U.S. interests militate against keeping troops in Syria

Core U.S. interests in the Middle East are narrow: (1) preventing significant, long-term disruptions to the flow of oil and (2) defending against anti-U.S. terrorist threats.

Neither U.S. interest justifies keeping U.S. forces in Syria, which holds only 0.1 percent of global oil reserves. U.S. forces originally deployed to Syria to help annihilate ISIS’s territorial caliphate, which was achieved by March 2019.

Since then, the U.S. military presence there has transformed well beyond a counterterrorism mission with a series of murky objectives and needless risks.

Rather than an endless occupation, the U.S. should acknowledge success and withdraw the approximately 900 U.S. troops that remain in eastern Syria.

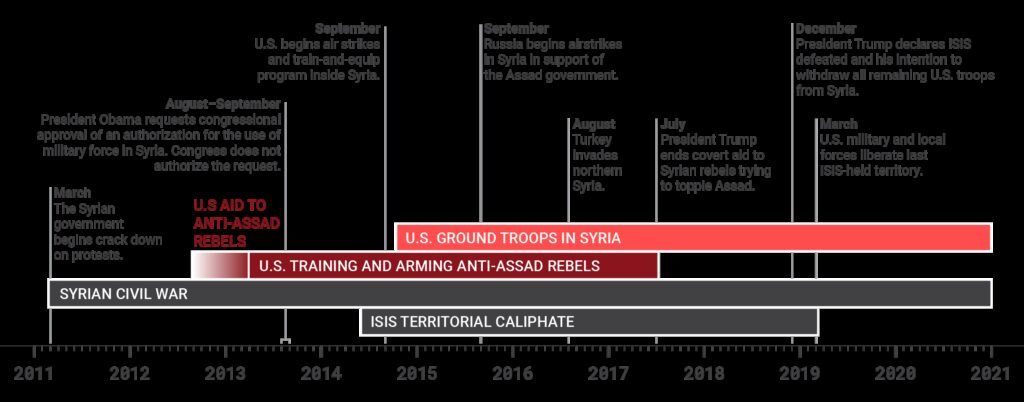

Timeline of U.S. intervention in the Syrian civil war

Around 900 U.S. troops remain in Syria, even after the collapse of ISIS’s territorial caliphate.

The evolution of the U.S. intervention in Syria

The Syrian government’s violent crackdown against its opponents beginning in 2011 precipitated a reluctant Obama administration to support a weaker anti-government rebellion with arms, training, and diplomatic support in the following years.

Had this regime-change campaign via proxies succeeded, it might well have been a “catastrophic success” that installed a jihadist government while leading to new phases of civil war.1

U.S. support for rebels convinced Russia and Iran to redouble their own military assistance to Damascus—worsening the civil war—and badly failed.2

As ISIS gained power, the U.S. directly intervened militarily in Syria toward degrading and eliminating the group's territorial caliphate. U.S. airstrikes, coupled with Kurdish- and Arab-led ground operations assisted by U.S. SOFs, accelerated under President Trump. Congress never authorized sending U.S. forces into Syria.

With ISIS’s caliphate collapsed by early 2019 and its remnants scattered, U.S. objectives shifted yet again—in large part to preventing Russian and Iranian influence in Syria and spoiling a complete Syrian government victory by depriving it of oil revenue.ISIS is a spent force

At its height, as many as 8 million people lived under ISIS’s self-proclaimed caliphate across Syria and Iraq. Today, ISIS no longer controls any territory, boasts a small and disorganized fighting force, and faces multiple stronger adversaries.

Unlike in 2014 and 2015, ISIS lacks the capability to conduct or inspire large-scale attacks and take (and hold) major cities.

ISIS’s attacks today are largely opportunistic, center on easy targets, consist of primitive hit-and-run operations, and have no strategic impact.3

The approximately 900 U.S. troops still in Syria are no longer needed to combat ISIS and should withdraw. Local forces—including the Syrian government, Turkey, the Syrian Democratic Forces, and pro-Damascus militias—have both the incentive and capacity to deal with the ISIS’s remnants.Keeping U.S. troops in Syria prolongs the civil war

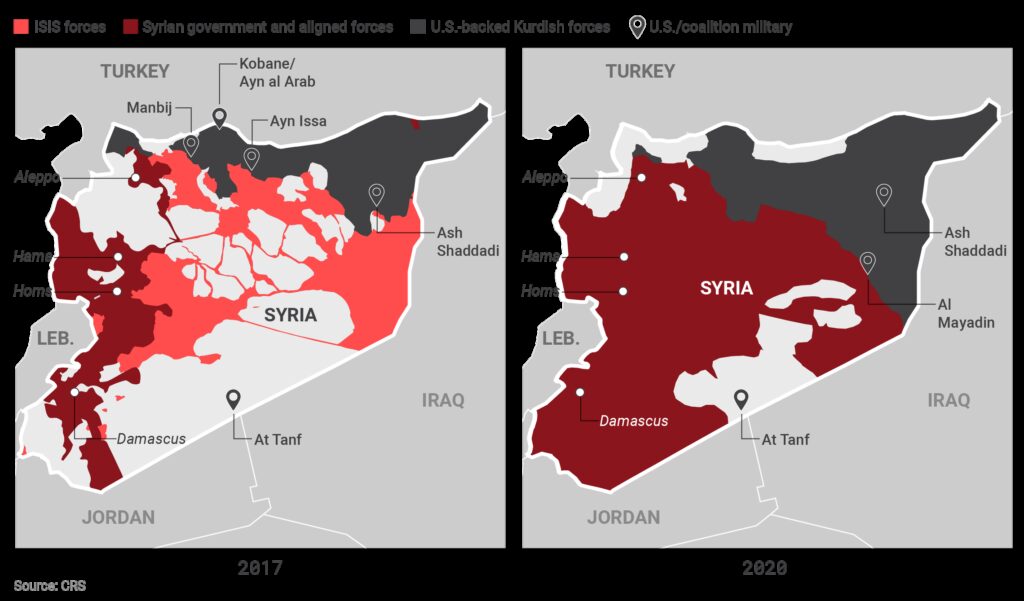

Through brutal force and the backing of foreign partners, like Russia and Iran, the Syrian government has largely vanquished the armed opposition, in particular the heavily populated west from Damascus north through Homs, Hama, and Aleppo.

Except for the areas of Syria’s Idlib Province, controlled by Turkey, and Kurdish-held areas in the northeast, backed by U.S. military forces, Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad’s forces control the country’s population centers and key transportation nodes.

Maintaining a U.S. military presence in eastern Syria merely delays what is likely to be a full Syrian government victory—the stronger party in the civil war. While an Assad victory is undesirable, prolonging Syria’s civil war exacerbates suffering there.

Tasking U.S. troops to protect Syrian oil in the east, as the Trump administration stated, complicates Damascus’s plans to consolidate power but only at the high cost of maintaining a perpetual, risky U.S. deployment in a strategic backwater.4Syrian civil war by territory controlled

The ISIS territorial caliphate has collapsed in Syria, and the U.S. military presence today prolongs a civil war and endangers U.S. troops to spoil a complete Syrian government victory and deprive it of oil revenue.

Keeping U.S. troops in Syria courts war with larger powers

For the U.S., Syria’s geostrategic position is insignificant. It has no notable natural resources, international waterways, or other kinds of strategically important attributes. U.S.-Syria relations have long been poor.

The situation is different for Iran and Russia, both of which have expended enormous military, economic, and diplomatic resources to ensure the survival of a long-time partner in Damascus. For Russia and Iran, a Syrian government victory would be a return to the status quo—not an expansion of power in the Middle East.

Keeping U.S. forces on the ground increases the risks of confrontation with Syrian, Iranian, and Russian forces—and possibly our own NATO ally Turkey. Such a scenario could spark all-out war in the region.

U.S. troops have already engaged in dangerous skirmishes with Iran-backed forces, Russian mercenaries, and regular Russian army units. Fights with Assad-backed forces are increasingly likely.

Preserving a U.S. military presence to frustrate Iran's or Russia’s status-quo ambitions in Syria courts wider conflict with both powers, a dangerous and unnecessary distraction from true strategic priorities.5

The existence of a Syrian government backed by Russia and Iran is not preferable but does not hinder core U.S. interests in the Middle East. Leaving these powers to exercise influence in war-torn Syria is no gift to them.Recommendations on the way forward in Syria

Withdraw all remaining U.S. forces in Syria, recognizing the U.S. military mission to defeat ISIS’s territorial caliphate has been accomplished.

Offload Syria’s internal problems onto Russia, Iran, and the Syrian government, who have effectively won the civil war.

Support, rather than obstruct, Kurdish efforts to negotiate an acceptable modus vivendi with the Syrian government. A prospective deal could include Damascus reclaiming control of Syria’s borders—providing the Kurds protection against further Turkish advances—in exchange for negotiated autonomy in Kurdish-dominated areas.

Learn the lesson that the U.S. should not engage in regime-change operations under all but the rarest circumstances.6 Regime-change fractures societies, turns the U.S. into an occupying power, and unleashes chaos that produces humanitarian disasters. Backing the weaker side of a civil war worsens and prolongs violence, increasing casualties and destruction.Endnotes

1 Benjamin H. Friedman and Justin Logan, “Disentangling from Syria’s Civil War,” Defense Priorities, May 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/disentangling-from-syrias-civil-war.

2 Richard Hanania, “Worse than Nothing: Why U.S. Intervention Made Government Atrocities More Likely in Syria,” Survival 60, No. 5 (2020): 173–192, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00396338.2020.1819653.

3 Gil Barndollar, “Dealing with the Remnants of ISIS,” Defense Priorities, February 2020, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/dealing-with-the-remnants-of-isis.

4 Michael Crowley, “‘Keep the Oil’: Trump Revives Charged Slogan for New Syria Troop Mission,” New York Times, October 19, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/26/us/politics/trump-syria-oil-fields.html.

5 “Escaping the Syria Trap,” Defense Priorities, October 2019, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/escaping-the-syria-trap.

6 Richard Hanania, “Worse than Nothing: Why U.S. Intervention Made Government Atrocities More Likely in Syria.”