This investigation reveals how Nigeria’s dubious defence contracts gave Hima Aboubakar, a Nigerien arms broker, instant riches.

Amid the spilling of raw emotions over Boko Haram’s shocking kidnapping of 214 Chibok schoolgirls in Borno State, north-east Nigeria, in April 2014, the Nigerian government awarded contracts worth millions of dollars for the supply of weapons and tools to boost its offensive against the terrorists. But before formalising the contracts, officials began transferring millions to the contractor, Hima Aboubakar.

Mr Aboubakar, an arms broker from Niger Republic on Nigeria’s northern border, had no company and bank accounts in Nigeria to execute the defence contracts when he burst onto the scene in 2014, one of the years Boko Haram was most brutal in killing civilians.

Within a month, he incorporated a company with no organisational structure and opened a bank account for the firm, designating himself as the sole signatory. Just seven days later, $36 million from the Nigerian government was deposited into the newly established account, beginning a cash flow spanning 14 months from the Nigerian government into the account and subsequent ones set up by Mr Aboubakar.

In 2015, a probe committee established by then-President Muhammadu Buhari investigated these contracts and others dating back to 2007. The Committee on Audit of Defence Equipment Procurement (CADEP) uncovered “opaque, poorly supervised, irreconcilable, and dubious contracts” awarded to Mr Aboubakar and his firms. More broadly, the committee revealed that the then National Security Adviser, Sambo Dasuki, who disbursed arms contract funds to Mr Aboubakar and other contractors between 2014 and 2015, could not account for $2 billion. Mr Dasuki has denied any wrongdoing and has been on trial since 2015.

PREMIUM TIMES has obtained a trove of previously unreleased court documents shedding light on a scheme that has siphoned Nigeria’s arms funds for decades.

The documents were filed in 2020 at the Federal High Court in Abuja by Nigeria’s leading anti-corruption agency, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), to seek the forfeiture of balances in some of Mr Aboubakar’s bank accounts and properties linked to him in Abuja, while making efforts to arrest him for prosecution. EFCC declared him wanted on 24 October 2019 and, in the following year, began to pursue the non-conviction-based forfeiture proceedings targeting his assets within reach. The case is on appeal after Mr Aboubakar won at the trial court.

Our analysis covered bank records, corporate filings, title documents, house purchase agreements, and extrajudicial statements of parties to the real estate transactions. We cross-referenced these documents with reports of investigative panels and United States court filings relating to ongoing legal battles over part of the arms funds confiscated by the American government.

The review paints a more detailed picture of investigators’ earlier findings of how Mr Aboubakar shortchanged Nigeria by undersupplying military equipment, inflating prices, and dishonestly supplying refurbished equipment that often broke down.

Our report shows how the dubious nature of the contracts precipitated Nigeria’s losses but enriched Mr Aboubakar with millions of dollars.

Scrutinising nearly 1,000 bank transactions across 10 bank accounts connected with Mr Aboubakar shines a clearer spotlight on where a significant amount of the funds went into instead of arms procurement.

The tracking reveals patterns of alarming cash withdrawals and transfers to bureau de change operators from the accounts of Mr Aboubakar’s companies that received payments in dollars from the Nigerian government. On a certain day, Mr Aboubakar withdrew $200,000 in 25 instalments, totalling a staggering $5 million.

These cash transactions and transfers to forex operators, which prosecutors say raise money laundering concerns, were often followed by massive deposits from bureau de change operators in Mr Aboubakar’s personal accounts.

From the personal accounts, Mr Aboubakar bought luxury cars and real estate within and outside Nigeria and transferred funds to military officials who EFCC said were involved in the approval of defence contracts secured by him. EFCC also said several of these cars were distributed to the military officers. Nigerian courts cleared some of the officers of wrongdoing but at least one of them was convicted of receiving bribes from Mr Aboubakar.

Broadly, funds from two corporate dollar accounts moved directly to a few arms vendors. But a larger chunk of them streamed to bank accounts of local and offshore entities with unclear corporate missions, stores, individuals, forex operators, who paid back to Mr Aboubakar’s accounts in different currencies, mostly naira. A significant amount also vanished from the accounts through cash withdrawals.

Mr Aboubakar’s lawyer, Kayode Ajulo, declined to discuss the case, citing his current position as Attorney-General and Commissioner for Justice in Ondo State. However, the lawyer maintained his client’s innocence in a 2020 court filing, where he also declared that Mr Aboubakar had relocated permanently to his country, Niger Republic.

EFCC, too, has yet to respond to our enquiries about the case.

Legacies of corruption

Corruption, underpinned by the general climate of impunity, runs deep in Nigeria’s defence contracting processes and reaches far back in time, contributing to the worsening insecurity.

“The undisputed connections between corruption broadly and insecurity are globally resolved,” said Lanre Suraj, who chairs the Human and Environmental Development Agenda (HEDA), a non-government organisation that has carried out extensive research and led transparency advocacies on public procurement and corruption in the county.

His assertion is consistent with the consensus of several studies.

For instance, a 2020 research revealed a mismatch between funding for Nigeria’s military and its performance. It said “despite huge spending or expenditures on military operations within the years, the security of the state remains deteriorating.” It blamed the outcome on corruption, a lack of transparency in military procurement, the absence of monitoring and control mechanisms, among other issues.

The Nigerian government, through the military and funding institutions, hides under the broad precept of national security to avoid accountability in awarding defence contracts and use of allocated funds.

Under the cloud of secrecy, the provisions of the Public Procurement Act (PPA), 2007, which governs all categories of contracts, are violated.

Procuring authorities abuse the exemptions the PPA grants defence contracts, totally disregarding mandatory safeguarding provisions of the law that seek to ensure the government gets value for its military spending.

CADEP, set up by the Buhari administration in 2015 to probe arms procurements dating back to 2007, concluded that virtually all the Nigerian Army procurement handled by the Ministry of Defence, the Nigerian Army and ONSA “were fundamentally not executed in compliance with the PPA 2007.”

The consequences of the culture of arbitrariness and legal violations regarding defence contracts are dire, but the full scope may never be known.

In January this year, the government of Jersey Island announced the recovery of Nigeria’s $8.9 million looted through phoney defence contracts between 2014 and 2015, highlighting the potential for yet undiscovered arms funds still hidden within and outside Nigeria.

“Defence procurements remain far from being transparent and corruption-free in Nigeria,” Mr Suraj said.

Inside the flawed contracts

Mr Aboubakar, 51, also known as Petit Boubé, rapidly ascended to prominence as an arms broker in Niger, transitioning from a small-time printer to a major supplier of arms to the Niger government within a few years.

His foray into the arms trade began in 2000 when he leveraged connections in the newly formed Mouvement National pour la Société du Développement (MNSD) government.

However, we found no evidence of prior arms dealings with the Nigerian government before 2014.

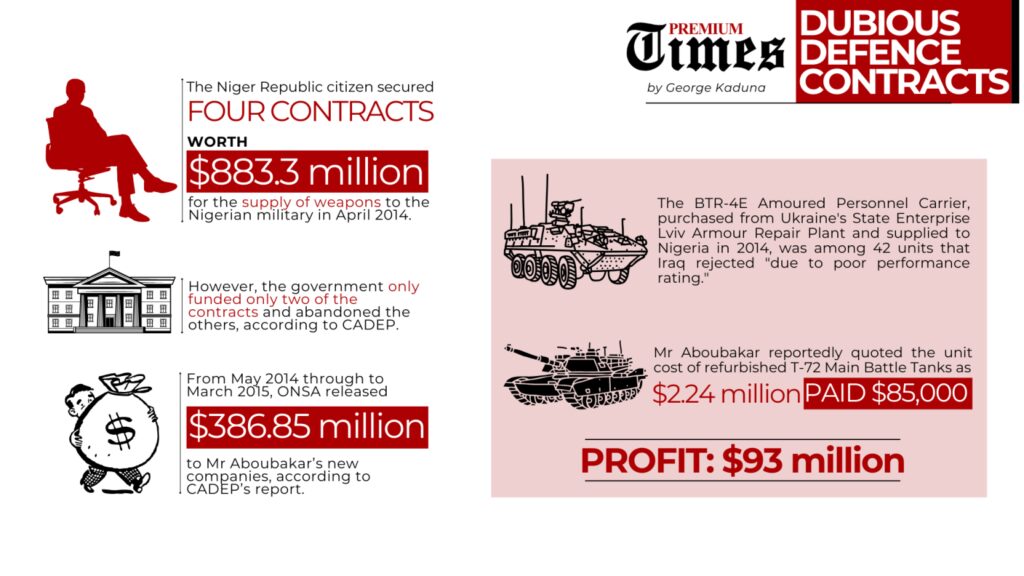

Mr Aboubakar secured four contracts worth $883.3 million to supply weapons to the Nigerian military in April 2014. However, only two contracts were funded.

CADEP documented flaws in the contracting processes, including inflated prices, undersupply of equipment, and the delivery of expired items prone to breakdown.

Additionally, some funds were transferred before the formalisation of contracts, with the Central Bank of Nigeria vaguely labelling the disbursements as “procurement of technical equipment.” This lack of specificity allowed Mr Aboubakar to allocate funds at his discretion without consultation with ONSA or the Nigerian Army, the panel stated.

The panel also found that some of the platforms and ammunition procured by Mr Aboubakar and deployed for the North-east operations “were aged or expired, lacked spares and prone to breakdown without immediate recovery equipment.”

The panel found that the army also failed to conduct mandatory pre-shipment inspections specified in the contracts, resulting in unreliable equipment that diminished operational capacity and led to more deaths. For instance, the BTR-4E Armoured Personnel Carrier purchased from Ukraine was among 42 units rejected by Iraq due to poor performance.

Complicating the matter, the panel said Mr Aboubakar involved companies with no contract agreement with the Nigerian authorities to supply some of the arms. “Consequently, it had been difficult for the ONSA, the Nigerian Army and SEI to reconcile the accounts vis-a-vis the equipment delivered.”

The committee recommended further investigations and potential prosecutions for Mr Aboubakar and other implicated defence contractors and military officials. A total of 18 military officers, including two former Chiefs of Army Staff, and numerous executives from companies linked to the shady contracts were identified for further investigations and possible prosecution.

Pay the price of flawed contracts

As a multitude of officials and contractors profited from the shadowy defence contracts amid Nigeria’s ongoing struggle against terrorism, the survivors of the devastation by Boko Haram and its factions in the last decade remain in perpetual grief over their losses – loved ones, ancestral homes, and livelihoods.

Hajara Muhammad, who is left with her daughter after fleeing Baga, one of the most traumatised communities in Borno State at the height of Boko Haram attacks in 2015, is a living memorial to the horror of the unrelenting insurgency of Boko Haram/ISWAP since at least 2010.

“I witnessed how Boko Haram slaughtered nine male members of my family,” Ms Muhammed recounted to PREMIUM TIMES in Hotoro in Tarauni Local Government Area of Kano State, where she has been forced to live as a displaced person after fleeing Baga in 2015.

Ms Muhammed is part of a growing number of about 3.3 million people already displaced due to conflicts and violence at the end of 2023, about half of them in Borno State, where she fled from in 2015.

Constructing the conduits

At 41 years old in April 2014, Mr Aboubakar was engaged by the Mr Dasuki-led Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) on behalf of the Nigerian government to supply arms to the Nigerian Army.

He swung into setting up corporate entities to execute the contracts.

He first set up the Societe D’Equipments Internationaux (SEI) Nigeria Limited, his flagship company in Nigeria, on 19 May 2014.

He allotted himself the majority shares of the company and designated himself the sole signatory to all the firm’s bank accounts.

Corporate documents reveal that the remaining shares were allotted to Ousmane Hima, who CADEP described as Mr Aboubakar’s brother, believed to be resident in Niamey, Niger.

Open-source records indicate that Mr Aboubakar established a lesser-known company, HKSK-SAWKI Ltd, on 5 June 2014. The company is named after Hong Kong-based HKSK-Sawki Limited, founded by Nigeriens Kabirou Abdoulkadri and Souleymane Siddo, who were residing in China. Initially registered as a furniture company in Hong Kong, HKSK-SAWKI Ltd became involved with Mr Aboubakar and SEI in controversial arms brokering activities, resulting in the US government seizing over $8.6 million intended for arms procurement for Nigeria in 2014.

On 9 June 2014, five days after setting up the Nigerian HKSK-Sawki, Mr Aboubakar set up APC Axiale Limited. He similarly has the controlling shares of the two new companies and is the sole signatory to their accounts.

We found 10 bank accounts in naira, dollars, euros and pounds sterling, linked to Mr Aboubakar. Four of these accounts were registered in SEI’s name. But he probably ran more than the accounts that we found.

With Mr Aboubakar as the sole signatory to all the companies’ corporate bank accounts, only an imaginary line separates his purse from that of his companies’ business ventures.

Establishing these companies and bank accounts, over which he exercised absolute control, effectively plugged his conduits to Nigeria’s defence cash cow.

The Aboubakar inflow

As stated earlier in this story, Mr Aboubakar was awarded four contracts worth $883.3 million to supply weapons to the Nigerian military in April 2014, but only two contracts were funded, according to CADEP.

The panel verified that, from May 2014 to March 2015, the Office of the National Security Adviser (ONSA) released $386.85 million to Mr Aboubakar’s companies.

We tracked only $295.15 million paid to Mr Aboubakar’s SEI not just by ONSA but by other government bodies. We also found a total sum of N350 million paid in two tranches by ONSA into SEI’s account.

It is likely that there were other accounts opened for SEI after its incorporation that we could not find or that EFCC did not file in court.

What is clear is that the two SEI dollar accounts we reviewed are at the heart of the company’s operations.

This is how the company received the funds from the Nigerian government.

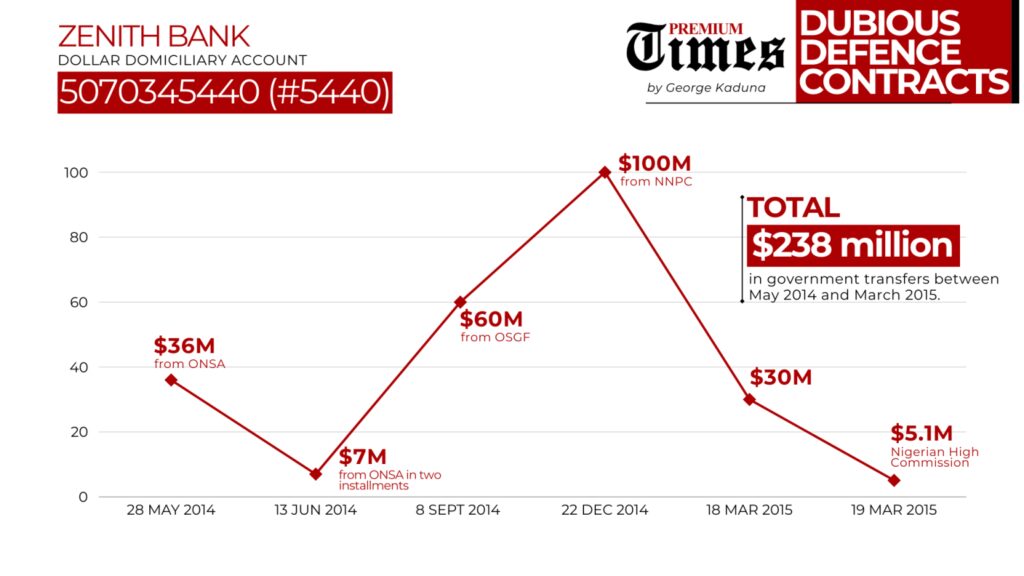

SEI’s Zenith Bank dollar domiciliary account 5070345440 (#5440) was opened on 21 May 2014, just two days after its incorporation. A week later, on 28 May 2014, it received its first major deposit of $36 million from ONSA. ONSA then transferred over $7 million in two instalments into the account on 13 June 2014.

After a three-month hiatus, the Office of the Secretary to the Government of the Federation deposited $60 million on 8 September 2014, followed by a $100 million transfer from NNPC on 22 December 2014.

The account received $30 million on 18 March 2015 and an additional $5.1 million from the “Nigerian High Commission” on 19 March, totalling over $238 million in government transfers between May 2014 and March 2015.

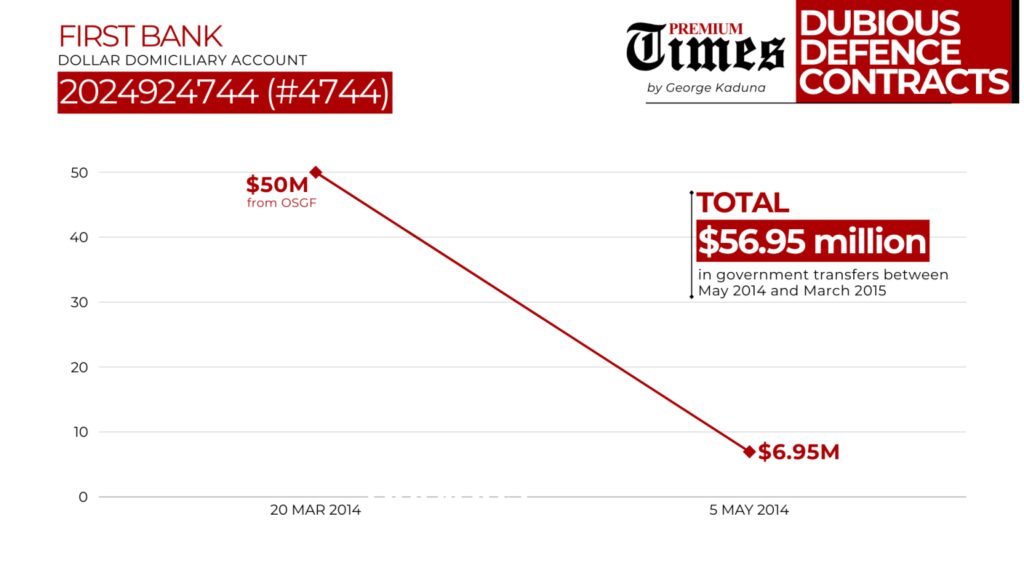

SEI also received funds through a First Bank dollar domiciliary account 2024924744 (#4744), opened with an initial balance of $2,000 on 21 May 2014. This account began receiving government funds in 2015, with a $50 million transfer from ONSA on 20 March and a final $6.95 million on 5 May, totalling $56.95 million.

In total, SEI received $295.15 million in government transfers between May 2014 and March 2015 to execute the defence contracts. Additionally, SEI’s naira account 1013860768 (#0768) at Zenith Bank received two transfers from ONSA, totalling N350 million.

“That a company received a huge amount of money from the government as contract payments without any serious organisational structure and the founder being the sole controller of its finances raise a serious red flag,” said Oluwaleke Atolagbe, a lawyer with vast experience prosecuting high-profile corruption cases, including procurement fraud and other financial crimes.

Mr Atolagbe, who is currently involved in prosecuting Mr Dasuki, said the lack of organisational structure should have raised the concerns about possible inflation of the contracts.

“Were those contracts executed? Did the award of those contracts follow due process? What patterns were used to withdraw or expend the money received? What was the money received expended on?” the lawyer asked further.

The hurry that characterised everything, from the award of the contracts to the setting up of the contracting companies and bank accounts for the firms overnight, and the Nigerian government’s payments to them, coupled with Mr Aboubakar’s absolute control over the firms’ finances, is a strong pointer to a possible lack of due diligence mandatory for all categories of contracts under the procurement law.

Heavy cash withdrawals, forex transfers by Hima Aboubakar

According to EFCC’s filings submitted to the Federal High Court in Abuja in May 2020, the funds wired by the Nigerian government’s bodies to SEI’s naira and dollar accounts were directly or indirectly the sources of funds with which Mr Aboubakar bought two properties – a house and a large expanse of undeveloped land, both in the heart of choice Maitama area of Abuja.

The commission insists that significant parts of the funds were “either withdrawn cash” by Mr Aboubakar “or transferred to BDC operators within Nigeria”.

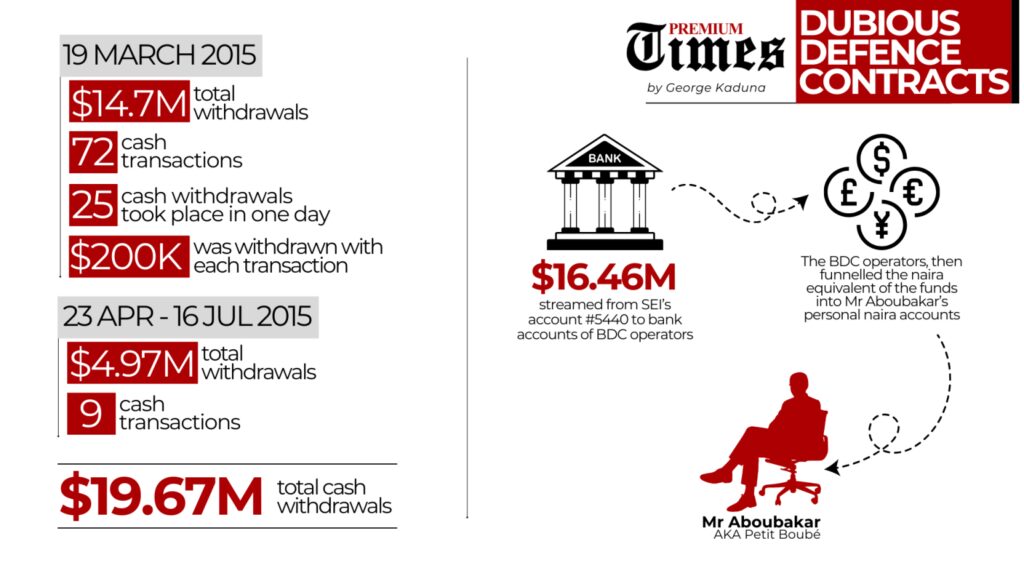

We tracked a total of $14.7 million withdrawn from the SEI’s Zenith Bank account #5440 in 72 cash transactions. Twenty-five of these cash withdrawals took place in just one day, 19 March 2015, with Mr Abubakar taking out $200,000 in each withdrawal.

Also, from 23 April 2015 to 16 July 2015, Mr Aboubakar made nine cash withdrawals totalling $4.97 million from SEI’s First Bank account #4744.

These sum up to $19.67 million in cash withdrawals believed to have been converted to naira. It suggested to investigators that the money could not have been used to import arms.

Our review tracked $16.46 million that streamed from SEI’s account #5440 to the bank accounts of BDC operators, who then funnelled the naira equivalent of the funds into Mr Aboubakar’s personal naira accounts – First Bank account 3083229135 (#9135) and Zenith Bank account #0143.

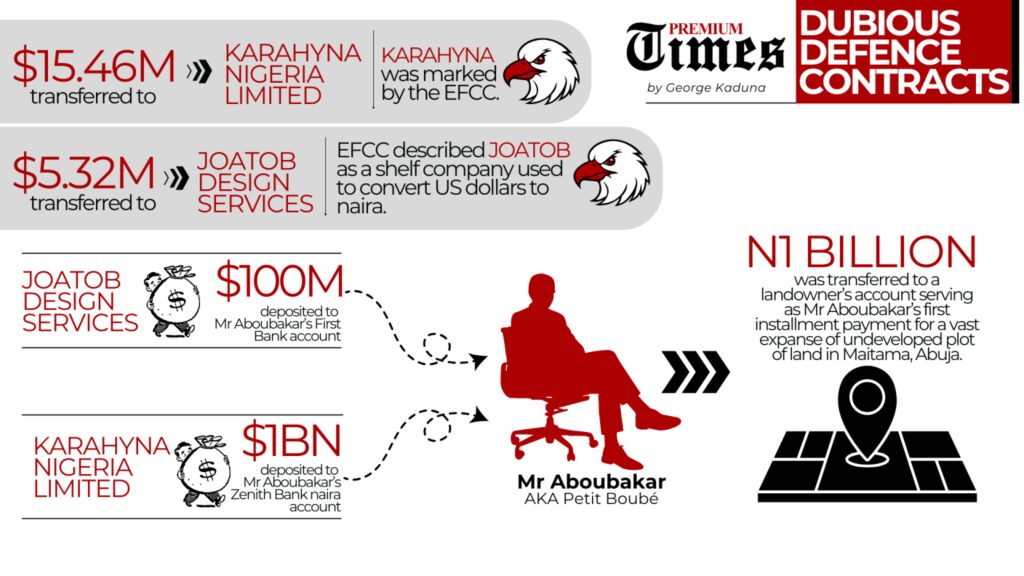

Of this amount, $15.46 million went to Karahyna Nigeria Limited, a firm marked by the EFCC as one of the major BDC operators allegedly used by Mr Aboubakar for converting the dollars received in SEI’s accounts to naira.

In 11 transactions between 23 April 2014 and 30 October 2015, a total of $5.32 million was transferred from SEI’s First Bank account #4744 to Joatob Design Services. EFCC described Joatab in a court filing as a shelf company used by a staff member of First Bank, Adetobi Olajumoke, to convert US dollars to naira.

The naira accounts of Mr Aboubakar and SEI reveal regular massive deposits from Karahyna and Joatob.

Joatob’s biggest single deposit was N100 million, which was transferred to Mr Aboubakar’s First Bank account 3083229135 (#9135) on 23 April 2015. That same day, Joatob earlier received $2 million from SEI’s Zenith Bank dollar account.

Karahyna’s biggest daily deposit was N1 billion, which it paid into Mr Aboubakar’s Zenith Bank Naira account #0143 in 10 tranches. The BDC wired the funds to Mr Aboubakar on 23 March 2015 after receiving its highest single transfer of $5 million from SEI’s Zenith Bank account #5440 earlier that day.

Immediately after the tenth tranche of N100 million hit account #0143 on 23 March, the entire N1 billion moved in one fell swoop to a landowner’s account, serving as Mr Aboubakar’s first instalment payment for a vast expanse of undeveloped land in Maitama, Abuja.

He also transferred N160 million from the same account as part payment for a N400 million house in Maitama.

A subsequent PREMIUM TIMES report will capture more details about the real estate and luxury car purchases.

‘Suspicious’

Mr Atolagbe, the private lawyer involved in prosecuting corruption cases for the EFCC (but not involved in Mr Aboubakar’s case), said heavy cash withdrawals and profuse use of forex operators by corporate organisations “are not necessarily criminal, but are suspicious”.

Just a piece of the jigsaw

West Africa’s GIABA, the body that monitors and promotes compliance with anti-money laundering and counter-terrorism financing measures in the region, warned Nigeria in its last mutual evaluation report issued in August 2021 about the implications of weak oversight over suspicious transactions and activities of BDCs in the country.

According to the body, “thousands of forex dealers operate informally and are entirely unsupervised,” supplying oxygen and enabling money laundering and terrorism financing to thrive.

It also identified a “limited scope of entities” that reported “suspicious transaction reports” and the quality of such reports as a major gap in the preventive measures with understated risk profiles. Many Designated Non-Financial Businesses and Professions (DNFBPs), including BDCs, generally do not file such suspicious transaction reports to the Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit (NFIU).

That is a colossal gap, the report said, in a nation where “the number of investigations, prosecutions and convictions for ML (money laundering) is inconsistent with the risk profile of the country.”

Mr Suraj, the HEDA chair, said the unchecked impunity in the land and insensitivity “has exacerbated the insecurity and criminality level across the country.”

Citizens like Ms Muhammed, displaced by Boko Haram attacks, pay the steep price for impunity that fuels insecurity in the country.

“We left Borno not because we love Kano but because we have no option but to flee our homes. Things have changed for the worse,” the woman, who lost nine family members – husband, children and father to Boko Haram attacks – told PREMIUM TIMES.