Is the term accurately a descriptive for Iran’s far-right extremist theocratic leaders, or is it used to whitewash and excuse Iran’s politics?

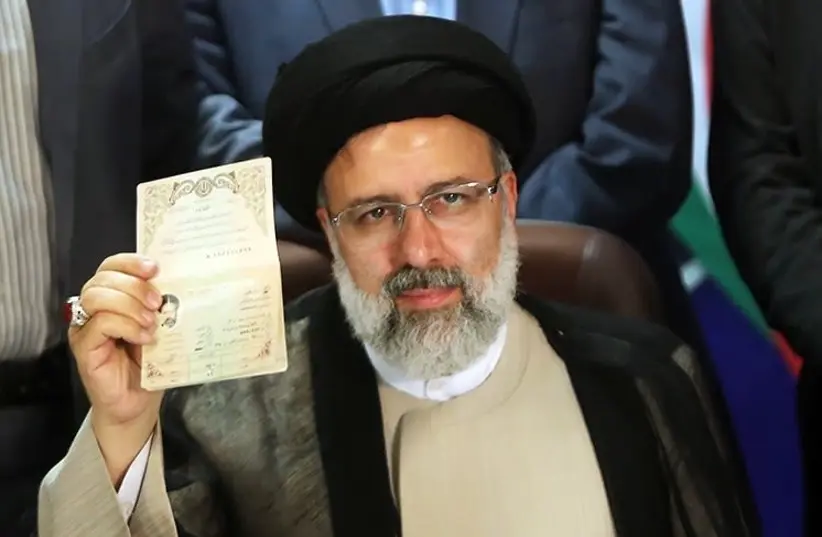

A global narrative present in major media outlets uses the term “hardliner” to describe Ebrahim Raisi, the winner of Iran’s presidential election on Saturday.

The term “hardliner” was invented to describe the far-right in Iran – it is generally not used to describe any other form of politics in the world. For instance, Israel, Saudi Arabia, Malaysia, Japan, Spain or the Congo don’t have “hardliners” – only Iran does.

Does the term accurately describe Iran’s far-right extremist theocratic leaders, or is it used to whitewash and excuse Iran’s politics, the way “militants” is used to describe extremist groups that mass murder civilians?

Major media outlets and figures that have used the term “hardliner” also explain to the readers what it means, but only sometimes.

The BBC noted that “Iran’s hardliners will seek to reinforce a puritanical system of Islamic government, possibly meaning more controls on social activities, fewer freedoms and jobs for women, and tighter control of social media and the press. The hardliners are suspicious of the West, but both Raisi and Supreme Leader Khamenei favor a return to an international deal on Iran’s nuclear activity.”

BBC’s headline on June 19 was that “hardliner Raisi will become president.”

CNN also called Raisi is the “hardliner” who will be the next president. However, CNN’s headline also calls him “ultraconservative.”

The article noted that “From 2018 onwards, [former President Donald] Trump unleashed a torrent of sanctions that crippled Iran’s economy and emboldened hardliners. The tiny window of opportunity granted by the clerical class to the moderate government of President Rouhani to engage with the US and Europe began to quickly close. Trump had proven the hardliners’ skepticism about the West correct, Iran’s conservatives repeatedly said.”

According to France24, Raisi is an “ultra-conservative” who is replacing a “reformist” in the current President Hassan Rouhani. Under Rouhani, women were persecuted for not covering their hair, for protesting, and for other minor offenses. A well-known wrestler was murdered under Rouhani’s supposed “reform” leadership. Foreign tourists were kidnapped and kept in prison. Journalists and dissidents were hunted down abroad. CBS also calls Raisi a hardliner, as does Turkey’s TRT.

With the term “hardliner” cemented as the only normative term that can be used to describe Raisi, it is worth wondering what else is going on.

Is there any substantial difference between the Islamic regime under the “hardliners” than under the “reformers”?

IRAN ALLOWS some diversity of thought. Its media has more interesting stories than the totally totalitarian media in Turkey, where only pro-AKP views are aired on state media and where criticism of the president can land people in prison.

Iran’s regime is more open than the regimes Iran supports in Damascus and the thugs it supports among Hezbollah and the Houthis, as well as militias in Iraq.

However, Raisi may be even worse than what Iran has seen in the past. On June 19, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch said that “Ebrahim Raisi’s election as Iran’s new president was a blow for human rights and called for him to be investigated over his role in what Washington and rights groups have called the extrajudicial executions of thousands of political prisoners in 1988,” according to Reuters.

It looks like Raisi is not just a “hardliner” or “conservative” but was responsible for mass murder. That would put him on par with other murderous regime leaders. Accusations of crimes against humanity are not usual for a ruler of a country.

Amnesty noted that, “in 2018, our organization documented how Ebrahim Raisi had been a member of the ‘death commission’ which forcibly disappeared and extrajudicially executed in secret thousands of political dissidents in Evin and Gohardasht prisons near Tehran in 1988.” This sounds like a lot more than just “hardliner.”

THE REASON the term “hardliner” was invented was largely as a foil for narratives in the West. The Western countries needed the far-right extremist Iranian regime that hangs innocent people to have a good side, so “reformers” were conjured up.

Then “hardliners” were said to oppose them. But the reality was that Iran’s regime, run by Ayatollah Khamenei and the IRGC, was already one of the most extremist regimes in the world.

But Western governments wanted to make a deal with it in the run-up to the 2015 JCPOA. To do this, a narrative was created – through focus groups and various lobbying groups that were close to governments and media – to push narratives about the so-called “Iran Deal” and the need to “empower moderates.”

This created a narrative where anyone opposing the Iran deal was “empowering hardliners” by not giving Iran’s regime everything it wanted.

It didn’t matter if Iranwas imprisoning people and giving them “lashes” for music videos or kidnapping Western tourists and falsely accuse them of spying to use them as hostages – the regime had “moderates” and “hardliners.”

During the Trump era, the narrative worked to portray him as “empowering hardliners.” When the Biden administration came into office, there were attempts to argue that the administration should rush back to the Iran deal or the “hardliners” might win the June elections. Now we have seen the “elections” in which basically only “hardliners” were allowed to run.

It stands to reason that Iran has “hardliners” the way other countries do. Iran doesn’t exist on the moon; its politics are linked to those in Iraq, Lebanon and the rest of the region. It may be the only Shi’ite theocracy, but its version of political Islam is not so different from that of the supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood who run Turkey’s AKP.

It is a “revolutionary” power, but largely in a reactionary way. This leaves many questions as to why it has “hardliners” while other countries often do not, at least consistently the way Iran’s politics is said to be divided.

This brings to mind how Western countries are often said to have a “far right,” much as Israel has a “far right” – while in Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, Pakistan or Malaysia there are fewer references to the “far right.”

This is because Western media often lacks a lexicon to discuss non-Western political systems. In such cases, arbitrary terms like “hardliner” are used. This is in place of local terms.

When it comes to Raisi it’s not clear if the term “hardliner” is enough to describe a man now potentially wanted for crimes against humanity.