A visit by the commander of Iran’s elite Quds Force to Baghdad has led to a pause in attacks on U.S. troops by Iran-aligned groups in Iraq, multiple Iranian and Iraqi sources told Reuters, saying it was a sign Tehran wants to prevent a broader conflict.

Esmail Qaani met representatives of several of the armed groups in Baghdad airport on Jan. 29, less than 48 hours after Washington blamed the groups for the killing of three U.S. soldiers at the Tower 22 outpost in Jordan, the sources said.

Qaani, whose predecessor was killed by a U.S. drone near the same airport four years ago, told the factions that drawing American blood risked a heavy U.S. response, 10 of the sources said.

He said the militias should lie low, to avoid U.S. strikes on their senior commanders, destruction of key infrastructure or even a direct retaliation against Iran, the sources said.

While one faction did not initially agree to Qaani’s request, most others did. The next day, elite Iran-backed group Kataib Hezbollah announced it was suspending attacks.

Since Feb. 4 there have been no attacks on U.S. forces in Iraq and Syria, compared to more than 20 in the two weeks before Qaani’s visit, part of a surge in violence from the groups in opposition to Israel’s war in Gaza.

“Without Qaani’s direct intervention it would have been impossible to convince Kataib Hezbollah to halt its military operations to deescalate the tension”, a senior commander in one of the Iran-aligned Iraqi armed groups said.

Qaani and the Quds Force, the arm of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards that works with allied armed groups from Lebanon to Yemen, did not immediately reply to requests for comment for this story. Kataib Hezbollah and one other group could not be reached for comment. The U.S. White House and Pentagon also did not immediately respond.

Qaani’s visit has been mentioned in Iraqi media but the details of his message and the impact on reducing attacks have not been previously reported.

For this account, Reuters talked to three Iranian officials, a senior Iraqi security official, three Iraqi Shi’ite politicians, four sources in Iran-backed Iraqi armed groups and four Iraq-focused diplomats.

IRAQ-U.S. TALKS RESUME

The apparent success of the visit highlights the influence Iran wields with Iraqi armed groups, who alternate between building pressure and cooling tensions to further their goal of pushing U.S. forces out of Iraq.

The government in Baghdad, a rare ally of both Tehran and Washington, is trying to prevent the country again becoming a battlefield for foreign powers and asked Iran to help rein in the groups after the Jordan attack, five of the sources said.

Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani “has worked with all relevant parties both inside and outside Iraq, warning them,” that escalation “will destabilise Iraq and the region,” Sudani’s foreign affairs advisor Farhad Alaadin told Reuters when asked to confirm Qaani’s visit and the request for help to rein in armed groups.

The attack “played into the hand of the Iraqi government.” a Shi’ite politician from the ruling coalition said. Following the subsequent lull in hostilities, on Feb. 6 talks resumed with the United States about ending the U.S. presence in Iraq.

Several Iran-aligned parties and armed groups in Iraq also prefer talks rather than attacks to end the U.S. troop presence. Washington has been unwilling to negotiate a change to its military posture under fire, concerned it would embolden Iran.

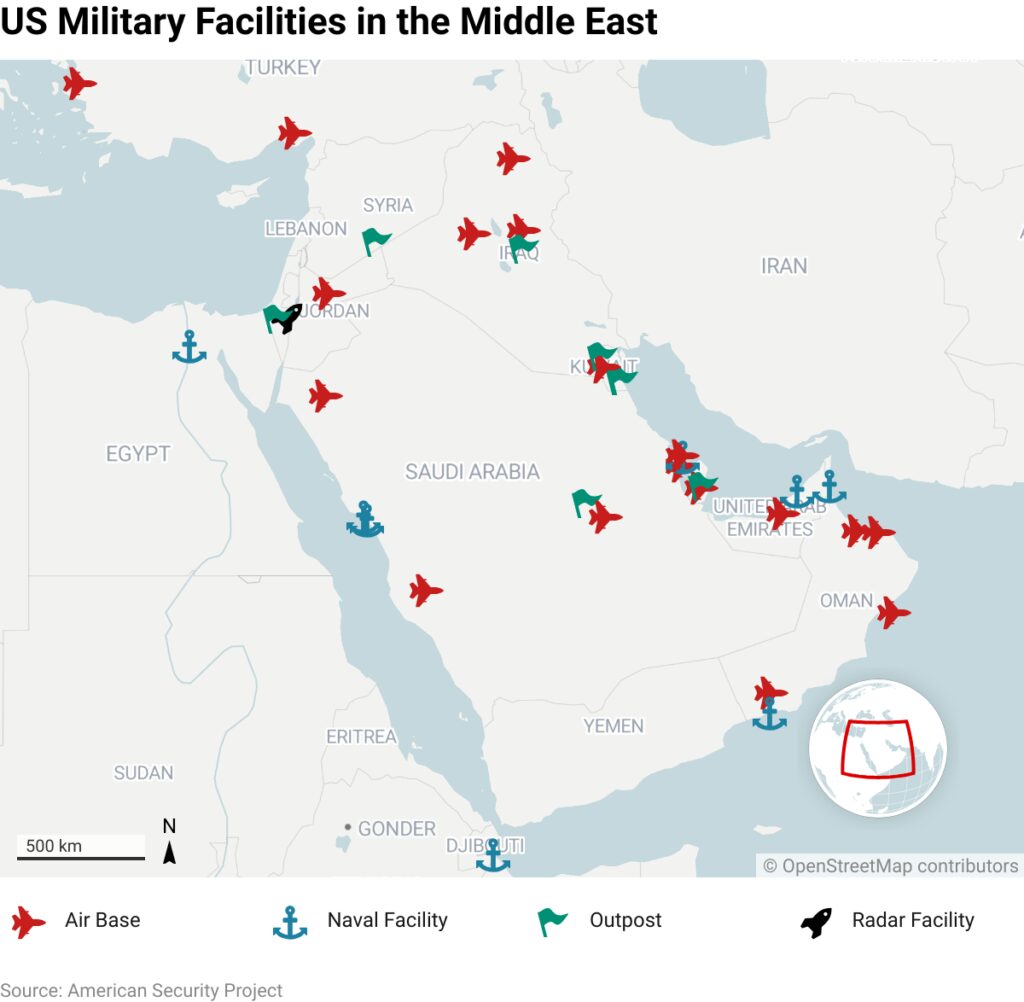

The United States currently has some 2,500 troops in Iraq and 900 in Syria on an advise and assist mission. They are part of an international coalition deployed in 2014 to fight Islamic State, mainly in the west of the country and eastern Syria.

A U.S. State Department spokesperson, who declined to comment on Qaani’s visit to Baghdad, said the U.S. presence in Iraq would transition to “an enduring bilateral security relationship.”

The United States asserts that Iran has a high level of control over what it calls Iranian “proxies” in the region. Tehran says it has funded, advised and trained allies but they decide operations on their own.

Another U.S. official recognised Iran’s role in reducing attacks but said it was not clear if the lull would hold.

“We need to see more work done on the ground,” by Iraq to control the militias, a separate, senior, U.S. official said, noting just a few arrests were made after a December mortar attack on the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.

AIRPORT SECURITY

With Iran bracing for a U.S. response to the Jordan attack, Qaani made the visit quick and did not leave the airport, “for strict security reasons and fearing for his safety,” the senior Iraqi security source said.

The strike in 2020 that killed former Quds Force leader Qassem Soleimani outside the airport followed an attack Washington also blamed on Kataib Hezbollah that killed a U.S. contractor, and at the time sparked fears of a regional war. Along with Soleimani, the drone killed former Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis.

Both Tehran and Baghdad wanted to avoid a similar escalation this time round, nine sources said.

“The Iranians learned their lesson from the liquidation of Soleimani and did not want this to be repeated,” the senior Iraqi security source said.

A high-ranking Iranian security official said: “Commander Qaani’s visit was successful, though not entirely, as not all Iraqi groups consented to de-escalate.” One smaller but very active group, Nujaba, said it would continue attacks, arguing that U.S. forces would only leave by force.

It remains to be seen how long the pause holds. An umbrella group representing hardline factions vowed to resume operations in the wake of the U.S. killing of senior Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Baqir al-Saadi in Baghdad on Feb. 7.

Saadi was also a member of the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF), a state security agency that started out as mostly-Shi’ite armed groups close to Iran that fought against Islamic State, highlighting just how intertwined the Iran-backed armed groups are with the Iraqi state.

U.S.-led forces invaded Iraq and toppled former leader Saddam Hussein in 2003, before withdrawing in 2011.

Shi’ite armed groups who spent years attacking U.S. forces in the wake of the 2003 invasion went on to fight on the same side as, though not in direct partnership with, U.S. soldiers against Islamic State until it was territorially defeated.

In the subsequent years, rounds of tit-for-tat fighting with the remaining U.S. troops escalated until the U.S. killing of Soleimani and Muhandis.

Those killings prompted Iraq’s parliament to vote for the exit of foreign forces. Prime Minister Sudani’s government came to power in October 2022 on a promise to implement that decision, though it was not seen as a priority, government officials have said.

The situation changed again with the onset of the Gaza war.

Dozens of attacks and several rounds of U.S. responses, including the killing of a senior Nujaba leader in Baghdad on Jan. 5, led Sudani to declare that the coalition had become a magnet for instability and to initiate talks for its end.

He has kept the door open to continued U.S. presence in a different format via a bilateral deal.

Iraqi officials have said they hope the current lull will hold so the talks, expected to take months if not longer, can reach a conclusion.

At a funeral service for Saadi, senior Kataib Hezbollah official and PMF military chief Abdul Aziz al-Mohammedawi vowed a response for the latest killing, but stopped short of announcing a return to violence. The response would be based on consensus, he said, including with the government.

“Revenge for the martyr Abu Baqir al-Saadi means the exit of all foreign forces from Iraq. We wont accept anything less than that,” he said.