The central media apparatus of the Islamic State group is mis-reporting on the activities of its cells in central Syria. Rather than exaggerating their capabilities, something that it is conventionally assumed to be doing all the time,1 its Central Media Diwan appears either to be deliberately under-playing them, or, less likely, to be unaware of their full extent, possibly due to communication issues. Indeed, there is a significant disconnect between what the Islamic State is saying its cells in central Syria are doing versus what its adversaries are saying they are doing. This is starkly evident in the fact that the vast majority of attacks that pro-regime sources attributed to the Islamic State in the Badia, Syria’s expansive central desert region, in 2020 went entirely unclaimed by the group, according to data collected and cross-analyzed by the authors. Based on the dynamics that characterize this data, which is supported by fieldwork inside Syria, it appears that this under-reporting on the part of the Islamic State, which has continued unabated into 2021, is at least partially intentional. This suggests that its covert network in Syria may be attempting to surreptitiously establish a strategic hub in this remote central region, something that could act as a rear base for a resurgence in the rest of the country and Iraq in years to come.

- Introduction

A little after 2:30 PM Damascus time on April 6, 2021, Facebook users in the Syrian city of Salamiyah began posting about an Islamic State attack in rural Hama in which a large number of residents from the village of Sa’an had been captured. Soon after, others began posting that several members of the pro-regime National Defense Forces (NDF) had been admitted into Salamiyah’s central hospital. That evening, details emerged about exactly what had happened: a group of some 60 civilians and NDF fighters had been ambushed by Islamic State militants near the Tuwaynan Dam, along the Homs-Hama border, and most if not all of them had been captured alive. After back-channel negotiations, the majority were freed later that same day, with local news sources reporting that around 50 of them had been released in exchange for detained family members of the Islamic State fighters.2

This brief episode demonstrated with alarming clarity that the Islamic State is alive and well in central Syria — specifically in the parts of rural Homs, eastern Hama, southern Aleppo, southern Raqqa, and western and southern Deir ez-Zor that are collectively known as the Badia. In this often-overlooked part of the country, its network is clearly capable of mounting complex ambushes on large targets and, an even greater concern, going back to ground in areas beyond the reach of its enemies.

Given the scale and success of April’s Hama kidnapping, it might have been expected that the Islamic State would have leaped at the opportunity to trumpet the raid in its global propaganda output. After all, it has been known to publish full write-ups about attacks that were much smaller, and much less successful, than this one. However, counter-intuitively, amidst the hundreds of reports, photo-essays, video clips, and articles that it has published in the weeks since, the Islamic State’s Central Media Diwan did not once mention or allude to the incident.

This was not a one-off episode. Rather, reporting discrepancies like this have been occurring for years now. Based on the fact that Islamic State reporting appears to be mainly accurate in other regions of Syria,3 the discrepancies in its Badia claims seem to be the product of either a deliberate, systematic, and sustained campaign of misdirection, an inability on the part of its Central Media Diwan to keep abreast of what is going on, or a combination of both.

This report explores this phenomenon by cross-analyzing two datasets. The first dataset consists of what the Islamic State said it did in the Badia in 2020, while the second dataset consists of what local pro-regime sources said the Islamic State did there in 2020. While the Islamic State officially claimed just 73 attacks in the region across the whole of that year, it was reported by local regime loyalist sources to have conducted an additional 224 operations there, killing at least 316 in those unclaimed attacks. On close inspection, the Islamic State claimed just 25% of the attacks in this combined dataset, a figure much lower than what has been reported from places like northeast Syria.

The Islamic State’s undercounting in central Syria seems to be an anomaly. The authors have tracked the group’s attack claims around the world since 2016 and are not aware of it undercounting attacks in any other part of the world to anywhere near the same degree. Indeed, the surprising data disconnect in central Syria was the reason for writing this report. But the authors acknowledge they do not have data to establish baselines on whether and to what degree the Islamic State has undercounted attacks globally. In the post-caliphate era, it could be that the Islamic State’s central leadership has adjusted its long-held tradition of sustained media output from every wilaya in favor of strategic silence in key regions as it attempts to rebuild critical networks under the radar of the international coalition. A global metrics study of this kind would be invaluable and could either buttress or lead to a re-evaluation of the notion that the Islamic State’s under-reporting from Syria is as significant an anomaly as the authors believe it to be. Based on their extensive experience working with data of this nature, it seems fairly unlikely that the latter scenario would be the case.

After setting out the data collection and analysis methodologies used to arrive at these findings, this study explores tactical, targeting, and geographic trends in each dataset. This discussion is then used to assess the applicability of a set of six hypotheses that could explain the reasons behind this disconnect in the two datasets:

Hypothesis 1: Criminal gangs are responsible

Hypothesis 2: Iran-backed militias are responsible

Hypothesis 3: Loyalists are over-reporting

Hypothesis 4: Strategic silence

Hypothesis 5: Communication difficulties

Hypothesis 6: Organizational fragmentation/splinteringThe authors conclude that, while it is impossible to fully rule out the first three hypotheses, their validity, even if combined, would be limited and not impact the overall trends both observed in the data and supported by interviews on the ground. On that basis, the specific nature of this reporting discrepancy is assessed to be more likely accounted for by a combination of the latter three, Islamic State-driven scenarios.

- Methodology

This study draws on two complementary sets of data, each of which was run through and processed by ExTrac, a conflict analytics system co-developed by the second author.4

The first dataset was compiled from the Islamic State’s official propaganda channel on Telegram. It comprises every operational claim published via Nashir, the group’s official media distribution network, and Al Naba, its weekly newspaper, in relation to the Badia in 2020. Its start date is January 1, 2020, and end date is December 31, 2020. For sake of clarity, this dataset is henceforth referred to as “the Nashir/Naba dataset.”

The second dataset, henceforth referred to as “the loyalist dataset,” was compiled from public and private pro-Syrian regime Facebook pages and via interviews with pro-regime soldiers. The Facebook sources include community pages, unit pages, and personal profiles.

Trends in each dataset were cross-referenced through interviews between the first author and both pro-regime soldiers and officials in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

2.1 The Nashir/Naba dataset

All the reports contained in this dataset were collected by the second author exclusively from the Islamic State’s closed-access feed on Telegram, a privacy-maximizing social media platform favored by violent extremists for propaganda distribution (among other things), as well as from the Islamic State’s newspaper, Al Naba.5

Across 2020, as was reported in the August 2020 issue of the CTC Sentinel, “two outlets on Telegram were charged with distributing all official Islamic State communications in relation to its activities in [Syria (not to mention the rest of the world)]: the Nashir network, which was tasked with disseminating materials produced by central and provincial media units; and the Amaq News Agency, which essentially acted as its newswire service. Operating alongside these was a separate, supporter-run dissemination hub called the Nashir News Agency. (Note: despite the name, this entity is distinct from Nashir, which is internal to the Islamic State.) Throughout [2020], the Nashir News Agency aggregated all posts from both Nashir and the Amaq News Agency on a minute-by-minute basis. It was from this hub, the Nashir News Agency, that the bulk of this dataset was compiled.”6 A number of claims were also collected from the Islamic State’s newspaper Al Naba, which occasionally publishes “exclusive” reports about Islamic State activities that do not appear elsewhere.

Prior to the analysis, the authors filtered the Nashir/Naba dataset so that it only contained operation claims published in 2020 in relation to the Badia. This involved removing all photo, audio, and video files. This was done to help avoid duplication.7

In total, this process resulted in the exclusion of several thousand pieces of content from the corpus, leaving 73 official Islamic State attack reports relating to its activities in the Badia in 2020, with each report corresponding to an individual, separate, and distinct attack. Each of these claims was manually checked to make sure that no duplicate reports found their way into the dataset.

Once the Nashir/Naba dataset had been compiled and cleaned, each report in it was entered into the ExTrac conflict analytics system, wherein they were automatically coded and analyzed according to several criteria, among them:

Week and date of the attack (see Figure 1 below);

Lethality of the attack (i.e., number of kills reported in each claim) (see Figure 3);

Longitude and latitude of the attack location (see Figure 4);

Sector and region to which the report relates;

Weapons used in the attack;

Attack type (i.e., ambush, assault, assassination, bombing, etc.) (see Figure 2);

Target (i.e., Syrian Arab Army, SDF, etc.);

Target type (i.e., military, intelligence, civilian, government, etc.); and

When mentioned, number of kills reported.2.2 The Loyalist Dataset

In Syria, the information environment is cloudy, incomplete, and characterized by a plethora of overlapping but often-discrete sources. In the context of the central Syrian Badia, information on the day-to-day military activities of regime and pro-regime forces primarily comes from Facebook pages and researcher interviews with participants on the ground. Accordingly, aspects of the information available for studies of this kind can be marred by the diverse agendas of the parties involved in the reporting.

For loyalist sources, such dishonest reporting most often takes the form of under-reporting of their own losses and over-reporting of enemy losses. However much public discussion of battlefield losses is repressed, though, martyrdom announcements still routinely appear on pro-regime Facebook pages. These announcements can provide a baseline for tracking the ebb and flow of combat across the country, and when properly vetted with interviews, help to provide a clearer picture of the situation on the ground than could be ascertained without them.8

With the above in mind, all the reports contained in this dataset were collected by the first author from loyalist pages on Facebook and validated and/or nuanced through interviews with local journalists and loyalist fighters in the Badia. They relate only to the Badia and no other part of Syria.

Prior to 2011, Syria had no independent local news outlets, only central government-run national news. But with the outbreak of war, both pro- and anti-government communities, individuals, and groups created Facebook pages to spread news and propaganda and to organize locally. As protests and military action escalated, these pages became the main source of breaking news about battles occurring across the country and for friends and families to mourn the men killed on their respective side. Nowadays, these Facebook pages are central hubs for communal and unit online interactions, allowing as they do loyalist Syrians to discuss normally taboo topics like battlefield losses and military operations.9

Today, loyalist Facebook pages report on attacks on civilians and security forces in the central Syrian Badia — where both the regime’s army and an array of loyalist militias are stationed — in a number of ways. The first is through martyrdom commemoration — i.e., posts in which fallen fighters are commemorated by their communities and loved ones. These reports usually comprise a range of information, anything from a fighter’s hometown and unit to where and when he died.10

While martyrdom commemoration reports shine important light on regime and allied militia clashes with the Islamic State’s cells in the Badia, they have their limitations. Many loyalist deaths go unreported, sometimes because bodies cannot be recovered or because those killed are listed as missing and their families not notified. Because martyrdom reporting is a communal activity — relying on family, friends, or community leaders to publicize “notable” martyrdom stories — this means that many deaths (and the incidents that caused them) go unreported.

Moreover, members of factions that were once opponents of the regime before later reconciling and fighting alongside it in counter-Islamic State operations rarely receive public honors — and if they do, these do not tend to manifest outside of their own immediate communities. This makes it particularly difficult to find out about attacks on members of former opposition groups or men from former opposition towns deployed to the Badia. Aside from them, the deaths of poor and unmarried loyalist fighters also often go unreported as there is no one in their hometowns with the means or inclination to share the news of their martyrdom. All this is to say that martyrdom reporting provides a low-end number for regime and regime-allied casualties in the Badia.11

In addition to martyrdom commemoration, there are several loyalist pages on Facebook that routinely report news on clashes between Islamic State cells and regime forces. While their coverage often lacks details on the respective severity and scale of these clashes, these reports usually include enough specific information, or are shared across a large enough range of consistently reliable pages, as to be considered credible and validated.12

Occasionally, there are claims of fighting in the Badia that use extremely vague (and usually overtly pro-regime) language, generally along the lines of “Fierce clashes in the Badia right now as the heroes of the Syrian Army destroy the Daesh remnants.” These posts are not shared by pages the authors of this study trust and rely on and are clearly meant as morale-boosting propaganda, rarely referencing any real attacks. In such cases, which generally occur only a couple times each month, the claimed event was not included in the loyalist dataset.

As with martyrdom announcements, this stream of loyalist news reporting has its limitations. This is because it relies first on information from the frontlines reaching page admins intact, and then on those page admins choosing to report the information publicly. Moreover, loyalist pages, like every other faction fighting in the Syrian war, have their own biases and internal censorship. According to Syrian analyst Suhail al-Ghazi,

“[W]hen it comes to losses, all pages minimize loss and exaggerate the enemy’s loss. They rarely publish specific numbers and […] they also don’t publish names of MIA soldiers at all. Communities, units, and individuals will often avoid publicly naming martyrs, or even announcing that a clash occurred, due to the regime repeatedly cracking down on individuals who publish ‘harmful’ news. In the past several years, many pages’ admins faced detention or threats because they were critical of the government’s policies.”13

As in the case of martyrdom notices, this internal pressure against reporting on fighting results in an undercount in the data.

Crucially, both martyrdom commemoration notices and local news reports always state who was involved in the incidents being described. Usually, they opt for the moniker of “terrorist remnants,” which is the regime’s favored terminology for the Islamic State’s cells in the Badia. Less often, they will explicitly use the term “Daesh” or more vaguely speak of “armed groups,” something that has been used in the context of both criminal gangs and the Islamic State. On the occasions that such reports appeared, the first author followed up with local contacts to ascertain responsibility and filter out irrelevant, criminality-driven clashes.14

Importantly, while it draws on them for reference purposes, this dataset does not include any information solely reported by anti-regime outlets such as the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, Deir ez-Zor 24, Ain al-Furat, and Zeitun Agency, among others, which frequently publish false news about supposed Islamic State attacks on regime forces and their allies in the Badia. According to Elizabeth Tsurkov, a leading authority on local Syrian opposition dynamics, some of these outlets pay local regime fighters for news, something that encourages informants to routinely create fake stories in order to receive more payments.15 Furthermore, a portion of the funding they receive is tied to levels of online engagement, something that incentivizes their occasional publication of sensationalist news.16 These factors, as well as others, mean that such outlets often end up publishing reports on Islamic State attacks in the Badia that ultimately turn out to be false.17

With the above limitations in mind, the first author implemented a rolling qualitative protocol to ensure the accuracy of the loyalist dataset. This involved triangulating and nuancing it through interviews with loyalist fighters who were either deployed to the Badia or had contacts in it. These interviews, which were conducted continually across 2020, were used to verify and provide additional details on some already-reported attacks, glean information on unreported attacks when possible, and check the validity of claims about attacks made by pro-Islamic State and opposition outlets. These interviews were also used to confirm that the trends that emerged each month in the data — the geographic spread of attacks, the rate and type of attacks, and regime responses to attacks — matched the reality on the ground.

In total, this layered collection process resulted in 262 loyalist reported Islamic State attacks in the central Syria Badia between January 1, 2020, and December 31, 2020, 38 of which coincided with Islamic State claims (see section 2.3 below). These data points were coded and analyzed according to the same criteria that were used in the context of the Nashir/Naba dataset.

It is important to note that, due to the factors mentioned above, the loyalist dataset as a whole almost certainly comprises an undercount of the full spectrum of violent activities in the Badia. Some might assume that loyalist sources would exaggerate the level of violence in the region in order to legitimize their presence there, but, as discussed above, such motivations do not exist within the domestic political and local community environments in which these posts are shared. Given that, and the fact that data points containing vague or minimal details were further verified by the first author’s cross-checking with trusted sources in the region, this dataset can arguably be considered a minimum baseline against which the Islamic State’s own data can be compared.

2.3 Reconciling the Datasets

All in, the full Nashir/Naba dataset contained 73 Islamic State attack claims with each claim relating to a discrete Islamic State attack in the Badia in 2020. For its part, the loyalist dataset contained 262 reports of Islamic State attacks in the Badia in 2020 with each report relating to a discrete attack.

After the authors manually cross-checked each dataset, removing any data points that referred to attacks that had reportedly occurred on the same day, in the same place, and using the same modus operandi, it emerged that there were 297 unique attacks claimed/reported in the Badia in total across 2020, with just 38 of them being claimed/reported by both the Islamic State and loyalist sources.

- Key Trends

This section compares key trends in each of the datasets. First, it looks at the quantity and quality — i.e., scale, complexity, and impact — of Islamic State-reported versus Islamic State-attributed attacks. Second, it turns to targeting trends — and any discrepancies — that characterize each dataset. Third, it analyses the attacks from a geographic perspective, describing an array of locational differences between what the Islamic State reported from the Badia in 2020 versus what loyalist sources attributed to it in 2020.

3.1 Rate of Attacks

Figure 1 (above) shows all Islamic State-reported and loyalist-reported attacks in the Badia in 2020. It shows that the Islamic State consistently reported significantly fewer attacks in the region than were attributed to it by loyalist sources during the same period. It also shows that the difference between the two figures was greatest in September and October, when the Islamic State reported around 90% fewer attacks than were attributed to it by loyalist sources.

Figure 1 also shows that, per the Islamic State’s own data, its attacks in the Badia came in three waves: one small wave in the month of January, and two larger waves in July-August and November-December. The first of these is consistent with a Syria-wide trend that saw Islamic State militants carrying out significantly more attacks than usual as part of a global campaign dubbed the “raid to avenge the two sheikhs.” This was launched in the last week of December 2019 as a belated response to the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the Islamic State’s former leader, and Abul Hasan al-Muhajir, its former spokesman, in late October of that year. The second wave in July-August 2020 is loosely consistent with another of the Islamic State’s global campaigns, its summer “raid of attrition,” which was launched at the end of July to mark the first 10 days of the Islamic month of Dhul Hijjah. The third wave of attacks, which occurred in November-December 2020, did not coincide with any stated campaigns by the Islamic State. On that basis, it appears to have been driven by dynamics internal to the Badia, rather than a centrally coordinated global Islamic State campaign.

Interestingly, reporting trends in the loyalist dataset only partially correlate to those that characterize the Nashir/Naba dataset. The periods of intensification that loyalists reported occurred at different times to those that were reported by the Islamic State — i.e., April-May and August-October, rather than January, July-August, and November-December. Moreover, the second, August-October, wave was far more sustained than any of those reported by the Islamic State, lasting a full 90 days as opposed to just one or two weeks straddling the beginning or end of a month, as was the case with all three of the Islamic State-reported upticks.

The August-October surge indicated by loyalist sources marked the beginning of a large, sustained expansion of Islamic State operations into eastern Hama, as well as a three-fold increase in loyalist and Islamic State reported activity in southern Raqqa and a 30% rise in loyalist and Islamic State reported activity in rural western and southeastern Deir ez-Zor. These expanded Islamic State activities were likely motivated by both regional strategic considerations — i.e., a desire to secure and consolidate territory — and tactical opportunism — i.e., a desire to take advantage of the scarcity and/or weakness of regime forces.

3.2 Scale of Attacks

On comparison, the Nashir/Naba and loyalist datasets exhibit significant discrepancies in the reported impact of Islamic State attacks in the Badia in 2020. Per the Islamic State, its cells’ attacks there across the whole year killed 196. Per loyalist sources, however, this figure was much greater, with some 409 reportedly killed in Islamic State operations. The point at which there was greatest divergence was in August, when the Islamic State reported just 20 kills as opposed to the 71 reported by loyalists.

Generally, the number of kills reported in the context of a given Islamic State attack is a useful, albeit imperfect, proxy measure for the tactical sophistication of the attack itself. However, the seemingly significant underclaiming of Islamic State attacks in the Badia makes this metric difficult to measure. Examining only those attacks claimed by the Islamic State results in 2.6 kills per attack on average over the course of the year. Yet when the attacks reported by loyalists and not claimed by the Islamic State are included, this drops to 1.4 confirmed kills per attack on average.

The weakness of this methodology is due to the conflicting reporting methods of each party. The Islamic State is far more likely to inflate enemy losses in its claims — as it did on at least three occasions in 202018 — than to underestimate them, thus inherently leading to a higher kill per attack average. Loyalists, by contrast, are much more likely to under-report losses to Islamic State attacks, rarely giving full numbers of killed and wounded and never inflating losses. This inherently leads to a lower kill per attack average.

Rather than use lethality to assess the sophistication of Islamic State attacks, the authors have introduced the metric of “high quality” attacks. In the context of the Islamic State in the Badia, an attack is considered “high quality” if it had any one of the following five attributes: i) caused three or more deaths (note: three deaths is a high baseline in the context of the Syrian Badia, where many regime patrols are conducted by just one or two vehicles and outposts are manned by only a handful of soldiers, but would not be somewhere like northeast Nigeria, where the Islamic State’s attacks are generally on a bigger scale); ii) involved the use of false checkpoints; iii) occurred deep in “secure” regime territory; iv) had multiple stages or played out across multiple fronts; v) resulted in the capture of regime positions or fighters.19

This allows for a more holistic and region-specific approach to assessing the Islamic State in the Badia, accounting for the reality that on many occasions throughout 2020 regime forces fled in the face of Islamic State attacks, enabling the group to seize weapons, vehicles, and positions in attacks that resulted in no deaths. The metric further accounts for when militants infiltrated behind regime lines. Whether or not such attacks led to high numbers of dead, they indicate the cell’s sophisticated intelligence-gathering capabilities.

Figure 2 (below) shows “high quality” attack reporting according to both the Islamic State and loyalist sources across 2020. As in Figure 1, there is a significant discrepancy between the two datasets, with the Islamic State generally claiming less than half as many high-quality attacks as were attributed to it by loyalist sources in all months apart from January, when it reported two more than loyalists did.

The Islamic State’s sustained ability to deploy high-quality operations in the Badia across 2020 presents fairly unequivocal evidence that its cells possess extensive operational and intelligence-gathering capabilities. Counterintuitively, these capabilities are only really reflected in the loyalist dataset, not in the Islamic State’s own reporting, suggesting that its central media apparatus either did not know about them, or was unwilling to shed light on them. Given what is known about the tight structure of this group’s military-media reporting nexus, which has been consistent and systematized since it was formally consolidated in 2016, as well as the general state of health and functionality for the overarching media apparatus in Syria today, something that the authors are tracking daily, the former option seems somewhat unlikely.20

3.3 Targeting Trends

The Nashir/Naba and loyalist datasets are at their most similar when considered from the perspective of whom it was that was being targeted. Per both, the vast majority of Islamic State-brokered violence across 2020 targeted local security forces stationed in the Badia — whether that is the regime military or its allied militias.

When it came to the targeting of civilians, however, the Islamic State reported just a tenth as many non-combatant kills as were reported by loyalists while claiming only a third of the total number of attacks on civilians ascribed to it by loyalists. (See Figure 3 right.) Moreover, on a number of occasions, the Islamic State framed attacks on non-combatants as attacks on military targets. To an extent, this is to be expected, given that it looks “better” for it to be attacking and killing active adversaries than unarmed civilians. Notably, this same diversionary approach toward reporting attacks on non-combatants is regularly practiced by the Islamic State in other places, most prominently of late in Africa.21 There is also a chance that this discrepancy is heightened by loyalists wrongfully framing Islamic State attacks as having targeted civilians, something which could have been done in a number of instances (though, due to the locations from which these incidents were reported, were only likely to be a minority).

However, while the relative absence of Islamic State reports about attacks on civilians is to be expected, the same cannot be said for the relative absence of Islamic State reports about attacks on officers in the Syrian regime’s military or NDF. Across 2020, just five of the 22 attacks that targeted regime and regime-aligned officers were claimed via its central media apparatus.22 The remaining 17 attacks were left entirely unreported by the Islamic State, even though they were significant strategic wins for it. This is more likely to be a deliberate ploy than something born of a lack of information on the part of the Islamic State, which, elsewhere in Syria or in places like Iraq or Afghanistan generally makes sure to highlight attacks in which officers are killed (even if that means doing so retrospectively).

Even if it is deliberate, this under-reporting of attacks on mid- to senior-ranking military officials could also in part be explained by the fact that some of the 12 attacks conducted with IEDs and mines were ones the Islamic State had planted indiscriminately months earlier.23 However, the Islamic State only claimed three of the at least eight attacks on commanders conducted through small-arms ambushes (meaning that Islamic State militants were present at the scene of their deaths).24

The fact that the group still refrained from reporting on most of these attacks across 2020 — even after loyalist sources had confirmed the identities of those killed — is somewhat surprising. In other contexts, such as West Africa, the Islamic State regularly claims operations that occurred months earlier, so this absence of retrospective reporting from Syria does not appear to be due to a blanket internal editorial policy on the part of the Central Media Diwan.25

3.4 Location of Attacks

Figure 4 (below) visualizes how the Islamic State’s attacks were distributed across the Badia in 2020. Among other things, it shows that there was a much greater degree of geographic variance in the loyalist dataset than there was in the Nashir/Naba dataset. This is demonstrated in the fact that there are far more red clusters (loyalist-reported attacks) on the map than there are blue clusters (Islamic State-claimed attacks).

Notably, nearly half (33) of all the Islamic State-reported attacks in the Nashir/Naba dataset and some 90% of the entirety of its attacks in Homs governorate were described as having occurred “close to Sukhnah.” This concentration around Sukhnah is represented by the largest blue cluster in the center of Figure 4 just northeast of Palmyra. Besides that, the Islamic State reported three other, much lesser hotspots further east in Deir ez-Zor governorate, as well as a smattering of attacks elsewhere. In general, then, its official reporting was characterized by a lack of specificity, one that stood in contrast to the rest of its reports about attacks in Syria in 2020, which were generally more detailed. By contrast, the loyalist dataset speaks to a much greater degree of diversity, with three major hotspots — one near Sukhnah, one just west of Deir ez-Zor city, and one in the southern Raqqa countryside — and a further 10 lesser hotspots dispersed across the rest of the Badia, with dozens of other more isolated attacks being reported elsewhere in remote parts of Hama, Homs, Raqqah, Aleppo, and Deir ez-Zor governorates. The spread of these reports, which are represented in the red clusters on Figure 4, shows that the Islamic State was reported to have been involved in dozens of incidents in places where it was not reporting any activities at all.

Islamic State reporting patterns differ between governorates as well. For example, the group somewhat regularly publishes pictures of the aftermath of attacks along with its claims in eastern Homs, though these pictures are almost exclusively of single vehicles hit by mines or IEDs. In other words, they are low-intensity, common attacks. Meanwhile, although attacks are fairly consistently claimed in eastern Hama and southern Aleppo, pictures here are exceedingly rare. Claims from Deir ez-Zor are less frequent than in any of the above governorates, and pictures are even rarer. Yet, the few pictures that were released from Deir ez-Zor in 2020 were just as likely to relate to small arms attacks as to IEDs. Similarly, the Islamic State almost never claims attacks or publishes pictures from southern Raqqa, but when it does, they exclusively relate to large-scale small arms attacks. Interestingly, the most recent such claim was mis-attributed by the Islamic State to “the Sukhna countryside” in Homs, despite a wide array of reliable sources placing the attack in southwest Raqqa.

The governorate-to-governorate discrepancy in type of media reports gives rise to potential insights into how the Islamic State’s media apparatus operates within central Syria. Consistent post-IED pictures from Homs combined with few text claims of small arms attacks may suggest that the media operatives or cells with connections to the Central Media Diwan are largely centered around IED cells. Mis-attributed locations of attacks may suggest that in such cases there were several layers of communication between the cell carrying out the attack and the Central Media Diwan, furthering indicating that some cells may not have direct connections to, or the technological ability to connect to, the Central Media Diwan.

- Analysis

This study has shown that the Islamic State appears to be under-reporting on the activities of its cells in the central Syrian Badia — and not in a way that one would assume. Instead of overstating their capabilities and exploits, this dynamic has the effect of playing them down.

While the discrepancies noted above relate only to the Badia and not to other parts of Syria, the impact these missing operations have on the Islamic State’s overarching attack metrics in Syria is significant. Given that loyalist sources reported and ascribed 224 otherwise unclaimed attacks in the Badia in 2020 and that the Islamic State reported 582 attacks across the whole of Syria in the same period, if just these unclaimed loyalist-reported Badia operations are added to the national total, they raise it by about a third, from 582 to 806 across 2020.

Given the loyalist dataset relates only to central Syria, it is feasible that the Islamic State is under-reporting in other parts of the country as well, although as noted, it is reported to be claiming most of its attacks in northeast Syria. Even if it is not, though, the Badia statistics alone are sufficient cause for an adjustment of prevailing threat assessments regarding the remnants of the Islamic State in Syria today.

To be sure, the datasets on which these findings are based have their limitations, and as a result, they must be treated with a critical eye. However, as is known from other studies on Islamic State reporting behavior, including those conducted by the U.S. Department of Defense, its claims have rung truer than is usually assumed to be the case, and these days at least, it does not appear to be in the habit of entirely fabricating kinetic incidents.26 Moreover, for reasons discussed above, loyalist sources are more likely to downplay attacks than exaggerate them. Indeed, the authors ascertained, based on interviews with regime soldiers, that even more attacks hit the regime military and its allies in the Badia in 2020 than were claimed by the Islamic State or publicly reported by loyalists.27

In attempting to determine what is behind this discrepancy between what the Islamic State claimed versus what its enemies reported, which has continued into 2021, the authors have identified six hypotheses, some of which they assess to be more likely than others. The first three address assumptions that the additional 224 loyalist-reported attacks were incorrectly attributed to the Islamic State.

Hypothesis 1: Criminal gangs or other anti-regime elements, not the Islamic State, are responsible

This hypothesis assumes that the Islamic State claims all, or at least most, of its attacks in central Syria. On that basis, some other group (or groups) must be responsible for the more than 200 additional attacks that were attributed to it by loyalists. There are two options for who could be responsible: i) criminal gangs; or ii) anti-regime factions.

To be sure, several criminal organizations operate in the Badia, and on occasion, they have been known to carry out attacks against civilians and regime forces. However, these groups mainly operate in parts of eastern Hama and the Raqqa-Aleppo border region where there are large urban populations and trade to prey on; such networks have few incentives to operate in eastern rural Homs or the Deir ez-Zor desert, from which many of these Islamic State-attributed attacks are being reported by loyalists. When it comes to the few anti-regime forces operating in the Badia, like Kata’ib Sharqiyyah, these groups are so inactive that, even if some of their attacks were misattributed to the Islamic State, this would not have a statistically significant impact on the data. Moreover, the Facebook pages on which much of the loyalist dataset was based routinely differentiate between attacks that are carried out by known Islamic State cells and attacks that are carried out by “unknown individuals.” Finally, repeated interviews with both regime and pro-regime soldiers and SDF officials continually point to the Islamic State as the perpetrator of these attacks.

On that basis, while there could be overlap between attacks perpetrated by criminals and attacks instigated by the Islamic State, the authors believe that it is highly implausible that the majority or even a significant minority of these attacks have been misattributed.

Hypothesis 2: Iran-backed militias, not the Islamic State, are responsible

This hypothesis also assumes that the Islamic State claims all, or at least most, of its attacks in central Syria, and that additional attacks perpetrated by Iranian and Iran-backed militias are being wrongly ascribed to the Islamic State on account of their being false-flag operations. This argument, which a number of Syrian news sources have promoted,28 holds that many, if not most, of these attacks — especially those targeting civilians — are being committed not by the Islamic State but by Iran-backed militias, which are engaging in deceptive operations to give themselves a pretext to remain in Syria.

This scenario seems unlikely for two reasons. First, the principal targets of most of the loyalist-reported attacks are forces that work alongside Iran-backed militias, not civilians. Second, these attacks make sense, from a strategic perspective, for the Islamic State, so it is not just “mindless violence,” as these reports often claim. Raids against civilians often result in the capture of basic goods and sustenance — a critical supply chain for a covert network — and has increased internally displaced people (IDP) flows into northeast Syria, making it easier for the Islamic State to move its own fighters across the informal border between regime- and SDF-held territories.29 Moreover, killing livestock and shepherds in the mountains and steppes of the Badia helps keep locals out of areas the Islamic State cells favors for stashing weapons and moving between positions, something that is also an upshot of its riddling the land with IEDs to deny access to security forces.

Hypothesis 3: Loyalists are over-reporting

Like the first two, this hypothesis assumes that the Islamic State claims all, or at least most, of its attacks in the Badia, and that loyalist sources are fabricating the rest of the attacks they are attributing to it. To be sure, while loyalist sources are just as likely to peddle false information as any other militant actor in Syria, the type of lies pushed by pro-regime accounts revolve around downplaying their own losses and exaggerating Islamic State losses during regime army-led anti-Islamic State operations. Moreover, while rare, at times certain loyalist pages will make up fake reports of fighting in the Badia. However, such reports are easy to distinguish from verifiable claims due to their wording and specificity, as explained in the above methodology section.

Due to the first author’s awareness of these reporting pitfalls, it was possible to sift through loyalist social media and only collect credible news on security incidents. False reports of “fierce fighting” between the army and the Islamic State gained traction on pages about once or twice a month and were always discarded.

Moreover, it is important to note that even if fabricated incidents are included, the loyalist dataset as a whole is still likely to comprise an undercount of the full spectrum of violent activities in the Badia due to the various factors outlined in the methodology section. Some might assume that loyalist sources would exaggerate the level of violence in the region in order to legitimize their presence there. However, such a tactic would be aimed at international audiences, not domestic loyalist communities. As stated in the methodology, the loyalist Facebook pages used to build the second dataset serve as domestic, often hyper-local news sources. They are used to mourn losses among the community and pressure local officials when the security situation degrades too far. As Suhail al-Ghazi told the authors, this desire is at odds with the “regime repeatedly cracking down on individuals who publish ‘harmful’ news,” which pressures communities not to report on Islamic State attacks in the Badia.30

Accordingly, based on the quality of the data, the variance of the sources, and the evidence that was presented alongside each report, it is infeasible that over-reporting could be taking place at this scale, at least per the data points included in the loyalist dataset. Moreover, as mentioned, the trends indicated in this data have been repeatedly supported in interviews with both pro-regime soldiers and SDF officials.

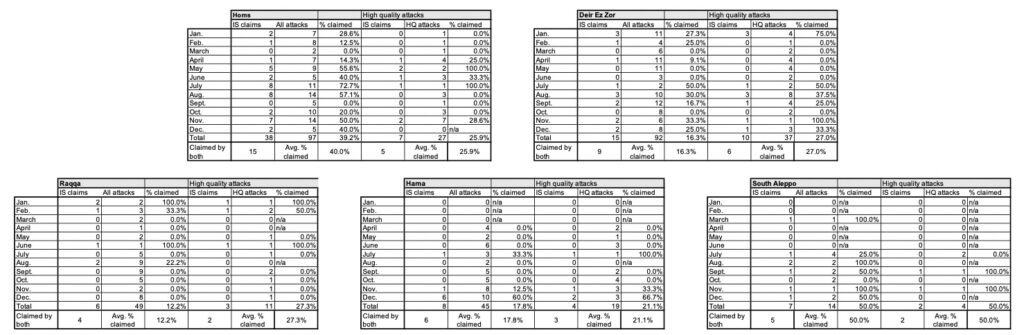

The next three hypotheses assume that the Islamic State did not claim all its attacks in the Badia and that the 224 additional loyalist-reported attacks discussed in this study were in fact perpetrated by it, not some other group or faction. There are three possible explanations for this, none of which are mutually exclusive: i) the Islamic State is intentionally not claiming attacks in order to limit awareness of its activities in this part of Syria; ii) the cells carrying out these attacks have difficulty establishing communication lines with the Islamic State’s Central Media Diwan, meaning they cannot regularly send information or media files relating details of their operations; and/or iii) the structure and consequent priorities of each cell is impacting their appetite or ability for engagement with the Islamic State’s central command in Syria. These hypotheses reference the data in Figure 5 (below).

Hypothesis 4: Strategic silence on the part of the Islamic State

This hypothesis assumes that the Islamic State does not claim all, or even most, of its attacks in central Syria. One reason for this could be that it is seeking to misdirect its adversaries’ attention away from the Badia with a view to giving itself more space to consolidate there. If the region is, say, to operate as a rear base for the Islamic State’s broader network across Syria, it is conceivable that it would engage in deterrence-based violence there without overly publicizing or glorifying it. This would be one way to attempt to avoid drawing undue attention to the area, which, as somewhere that is largely made up of sparsely populated, remote, and hard-to-navigate terrain, is in many ways an ideal territory for a covert network to bed down.

This hypothesis is supported by irregularities in how the Islamic State reported from certain parts of the Badia across 2020. Its activities in Raqqa governorate may be the best example. The remote southern part of governorate, a largely desert area with sparsely populated villages, has endured sporadic Islamic State activity ever since it was officially recaptured from the group in September 2017. However, the Islamic State’s first official claim from the region did not come until January 2020 (i.e., more than two years later). Moreover, the Islamic State only claimed six of the 49 attacks attributed to it by loyalists in southern Raqqa in all of 2020, with a noticeable drop in claims as the year went on. The authors assess this region to serve as a vital transportation node for Islamic State fighters and supplies moving between northeastern and central Syria, and therefore the drop in claims may indicate a conscious effort from the group to not draw attention to its activities there.

Hypothesis 5: Communication difficulties

This hypothesis also assumes that the Islamic State did not claim all, or even most, of its attacks in central Syria. Another reason besides deliberate, strategically motivated misdirection could be that its central Syrian cells are not able to access stable communications between their remote fronts and the Central Media Diwan — after all, the Badia is known to have poor internet and cellular service access.

If Islamic State cells are operating covertly in isolated areas using weapons caches and material sustenance hidden away months, if not years, ago, they may not have the means or inclination to stay in regular contact with its central media apparatus. Moreover, using regime-administered communications infrastructure comes with risks and, even if some cells have access to satellite telephones, this may still be perceived as too dangerous, a factor which would likely end up driving down reporting from the area.

Similar to the above, this hypothesis is also supported by irregularities in how the Islamic State reported from the Badia across 2020. Consider, for example, its relative silence in eastern Homs governorate in the first four months of the year. Between January and April, it claimed only four attacks there despite loyalist sources attributing some 24 attacks to it. In May, Islamic State claim rates increased sharply, with it claiming an average of 41% of its attributed attacks in the governorate across each of the seven following months (the one exception being September, when it claimed none of the five loyalist-attributed attacks). This sudden shift in the Islamic State’s claiming behaviors in eastern Homs, which appeared to coincide with an expansion in geographic reach, may be due to technical difficulties its cells faced in the first third of the year.

Hypothesis 6: Organizational fragmentation/splintering

In line with the above two hypotheses, this one also assumes that the Islamic State does not claim all, or even most, of its attacks in central Syria. While poor communications may be a partial driver of its under-reporting, it seems unlikely that they would account for all of it. After all, there is ample evidence to suggest that Russian-speaking Islamic State fighters based in the Badia are in regular communications with the outside world. In the first few months of 2021, for example, several unofficial videos have emerged, one showing Islamic State training camps in southern Homs area and another eulogizing a Tajik fighter killed in Russian airstrikes in April 2021.31 The fact that there is at least some communication with the outside world suggests that, while lack of telecommunications services may be a factor for some parts of the Badia, other issues are likely at play as well.

Another potential cause is that patterns in Islamic State attack reporting are influenced by the particular structure of the array of cells carrying out these attacks. In the Badia, it is widely known that some Islamic State cells are more locally oriented — commanded and staffed by men from the same countryside in which they are conducting operations — while others have a higher concentration of foreign fighters. There is a chance that some have fewer or less direct connections with the Islamic State’s central media apparatus, while others have stronger connections. This hypothesis is difficult to test, given how sparse details on cell structure are.

However, based on the existence of unofficial videos (the production of which has been strictly forbidden by the Islamic State’s Central Media Diwan since as far back as 201432) and irregularities in Badia reporting, it does seem at least partially feasible. For example, the aforementioned mass kidnapping in eastern Hama was known to have been committed by a group of local Islamic State fighters. (This is known because they exchanged the hostages for family members held by the regime in nearby prisons.) At least one other major cell in eastern Hama is believed by loyalist forces to be formed around local, Hama-based fighters. Given that both of these cells operate in one of the most underclaimed governorates of the Badia, wherein the Islamic State has only reported on 17% of attacks attributed to it, it seems plausible that they are less directly connected with the organization’s core (perhaps on account of their more parochial activities or the location[s] in which they operate).

- Conclusion

Taking into account the full extent of the data and weighing up each of the abovementioned hypotheses, it seems clear that the Islamic State was systematically under-reporting on its activities in the central Syrian Badia in 2020. Indeed, based on the data presented above, the Islamic State claimed only 25% of its Badia attacks in 2020, a trend which has continued throughout the first half of 2021.33

However, the rate of both Islamic State attacks and claims dropped significantly beginning in July 2021, when the group claimed only three of at least 21 attacks in central Syria. In August, Islamic State fighters claimed none of their at least 10 attacks, the first month without claims in this region since 2019. This sharp drop in official claims comes amid intense, continuous regime operations that have seen Islamic State cells displaced across the Badia, particularly in Deir ez-Zor and Homs during the spring and in Hama during June and July. Together, this suggests that the current degree of under-claiming is more likely caused by broken communication lines and cells shifting to “survival mode” than by intentional misdirection.

Analyzed solely through its own reporting, the Islamic State’s capabilities in the Badia seem sophisticated but sporadic. Yet when its loyalist-reported attacks are factored in, the group appears to be far more powerful in the region than it has let on. Based on this dynamic, which is almost certainly driven by multiple factors but is likely due at least partially to deliberate misdirection from the Central Media Diwan, the authors assess that the group could be developing a large portion of this terrain into a secure rear base from which to train new recruits, hide covert networks, and base commanders who can remotely coordinate campaigns in its environs and beyond.34

In fact, an entire page of the Aug. 12, 2021 edition of the Islamic State’s weekly Al Naba editorial was devoted to praising the insurgents in central Syria, comparing them to the original Islamic State in Iraq insurgents in the mid-2000s and bragging about the “military bases and legal schools” that have been established in the Badia.

Recent analyses of global Islamic State activities have noted that the group is increasingly tacking toward Africa, where its affiliates have been conducting brazen daytime takeovers of towns and bases in places such as Nigeria and Mozambique. While this may be the case, it is important to recognize that the Islamic State may be intentionally diverting attention away from its historic heartlands in Iraq and Syria. After all, as long as the U.S.-led global coalition remains in these states, it has few prospects of being able to take control of and ultimately govern urban centers again. On this basis, it is critical that policymakers account for the possibility that it is using the success of its affiliates abroad to distract from the slow, methodical groundwork it is laying in Syria for a future resurgence.