Ten years may sound like a blurry, distant future. But built into them are minutes, hours, days, weeks, months and years that provide harbor for infinitesimal opportunities that transform the lives of men and the fortunes of nations. Men and nations who benefit from time are those who employ their imagination in crafting long-term visions and discipline themselves to take little, vital steps leading to the realization of visions propounded by their imaginations.

Adhering to this time-tested reality, the administration of the late President Umaru Musa Yar’adua, in 2009, designed the famous Vision 2020. Wikipedia picked a quote from the lost website of the project, http://www.nv2020.org/, which describes the lost vision thus: “By 2020 Nigeria will be one of the 20 largest economies in the world, able to consolidate its leadership role in Africa and establish itself as a significant player in the global economic and political arena.”

A well-crafted document enunciating the vision, mission, strategies, and implementation of Vision 2020 project foregrounded the attempt by admitting that the country had abundant human and natural resources, enough to turn the vision into touchable reality. But this has not happened. The policy was the pride of the then Minister of National Planning, Shamsuddeen Usman, who sold it to Nigerians as sure steps to the country’s development. The following paragraphs explore how Nigeria failed to attain this feat in spite of the fact that it had all the potentials.

Becoming ‘one of the 20 largest economies in the world’

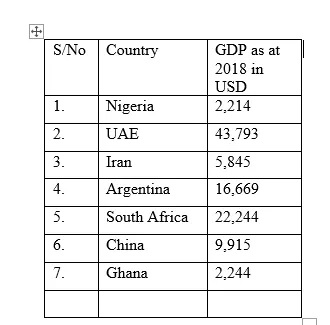

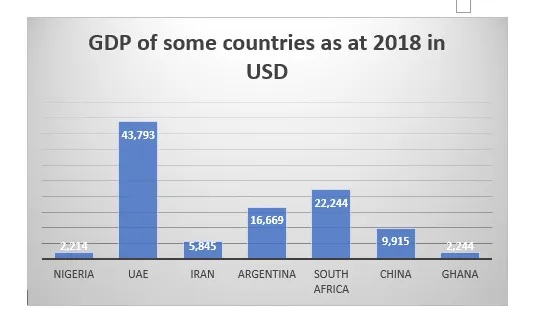

This nine-word statement may be considered as the catch-phrase of Vision 2020, as it elevates the mind with the hope that the country could leapfrog from poverty to join the ranks of the US, Britain, Sweden, Brazil, Turkey… and other developed countries in the world by Year 2020. As at 2009, Nigeria was among the 27 developing countries in the world, thanks to what the country earned from oil export. But the economy could not be powered by mere wishful thinking for it to leap across eight staircases, displace one of 20 and take a seat among developed countries. To become a developed society, a country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) must exceed $12,000. Nigeria’s GDP as at 2018, as stated on World Population Review platform, was $2,214. Features of a developed society include high level of industrialization; stability or control of birth and death rates through quality healthcare; more women working in high-ranking executive positions; and high debt rate (because of vibrant economy that makes it credit worthy). Nigeria lacks all these in Year 2020, when the country ought to have attained the status of ‘developed economy,’ if the country’s managers had exercised the discipline and put in place institutions to drive the vision on the path to success.

The table below shows Nigeria’s GDP compared to those countries chosen at random from among developing countries:

The target of Vision 2020, as quoted in the planning document was “to stimulate primary production to enhance the competitiveness of Nigeria’s real sector, as well as significantly increase production of processed and manufactured goods for export, stimulate domestic and foreign trade in value added goods and services and strengthen linkages among key sectors of the economy.” The steps to achieving this noble vision were beautifully laid out, but below are 10 areas in which the targeted objectives failed.

1.Promoting minerals and metals sector:

Among many planned programmes for the attainment of this objective was the completion of Ajaokuta Steel Company Limited and the Nigerian Iron Ore Mining Company by 2011. It was also envisaged that existing steel plants in the country would be expanded, which should have led to the addition of some five million tonnes of steel production in Nigeria. New steel plants were to be established, which should have taken off by 2019. The aggregate output of these plants should have enabled Nigeria to achieve a target of 12.2 million tonnes of steel by Year 2020. However, as at January 2020, Ajaokuta Steel is near-comatose, operating on skeletal basis, while most of its Russian well-trained staff in metallurgy and related minerals and metal production are retired or even dead. No existing steel plant has been expanded; no new steel plants have been set up. Over 95 percent of steel production in Nigeria today, according to the Ministry of Mines and Steel Development, is from scraps. The 43 steel plants in the country are operating far below capacity, and as at 2017, the ministry was dreaming of producing 1.2 million tonnes, as against 12.2 million tonnes promoted in Vision 2020.

2.Transforming Agriculture:

Under the vision, agriculture was expected to have been upgraded for subsistence farming to commercial farming which would enhance agricultural yields. It was canvassed that the Land Use Act of 1978 would be amended to enhance large scale investment for mechanized agricultural production. Also, value would be added to agricultural produce like tubers, cereals, oil palm, cocoa, citrus fruits, pineapples, so that farmers do not sell their produce to merchants at give-away prices. As at 2020, apart from rice production that has been enhanced due to the Central Bank of Nigeria’s Anchor Borrowers programme, not much has been done to add value to agricultural produce. The Land Use Act of 1978 has not been amended, while mechanized agriculture is not yet mainstream as most smallholder farmers are too poor to employ modern tools, such as tractors and plows, even with government support. Though the Buhari administration has claimed that Nigeria had achieved food sufficiency, the state of agriculture today is a far cry from the objectives of Vision 2020.

3.Developing Oil and Gas Sector:

For the oil and gas sector, Vision 2020 envisaged an increase in crude oil production and the refining capacity of Nigeria’s refineries to stimulate local value addition and to put the country in a position to meet domestic demand of refined products and export refined products. Gas production was expected to have been enhanced for domestic and industrial markets, while the Local Content Bill and Petroleum Industry Bill should have been passed into law to modern the oil and gas sector. As at January 2020, all these objectives are yet to be actualized as Nigeria, instead of refining products for local consumption and export, has remained a net importer of refined products. Though the Local Content Bill has been passed into law, the reform of the petroleum sector has been thwarted by forces in and outside government.

4.Exporting Processed and Manufactured Goods:

The well-crafted policy document envisaged that by Year 2020 Nigeria would become “a global hub in selected specialized products where Nigeria has competitive and absolute advantages.” Under this arrangement the country was expected to export processed and manufactured products, diversify its economy, expand employment opportunities and achieve the required growth rates for accomplishing Vision 2020. Instead of boosting the manufacturing sector, government policies over the years have led to the shrinking of the sector, low capacity utilization, relocation of some manufacturing firms from Nigeria to other climes, and the shut down of many. As a consequence, unemployment, instead of shrinking, has expanded to an all-time high rate, put at about 33 per cent of the country’s population. The diversification of the economy has remained a rhetoric, and the economic growth rate is too slow to energize development.

5.Developing Industrial Clusters:

Vision 2020 envisaged the creation of industrial clusters through Private Public Partnership (PPP) for the processing and manufacturing of goods for export markets. To meet this objective, government was supposed to have addressed industrial deficit in each zone in order to attract private sector investment. There were supposed to have been industrial parks and clusters, enterprise zones and incubation centres. This strategy has been employed in other countries and enhanced industrial development in Asian countries, but as at January 2020, it has not worked in Nigeria. There are pockets of industrial parks in the South-West, and a business incubation centre in Kano, but these are too insignificant to ignite the industrial activities envisaged in Vision 2020.

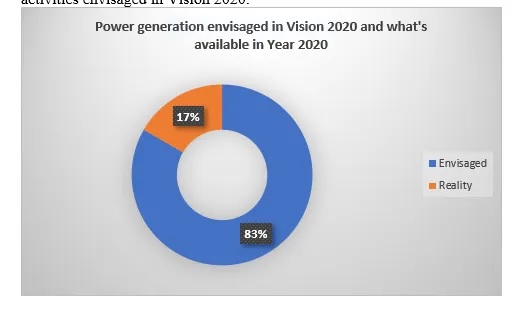

One of the major hindrances to industrial growth is the weak power sector. Vision 2020 document says by this year (2020) power generation and distribution should have hit 35,000 megawatts. In fact, between 2011 and 2020 IPPs should have increased power generation by 2000mw on an annual basis, while additional large hydro plants, coal-fired plants, IPPs and renewable power generation plants would have been completed to boost the sector. Most of these never happened. Power generation is still lingering at between 6,000mw and 7,000mw, about 20 per cent of the projected capacity.

6.Prioritizing Industrial Sub-Sector:

Going by the contents of Vision 2020, by this year 10 manufacturing industrial sub-sectors should have been developed in the short to medium term, to provide raw materials to downstream industries through the provision of local raw materials. In the document, high priority areas were identified, like chemical and pharmaceutical products, non-metallic minerals, basic metal, iron and steel, food beverages, tobaccos, textiles, wearing apparel, carpet, leather/leather footwear, etc. Many of these never happened, as Nigeria, instead of producing the items mentioned in the vision, has literally turned into a dumping ground for substandard quality of these products from China, and other Asian countries.

7.Enhancing Domestic and Foreign Trade in Value Added Products and Services:

This vision was to be achieved through diversification from primary products and increasing market share in new export markets; manufacturing, processing and export of valued added goods as the focal point of Nigeria’s trade strategy. In the document, products were categorized in a manner that showed that a lot of research and deep-thinking went into the exercise. However, as at 2020, Nigeria struggles to export primary products, as the envisaged value addition has not happened, primarily due to lack of government support for the private sector and high interest rate.

8.Promoting Export:

Going by the design of Vision 2020, the foreign policy focus of Nigeria ought to have shifted significantly by Year 2020. The designers of the document envisaged that ‘economic diplomacy’ would be the main theme of Nigeria’s foreign policy and the central point was the active promotion of ‘Made in Nigeria’ goods, through “nurturing strategic partnership with other countries.” Though ‘Made in Nigeria’ goods are exported to African countries, Nigeria’s share of the market is very low, as products from aggressive Chinese companies are taking over the continent. Unfortunately, it may be difficult to reverse this trend, as the country’s industrial base is too weak to compete with Chinese companies.

9.Administering the Borders:

The document projected that by Year 2020, there would be “48-hour turn around timing for clearing goods at the ports; complete electronic digitization and documentation of all trade documents through integrated ICT into all areas and processes needed to conduct free trade.” Today, goods clearance at Nigeria’s main port in Lagos is a nightmare, despite diverse government initiatives. Perhaps, the 48-hour target would be achieved when the rail project is completed, or when dry ports envisaged and the revival of other idle ports in the South-South and South East are achieved.

10.Promoting Domestic Trade:

Vision 2020 envisaged vibrant economic activities in the six geopolitical zones, such that each would specialize in the manufacture and processing of targeted value-added products to meet local demands. The North-East was to have been actively involved in processing minerals, ethanol, biodiesel, cotton, fruits, etc. The North-West would have been involved in meat processing, leather goods manufacturing, and biofuel manufacturing. North-Central – granite, furniture, cotton fabrics; South-East – counter drugs, leather goods, garments, and palm oil; South-West – plastics, garments, general goods; South-South – petrochemical (refined oil), fertilizer, plastics, oil servicing, etc. In order to boost these, there was supposed to have been in place integrated transported system on BOT and BOO basis. The network of rail, road, water and air should have been in place by now for the purposes of haulage and distribution of goods and services. Like the fate that befell the export policy, the domestic trade dream has been truncated by unbridled imports from China and other Asian countries where the cost goods production and delivery to Nigeria is far below the cost of manufacturing goods locally.

In the face of a failed Vision 2020, President Muhammadu Buhari’s administration claims to have a new vision framed as Economic Recovery Growth Plan (ERGP). The focus of this strategy is to diversify the economy, restore economic growth, create jobs, empower the youths, develop the human capital and infrastructure, improve business environment and bring about technological growth. These are similar to the objectives of Vision 2020, but without strong institutions and political will, the growth plan could collapse as well.