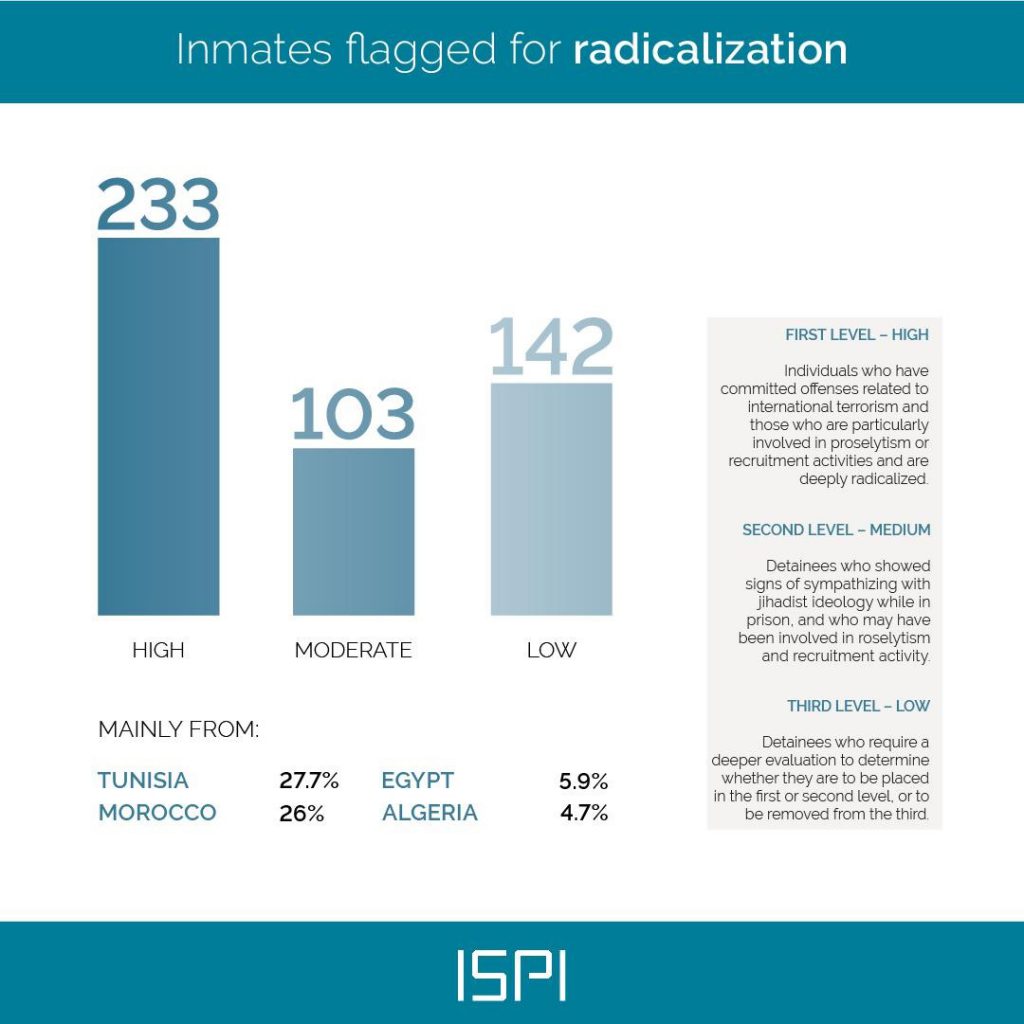

For example, the Department has implemented a system that seeks to flag and monitor radicalized individuals in prison, which categorizes the degree of radicalization of inmates into distinct levels. The categorization begins when a prison flags one of its inmates as having shown signs of possible radicalization. The NIC is then tasked with conducting an investigation to verify and assess the degree of the individual’s radicalization. Officially there are three different levels:

First level – HIGH – includes individuals who have committed offenses related to international terrorism and those who are particularly involved in proselytism and/or recruitment activities and are deeply radicalized.

Second level – MEDIUM – includes detainees who showed signs (or more specifically behaviors) of sympathizing with jihadist ideology while in prison, and who may have been involved in proselytism and recruitment activity.

Third level – LOW – includes detainees who, because of the vagueness of the information received, require a deeper evaluation to determine whether they are to be placed in the first or second level, or to be removed from the third.According to the 2019 official report, as of October 19, 2018, there were a total of 478 individuals flagged for radicalization in Italian prisons, compared to the 506 of the previous year:

233 in the 1st level – HIGH,

103 in the 2nd – MEDIUM,

142 in the 3rd level – LOW.These 478 individuals mainly hail from Tunisia (27.7%), Morocco (26.07%), Egypt (5.91%) and Algeria (4.68%), and most reportedly had “a medium-low level of education”.

During the course of detention, the NIC analyzes all the data regarding life within the prison as well as all contact with the exterior (i.e. correspondence, money sent and/or received, visits, phone calls, etc.) of every inmate placed under observation, at a monthly (First level) or bimonthly (Second level) rate. For subjects in the Third level, the Directorates of the penitentiary facilities are invited to transmit updates whenever new useful information or episodes connected to the risk of radicalization and proselytism emerge, and may indicate the raising of the profile level of the subject.

The system of analysis of information originating from the penitentiary context is based on “observation”, in other words “recording what is seen”.44 Every control on subjects at risk of radicalization is carried out with respect for the protection of sensitive data. Furthermore, in the scope of this monitoring activity, the flow of non-forensic and non-judiciary information is kept separate from the treatment element.

In addition to this reporting, a special protocol has been set up that notifies Penitentiary Police officers of the occurrence of a terrorist attack so that officers can take note of any signs of adhesion and satisfaction of inmates towards these attacks. This protocol was enacted after officers had witnessed detainees rejoicing and exulting after major terrorist attacks had been carried out.

The identification of a radicalization process and its classification represents the first step in the selection of an appropriate prevention activity, such as the deportation of a detainee from Italian territory (upon release from prison) or the placement of an individual in a deradicalization program that is designated by the administrations of the individual prisons.

The information regarding the detainees in the three levels is also relayed by the various penitentiaries to the provincial Prefecture (Prefettura), and contains the reason for the monitoring, the legal status of the individual and his/her release date.

Indicators of jihadist radicalization

In order to improve the monitoring activity, the DAP distributed a series of guidelines, titled “indicators on radicalization”, with the aim of supplying penitentiary facilities with basic instruments/knowledge for the detection of radicalization.

These are individual signs that are meant to be identified and interpreted while keeping in mind the general context, as well as the circumstances of a particular case.

The indicators are taken from the manual Violent Radicalization – Recognition of and Responses to the Phenomenon, by Professional Groups Concerned, which was realized by the Member States of the European Union in a project for the countering of radicalization. These were later adapted to the Italian penitentiary situation by the DAP,46 while considering that the adoption of ideologies and radical positions is primarily a psychological process that manifests itself through a change of mindset, and is not always associated with visible external transformations.

The indicators regard different aspects like the practice of the religion, daily routines of inmates, the organization of the cell, exterior appearance, behavior with others, changes in interests, attention to the media, and comments on politics and actuality.

A particular attention is placed on the necessity to make a distinction between the legitimate practice of religion from that of a process of violent extremism48 – a task that may not be always easy to carry out in practice, especially if the prison staff does not have an appropriate knowledge of Islam. Furthermore, it is widely understood internationally that the correct teaching of religious practice is an especially appropriate measure against jihadist radicalization.

The management of radicalized individuals upon release from prison

Another important step taken by the DAP has been the notification of the imminent release of radicalized detainees to other Italian law enforcement agencies. In fact in the period prior to the release of these subjects, generally at least a month prior, judges and territorial police forces are informed of the imminent release, and are given a report on the monitoring activity in order to help police units identify the appropriate measures that need to be taken.49 These notifications are analyzed on a case by case basis and law enforcement agencies may decide to proceed with special surveillance measures or with the deportation of a foreign individual.

In the past years, expulsions for national security reasons – and, in particular, administrative deportations -50 have played a growing role in the Italian counter-terrorism strategy. In 2018 alone, Italian authorities conducted 117 administrative deportations on the grounds of extremism. The provision can only be employed against foreign individuals present on Italian territory, and once an individual is deported they are issued a prohibition from reentering the country for a period of at least 5 years. As every expulsion is reported to the European Union’s Schengen Information System (S.I.S), deportees are also barred from entering the entire Schengen Area.

According to the latest official report, in 2018 a total of 79 individuals had been deported for national security reasons upon release from prison.

The expulsions also targeted self-declared radical imams in prison, figures who conducted jihadist proselytism activity in this vulnerable environment by exploiting their role in Islamic worship services (for which they often lack the necessary religious knowledge). For example, in January 2019, a 31-year-old Tunisian man, held in the prison of Padua (in north-eastern Italy), was deported after he had violently imposed himself as a self-declared imam, threatening other inmates and engaging in jihadist proselytism.52

International collaboration is also fundamental for the Penitentiary Police and has been considerably strengthened over the years. The NIC, for example, has access to the Terrorist Screening Center’s database, where information from 80 countries regarding individuals who are considered to be dangerous are listed. Furthermore, a number of national databases allow officers to verify whether a detainee or anyone in their immediate family may have been flagged as having links to extremists abroad.

Training of prison staff

Several initiatives have been realized in the past few years that seek to train and educate operators on how processes of jihadist radicalization take place and to provide a basic understanding of Islamic culture, in order to consent a correct analysis and evaluation of legitimate requests by inmates tied to religion (for example, differentiated housing, possibility to eat after sunset during the month of Ramadan, etc.)

The training courses were launched in 2010, and were initially only taken by personnel that managed the AS2 circuit. In particular, the Department of Penitentiary Administration started training its officers to recognize jihadist symbols that may be found in prison cells. From 2011 training courses began to include all penitentiary facilities. Moreover, numerous smaller activity was also held at a local level.

A recent example of this type of initiative is the “TRAIN TRAINING – Transfer Radicalisation Approaches in Training” project proposed by the DAP and the Department of Juvenile and Community Justice of the Italian Ministry of Justice, in collaboration with a number of national and European partners, and mainly financed by the European Commission. The project aims to educate and train personnel on violent radicalization and on how to identify, interpret, and distinguish signals that may indicate that an individual may be undergoing a process of radicalization in prisons and probation.

The challenge of rehabilitation

The flagging and reporting also allows for the placement of a radicalized individual into programs that work towards the rehabilitation of the individual, on a case to case basis.

In general, the Italian penitentiary legislation provides that the particular needs of every inmate are met, and includes the establishment of programs for the re-education and reintegration of detainees into society. The rehabilitation process, established by law and under the supervision of surveillance judges, is tailor-made by a multi-disciplinary team which includes, in addition to the prison police, educators, social workers, social assistants, psychologist, psychiatrists, criminologist and other professionals who are needed on the basis of the profile, crimes committed, and needs of the inmate.

In this respect, it is important to stress that, despite the fact that much of the current discourse about prisons and radicalization is generally negative, prisons are not just a threat. In fact, as confirmed by various studies, they can actually make a positive contribution in tackling problems of violent extremism in society.

In conclusion, the problem of jihadist radicalization in prison has definitely affected Italy, albeit, like jihadist radicalization in general,58 on a smaller scale compared to other European countries. Overall, Italian authorities are strengthening their commitment to identify and counter the threat posed by jihadist radicalization in prison. These efforts include identification and monitoring activities also thorough indicators of violent radicalization, management of extremists after release from prison, training of staff, and rehabilitation programs.