Since 2023, Islamic State Sahel Province (IS Sahel), a violent extremist organization affiliated to the Islamic State, has shifted from perpetrating high levels of indiscriminate violence against civilians towards building community support in areas where it has consolidated its influence. It has also begun actively reviving local economies (including illicit activities) that had been heavily undermined by its earlier indiscriminate use of violence.

After almost 10 years of insurgency in the Sahel, the group has made significant territorial gains in the last two years. According to the UN Panel of Experts on Mali, in the year to August 2023 alone it doubled the area it controlled in the country.1 From mid-2022 IS Sahel also started operating beyond the Sahel, including in north-eastern Benin.2

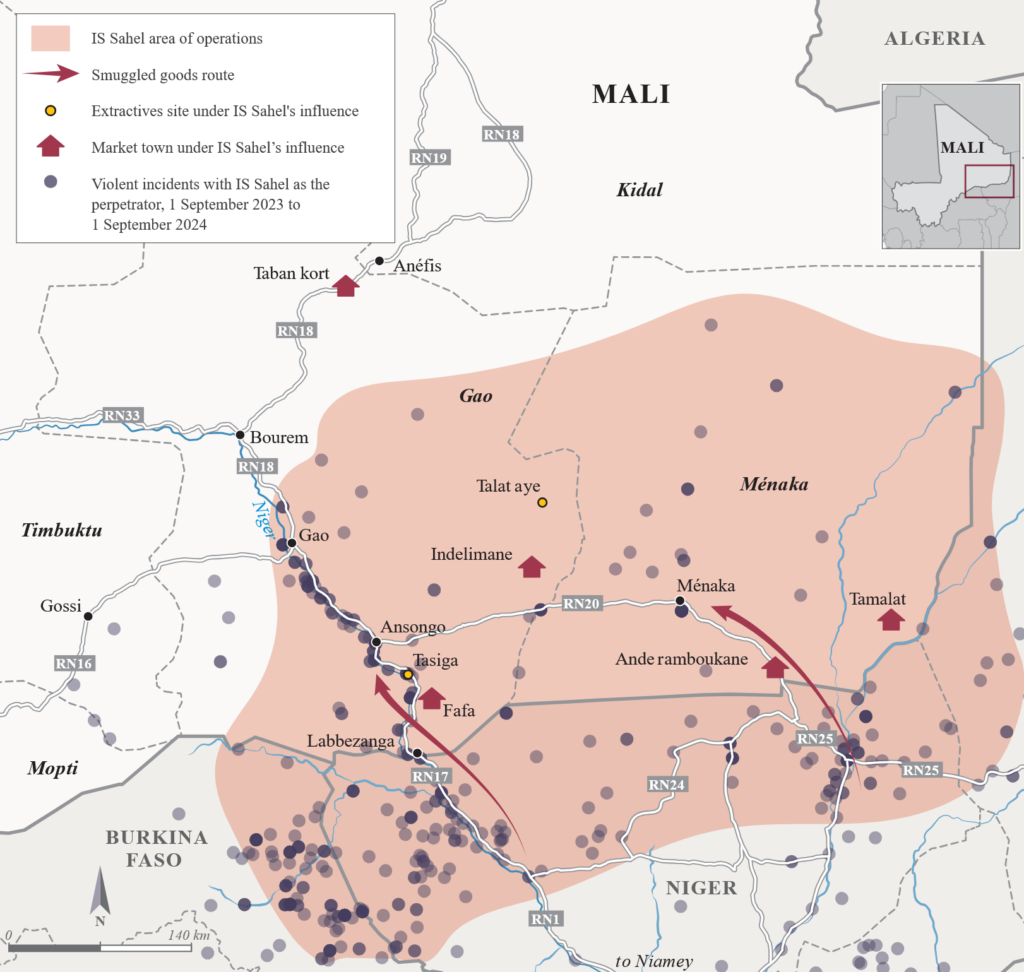

Some of the group’s largest gains have come in north-eastern Mali’s Ménaka region, which it almost entirely controls, except for Ménaka town itself. IS Sahel however controls all the roads leading to and from this town, enabling it to police the movement of people and supplies. The group’s hold over the Ménaka region represents the first time its influence has been uncontested over large swathes of territory.3

IS Sahel’s behavioural shift – away from indiscriminate violence and towards positioning itself as a provider of economic opportunities – has been especially pronounced in Ménaka. This shift in focus is likely to earn the group a degree of local legitimacy, while also enabling it to exploit and profit from related economic opportunities, both licit and illicit.

Figure 1 IS Sahel’s zone of control and main smuggling routes.

Territorial control enables violence reduction

Established in May 2015, IS Sahel had effectively been territorially defeated by the end of 2021, due to military pressure from two very different sources – the French counter-insurgency Operation Barkhane and competition from al-Qaeda-affiliated Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

However, the IS affiliate has since staged a remarkable comeback, returning to the Ménaka region in 2022, capitalizing on France’s military withdrawal that year. IS Sahel’s reliance on high levels of indiscriminate violence during its initial territorial resurgence – alongside looting, extortion, zakat4 and cattle rustling – sparked substantial displacement. This mass displacement left some areas empty, and others peopled only by residents who collaborated with the group and did not pose a threat. These effectively became spaces of compliance, reducing the group’s need to use high levels of violence and opening an opportunity for a more nuanced local strategy.

From early 2023, IS Sahel reduced its use of violence. Civilian fatalities in the Ménaka region in the first seven months of 2024 were eight times lower than during the same period in 2022 (66 and 525 respectively).5 Only three cattle rustling incidents were recorded in the seven months to August 2024, a dramatic decline from the thousands of cattle stolen in 2022.6

Not only the scale, but the nature of violence used by the group changed. IS Sahel largely leveraged violence more discriminately, although some seemingly random attacks on villages and thefts of herd persisted. The use of violence is now mostly driven by two clear purposes: the punishment of perceived traitors and the exertion of control over goods transiting its territory. Violence therefore tends to target communities perceived by IS Sahel as allied with pro-government groups, notably the Dawsahak community. Meanwhile, territorial control is consolidated by arresting the drivers of vehicles and seizing (or even burning) goods that IS Sahel has not cleared for passage (or taxed accordingly).

This correlation between increasingly uncontested territorial control and decreased violence is in line with broader patterns tracked by analysts monitoring armed group activity.7 Comparing IS Sahel’s behaviour towards civilians in Ménaka and Gao – a neighbouring region to the west of Ménaka – is telling. In the Gao region, IS Sahel has significantly expanded its influence over the last two years, including in Ansongo district, and across key roads, including the route between Gao and Niamey, the capital of neighbouring Niger. However, IS Sahel faces competition from JNIM, pro-government militias, and the Malian armed forces and their Russian partners in the Wagner Group (now rebranded as the Africa Corps).

In the first seven months of 2024, the number of violent incidents against civilians perpetrated by IS Sahel was almost 10 times higher in the Gao region (65 incidents in total) than in the Ménaka region (seven incidents), despite IS Sahel’s presence being spread much wider geographically in the Ménaka region.8 IS Sahel‘s behavioural shifts in Ménaka thus appear to have been shaped by the consolidated control it has established in the region.9

Economic revival consolidates territorial control

From early 2023, IS Sahel started engaging in conventional economic activity in the Ménaka region, for two main reasons. First, the group needed to revive supply chains and the local economy, which had collapsed following its 2022 offensive, in order to replenish its own resources. Second, it recognized that long-term territorial control would be best achieved by fostering positive relationships with local communities. By positioning itself as a provider of livelihoods and actively involving itself in critical local economies (notably gold mining and goods smuggling), the group has sought to burnish its governance credentials.

To encourage communities to return, IS Sahel launched efforts to win their trust. Between March and July 2023, it distributed leaflets, preached in mosques and used platforms including WhatsApp and Al-Naba to communicate its methods and values.10 Promising protection, IS Sahel invited displaced communities to resettle in its territories – a pledge given some credence by its elimination of local resistance.

Although initially hesitant, some communities gradually returned. As livestock is vital for survival in rural areas, IS Sahel returned animals it had previously stolen, including to communities north-east of Ménaka in May 2023.11 It also invested in rebuilding infrastructure, including houses and water points.12

Additionally, the group’s moral police, known as the Hisba, launched campaigns against crime, arresting non-affiliated bandits and criminals. In one case, in July 2023 in Anderamboukane, IS Sahel members amputated the hands and feet of two youths at a market for extorting taxes in the group’s name.13

Territorial control boosts revenues

IS Sahel also focused on reviving economic connections and supply routes between Mali and Niger, with links extending to Nigeria. The group collaborated with traders, providing them with vehicles and mandating them to supply open air markets, the economic hubs of rural north-eastern Mali. Markets in Tabankort, Tamalat, Indelimane, Fafa and Anderamboukane consequently received goods including fuel, motorbikes, food and medicine, mostly smuggled across borders.14

The reliance on goods from Niger and Algeria increased after Gao and Ménaka were cut off from southern Mali due to a JNIM blockade that began in June 2023 in Boni on the national road linking Mopti to Gao. These efforts not only ensured the group’s access to key goods but also reinforced its role as an economic facilitator for traders and communities under its control.

Traders that are not directly associated with IS Sahel as described above need to pay the group to access territories (or use stretches of road) that it controls. A trader who transports goods along the Gao-Niamey route told the GI-TOC: ‘No commercial truck or bus can do this route without having previously agreed with IS Sahel, which in this zone is under the leadership of Moussa Moumouni.’15

Regional bus companies operating between Niamey and Gao – a route often used by West African migrants travelling to work in artisanal gold mines in the Gao and Kidal regions, or beyond – confirmed these arrangements, but they were reluctant to share details.16 Sources revealed that these bus companies typically paid a monthly fee of around 500 000 CFA francs (FCFA), equating to €762, or a quarterly fee of FCFA1.2 million (€1 829) to use the road.17 Various fees for trucks carrying commercial goods were reported, but could not be independently verified by the GI-TOC.

IS Sahel has consolidated its influence over artisanal gold mines in the Ménaka and Gao regions, around Talataye (north-east of the town of Gao) and in the Ansongo district (south of Gao). The group has also been in control of a manganese site in Tassiga since late 2022.18 IS Sahel does not operate the mine itself, nor does it regulate activity around the mine heavily (unlike other armed groups). However, it controls the roads and access to mines, imposes a tax on miners in exchange for protection, and prohibits weapons on the sites.19

While to date IS Sahel’s behavioural shift seems closely tied to the degree of control it exerts over territory, there are some indications that the group is applying amended approaches in more contested areas. One key example is northern Benin, where it appears to be building relationships with communities and positioning itself as a provider of economic opportunities.

For now, evidence of IS Sahel’s involvement in economic activities in Benin centres on the department of Alibori and remains largely anecdotal. The group is reportedly buying small boats (pirogues) for traders who smuggle goods across the Niger River into Niger, alongside funding phone credit for these traders.20 Additionally, IS Sahel has been taxing communities to access Benin’s W National Park, and the group also collects zakat.21 However, no taxation of illicit or contraband goods has been identified in Benin.22

Benin’s Alibori department therefore appears poised to become a priority area for IS Sahel operations. The group’s engagement is driven in part by a desire to present itself as a credible alternative to JNIM,23 in part because the opportunities W National Park offers as a hideout for launching attacks. Other motives include positioning itself as a provider of livelihoods to communities and the opportunity to secure new sources of revenues and resources.24

Lastly, Alibori could also serve as a stepping stone for IS Sahel to link itself with another IS branch, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), since this department borders Nigeria, where ISWAP is based. This potential link-up creates a clear risk of a further regional resurgence of jihadist activity.25

Conclusion: hearts and minds in Benin?

In capitalizing on the security vacuum generated by France’s military withdrawal from Mali, IS Sahel appears to have learned valuable lessons from a decade of very mixed fortunes in the region. The last year has seen a marked pivot in its relationship with key communities and in its approach to revenue generation.

As the jihadist group turns its attention increasingly towards Benin, one key factor to watch will be the extent to which it applies the softened playbook that it has already used to significant effect in Mali. It will be especially interesting to see how far IS Sahel seeks to build legitimacy among communities in areas where its territorial control is not yet cemented. If the group’s continued territorial expansion is accompanied by a further reduction in its reliance on violence in favour of relationship building, this would signal a medium- to long-term shift in strategy, likely facilitating its regional durability.

Notes

United Nations Security Council (UNSC), Final report of the Panel of Experts on Mali, August 2023. ↩

Clingendael, Conflict in the Penta-Border area: Explaining ISGS activity in Benin, December 2022. ↩

There are no other armed groups that pose a threat to IS Sahel and operations by the armed forces against the group are rare. ↩

Zakat, when applied legitimately, is a charitable donation required of Muslims, ostensibly to fund support for the poor. ↩

Armed Conflict Location and Event Data (ACLED). ↩

According to data from ACLED. ↩

ACLED, Gang violence: Concepts, benchmarks and coding rules, February 2023; Héni Nsaibia, Insecurity in southwestern Burkina Faso in the context of an expanding insurgency, ACLED, 17 January 2019; ACLED & GI-TOC, Non-state armed groups and illicit economies in West Africa: JNIM, 18 October 2023; Vanda Felbab-Brown, Harold Trinkunas and Shadi Hamid, Local Orders in an Age of International Disorder, Militants, Criminals and Warlords, Taylor & Francis, 2017. ↩

According to data from ACLED. ↩

Royal United Services Institute, Protecting civilians as strategy: Supporting a conflict sensitive response to the strategic challenge of ‘jihadist’ armed groups in the wider Sahel, June 2024; Dans le nord-est du Mali, l’Etat islamique en voie de normalisation, Afrique XXI, 13 November 2023. ↩

See for example the IS pamphlet ‘This is our dogma and this is our method’, shared by Wassim Nassr on X. ↩

Dans le nord-est du Mali, l’Etat islamique en voie de normalisation, Afrique XXI, 13 November 2023. ↩

Ibid. Water points were rehabilitated in Tajalalt, Tabankort, Inchinane, Tamalat and Aghazraghan. ↩

According to data from ACLED. ↩

Interview with a businessperson, Ménaka region, July 2024. ↩

Interview with a transporter in Gao, March 2023. Information confirmed remotely in July 2024. ↩

Field interview with representatives of two transport companies (unnamed for security reasons), March 2023. Information confirmed remotely in July 2024. ↩

Field interview with several transporters who operate along the Niamey-Gao road, March 2023. Information confirmed remotely in July 2024. ↩

UNSC, Final report of the Panel of Experts on Mali, August 2023. ↩

Field interview with gold miners, Gao, July 2024. ↩

Interview with an expert, northern Benin, July 2024. ↩

Until 2023, IS Sahel was demanding one out of every 10 cattle; however, it increased this to two out of every 10 cattle in 2024. Remote interviews with herders, Alibori, July 2024. ↩

Eleanor Beevor et al, Reserve assets: Armed groups and conflict economies in the national parks of Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin, GI-TOC, May 2023. ↩

Clingendael, Conflict in the Penta-Border area: Explaining ISGS activity in Benin, December 2022. ↩

Eleanor Beevor et al, Reserve assets: Armed groups and conflict economies in the national parks of Burkina Faso, Niger and Benin, GI-TOC, May 2023. ↩

Clingendael, Dangerous liaisons: Exploring the risk of violent extremism along the border between northern Benin and Nigeria, June 2024. ↩